Sandifer-Smith George

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SF COMMENTARY 81 40Th Anniversary Edition, Part 2

SF COMMENTARY 81 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 2 June 2011 IN THIS ISSUE: THE COLIN STEELE SPECIAL COLIN STEELE REVIEWS THE FIELD OTHER CONTRIBUTORS: DITMAR (DICK JENSSEN) THE EDITOR PAUL ANDERSON LENNY BAILES DOUG BARBOUR WM BREIDING DAMIEN BRODERICK NED BROOKS HARRY BUERKETT STEPHEN CAMPBELL CY CHAUVIN BRAD FOSTER LEIGH EDMONDS TERRY GREEN JEFF HAMILL STEVE JEFFERY JERRY KAUFMAN PETER KERANS DAVID LAKE PATRICK MCGUIRE MURRAY MOORE JOSEPH NICHOLAS LLOYD PENNEY YVONNE ROUSSEAU GUY SALVIDGE STEVE SNEYD SUE THOMASON GEORGE ZEBROWSKI and many others SF COMMENTARY 81 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 2 CONTENTS 3 THIS ISSUE’S COVER 66 PINLIGHTERS Binary exploration Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) Stephen Campbell Damien Broderick 5 EDITORIAL Leigh Edmonds I must be talking to my friends Patrick McGuire The Editor Peter Kerans Jerry Kaufman 7 THE COLIN STEELE EDITION Jeff Hamill Harry Buerkett Yvonne Rousseau 7 IN HONOUR OF SIR TERRY Steve Jeffery PRATCHETT Steve Sneyd Lloyd Penney 7 Terry Pratchett: A (disc) world of Cy Chauvin collecting Lenny Bailes Colin Steele Guy Salvidge Terry Green 12 Sir Terry at the Sydney Opera House, Brad Foster 2011 Sue Thomason Colin Steele Paul Anderson Wm Breiding 13 Colin Steele reviews some recent Doug Barbour Pratchett publications George Zebrowski Joseph Nicholas David Lake 16 THE FIELD Ned Brooks Colin Steele Murray Moore Includes: 16 Reference and non-fiction 81 Terry Green reviews A Scanner Darkly 21 Science fiction 40 Horror, dark fantasy, and gothic 51 Fantasy 60 Ghost stories 63 Alternative history 2 SF COMMENTARY No. 81, June 2011, 88 pages, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia. -

12/2008 Mechanical, Photocopying, Recording Without Prior Written Permission of Ukchartsplus

All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, stored in Issue 383 a retrieval system, posted on an Internet/Intranet web site, forwarded by email, or otherwise transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, 27/12/2008 mechanical, photocopying, recording without prior written permission of UKChartsPlus Symbols: Platinum (600,000) Number 1 Gold (400,000) Silver (200,000) 12” Vinyl only 7” Vinyl only Download only Pre-Release For the week ending 27 December 2008 TW LW 2W Title - Artist Label (Cat. No.) High Wks 1 NEW HALLELUJAH - Alexandra Burke Syco (88697446252) 1 1 1 1 2 30 43 HALLELUJAH - Jeff Buckley Columbia/Legacy (88697098847) -- -- 2 26 3 1 1 RUN - Leona Lewis Syco ( GBHMU0800023) -- -- 12 3 4 9 6 IF I WERE A BOY - Beyoncé Columbia (88697401522) 16 -- 1 7 5 NEW ONCE UPON A CHRISTMAS SONG - Geraldine Polydor (1793980) 2 2 5 1 6 18 31 BROKEN STRINGS - James Morrison featuring Nelly Furtado Polydor (1792152) 29 -- 6 7 7 2 10 USE SOMEBODY - Kings Of Leon Hand Me Down (8869741218) 24 -- 2 13 8 60 53 LISTEN - Beyoncé Columbia (88697059602) -- -- 8 17 9 5 2 GREATEST DAY - Take That Polydor (1787445) 14 13 1 4 10 4 3 WOMANIZER - Britney Spears Jive (88697409422) 13 -- 3 7 11 7 5 HUMAN - The Killers Vertigo ( 1789799) 50 -- 3 6 12 13 19 FAIRYTALE OF NEW YORK - The Pogues featuring Kirsty MacColl Warner Bros (WEA400CD) 17 -- 3 42 13 3 -- LITTLE DRUMMER BOY / PEACE ON EARTH - BandAged : Sir Terry Wogan & Aled Jones Warner Bros (2564692006) 4 6 3 2 14 8 4 HOT N COLD - Katy Perry Virgin (VSCDT1980) 34 -- -

Download Festival 2009 Timetable

Download Festival 2009 Timetable Friday Saturday Sunday Main 2nd Tuborg Red Bull Main 2nd Tuborg Red Bull Main 2nd Tuborg Red Bull 11:00 11:00 11:00 11:05 11:05 Auger 11:05 Stone Sacred Mother Fall From 11:10 11:10 Ripper Acid Drop 11:10 Brides 11:15 11:15 The Crave Bane 11:15 Gods Tounge Grace 11:20 11:20 Owens 11:20 11:25 11:25 11:25 11:30 11:30 11:30 11:35 11:35 11:35 11:40 11:40 11:40 11:45 11:45 11:45 Trigger 11:50 11:50 No 11:50 Violent 11:55 11:55 Five Symphony Japanese 11:55 Tesla The Raucous 12:00 12:00 Americana 12:00 Soho 12:05 12:05 Finger Voyeurs 12:05 Bloodshed Jays 12:10 12:10 Cult 12:10 12:15 12:15 Death 12:15 12:20 12:20 12:20 12:25 12:25 Punch 12:25 12:30 12:30 12:30 12:35 12:35 12:35 Suicide 12:40 12:40 Black 12:40 Turbowolf 12:45 12:45 The 12:45 Million Dollar 12:50 12:50 Hardcore 12:50 Skin Silence 12:55 12:55 Spiders Computers 12:55 Reload 13:00 13:00 Superstar 13:00 13:05 The 13:05 Devil 13:05 Hollywood Sleepercurve 13:10 Steadlür Instigators 13:10 13:10 13:15 Undead 13:15 Driver 13:15 13:20 13:20 13:20 Pulled Apart 13:25 13:25 13:25 God 13:30 13:30 13:30 Black By Horses 13:35 13:35 Facecage 13:35 Forbid 13:40 Hunting The 13:40 In Case 13:40 13:45 13:45 Serpico 13:45 Stone Jettblack 13:50 In This Minotaur 13:50 Of Fire 13:50 Cherry 13:55 The Tripswitch 13:55 13:55 14:00 Moment 14:00 14:00 14:05 14:05 14:05 14:10 Blackout 14:10 14:10 Esoterica 14:15 14:15 Hatebreed 14:15 14:20 14:20 14:20 Sevendust 14:25 Bleed From 14:25 Loverman 14:25 14:30 A Day 14:30 14:30 14:35 Within 14:35 Forever 14:35 Fei 14:40 To Young 14:40 -

THE UNIVERSITY of READING the Development of Memory for Actions

THE UNIVERSITY OF READING The Development of Memory for Actions Jamie Drew Mackay A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Psychology Harry Pitt Building University of Reading Earley Gate Reading RG6 6AL June 2005 2 “The suggested intention slumbers on in the person concerned until the time for its execution approaches. Then it awakes and impels him to perform the action.” Sigmund Freud (1991) Psychopathology of Everyday Life 3 Declaration of Original Authorship ‘I confirm that this is my own work and the use of all material from other sources has been properly and fully acknowledged.’ Signature. 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Although perhaps this thesis has been a long time coming, I could not have reached this point without some help. I would like to take this opportunity to acknowledge this help (in no particular order!). To Judi and Jayne, I would like to thank you for your time, energy and enthusiasm. From an academic perspective, you were my motivation and drive, full to the brim with advice and encouragement. To Paul Heaton for all the programming and the odd chat about web technologies! To Mum and Dad: Thank you for your love and emotional support. Oh and the odd rent cheque! I might not say it often enough, but I do love you both very much. To Lou, although a recent addition to my life, you have become a significant addition. You have given so much more meaning to my life. Thank you for your love, cuddles and text messages of support! I would also like to acknowledge all of my friends: Those in Reading, those who have since moved away from Reading and those further a field. -

Előadó Album Címe a Balladeer Panama -Jewelcase- a Balladeer Where Are You, Bambi

Előadó Album címe A Balladeer Panama -Jewelcase- A Balladeer Where Are You, Bambi.. A Fine Frenzy Bomb In a Birdcage A Flock of Seagulls Best of -12tr- A Flock of Seagulls Playlist-Very Best of A Silent Express Now! A Tribe Called Quest Collections A Tribe Called Quest Love Movement A Tribe Called Quest Low End Theory A Tribe Called Quest Midnight Marauders A Tribe Called Quest People's Instinctive Trav Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothin' But a N Ab/Cd Cut the Crap! Ab/Cd Rock'n'roll Devil Abba Arrival + 2 Abba Classic:Masters.. Abba Icon Abba Name of the Game Abba Waterloo + 3 Abba.=Tribute= Greatest Hits Go Classic Abba-Esque Die Grosse Abba-Party Abc Classic:Masters.. Abc How To Be a Zillionaire+8 Abc Look of Love -Very Best Abyssinians Arise Accept Balls To the Wall + 2 Accept Eat the Heat =Remastered= Accept Metal Heart + 2 Accept Russian Roulette =Remaste Accept Staying a Life -19tr- Acda & De Munnik Acda & De Munnik Acda & De Munnik Adem-Het Beste Van Acda & De Munnik Live Met Het Metropole or Acda & De Munnik Naar Huis Acda & De Munnik Nachtmuziek Ace of Base Collection Ace of Base Singles of the 90's Adam & the Ants Dirk Wears White Sox =Rem Adam F Kaos -14tr- Adams, Johnny Great Johnny Adams Jazz.. Adams, Oleta Circle of One Adams, Ryan Cardinology Adams, Ryan Demolition -13tr- Adams, Ryan Easy Tiger Adams, Ryan Love is Hell Adams, Ryan Rock'n Roll Adderley & Jackson Things Are Getting Better Adderley, Cannonball Cannonball's Bossa Nova Adderley, Cannonball Inside Straight Adderley, Cannonball Know What I Mean Adderley, Cannonball Mercy -

Apuntes Sobre El Rock

Apuntes sobre el Rock Trabajo de investigación realizado por los alumnos de la materia Apreciación auditiva 1 dictada en Emu-Educación Dirección y Coordinación: Luis Aceto. Fuentes: http://es.wikipedia.org http://int.soyrock.com http://www.rock.com http://www.magicasruinas.com.ar/rock/revrock244.htm http://www.rincondelvago.com/ LA HISTORIA DEL ROCK ENCICLOPEDIA DIARIO LA NACION Publicada por el Diario La Nacion en 1993 Discografía existente de Las Bandas Definición: La Palabra rock se refiere a un lenguaje musical contemporáneo que engloba a diversos géneros musicales derivados del rock and roll, que a su vez proviene de una gran cantidad de fuentes, principalmente blues, rythm and blues y country, pero también del gospel y jazz INDICE Orígenes: 50´s pag.3 60´s, / 70´s pag.8 70´s / 80´s pag.10 80´s / 90´s pag.13 90´s pag.18 2000´s pag.19 géneros de música derivados del Rock & Roll pag.20 En la versión de Word presione Control + B para buscar el nombre de una banda Orígenes: Bluegrass Estractado De Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre El bluegrass (literalmente, "hierba azul") es un estilo musical incluido en el country que, en la primera mitad del siglo XX, se conoció como Hillbilly. Tiene sus raíces en la música tradicional de Inglaterra, Irlanda y Escocia, llevada por los inmigrantes de las Islas Británicas a la región de los Apalaches Denominación El nombre bluegrass procede del nombre del área en que se originó, llamada "región Bluegrass" (Bluegrass region), que incluye el norte del estado de Kentucky y una pequeña parte del sur del estado de Ohio. -

Issue 150.Pmd

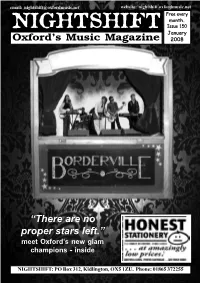

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 150 January Oxford’s Music Magazine 2008 “There are no proper stars left.” meet Oxford’s new glam champions - inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 TCT? NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] HELLO EVERYONE And a very Happy New Year to you all. January is, traditionally, a pretty quiet time for live music, but in the absence of many big-name touring bands, why not go out and catch a couple of new local acts instead. The rewards can be great and when the band you’ve just watched playing in your local pub venue are headlining the Academy in a year’s time, you can brag to your mates you were there at the beginning. We do it all the time and it really gets on people’s nerves. The New Year is a great time to think about new bands. As well as this month’s cover stars, we’d heartily recommend you checking out the likes of Hreda, 50ft Panda, Elapse-O, Traktors, International Jetsetters, Eduard Sounding Block and Raggasaurus, amongst the many great new bands in town. And of course, we just know that in the next few weeks we’ll discover a great new act who’ve barely played a handful of gigs yet. Last year we discovered Little Fish and by the end of the year they were supporting Supergrass at the Town Hall, a superb talent who look set to follow in the footsteps of Foals, and Young Knives in the coming months. -

The Prosthetic Novel and Posthuman Bodies

The Prosthetic Novel and Posthuman Bodies: Biotechnology and Literature in the 21st Century By Justin Omar Johnston A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2012 Date of final oral examination: April 19, 2012 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Anne McClintock, Professor, English Susan S. Friedman, Professor, English Robert Nixon, Professor, English Jon McKenzie, Associate Professor, English Tomislav Longinovic, Professor, Slavic Languages i TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOLWEDGMENTS………………………………………………………………………...ii ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………………...iii INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………………...1 The Biopolitical Context…………………………………………………………………..6 Prosthetic Humans and Posthuman Bodies………………………………………………14 A FEELING OF ATTACHMENT: THE POSTHUMAN POLITICS OF FENCES IN KAZUO ISHIGURO’S NEVER LET ME GO……………………………………………………………..21 Hailsham: The Disciplinary Fence………………………………………………………28 The Open Fence………………………………………………………………………….41 The Service-Station, Chemical-Substances and Subjectivity……………………………44 Wet Prosthetics and Vital Objects……………………………………………………….48 Affect, Agency, and “England, late-1990’s”…………………………………………….52 The Litterary Fence and Two Visions of Posthuman Politics…………………………...60 Counterpuntal Posthumanism…………………………………………………………....68 SPECIES TROUBLE IN MARGARET ATWOOD’S ORYX AND CRAKE……………………71 Corporate Domesticity…………………………………………………………………...82 Oryx and Difference……………………………………………………………………104 -

Donna Lewis Now in a Minute Free Download Donna Lewis – Now in a Minute (Expanded Edition) (2021) Tracklist: 01

donna lewis now in a minute free download Donna Lewis – Now In a Minute (Expanded Edition) (2021) Tracklist: 01. Without Love 02. Mother 03. I Love You Always Forever 04. Nothing Ever Changes 05. Simone 06. Love & Affection 07. Agenais 08. Fools Paradise 09. Lights of Life 10. Silent World 11. I Love You Always Forever (Philly Remix) 12. Don’t Ask 13. Pink Chairs 14. Have You Ever Loved 15. I Love You Always Forever (Sylk 130 Edit) [King Britt & John Wicks Remix] 16. Without Love (Radio Edit Long Version) 17. Simone (Lullaby Version) [Remix] 18. Beauty & Wonder 19. Mother (Remix) 20. Fool’s Paradise (Radio Edit) [Steven Fitzmaurice Remix] 21. Fool’s Paradise (Tevendale’s Tunnel Mix) 22. Fool’s Paradise (Donnapella) [Colin Tevendale Remix] 23. I Love You Always Forever (Sylk 130 Remix) 24. I Love You Always Forever (Sylk 130 Instrumental) [King Britt & John Wicks Remix] 25. I Love You Always Forever (Drumapella) [King Britt & John Wicks Remix] Release Name: Donna Lewis – Now In a Minute (Expanded Edition) (2021) Size: 247.07 MB Genre: Pop Quality: 320Kbps. Donna lewis now in a minute free download. Wykonawca | Artist: Donna Lewis Album: Now In a Minute (Expanded Edition) Gatunek | Genre: Pop Rok wydania | Year Of Release: 2021 Jakosc | Quality: 320 kbps Rozmiar | Size: 248 Mb. 01 – Without Love 02 – Mother 03 – I Love You Always Forever 04 – Nothing Ever Changes 05 – Simone 06 – Love & Affection 07 – Agenais 08 – Fools Paradise 09 – Lights of Life 10 – Silent World 11 – I Love You Always Forever (Philly Remix) 12 – Don’t Ask 13 – Pink Chairs -

Issue 160.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 160 November Oxford’s Music Magazine 2008 OnOn TargetTarget ForFor RockRock GloryGlory AA SILENTSILENT FILMFILM NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net NIGHTSHIFT’S WEBSITE has Tuesday 18th November. The undergone a major overhaul this event, organised by Generator month, making it easier to read the Project co-ordinator Paul Reed, magazine online and discuss local runs from 2-4pm and takes the music matters. Nightshift is form of an interactive discussion of available to read online in PDF topics such as getting established, format every month, plus there are costing and financial management, archive issues going back to 2005 promotion and marketing, venue available to browse. The management, licensing, dealing with ISIS will play a rare UK show at the Regal next month. The hugely th messageboard has been completely agents, artist liaison and influential Californian post-metal titans come to Oxford on Monday 8 revamped and visitors can now production. For full details of the December, one of only four UK shows, including an apperance at All easily join up to the forum and afternoon, visit Tomorrow’s Parties. Tickets for the show, are on sale now, priced post whatever pearls of wisdom www.generator.org.uk or phone £12.50, from wegottickets.com they want. Or just moan about Paul on 0191 245 0099. stuff. Go to at the Jericho Tavern next month. -

5204 Songs, 13.5 Days, 35.10 GB

Page 1 of 158 Music 5204 songs, 13.5 days, 35.10 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 I'm All the Way Up 3:12 I'm All the Way Up - Single Dj LaserJet 2 NozeBleedz (feat. Ripp Flamez) 2:39 NozeBleedz (feat. Ripp Flamez)… Ray Jr. 3 All of Me 3:04 The Piano Guys 2 The Piano Guys 4 All of Me 3:03 The Piano Guys 2 (Deluxe Edition) The Piano Guys 5 Three Times a Lady 3:41 Encore - Live at Wembley Arena Lionel Richie 6 The Way You Look Tonight 3:22 Nothing But the Best (Remaster… Frank Sinatra 7 Every Time I Close My Eyes 4:57 A Collection of His Greatest Hits Babyface, Mariah Carey, Kenny… 8 2U (feat. Justin Bieber) 3:15 2U (feat. Justin Bieber) - Single David Guetta 9 A Mother's Day 3:55 Simple Things Jim Brickman 10 Mean To Me 3:49 Bring You Back Brett Eldredge 11 Anywhere 4:04 Room 112 112 12 Don't Drop That Thun Thun 3:22 Don't Drop That Thun Thun - Sin… Finatticz 13 With You 4:12 Exclusive (The Forever Edition) Chris Brown 14 Like Jesus Does 3:19 Chief Eric Church 15 Nice & Slow 3:48 My Way Usher 16 Broccoli (feat. Lil Yachty) 3:45 Broccoli (feat. Lil Yachty) - Single DRAM 17 Grow Old With Me 3:09 Milk and Honey John Lennon 18 When I'm Holding You Tight (Re… 4:10 MSB (Remastered) Michael Stanley Band 19 Hot for Teacher 4:43 1984 Van Halen 20 Death of a Bachelor 3:24 Death Of A Bachelor Panic! At the Disco 21 Family Tradition 4:00 Hank Williams, Jr.'s Greatest Hit… Hank Williams, Jr. -

Stockport's Super Cinema and Variety Theatre

SUMMER AUTUMN 2016 Stockport’s Super Cinema and Variety Theatre MERSEY SQUARE BOX OFFICE: 0161 477 7779 STOCKPORT GROUP BOOKINGS: 0843 208 1495 CHESHIRE. SK1 1SP WWW.STOCKPORTPLAZA.CO.UK TED DOAN General Manager In October 1932 a vision was born for Stockport and the North West in the form of a Super Cinema and Variety Theatre with a sumptuous Café that would evoke the glorious glamour of the era in a building that was a palace for the giant silver screen, the greatest stage productions and delightful fine dining for the entire family to enjoy. Over 80 years later we are still providing you with this service in the finest Art Deco surroundings. This brochure that you are holding contains information about a host of sensational big screen and live stage events including this year’s blockbusting family pantomime ‘PETER PAN’ which stars the truly ‘nastiest’ Captain Hook imaginable played by the fabulous JOHN ALTMAN known to millions of TV fans as ‘Nasty’ Nick Cotton from Eastenders. 2016 has seen the launch of ‘The Green Room’ for superb cabaret style events and the success of this wonderful performance locale goes from strength to strength whilst our Silver Screen Film Concession which we also launched this year can be found on a number of the cinematic presentations detailed in this brochure. Finally, did you know that The Plaza has been the bespoke wedding venue of choice for many wonderful couples over the years and we continue to have the honour of being part of these life time celebrations to this very day.