Shakespeare, Nonconformity and Diversity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CIVIC GOSPELS: NETWORKS for SOCIAL CHANGE Civic Gospels: Networks for Social Change

CIVIC GOSPELS: NETWORKS FOR SOCIAL CHANGE Civic Gospels: Networks for Social Change Contents Civic Gospels: Networks for Social Change Religion and Reform Changing Political Landscapes Twentieth Century Civic Struggles People, Politics and Art Summary of Key Themes Sources from Birmingham Archives and Heritage Collections General Sources Written by Dr Andy Green, 2008. www.connectinghistories.org.uk/birminghamstories.asp Chamberlain Square. [Photo: A.Green] Joseph Chamberlain. [Highbury Collection] Joseph Chamberlain. Image from Banner Archive. [MS 1611/91/134] Image from Banner Archive. Louisa Ann Ryland. [Portaits Collection] [Portaits Ann Ryland. Louisa Civic Gospels: Networks for Social Change Understanding how social activity has created change Yet behind the famous figurehead of Chamberlain, in the past forms a basis for realising how change can many others became involved in trying to improve take place in the future. History books often focus Birmingham. Louisa Ann Ryland donated the grounds on the lives of ‘great men’, yet social transformations for Cannon Hill Park and funded hospitals; Quaker are also created by changing networks of activists industrialists like the Tangye brothers donated funds and workers. In the late 19th century, work began in for the Art Gallery. Soon, Birmingham was being Birmingham to dynamically alter the landscape and described as ‘the best governed city in the world’. provide better living conditions for inhabitants. The Yet behind this statement lay many struggles and term ‘civic gospel’ became used to express the idea of conflicts. In the 20th century, new social networks a new relationship between the town and its people. were needed to combat deeply rooted problems in This learning guide will explore the civic gospel and housing, education and everyday working life. -

Birmingham Exceptionalism, Joseph Chamberlain and the 1906 General Election

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository Birmingham Exceptionalism, Joseph Chamberlain and the 1906 General Election by Andrew Edward Reekes A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of Master of Research School of History and Cultures University of Birmingham March 2014 1 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The 1906 General Election marked the end of a prolonged period of Unionist government. The Liberal Party inflicted the heaviest defeat on its opponents in a century. Explanations for, and the implications of, these national results have been exhaustively debated. One area stood apart, Birmingham and its hinterland, for here the Unionists preserved their monopoly of power. This thesis seeks to explain that extraordinary immunity from a country-wide Unionist malaise. It assesses the elements which for long had set Birmingham apart, and goes on to examine the contribution of its most famous son, Joseph Chamberlain; it seeks to establish the nature of the symbiotic relationship between them, and to understand how a unique local electoral bastion came to be built in this part of the West Midlands, a fortress of a durability and impregnability without parallel in modern British political history. -

Beautiful Birmingham: Art and Welfare. By

BEAUTIFUL BIRMINGHAM: ART AND WELFARE Professor Ewan Fernie, ‘Everything to Everybody’ Project Director, introduces the fifth project theme ‘The time has come to give everything to everybody,’ said the founder of the world’s first great people’s Shakespeare Library, George Dawson. Dawson transfused the passion and mission of religion into contemporary civic life, providing a new model for municipal government, one which was ‘soon to be copied’, according to Tristram Hunt, ‘in London, Glasgow, and Manchester’. He always insisted that culture was key to welfare. ‘Not by bread alone’ was his scriptural rubric: ‘a city must have its parks as well as its prisons, its art gallery as well as its asylum, its books and its libraries as well as its baths and washhouses, its schools as well as its sewers,’ as a contemporary writer declared; ‘it must think of beauty and of dignity no less than of order and of health’. Dawson’s address at the opening of the opening of the Birmingham Reference Library in 1866 is the most famous statement of his ‘Civic Gospel’. Dawson insisted that Birmingham’s commitment to culture proved ‘that a great town is a solemn organism through which should flow, and in which should be shaped, all the highest, loftiest, and truest ends of man's intellectual and moral nature’. On the occasion of the opening of the new Children’s Hospital on Steelhouse Lane in 1862, Dawson said ‘he was delighted’ to applaud a building which bore witness to the fact ‘that a little beauty cost a little money, but gave great joy’. -

WILLIAM DYKE WILKINSON the Man Who Bought Moseley

WILLIAM DYKE WILKINSON The Man who bought Moseley William Dyke Wilkinson, always known as Dyke (his mother‘s maiden name), was born into a poor family in Lower Brearley Street, Summer Lane, Birmingham. His father was an educated man, but he made no attempt to get any schooling for his son. Dyke attended a dame-school, but claim he learnt nothing. He could go only when his mother could Afford the twopence a week. His date of birth was around 1835, and his earliest memories are of being taken to see the first train into Birmingham at Curzon Street in 1838, of Chartist Meetings in Snow Hill, and of celebrations for the wedding of Victoria and Albert. He claimed that he learnt to read by studying tradesmen's signs. Before the age of eight, Dyke was sent to work at a button-makers, Hammond Turner of Snow Hill, at ls/6d a week 7½ new pence), and a little later at Pemberton‘s brass- foundry at two shillings. His father at about this time came into a legacy of £200, and bought the Dog and Pheasant Public House, but the improvement in the family fortunes does not seem to have done Dyke any good from an educational point of view. At the age of 12½ years, he was apprenticed for 8½ years (until he was 21) to Routledge, rule-makers, of St Paul's Square. "I shiver now" Dyke writes "when I recall how I suffered during that damnable apprenticeship. There were twenty apprentices and very few men, no one to control us or show us a way to good of any sort.“ He and two other apprentices decided to run away to London and go to sea. -

Unitarian Hymn-Writers, to Meet the Require- Ments of the Student of Hymnody

BY H. W. STEPHENSON, M.A. PREFACE 1 HAVE not attempted, in these brief notices of Unitarian hymn-writers, to meet the require- ments of the student of Hymnody. My aim has been to interest the general reader in what has interested me. The text, therefore, is not bur- First +ublishbd, Dec. 1931 dened with footnotes and references. The chief sources of information, so far as they are known to me, are indicated in the Bibliography at the end of the book. In many cases, however, I have failed to find any memoir adequate to my purpose, and have had to make use of " appreciations " such as have appeared in this journal or that, scanty obituary notices, and scattered references in other biographies, memoirs, and reminiscences. Complete acknowledgment of sources is hardly possible, and may be regarded as unnecessary. Primarily, the Bibliography is given in order that any interested reader may not be entirely without guidance if there is the desire to know more than could be included in these pages. Though en- PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY RICHARD CLAY & SONS, LTD. tirely responsible for what is here presented, I Bungay, Suffolk gladly acknowledge my indebtedness to the Rev. v , PREFACE Valentine D. Davis for reading most of the copy in MS. and the whole of the proofs. For his long-continued and careful work on Unitarian Hymnody Mr. Davis has earned the gratitude of us all. CONTENTS PAGE I. JOHNJOHNS (1801-1847) . 9 11. SIR JOHNBOWRING (1792-1872) I 6 111. SARAHFLOWER ADAMS (1805-1848) . 25 IV. FREDERICHENRY HEDGE ( ~805-I890) . -

Birmingham's Shakespeare Memorial Library

EVERyTHInG TOEVEryBODy Birmingham’s Shakespeare Memorial Library Plan of the 1865 Library showing the location of the first Shakespeare Memorial Room which was destroyed in the 1879 fire Contents Foreword by Adrian Lester ............................... 5 After the Fire – The Shakespeare Memorial Room ....... 14-15 Introduction by Tom Epps ................................ 6 The 20th Century ..................................................................... 16 The ‘Our Shakespeare Club’ .............................. 8 The 21st Century ...................................................................... 17 Birmingham in the Early 19th Century .......... 9 The Shakespeare Memorial Library Collection ............. 18-29 George Dawson and the Civic Gospel ....... 10-11 Postscript by Professor Ewan Fernie ............................... 30-31 The Birmingham Free Library ........................ 12 Timeline .................................................................................... 33 The 1879 Fire .................................................... 13 Further Reading & Acknowledgements ............................... 34 EvERything tO EveryBODy Architectural woodwork in the Shakespeare Memorial Room 4 Birmingham’s Shakespeare Memorial Library Foreword Adrian Lester Patron of the Heritage Lottery-Funded ‘Everything to Everybody’ Project ‘The time has come to give everything to everybody’ George Dawson, founder of the Birmingham Shakespeare Memorial Library I was born and bred in so often underestimated as a Birmingham. I started -

Philanthropy in Birmingham and Sydney, 1860-1914: Class, Gender and Race

Philanthropy in Birmingham and Sydney, 1860-1914: Class, Gender and Race Elizabeth Abigail Harvey UCL This thesis is submitted for the degree of PhD I, Elizabeth Abigail Harvey, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 1 Abstract Philanthropy in Birmingham and Sydney, 1860-1914: Class, Gender and Race This thesis considers philanthropic activities directed towards new mothers and destitute children both “at home” and in a particular colonial context. Philanthropic encounters in Birmingham and Sydney are utilised as a lens through which to explore the intersections between discourses of race, gender and class in metropole and colony. Moreover, philanthropic and missionary efforts towards women and children facilitate a broader discussion of ideas of citizenship and nation. During the period 1860 to 1914 the Australian colonies federated to become the Australian nation and governments in both Britain and Australia had begun to assume some responsibility for the welfare of their citizens/subjects. However, subtle variations in philanthropic practices in both sites reveal interesting differences in the nature of government, the pace of transition towards collectivism, as well as forms of inclusion and exclusion from the nation. This project illuminates philanthropic and missionary men and women, as well as the women and children they attempted to assist. Moreover, the employment of “respectable” men and women within charities complicates the ways in which discourses of class operated within philanthropy. Interactions between philanthropic and missionary men and women reveal gendered divisions of labour within charities; the women and children they assisted were also taught to replicate normative (middle-class) gendered forms of behaviour. -

Dawson.Qxp Layout 1

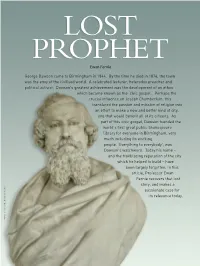

LOST PROPHET Ewan Fernie George Dawson came to Birmingham in 1844. By the time he died in 1876, the town was the envy of the civilised world. A celebrated lecturer, heterodox preacher and political activist, Dawson's greatest achievement was the development of an ethos which became known as the ‘civic gospel’. Perhaps the crucial influence on Joseph Chamberlain, this translated the passion and mission of religion into an effort to make a new and better kind of city, one that would benefit all of its citizens. As part of this civic gospel, Dawson founded the world's first great public Shakespeare library for everyone in Birmingham, very much including its working people. ‘Everything to everybody’, was Dawson's watchword. Today his name – and the trailblazing reputation of the city which he helped to build – have been largely forgotten. In this article, Professor Ewan Fernie recovers that lost story, and makes a passionate case for its relevance today. © Alex Parre/ Courtesy of Library of Birmingham of Library Courtesy Parre/ © Alex LOST PROPHET ‘Brummagem Dawson’ Edward Street, in the centre rummagem of town, on the Christian Dawson’ Carlyle gospel, but also on poetry, ‘ called him. ‘He Darwin and Mohammed; was a young he wanted a theology of man,’ we are told, ‘when he evolution, one that was came to Birmingham, and he continuously evolving. He came with the fire and was loved, by his friends, for freshness of youth.’ In a sense his honesty and energy, his Dawson WAS Birmingham. sparkle and commitment; In Emma, first published in but he was also, for a time, 1816, Jane Austen put the ‘the most hated man in following words in the mouth England’. -

Actes Des Congrès De La Société Française Shakespeare, 37 | 2019 Modernity Unbound: Birmingham, Shakespeare, and the French Revolutions 2

Actes des congrès de la Société française Shakespeare 37 | 2019 Shakespeare désenchaîné Modernity Unbound: Birmingham, Shakespeare, and the French Revolutions Ewan Fernie Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/shakespeare/4558 DOI: 10.4000/shakespeare.4558 ISSN: 2271-6424 Publisher Société Française Shakespeare Electronic reference Ewan Fernie, « Modernity Unbound: Birmingham, Shakespeare, and the French Revolutions », Actes des congrès de la Société française Shakespeare [Online], 37 | 2019, Online since 07 March 2019, connection on 30 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/shakespeare/4558 ; DOI : 10.4000/ shakespeare.4558 This text was automatically generated on 30 April 2019. © SFS Modernity Unbound: Birmingham, Shakespeare, and the French Revolutions 1 Modernity Unbound: Birmingham, Shakespeare, and the French Revolutions Ewan Fernie 1 He stood, on his plinth, in a relaxed attitude, as if ready to converse with anyone who happened to be passing through. His was a monument to an alternative Englishness; he was a prophet of a political modernity we frankly have yet to attain. His name was George Dawson (1821-1876), and his story represents a lost chapter of the history of English literature, and of Shakespeare criticism in particular—part of an unfortunate eclipse in British and even world history of Birmingham, Britain’s second city, now the youngest and one of the most diverse cities in Europe. During the 1870s and early 1880s, Birmingham acquired the reputation for being “the best-governed city in the world”;1 in 1887, the journalist and art critic, Alfred St Johnston, was able to write: “the Birmingham of today is perhaps the most artistic town in England.”2 Dawson’s most famous successor in Birmingham, Joseph Chamberlain, said Dawson’s name ran through the history of Birmingham institutions as through a stick of rock;3 Chamberlain also said if Birmingham had any special characteristics, they were George Dawson’s.4 When Dawson died, all Birmingham mourned. -

'Everything to Everybody' Project Team Ewan Fernie

‘Everything to Everybody’ Project Team Ewan Fernie (Project Director) Ewan is Chair, Professor and Fellow of Shakespeare Studies at the Shakespeare Institute, University of Birmingham, and Director of the 'Everything to Everybody' Project. Central to establishing the University's historic collaboration with the Royal Shakespeare Company and its pioneering MA in Shakespeare and Creativity (co-taught with the RSC), he has been a Visiting Professor at the University of Malmo and the University of Queensland (twice), and a Research Fellow of the Centre of Advanced Studies at the University of Munich. Ewan has nine books to his name, the latest of which is Shakespeare for Freedom: Why the Plays Matter. He is General Editor (with Simon Palfrey) of the influential Shakespeare Now! series. He has lectured across the world on Shakespeare, modernity and progressive culture. Ewan has always been committed to civic engagement and fomenting a more vital and creative relationship between 'high culture' and contemporary life. His 'Redcrosse' project invented a new civic liturgy for St George's Day, which premiered in Windsor Castle and Manchester Cathedral in 2012 and was adopted by the Royal Shakespeare Company for a high-profile event marking Coventry Cathedral's 50th anniversary. In conjunction with the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust and the Birmingham-based Ex Cathedra Choir, he commissioned a people's 'Shakespeare Masque' by the Poet Laureate, Carol Ann Duffy, and the major contemporary composer, Sally Beamish, for the big Shakespeare anniversary in 2016, when he was also Academic Advisor for the Library of Birmingham's 'Our Shakespeare' exhibition. Ewan was an ambassador for the British Council's Shakespeare Lives campaign (https://www.britishcouncil.org/voices-magazine/what-can-shakespeare-teach-us-about-freedom), and as part of that campaign he addressed large audiences in especially Eastern Europe. -

Pp16-17 Guy Sjogren HWM

BIRMINGHAM’S CIVIC GOSPEL Guy Sjögren Writing to his brother in the summer of 1824, the essayist Thomas Carlyle described Birmingham as a ‘pitiful’ town: ‘a mean congerie of bricks … streets ill-built and ill-paved … torrents of thick smoke issuing from a thousand funnels’. By the 1860s, little had been done to alleviate the squalor in which Carlyle’s ‘sooty artisans’ and their families lived and worked. The system of civic administration was largely ineffective in coping with a population of some 340,000 crammed into a warren of workshops and dwellings covering some five square miles. he town council Dawson asserted that a town was in the hands of council should be responsible for what has been the welfare of all within and called a subject to its authority just as ‘shopocracy’: men Parliament was for the well-being Tof an unprogressive tradesmen class of the nation as a whole. Dale who, whilst worthy in their way, endorsed this creed of practical lacked ideas and were filled with Christianity by saying that ‘the alarm at the prospect of large-scale eleventh commandment is that spending. Indeed, between 1853 thou shalt keep a balance sheet’. and 1858, council expenditure Whilst the three ministers might decreased by a third. However, have disagreed about elements of during this sterile period of local religious doctrine, they were administration, the seeds of a new united in the belief that the civic philosophy began to take municipal authority had a God- root. This was known as the ‘civic given responsibility to ‘prevent gospel’, and responsibility for the tens of thousands of children development and implementation from becoming orphans; to do of the civic gospel in Birmingham much to improve those miserable lay in the hands of a closely linked homes which are fatal not only triumvirate of non-conformist to health, but to decency and preachers, local politicians, and morality’; and to ‘give to the artists and architects. -

George Dawson's Civic Gospel and the Architecture Of

VIDES XV MATTHEW KEY ‘Through the Gains of Industry we promote Art’: George Dawson’s Civic Gospel and the architecture of the Improvement Scheme. This essay explores two artefacts from late Victorian Birmingham; a period in which the city went through remarkable transformation, culminating in one commentator describing it as ‘the best governed in the world’. The artefacts include George Dawson’s speech on the inauguration of Birmingham Reference Library (1866) and a drawing of Birmingham in 1886 by H.W. Brewer. These artefacts reveal how Unitarian preaching on civic morality was used to justify the hegemonic entrepreneurial politics of civic government during the period. However, what has been traditionally portrayed as a symbiosis of humanitarian progressivism, civic pride and business acumen, had less altruistic undertones. I hope that Corporations generally will become much more expensive than they have been – not expensive in the sense of wasting money, but that there will be such nobleness and liberality amongst the people of our towns and cities as will lead them to give their Corporations power to expend more money on those things which, as public opinion advances, are found to be essential to the health and comfort and improvement of our people. John Bright in a speech at Birmingham (January 1864) t is doubtful that even John Bright, the legendary radical and Liberal statesman, was aware of the magnitude of change that the Civic Gospel, whose tenets he Ihad alluded to in the above public address of the 26th January 1864, would