George Dawson's Civic Gospel and the Architecture Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birmingham Museums Supplement

BIRMINGHAM: ITS PEOPLE, ITS HISTORY Birmingham MUSEUMS Published by History West Midlands www.historywm.com fter six years of REVEALING BIRMINGHAM’S HIDDEN HERITAGE development and a total investment of BIRMINGHAM: ITS PEOPLE, ITS HISTORY A £8.9 million, The new ‘Birmingham: its people, its history’ galleries at Birmingham Museum & Art ‘Birmingham: its people, its Gallery, officially opened in October 2012 by the Birmingham poet Benjamin history’ is Birmingham Museum Zephaniah, are a fascinating destination for anyone interested in history. They offer an & Art Gallery’s biggest and most insight into the development of Birmingham from its origin as a medieval market town ambitious development project in through to its establishment as the workshop of the world. But the personal stories, recent decades. It has seen the development of industry and campaigns for human rights represented in the displays restoration of large parts of the have a significance and resonance far beyond the local; they highlight the pivotal role Museum’s Grade II* listed the city played in shaping our modern world. From medieval metalwork to parts for building, and the creation of a the Hadron Collider, these galleries provide access to hundreds of artefacts, many of major permanent exhibition which have never been on public display before. They are well worth a visit whether about the history of Birmingham from its origins to the present day. you are from Birmingham or not. ‘Birmingham: its people, its The permanent exhibition in the galleries contains five distinct display areas: history’ draws upon the city’s rich l ‘Origins’ (up to 1700) – see page 1 and nationally important l ‘A Stranger’s Guide’ (1700 to 1830) – see page 2 collections to bring Birmingham’s l ‘Forward’ (1830 to 1909) – see page 3 history to life. -

CIVIC GOSPELS: NETWORKS for SOCIAL CHANGE Civic Gospels: Networks for Social Change

CIVIC GOSPELS: NETWORKS FOR SOCIAL CHANGE Civic Gospels: Networks for Social Change Contents Civic Gospels: Networks for Social Change Religion and Reform Changing Political Landscapes Twentieth Century Civic Struggles People, Politics and Art Summary of Key Themes Sources from Birmingham Archives and Heritage Collections General Sources Written by Dr Andy Green, 2008. www.connectinghistories.org.uk/birminghamstories.asp Chamberlain Square. [Photo: A.Green] Joseph Chamberlain. [Highbury Collection] Joseph Chamberlain. Image from Banner Archive. [MS 1611/91/134] Image from Banner Archive. Louisa Ann Ryland. [Portaits Collection] [Portaits Ann Ryland. Louisa Civic Gospels: Networks for Social Change Understanding how social activity has created change Yet behind the famous figurehead of Chamberlain, in the past forms a basis for realising how change can many others became involved in trying to improve take place in the future. History books often focus Birmingham. Louisa Ann Ryland donated the grounds on the lives of ‘great men’, yet social transformations for Cannon Hill Park and funded hospitals; Quaker are also created by changing networks of activists industrialists like the Tangye brothers donated funds and workers. In the late 19th century, work began in for the Art Gallery. Soon, Birmingham was being Birmingham to dynamically alter the landscape and described as ‘the best governed city in the world’. provide better living conditions for inhabitants. The Yet behind this statement lay many struggles and term ‘civic gospel’ became used to express the idea of conflicts. In the 20th century, new social networks a new relationship between the town and its people. were needed to combat deeply rooted problems in This learning guide will explore the civic gospel and housing, education and everyday working life. -

Birmingham's Evangelical Free Churches and The

BIRMINGHAM’S EVANGELICAL FREE CHURCHES AND THE FIRST WORLD WAR by ANDY VAIL A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY School of History & Cultures College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham 2019 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis demonstrates that the First World War did not have a major long-term impact on the evangelical free churches of Birmingham. Whilst many members were killed in the conflict, and local church auxiliaries were disrupted, once the participants – civil and military – returned, the work and mission of the churches mostly continued as they had before the conflict, the exception being the Adult School movement, which had been in decline prior to the conflict. It reveals impacts on local church life, including new opportunities for women amongst the Baptist and Congregational churches where they began to serve as deacons. The advent of conscription forced church members to personally face the issue as to whether as Christians they could in conscience bear arms. The conflict also speeded ecumenical co-operation nationally, in areas such as recognition of chaplains, and locally, in organising local prayer meetings and commemorations. -

The Forge Brochure V7.Pdf

ABOVE AND BEYOND BJD ARE UNIQUE PROPERTY DEVELOPERS, WITH A PASSION FOR AUTHENTICITY. Over the past twelve years, we have specialised in unique renovation projects; extraordinary sites and developments which have allowed us to reinstate classic architecture back to its former glory. Due to our rich and experienced background in traditional craftsmanship, we understand the importance of detail and quality. With our diverse team, we successfully restore, revive and transform beautiful historic properties back to their origins. A number of our projects have been featured in magazines such as ‘Homes & Gardens’ and ‘Bedrooms, Bathrooms & Kitchens’. The Forge - Digbeth is our most recent development, which we have again partnered alongside Cedar Invest. With an extensive portfolio of commercial and residential ventures throughout the UK, Cedar offer over 60 years of combined experience and expertise which have helped turn The Forge from vision into reality. Together as custodians, we reinvent iconic properties preserving their history for generations to come. DELIVERING LUXURY LIFESTYLES THE FORGE IN DIGBETH PROVIDES Just moments away from Birmingham’s thriving PURCHASERS THE OPPORTUNITY TO City Centre and less than 5 Minutes away from Birmingham New Street and Grand Central it is easy ENJOY ALL THAT BIRMINGHAM HAS TO to forget you are so centrally located. The Forge is a OFFER ACROSS A WIDE VARIETY OF HOME stunning development that will deliver 140 luxury CHOICES FROM FIRST TIME BUYERS TO apartments in one and two bedroom residences. ESTABLISHED -

Jesse Collings, Agrarian Radical, 1880-1892

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1975 Jesse Collings, agrarian radical, 1880-1892. David Murray Aronson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Aronson, David Murray, "Jesse Collings, agrarian radical, 1880-1892." (1975). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 1343. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/1343 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JESSE COLLINGS, AGRARIAN RADICAL, 1880-1892 A Dissertation Presented By DAVID MURRAY ARONSON Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 1975 History DAVID MURRAY ARONSON 1975 JESSE COLLINGS, AGRARIAN RADICAL, 1880-1892 A Dissertation By DAVID MURRAY AFONSON -Approved ss to style and content by Michael Wolff, Professor of English Franklin B. Wickwire, Professor of History Joyce BerVraan, Professor of History Gerald McFarland, Ch<- History Department August 1975 Jesse Collings, Agrarian Radical, 1880-1892 David M. Aronson, B,A., University of Rochester M.A. , Syracuse University Directed by: Michael Wolff Jesse Collings, although -

Birmingham Exceptionalism, Joseph Chamberlain and the 1906 General Election

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository Birmingham Exceptionalism, Joseph Chamberlain and the 1906 General Election by Andrew Edward Reekes A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of Master of Research School of History and Cultures University of Birmingham March 2014 1 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The 1906 General Election marked the end of a prolonged period of Unionist government. The Liberal Party inflicted the heaviest defeat on its opponents in a century. Explanations for, and the implications of, these national results have been exhaustively debated. One area stood apart, Birmingham and its hinterland, for here the Unionists preserved their monopoly of power. This thesis seeks to explain that extraordinary immunity from a country-wide Unionist malaise. It assesses the elements which for long had set Birmingham apart, and goes on to examine the contribution of its most famous son, Joseph Chamberlain; it seeks to establish the nature of the symbiotic relationship between them, and to understand how a unique local electoral bastion came to be built in this part of the West Midlands, a fortress of a durability and impregnability without parallel in modern British political history. -

Beautiful Birmingham: Art and Welfare. By

BEAUTIFUL BIRMINGHAM: ART AND WELFARE Professor Ewan Fernie, ‘Everything to Everybody’ Project Director, introduces the fifth project theme ‘The time has come to give everything to everybody,’ said the founder of the world’s first great people’s Shakespeare Library, George Dawson. Dawson transfused the passion and mission of religion into contemporary civic life, providing a new model for municipal government, one which was ‘soon to be copied’, according to Tristram Hunt, ‘in London, Glasgow, and Manchester’. He always insisted that culture was key to welfare. ‘Not by bread alone’ was his scriptural rubric: ‘a city must have its parks as well as its prisons, its art gallery as well as its asylum, its books and its libraries as well as its baths and washhouses, its schools as well as its sewers,’ as a contemporary writer declared; ‘it must think of beauty and of dignity no less than of order and of health’. Dawson’s address at the opening of the opening of the Birmingham Reference Library in 1866 is the most famous statement of his ‘Civic Gospel’. Dawson insisted that Birmingham’s commitment to culture proved ‘that a great town is a solemn organism through which should flow, and in which should be shaped, all the highest, loftiest, and truest ends of man's intellectual and moral nature’. On the occasion of the opening of the new Children’s Hospital on Steelhouse Lane in 1862, Dawson said ‘he was delighted’ to applaud a building which bore witness to the fact ‘that a little beauty cost a little money, but gave great joy’. -

Traffic Movement Variation (TRO)

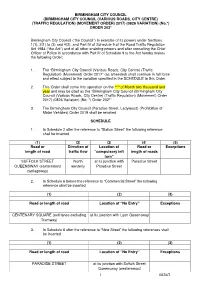

BIRMINGHAM CITY COUNCIL (BIRMINGHAM CITY COUNCIL (VARIOUS ROADS, CITY CENTRE) (TRAFFIC REGULATION) (MOVEMENT ORDER) 2017) (0826 VARIATION) (No.*) ORDER 202* Birmingham City Council (“the Council”) in exercise of its powers under Sections 1(1), 2(1) to (3) and 4(2), and Part IV of Schedule 9 of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 (“the Act”) and of all other enabling powers and after consulting the Chief Officer of Police in accordance with Part III of Schedule 9 to the Act hereby makes the following Order: 1. The “Birmingham City Council (Various Roads, City Centre) (Traffic Regulation) (Movement) Order 2017” (as amended) shall continue in full force and effect subject to the variation specified in the SCHEDULE to this Order. 2. This Order shall come into operation on the ** th of Month two thousand and year and may be cited as the “Birmingham City Council (Birmingham City Council (Various Roads, City Centre) (Traffic Regulation) (Movement) Order 2017) (0826 Variation) (No. *) Order 202*”. 3. The Birmingham City Council (Paradise Street, Ladywood) (Prohibition of Motor Vehicles) Order 2019 shall be revoked SCHEDULE 1. In Schedule 2 after the reference to “Station Street” the following reference shall be inserted (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) Road or Direction of Location of Road or Exceptions length of road traffic flow “compulsory left length of roads turn” SUFFOLK STREET North at its junction with Paradise Street QUEENSWAY (easternmost westerly Paradise Street carriageway) 2. In Schedule 6 before the reference to “Commercial Street” the following reference shall be inserted (1) (2) (3) Road or length of road Location of “No Entry” Exceptions CENTENARY SQUARE (exit lanes excluding at its junction with Lyon Queensway Tramway) 3. -

The Sermon in Nineteenth-Century British Literature and Society

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Victorian Sermonic Discourse: The Sermon in Nineteenth-Century British Literature and Society A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Jeremy Michael Sell June 2016 Dissertation Committee: Dr. John Ganim, Chairperson Dr. Susan Zieger Dr. John Briggs Copyright by Jeremy Michael Sell 2016 The Dissertation of Jeremy Michael Sell is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements Anyone who has been through the trials and tribulations of graduate school and writing a dissertation knows that as solitary as it may at times seem, it is not a journey taken alone. I have many people to thank for helping bring this nearly-decade long sojourn to a successful conclusion. To begin, I want to remember Dr. Emory Elliott. His first book, Power and the Pulpit in Puritan New England, was one I discovered when I was first applying to PhD programs, and it gave me hope that there would be a professor at UCR who could relate to my interest in studying the sermon. After taking a course from him, I approached Dr. Elliott about chairing my committee; a journal entry I wrote the following day reads, “Dr. Elliott on board and enthusiastic.” But, not long afterwards, I received word that he unexpectedly and suddenly passed away. I trust that this work would have met with the same degree of enthusiasm he displayed when I first proposed it to him. With Dr. Elliott’s passing, I had to find someone else who could guide me through the final stages of my doctorate, and Dr. -

Birmingham the Heart and Soul of the West Midlands Birmingham 2–3 the Heart and Soul of the West Midlands

Birmingham The heart and soul of the West Midlands Birmingham 2–3 The Heart and Soul of the West Midlands Brilliant Birmingham Birmingham Facts and Stats Welcome to Birmingham, the The second largest city in the UK, rich in Birmingham Town Hall and the Argent history and scattered with hidden gems, Centre. Birmingham’s innovation continues UK’s largest regional city: Birmingham is a hub of culture and today, being home to one of the UK’s a multicultural and innovation. With influences from across the premier research universities, as well as world, you can encounter anything from a Britain’s leading digital hub. innovative heartland at the English folk festival to Brazillian street art centre of Britain’s new with a world of experiences in between. However, Birmingham’s history lays far Divided into distinct quarters, the city centre beyond the borders of the West Midlands. Total population: Population growth to 2035: Percentage of people aged under 25: railway revolution. offers a unique mix of cultural attractions, as Birmingham is a multicultural city, which well as a range of restaurants, including celebrates its links to numerous countries several Michelin starred and countless bars and cultures. The city hosts over 50 festivals and clubs. Birmingham has something to throughout the year to celebrate diversity in m % % offer each of the 34 million visitors who are it’s own spectacular fashion. Welcoming the 1.1 16 37 drawn to the city every year. Chinese New Year in style, Birmingham’s free annual street festival attracts up to 30,000 Birmingham has a history of innovation and people. -

WILLIAM DYKE WILKINSON the Man Who Bought Moseley

WILLIAM DYKE WILKINSON The Man who bought Moseley William Dyke Wilkinson, always known as Dyke (his mother‘s maiden name), was born into a poor family in Lower Brearley Street, Summer Lane, Birmingham. His father was an educated man, but he made no attempt to get any schooling for his son. Dyke attended a dame-school, but claim he learnt nothing. He could go only when his mother could Afford the twopence a week. His date of birth was around 1835, and his earliest memories are of being taken to see the first train into Birmingham at Curzon Street in 1838, of Chartist Meetings in Snow Hill, and of celebrations for the wedding of Victoria and Albert. He claimed that he learnt to read by studying tradesmen's signs. Before the age of eight, Dyke was sent to work at a button-makers, Hammond Turner of Snow Hill, at ls/6d a week 7½ new pence), and a little later at Pemberton‘s brass- foundry at two shillings. His father at about this time came into a legacy of £200, and bought the Dog and Pheasant Public House, but the improvement in the family fortunes does not seem to have done Dyke any good from an educational point of view. At the age of 12½ years, he was apprenticed for 8½ years (until he was 21) to Routledge, rule-makers, of St Paul's Square. "I shiver now" Dyke writes "when I recall how I suffered during that damnable apprenticeship. There were twenty apprentices and very few men, no one to control us or show us a way to good of any sort.“ He and two other apprentices decided to run away to London and go to sea. -

City of Birmingham Choir Concerts from 1964

City of Birmingham Choir concerts from 1964. Concerts were conducted by Christopher Robinson and took place in Birmingham Town Hall with the CBSO unless otherwise stated. Messiah concerts and Carols for All concerts are listed separately. 1964 Mar 17 Vaughan Williams: Overture ‘The Wasps’ Finzi: Intimations of Immortality Vaughan Williams: Dona Nobis Pacem Elizabeth Simon John Dobson Peter Glossop Christopher Robinson conducts the Choir for the first time Jun 6 Britten: War Requiem Heather Harper Wilfred Brown Thomas Hemsley Performed in St Alban’s Abbey Meredith Davies’ final concert as conductor of the Choir Nov 11 & 12 Britten: War Requiem (Nov 11 in Wolverhampton Civic Hall Nov 12 in Birmingham Town Hall) Jacqueline Delman Kenneth Bowen John Shirley-Quirk Boy Choristers of Worcester Cathedral CBSO concert conducted by Hugo Rignold 1965 Feb 27 Rossini: Petite Messe Solennelle Barbara Elsy Janet Edmunds Gerald English Neil Howlett Colin Sherratt (Piano) Harry Jones (Piano) David Pettit (Organ) Performed in the Priory Church of Leominster Mar 11 Holst: The Planets CBSO concert conducted by Hugo Rignold Mar 18 Beethoven: Choral Symphony Jennifer Vyvyan Norma Proctor William McAlpine Owen Brannigan CBSO concert conducted by Hugo Rignold Mar 30 Elgar: The Dream of Gerontius Marjorie Thomas Alexander Young Roger Stalman May 18 Duruflé: Requiem Poulenc: Organ Concerto Poulenc: Gloria Elizabeth Harwood Sybil Michelow Hervey Alan Roy Massey (Organ) 34 Jun 2 Rossini: Petite Messe Solennelle Elizabeth Newman Miriam Horne Philip Russell Derek