Natural History of Niles Canyon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Sediment / Unlock Alameda Creek

PUBLIC SEDIMENT / UNLOCK ALAMEDA CREEK WWW.RESILIENTBAYAREA.ORG ◄ BAYLANDS = LIVING INFRA STR CTY\, E' j(II( ........ • 400 +-' -L C Based on preliminary 0 analysis by SFfl. A more , detailed analysis is beinq E TIDAL MARSH conducted as part of -l/) the Healthy Watersheds l/) ro Resilient Aaylands E project (hwrb.sfei.org) +-' C QJ E "'O MUDFLAT QJ V1 SAC-SJ DELTA 0 1 Sediment supply was estimated by 'Sediment demand was estimated multiplying the current average using a mudflat soil bulK density of annual c;ediment load valuec; from 1.5 q c;ediment/rm c;oil (Brew and McKee et al. (in prep) by the number Williams :?010), a tidal marsh soil of years between 201 r and2100. bulK density ot 0.4 g sed1m ent / cm 3 c;oil (Callaway et al. :?010), and baywide mudflat and marsh area circa 2009 (BAARI vl). BAYLANDS TODAY BAYLANDS 2100 WITH 3' SLR LOW SEDIMENT SUPPLY BAYLANDS 2100 WITH 7' SLR LOW SEDIMENT SUPPLY WE MUST LOOK UPSTREAM TRIBUTARIES FEED THE BAY SONOMA CREEK NAPA RIVER PETALUMA CREEK WALNUT CREEK ALAMEDA CREEK COYOTE CREEK GUADALUPE CREEK ALAMEDA CREEK SEDIMENTSHED ALAMEDA CREEK ALAMEDA CREEK WATERSHED - 660 SQMI OAKLAND ALAMEDA CREEK WATERSHED SAN FRANCISCO SAN JOSE THE CREEK BUILT AN ALLUVIAL FAN AND FED THE BAY ALAMEDA CREEK SOUTH BAY NILES CONE ALLUVIAL FAN HIGH SEDIMENT FEEDS MARSHES TIDAL WETLANDS IT HAS BEEN LOCKED IN PLACE OVER TIME LIVERMORE PLEASANTON SUNOL UNION CITY NILES SAN MATEO BRIDGE EDEN LANDING FREMONT NEWARK LOW SEDIMENT CARGILL SALT PONDS DUMBARTON BRIDGE SEDIMENT FLOWS ARE HIGHLY MODIFIED SEDIMENT IS STUCK IN CHANNEL IMPOUNDED BY DAMS UPSTREAM REDUCED SUPPLY TO THE BAY AND VULNERABILITIES ARE EXACERBATED BY CLIMATE CHANGE EROSION SUBSIDENCE SEA LEVEL RISE THE FLOOD CONTROL CHANNEL SAN MATEO BRIDGE UNION CITY NILES RUBBER DAMS BART WEIR EDEN LANDING PONDS HEAD OF TIDE FREMONT 880 NEWARK TIDAL EXTENT FLUVIAL EXTENT DUMBARTON BRIDGE. -

Hayward Regional Shoreline Adaptation Master Plan Appendix a Stakeholder and Public Comments

SCAPE ARCADIS CONVEY RE:FOCUS SFEI HAYWARD REGIONAL SHORELINE ADAPTATION MASTER PLAN FOR THE HAYWARD AREA SHORELINE PLANNING AGENCY (HASPA) PART OF A JOINT POWERS AGREEMENT OF THE CITY OF HAYWARD, HAYWARD AREA RECREATION AND PARK DISTRICT, AND EAST BAY REGIONAL PARK DISTRICT HAYWARD REGIONAL SHORELINE MASTER PLAN APPENDIX A STAKEHOLDER AND PUBLIC COMMENTS SUBMITTED 10/02/2020 PUBLIC ONLINE SURVEY 02/27/19 - 03/15/19 ONLINE SURVEY SUMMARY A 23-question survey was conducted on behalf of the Hayward Area Shoreline Planning Agency (HASPA) to assess the public’s general understanding of Hayward Regional Shoreline, mainly in regard to sea level rise, potential flooding, and participants’ feelings, concerns, and predictions regarding these issues. In the spring of 2019, this survey was completed by approximately 900 people throughout the Bay Area, primarily those who live, work, commute through, or recreate at or near the shoreline. 1. Are you familiar with the Hayward Regional Shoreline that is managed by East Bay Regional Park District and Hayward Area Recreation and Park District? The majority of people surveyed are familiar with the Hayward Regional Shoreline. 2. What’s your association with the project area? The majority of those surveyed either drive through the area or enjoy the views of the Shoreline. Approximately two thirds of those surveyed visit the Shoreline and about one third live near the Shoreline. A smaller percentage (about ten percent) specified that they enjoy activities such as birding, cycling, jogging or walking along the Shoreline. A negligible amount of those surveyed stated they’d like to see restaurants built on the area. -

Active Wetland Habitat Projects of the San

ACTIVE WETLAND HABITAT PROJECTS OF THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY JOINT VENTURE The SFBJV tracks and facilitates habitat protection, restoration, and enhancement projects throughout the nine Bay Area Projects listed Alphabetically by County counties. This map shows where a variety of active wetland habitat projects with identified funding needs are currently ALAMEDA COUNTY MAP ACRES FUND. NEED MARIN COUNTY (continued) MAP ACRES FUND. NEED underway. For a more comprehensive list of all the projects we track, visit: www.sfbayjv.org/projects.php Alameda Creek Fisheries Restoration 1 NA $12,000,000 McInnis Marsh Habitat Restoration 33 180 $17,500,000 Alameda Point Restoration 2 660 TBD Novato Deer Island Tidal Wetlands Restoration 34 194 $7,000,000 Coyote Hills Regional Park - Restoration and Public Prey enhancement for sea ducks - a novel approach 3 306 $12,000,000 35 3.8 $300,000 Access Project to subtidal habitat restoration Hayward Shoreline Habitat Restoration 4 324 $5,000,000 Redwood Creek Restoration at Muir Beach, Phase 5 36 46 $8,200,000 Hoffman Marsh Restoration Project - McLaughlin 5 40 $2,500,000 Spinnaker Marsh Restoration 37 17 $3,000,000 Eastshore State Park Intertidal Habitat Improvement Project - McLaughlin 6 4 $1,000,000 Tennessee Valley Wetlands Restoration 38 5 $600,000 Eastshore State Park Martin Luther King Jr. Regional Shoreline - Water 7 200 $3,000,000 Tiscornia Marsh Restoration 39 16 $1,500,000 Quality Project Oakland Gateway Shoreline - Restoration and 8 200 $12,000,000 Tomales Dunes Wetlands 40 2 $0 Public Access Project Off-shore Bird Habitat Project - McLaughlin 9 1 $1,500,000 NAPA COUNTY MAP ACRES FUND. -

Historical Status of Coho Salmon in Streams of the Urbanized San Francisco Estuary, California

CALIFORNIA FISH AND GAME California Fish and Game 91(4):219-254 2005 HISTORICAL STATUS OF COHO SALMON IN STREAMS OF THE URBANIZED SAN FRANCISCO ESTUARY, CALIFORNIA ROBERT A. LEIDY1 U. S. Environmental Protection Agency 75 Hawthorne Street San Francisco, CA 94105 [email protected] and GORDON BECKER Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration 4179 Piedmont Avenue, Suite 325 Oakland, CA 94611 [email protected] and BRETT N. HARVEY Graduate Group in Ecology University of California Davis, CA 95616 1Corresponding author ABSTRACT The historical status of coho salmon, Oncorhynchus kisutch, was assessed in 65 watersheds surrounding the San Francisco Estuary, California. We reviewed published literature, unpublished reports, field notes, and specimens housed at museum and university collections and public agency files. In watersheds for which we found historical information for the occurrence of coho salmon, we developed a matrix of five environmental indicators to assess the probability that a stream supported habitat suitable for coho salmon. We found evidence that at least 4 of 65 Estuary watersheds (6%) historically supported coho salmon. A minimum of an additional 11 watersheds (17%) may also have supported coho salmon, but evidence is inconclusive. Coho salmon were last documented from an Estuary stream in the early-to-mid 1980s. Although broadly distributed, the environmental characteristics of streams known historically to contain coho salmon shared several characteristics. In the Estuary, coho salmon typically were members of three-to-six species assemblages of native fishes, including Pacific lamprey, Lampetra tridentata, steelhead, Oncorhynchus mykiss, California roach, Lavinia symmetricus, juvenile Sacramento sucker, Catostomus occidentalis, threespine stickleback, Gasterosteus aculeatus, riffle sculpin, Cottus gulosus, prickly sculpin, Cottus asper, and/or tidewater goby, Eucyclogobius newberryi. -

(Oncorhynchus Mykiss) in Streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California

Historical Distribution and Current Status of Steelhead/Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in Streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California Robert A. Leidy, Environmental Protection Agency, San Francisco, CA Gordon S. Becker, Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration, Oakland, CA Brett N. Harvey, John Muir Institute of the Environment, University of California, Davis, CA This report should be cited as: Leidy, R.A., G.S. Becker, B.N. Harvey. 2005. Historical distribution and current status of steelhead/rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California. Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration, Oakland, CA. Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration TABLE OF CONTENTS Forward p. 3 Introduction p. 5 Methods p. 7 Determining Historical Distribution and Current Status; Information Presented in the Report; Table Headings and Terms Defined; Mapping Methods Contra Costa County p. 13 Marsh Creek Watershed; Mt. Diablo Creek Watershed; Walnut Creek Watershed; Rodeo Creek Watershed; Refugio Creek Watershed; Pinole Creek Watershed; Garrity Creek Watershed; San Pablo Creek Watershed; Wildcat Creek Watershed; Cerrito Creek Watershed Contra Costa County Maps: Historical Status, Current Status p. 39 Alameda County p. 45 Codornices Creek Watershed; Strawberry Creek Watershed; Temescal Creek Watershed; Glen Echo Creek Watershed; Sausal Creek Watershed; Peralta Creek Watershed; Lion Creek Watershed; Arroyo Viejo Watershed; San Leandro Creek Watershed; San Lorenzo Creek Watershed; Alameda Creek Watershed; Laguna Creek (Arroyo de la Laguna) Watershed Alameda County Maps: Historical Status, Current Status p. 91 Santa Clara County p. 97 Coyote Creek Watershed; Guadalupe River Watershed; San Tomas Aquino Creek/Saratoga Creek Watershed; Calabazas Creek Watershed; Stevens Creek Watershed; Permanente Creek Watershed; Adobe Creek Watershed; Matadero Creek/Barron Creek Watershed Santa Clara County Maps: Historical Status, Current Status p. -

Salmon and Steelhead in Your Creek: Restoration and Management of Anadromous Fish in Bay Area Watersheds

Salmon and Steelhead in Your Creek: Restoration and Management of Anadromous Fish in Bay Area Watersheds Presentation Summaries (in order of appearance) Gary Stern, National Marine Fisheries Service Steelhead as Threatened Species: The Status of the Central Coast Evolutionarily Significant Unit Under the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA), a "species" is defined to include "any distinct population segment of any species of vertebrate fish or wildlife which interbreeds when mature." To assist NMFS apply this definition of "species to Pacific salmon stocks, an interim policy established the use of "evolutionarily significant unit (ESU) of the biological species. A population must satisfy two criteria to be considered an ESU: (1) it must be reproductively isolated from other conspecific population units; and (2) it must represent an important component in the evolutionary legacy of the biological species. The listing of steelhead as "threatened" in the California Central Coast resulted from a petition filed in February 1994. In response to the petition, NMFS conducted a West Coast-wide status review to identify all steelhead ESU’s in Washington, Oregon, Idaho and California. There were two tiers to the review: (1) regional expertise was used to determine the status of all streams with regard to steelhead; and (2) a biological review team was assembled to review the regional team's data. Evidence used in this process included data on precipitation, annual hydrographs, monthly peak flows, water temperatures, native freshwater fauna, major vegetation types, ocean upwelling, and smolt and adult out-migration (i.e., size, age and time of migration). Steelhead within San Francisco Bay tributaries are included in the Central California Coast ESU. -

SFEI Introductory Brochure on Alameda Creek Historical Ecology Study

THE HISTORICAL ECOLOGY OF 1878 ALAMEDA CREEK PROJECT OVERVIEW Over the next two years, a team of researchers will collect and synthesize thousands of historical documents relating to the past landscape of the Alameda Creek watershed. This process will reveal what the watershed looked like and how it functioned before extensive development. This information will help local stakeholders to better understand the causes of present-day challenges and to develop strategies for watershed enhancement. 1939 PROJECT GOALS The Alameda Creek Historical Ecology Study aims to develop an understanding of the historical extent and function of terrestrial, fluvial, riparian, and wetland resources in the Alameda Creek watershed. Examples of topics addressed in the project include: • What kinds of wetlands occurred where (and why)? • How did riparian vegetation, seasonal flow, and fish habitat vary among different stream reaches? • How have creek depth, width, morphology, and connectivity changed over time? • What habitats characterized adjacent floodplains: for example, oak savanna, wildflower meadows, or seasonal wetlands? 2005 AMADOR HAYWARD VALLEY LIVERMORE VALLEY NILES Alameda NILES SAN CONE Creek CANYON ANTONIO SUNOL RESERVOIR VALLEY Alameda Creek CALAVERAS Lower Alameda Creek at Quarry Lakes viewed through RESERVOIR time in a 1878 map (Thompson & West), 1939 aerial photos Flood view of Mocho Canal in January 1914 (USDA), and 2005 aerial photos. (USDA NAIP) The geographic focus is the floodplains, from the Pleasanton-Santa Rita county road. (SFPUC archives) valleys, and alluvial plains adjacent to Alameda Creek and its tributaries. This includes the Livermore and Amador valleys, Sunol Valley and Niles Canyon, and the Niles cone and adjoining baylands. -

2021 Invasive Spartina Project Treatment Schedule

2021 Invasive Spartina Project Treatment Schedule Updated: 7/26/21 Environmental Review Site Locations (map) Treatment Methods Where: How: Herbicide Use: of Imazapyr Treatment Method Treatment Location Treatment Dates* Imazapyr Herbicide Manual Digging, Site Sub-Area *(COI=Dug during Complete Amphibious Aerial: Mowing, Site Name Sub-Area Name Truck Backpack Airboat # Number course of inventory) for 2021? vehicle Broadcast and/or Covering 01a Channel Mouth X Lower Channel (not including 01b X mouth) 01c Upper Channel X Alameda Flood 4 years with no 1 Upper Channel - Union City Blvd to Control Channel 01d invasive Spartina I-880 (2017-2020) 01e Strip Marsh No. of Channel Mouth X No Invasive 01f Pond 3-AFCC Spartina 2020 02a.1a Belmont Slough Mouth X X X 02a.1b Belmont Slough Mouth South X X X Upper Belmont Slough and 02a.2 X X X Redwood Shores 02a.3 Bird Island X 02a.4 Redwood Shores Mitigation Bank X 02b.1 Corkscrew Slough X X Steinberger Slough South, 02b.2 X X Redwood Creek Northwest 02c.1a B2 North Quadrant West 8/14 X X 02c.1b B2 North Quadrant East 8/24 X X 02c.2 B2 North Quadrant South 8/12-8/13 X X 02d.1a B2 South Quadrant West X 02d.1b B2 South Quadrant East X 02d.2 B2 South Quadrant (2) X 2 Bair/Greco Islands 02d.3 B2 South Quadrant (3) X 02e Westpoint Slough NW X X 02f Greco Island North X X 02g Westpoint Slough SW and East X X 02h Greco Island South X X 02i Ravenswood Slough & Mouth X Ravenswood Open Space Preserve 02j.1 X (north Hwy 84) * Scheduling occurs throughout the treatment season. -

Up Your Creek! the Electronic Newsletter of the Alameda Creek Alliance

Up Your Creek! The electronic newsletter of the Alameda Creek Alliance Alameda Creek Restoration Day – March 17 Join the Alameda Creek Alliance for a stewardship project along Alameda Creek on Saturday, March 17th from 10 am to 1 pm. Come spend a Saturday morning enhancing habitat along the creek with friends and neighbors. We’ll continue our project of removing ivy and clearing weeds around our recent native tree and shrub plantings. We’ll also work on clearing a pile of tree trimmings that had been dumped at our site. This continues past work by ACA volunteers, and your efforts are enhancing habitat for fish and wildlife along Alameda Creek now and for years to come. Thanks to Linda, a CivicSpark Fellow at Alameda County Water District, for partnering with us on this workday. For more details and to register please visit our Eventbrite page. We ask that you register in advance on there so we know how many people to expect, but last-minute volunteers are always welcome. There’s no need to print the registration ticket. Meet at 10 am near 1004 Old Canyon Road in Fremont (just past Clarke Drive). There is parking along the road on the creek side where it widens some. We'll work until 1:00 pm. Please wear long pants and sturdy, closed-toe shoes that can get dirty (no sandals or flip-flops). We provide gloves and tools. The work isn't on much of a slope, but the ground can be uneven. The ground and vegetation will likely be cool and wet when we start, so please wear clothes that can get damp and possibly dirty. -

Gentry Suisun Draft EIR Vol II

Gentry/Suisun Annexation Traffic Impact Study February 2006 APPENDIX A- EXISTING TRAFFIC COUNTS 162 Gentry/Suisun Annexation Traffic Impact Study February 2006 APPENDIX B- EXISTING LOS RESULTS 163 Gentry/Suisun Annexation Traffic Impact Study February 2006 APPENDIX C- EXISTING PLUS APPROVED LOS RESULTS 164 Gentry/Suisun Annexation Traffic Impact Study February 2006 APPENDIX D- MODEL DOCUMENTATION 165 Gentry/Suisun Annexation Traffic Impact Study February 2006 APPENDIX E- CUMULATIVE LOS RESULTS 166 Administrative Draft EIR Suisun Gentry Project February 10, 2006 4.8 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES INTRODUCTION This section of the Environmental Impact Report (EIR) evaluates potential biological resource impacts associated with the implementation of the Proposed Suisun Gentry Project and includes a discussion of the mitigation measures necessary to reduce impacts to a less-than-significant level where possible. The information contained in this analysis is primarily based upon the Biological Assessment, Gentry-Suisun Project, City of Suisun City, Solano County, California prepared by The Huffman-Broadway Group (2006) and the Wetland Delineation and Special- Status Species Survey Report prepared by Vollmar Consulting (2003). Additional details on plant and wildlife species presence are based upon field surveys performed by Foothill Associates’ biologists. This report describes the habitat types, jurisdictional waters, and presence/absence of special-status plants and animals at the Proposed Project area and provides a review of existing literature, maps, and aerial photography pertaining to the biological resources of the area. It also evaluates potential impacts of the proposed Project in relation to CEQA and other environmental laws, and provides mitigation recommendations. Foothill Associates has prepared this Section of the EIR for the proposed Suisun Gentry Project (Project) in central Solano County, California. -

Up Your Creek! the Electronic Newsletter of the Alameda Creek Alliance

Up Your Creek! The electronic newsletter of the Alameda Creek Alliance Membership Renewal Request Please support your local creek group by becoming a member of the Alameda Creek Alliance or renewing your membership. If you have already donated or renewed, thank you very much for your support! Download an ACA membership form or make a donation via PayPal here. Your membership allows us to continue to be an effective voice for creek restoration and for the protection of native species and their habitats in the Alameda Creek watershed. The Alameda Creek Alliance is a non-profit organization and donations are tax-deductible. Spring Alameda Creek Events Alameda Creek Cleanup – January 20 MLK Day of Service on Alameda Creek – Monday, January 20, from 10 am to 12:30 pm. Join us at our newly adopted stretch of Alameda Creek just upstream from the Niles Staging Area, where we'll clean trash from the creek and remove ivy invading some of the large mature trees at the site. Our work will vary from easy to straining based on individual interests and abilities. We'll provide gloves, tools, water and snacks. Wear long pants, a long-sleeve shirt, and shoes with good traction, as the ground can be uneven. Meet at the parking lot for the Niles Staging Area of the Alameda Creek Trail, near Mission Blvd. and Niles Canyon Road, off Old Canyon Road in Fremont. If you arrive late, follow the path upstream past the picnic area to find us. RSVP to Ralph Boniello, [email protected] Sunol Bio Blitz – March 8 Join us for our first Bio Blitz in the Alameda Creek watershed. -

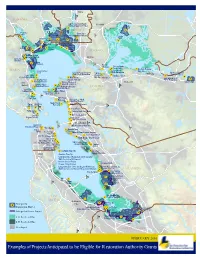

Examples of Projects Anticipated to Be Eligible for Restoration Authority Grants

Napa 221 |þ C a c h SONOMA e S lo u g Edgerly Island and South Fairfield h Wetlands Opportunity Area Rush Ranch NAPA Petaluma Lower Napa Marsh Skaggs Island Napa-Sonoma River Wetlands 80 Restoration ¨¦§ Suisun Lower Sonoma Marshes Marsh Creek Tolay Creek Strip Marsh Watershed Sears Point |þ37 Enhancements Bahia Tolay Creek Cullinan Wetlands Lagoon Ranch Lower Petaluma SOLANO er River iv R o Simmons Slough t r en e v m i Seasonal Wetlands Vallejo ra Novato Creek ac R S n i Baylands u q Bel Marin a o Keys Wetlands 780 J § Benicia n ¨¦ a Shoreline Pacheco Marsh S Restoration N Bay Point Regional e MARIN Lower Walnut w Y Lower Gallinas Shoreline ork Slou Creek Chelsea Wetlands & Lower Martinez Creek Restoration gh Big Break Regional Pinole Creek Restoration Pittsburg Shoreline-Oakley Lower Miller Regional McNabney Marsh Shoreline Creek/McInnis Marsh Point Pinole Martinez East Antioch Creek Creek to Bay Trash Regional Shoreline Marsh Restoration San Reduction Projects Breuner Marsh and Concord Dutch Slough Lower Rheem Creek Rafael Tiscornia Marsh 242 Restoration Project North Richmond Shoreline CONTRA |þ - San Pablo Marsh Lower Corte COSTA Madera Creek Point Molate, Lower Wildcat Richmond Creek Madera ¨¦§580 Bay Park Miller-Knoz, Richmond Western Stege Marsh Restoration Program Brooks Island Bothin Aramburu Point Isabel, Richmond Richmond 24 Marsh Island131 |þ |þ Albany Beach Richardson Berkeley North Strip Basin Bay Sausalito Berkeley Brickyard Eelgrass Preserve Point Emery Emeryville Crescent Oakland |þ13 Crissy Field Oakland Gateway Shoreline Educational Programs ¨¦§80 China Basin 680 Tennessee Alameda Point ¨¦§ Hollow Pier 70 - Crane Alameda Point Seaplane Lagoon Cove Park Lower Sausal Creek Pier 70 - Slipways Park Crown Beach – Neptune Point Islais Creek Warm Water Cove Park Pier 94- Wetlands Enhancement Martin Luther King Jr.