Reflections on the History of Computer Education in Schools in Victoria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monash University's Campus LAN in the 1980S

MONET – Monash University’s Campus LAN in the 1980s – A Bridge to Better Networking Barbara Ainsworth, Neil Clarke, Chris Avram, Judy Sheard To cite this version: Barbara Ainsworth, Neil Clarke, Chris Avram, Judy Sheard. MONET – Monash University’s Campus LAN in the 1980s – A Bridge to Better Networking. IFIP International Conference on the History of Computing (HC), May 2016, Brooklyn, NY, United States. pp.23-48, 10.1007/978-3-319-49463-0_2. hal-01620140 HAL Id: hal-01620140 https://hal.inria.fr/hal-01620140 Submitted on 20 Oct 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License MONET – Monash University’s Campus LAN in the 1980s – a Bridge to Better Networking Barbara Ainsworth1, Neil Clarke2, Chris Avram1, Judy Sheard1 1 Monash University, Monash Museum of Computing History, Melbourne, Australia {Barbara.Ainsworth,Chris.Avram,Judy.Sheard}@monash.edu 2 Deakin University, Audiovisual and Networks Unit, Melbourne, Australia [email protected] Abstract. Monash University, Australia developed an in-house local area network called MONET during the 1980s to meet the needs of the university’s computer users. -

DLTV Journal 5 1.Cdr

DLTV 5.1 JOURNAL The Journal of Digital Learning and Teaching Victoria V o l u m e 5 | N u m b e r 1 | 2 0 1 8 | I S S N 2 2 0 5 - 3 6 1 1 ( O n l i n e ) Contents EDITORIAL 2 DLTV Journal Pennie White and Roland Gesthuizen The Journal of Digital Learning and Teaching Victoria FROM THE PRESIDENT 3 Editors Ben Gallagher Pennie White Roland Gesthuizen VALE MARK RICHARDSON 5 Melinda Cashen Associate Editors Narissa Leung DIGICON18 AND THE DLTV AWARDS 6 Clark Burt Ben Gallagher Catherine Newington Irene Anderson BITS AND BYTES 8 Cameron Hocking VCE Programming Language Options to Consider Maria-Ana Sanchez Publisher Mind Mapping with VCE Software Development Digital Learning and Teaching Victoria Chris Paragreen Starting a STEM Space The DLTV Committee Celeste Pettinella of Management 2018-2019 Ben Gallagher- President TIME CAPSULE 11 Andrew Williamson - Vice President From CEGV 1979 to ACEC 2000: Australian computers in education Mel Cashen - Treasurer conferences come of age Narissa Leung - Secretary Anne McDougall & Barry McCrae Irene Anderson (co-opted) Clark Burt HOW DOES THE USE OF GAMEMAKER SOFTWARE FOSTER THE 16 Ian Fernee DEVELOPMENT OF CREATIVE PROBLEM– SOLVING SKILLS IN BOYS? Roland Gesthuizen Matthew Harrison Ben Marr Robert Maalouf Catherine Newington BUILDING A PLATFORM FOR CHANGE AND REDESIGNING 26 Fiona Turner (co-opted) THE ROLE OF A RESELLER Greg Bowen 61 Blyth Street Brunswick VIC 3056 Australia USING ROBOTS AND DIGITECH FOR STUDENTS WITH DISABILITIES 27 Phone: +61 3 9349 3733 K. Clark Burt Web: www.dltv.vic.edu.au Email: [email protected] Twitter: @DLTVictoria DITCHING THE DESKS 31 Flexible learning spaces focus on helping students be productive, comfortable Invitation to send contributions to Tim Douglas [email protected] ABN 20 211 799 378 3 POWERFUL WORDS CAN UNLOCK COMPUTER SCIENCE SUCCESS 35 Registration Number A0060428T The Digital Learning and Teaching Journal is Janice Mak published as a resource for all educators engaged in the effective use of information and communication technologies for teaching and learning. -

The Codeeazee Tool Support for Computational Thinking in Python

EJERS, European Journal of Engineering Research and Science Vol. 3, No. 3, March 2018 The CodeEazee Tool Support for Computational Thinking in Python Francisca O. Oladipo, and Memunat A. Ibrahim the non-linear and dynamic programming processes as static Abstract—This paper describes the development of and linear, making them assume that the link between every CodeEazee, a problem solving, self- teaching tool for python problem and solution is simple and direct [10]. programming which deploys templates and games. In this Basically, two factors are fundamental to teaching work, the authors conducted a survey to determine the factors programming, which are: choosing a programming language responsible for the reduced interests of learners in programming, reviewed the various approaches used in and choosing an effective approach for teaching [11]. These teaching programming, and developed a python-for-python choices are essential to the students understanding teaching system to teach programming skills, computational programming and acquiring the necessary programming thinking, algorithms’ design, programming in general and skills, and also to prepare them for other higher Python programming specifically. The work would show how programming course [12]; and a wrong choice of the third party environment had enabled users with limited or programming language [9] or teaching approach can make no programming experiences to design applications through peer supports, templates and gamification, embedded in a learning programming difficult [13]. Similarly, knowing the programming tool. students’ learning styles will help in determining the best teaching approach to be used [14], leading to the conclusion Index Terms—Algorithms; Computation; Problem-Solving that finding and employing an appropriate teaching Skills; Programming; Python. -

Education in Australia Streams in the History Of

STREAMS IN THE HISTORY OF COMPUTER EDUCATION IN AUSTRALIA An Overview of School and University Computer Education Arthur Tatnall and Bill Davey Victoria University and RMIT University Australia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: In world terms, Australia moved into the educational computing, both at the Higher Education and School levels, very early. This paper looks at how university subjects, and later how whole courses in computing evolved in Australia and how these had very little effect on the later use of computers in schools. We briefly examine how computers were first used in schools, and the influences that put them there and decided how they could be used. We relate an established a model of the growth of academic subjects to the emergence of the discipline area of computing, and in particular, to the Victorian Year 12 Computer Science subject. Key words: Computer science; Information systems; Computer education; Computers across the curriculum; School computing; University computing. 1. INTRODUCTION The Commonwealth of Australia is a federation of six states and two territories each having a considerable degree of independence. Constitutionally, education is the role of the individual State; the Commonwealth Government being limited to co-ordination, leadership and the funding of specific projects. While also considering Australia-wide issues, this paper will concentrate its perspective on the state of Victoria. In this paper we will provide an overview of the evolution and history of the various streams of educational computing in Australia: University-level Computer Science and Information Systems courses, Primary and Secondary School courses teaching about computing, and the use of computers in other 84 Arthur Tatnall and Bill Davey school subjects. -

Handbook 1981

THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE FACULTY 0F SCIENCE HANDBOOK 1981 PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY THIS HANDBOOK CONTAINS: 1. The courses offered by the faculty of Science. 2. The relevant University regulations. 3. Other information of importance to students. This handbook is your book of rules for work towards a Science degree. Read it carefully and use it to select combinations of subjects which will allow you to take the subjects you wish in subse- quent years. Consult faculty or departmental advisers before making your final enrolment. The complete Statutes and Regulations of the University may be found in the University Calendar which may be seen in the Baillieu Library or bought at the University Bookroom. Prospective students are referred to another booklet Guide to Science Courses. It Is distributed to most Victorian secondary schools and is available from the University Bookroom or the faculty office. The Science Faculty Handbook should be read in conjunction with the Student Diary issued free to all enrolling or re-enroll- ing students. A map of the University will be found in the Students' Infor- mation Booklet. In exceptional circumstances the Council is empowered to suspend subjects and to vary the syllabus of a subject. Details of any such altera- tion will be available from the faculty office and will be announced on departmental noticeboards. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Important Dates for Students Front cover This Handbook Contains 2 Preface 5 CHAPTER 1 General Information for AR Students 6 Continuing Education Student Diary CHAPTER 2 -

2015 Queensland Pearcey Entrepreneur Award

2018 Pearcey Day at DIF Tuesday, 28 August 2018 Pearcey Foundation Inc. Twitter: @pearcey_org #DIFVIC #DIFVicFeatureEvent https://pearcey.org.au Welcome Celebrating the Past; Informing the Present; Inspiring the Future Dr Peter Thorne Chairman, National Committee Twitter: @pearcey_org https://pearcey.org.au #DIFVIC #DIFVicFeatureEvent 2 Panel Speakers Dr Matthew Connell Powerhouse Museum Twitter: @pearcey_org https://pearcey.org.au #DIFVIC #DIFVicFeatureEvent 3 Panel Speakers David Piltz Telstra/Heritage Communication Ltd Twitter: @pearcey_org https://pearcey.org.au #DIFVIC #DIFVicFeatureEvent 4 TELECOMMUNICATIONS HERITAGE David Piltz Telstra Corp Ltd TELSTRA TELSTRA TELSTRA TEMPLATE TEMPLATE BLUE BLUE 4X3BETA4X3BETA| | TELPPTV4 TELPPTV4 COMMUNICATIONS HISTORY • Communication dates back Millennia ➢ Indigenous message sticks ➢ Smoke Signals ➢ Optical Telegraph by Semaphore Flags • Wired Communication ➢ Telegraph ➢ Telephone ➢ Switchboards ➢ Electromechanical exchanges ➢ Optical fibre • Wireless Communication ➢ Radio Telegraphy ➢ Radio Broadcasting ➢ Radio Duplex Voice • Advancements ➢ Semiconductors ➢ Computers ➢ Miniaturisation and Handheld devices HERITAGE ASSETS IN PMG / TELECOM / TELSTRA • Passionate individuals within Telstra and its predecessor entities have been working to protect the company’s historical legacy for many years. • The Collection has gone through various phases of organisational sponsorship and management over many years – this has included paid historical officers and individual state based approaches. • A ‘Telstra -

Handbook, 1978

THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE FACULTY 0F ARTS HANDBOOK, 1978 PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY ADDENDUM (This paragraph to be read together with page 71.) STUDENT WORK LOAD Students will note that the Handbook specifies hours for prescribed lectures and classes. In all departments, essays and reading guides impose extra load on student time. Supervision and correction of essays and guidance in reading are the responsibility of staff and occasion many hours of individual consultation between students and staff. Students should be aware that a minimum of 8 hours per week per subject will need to be spent in these required activities, in addition to the formal contact hours specified in the details for each subject. In exceptional circumstances the Council is empowered to suspend subjects and to vary the syllabus of a subject. Details of any such alteration will be available from the appropriate Faculty or Board of Studies and will be announced on departmental notice-boards. SCIENCE SUBJECTS — ENROLMENT PROCEDURE Students enrolling for any subjects in Computer Science, Mathematics, Statistics or any other subject listed under the heading 'Science Subjects' In section 'Details of Subjects' should consult the Faculty of Science Handbook for correct subject and unit numbers; and should also consult the Assistant to the Dean of Science. TABLE OF CONTENTS Officers of the Faculty of Arts 6 Directory 7 Senior Teaching Staff 9 General Information 15 Student Information Booklet 1978 15 Dates in 1978 15 Enrolment 15 Location of Lectures and Tutorials 16 Part-time Students 16 Evening Lectures 16 Leave of Absence 16 University General Principles of Selection for First-Year Courses 17 Selection Into Arts 19 Application Procedures for New Students (including Graduates) 19 Transfers from other faculties 19 Students wishing to resume an Arts Course 19 Special Principles of Selection in Faculty of Arts 19 Undergraduate Quota 19 Sub-quotas 20 Subject Quotas 21 Reservations of Places in B.A. -

Faculty of Engineering Handbo

FACULTY OF ENGINEERING HANDBOOK 1978 THE UNIVERSITY OF NEWCASTLE NEW SOUTH WALES 2308 ISSN 031 3 - 0002 Telephone - Newcastle 68 0401 One dollar fifty Recommended price AN INTRODUCrrON TO THE FACULTY AND ITS DEPARTMENTS A Message from the Dean On behalf of the staff of the Faculty of Engineering, I wish to extend a very warm welcome to all students - those who are entering the University and the Faculty for the first time and those who are returning to commence another year of studies. To new and prospective students may I begin by briefly 'acquainting you of the structure of the Faculty of Engineering. The Faculty comprises five Departments: Chemical, Civil, Electrical and Mech anical Engineering and Metallurgy. In addition to the Bachelors degree programmes offered in these five major areas, the Department of Electrical Engineering offers the B.E. in Computer Engineering, the Department of Mechanical Engineering the B.E. in Industrial Engineering, while the Deparment of Civil Engineering now offers a complete four year Bachelor of Surveying course. Courses are available on a full-time or part-time basis, or a combination of these, and, in 1978 Sandwich Patterns will be available in the Electrical and Mechanical degree courses. In each degree programme the opportunity for some specialization exists in the later course years through a wide selection of technical electives. The Faculty is also active at the post graduate level, offering formal courses leading to the Diploma in Industrial Engineering and Master of Engineering Science, as well as providing opportunities for postgraduate research at Masters and Doctorate levels. -

CODING and COMPUTATIONAL THINKING What Is the Evidence?

CODING AND COMPUTATIONAL THINKING What is the Evidence? education.nsw.gov.au About the research team About the Australian Computing Academy James Curran is an Associate Professor in the School The University of Sydney leads the Australian of Information Technologies, University of Sydney. Computing Academy to provide the intellectual, He is Director of the National Computer Science technical, and practical leadership needed to fulfil School (NCSS), the largest computer science school the ambitious goals of the Australian Curriculum: outreach program in Australia. Last year, over 10,000 Digital Technologies. This includes working directly students and teachers participated in the 5-week with jurisdictions and systems as they implement the NCSS Challenge. James is a co-founder of Grok Digital Technologies curriculum. For more information Learning, an Edtech startup that aims to teach about the Academy please visit aca.edu.au. children everywhere how to code. He was a writer on the Australian Curriculum: Digital Technologies, the new national computing curriculum. In 2014, Australian Computing Academy James was named ICT Leader of the Year by the ICT A/Prof James R. Curran Educators of NSW and the Australian Council for A/Prof Karsten A. Schulz Computers in Education. Amanda Hogan Karsten Schulz is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Engineering and Information Technologies School of Information Technologies, University of The University of Sydney, NSW 2006 Sydney. Karsten has a PhD in Computer Science and A/Prof James R. Curran a Bachelor in Electrical Engineering with a focus Phone: (02) 9036 6037 / 0431 013 320 on Software Engineering. For 10 years, Karsten led [email protected] aca.edu.au the research division of a large multi-national ICT company in Australia and the Asia-Pacific Region and between 2013 and 2016 he led the national Digital Careers Program. -

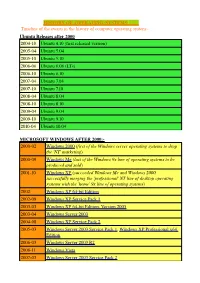

HISTORY of OPERATING SYSTEMS Timeline of The

HISTORY OF OPERATING SYSTEMS Timeline of the events in the history of computer operating system:- Ubuntu Releases after 2000 2004-10 Ubuntu 4.10 (first released version) 2005-04 Ubuntu 5.04 2005-10 Ubuntu 5.10 2006-06 Ubuntu 6.06 (LTs) 2006-10 Ubuntu 6.10 2007-04 Ubuntu 7.04 2007-10 Ubuntu 7.10 2008-04 Ubuntu 8.04 2008-10 Ubuntu 8.10 2009-04 Ubuntu 9.04 2009-10 Ubuntu 9.10 2010-04 Ubuntu 10.04 MICROSOFT WINDOWS AFTER 2000:- 2000-02 Windows 2000 (first of the Windows server operating systems to drop the ©NT© marketing) 2000-09 Windows Me (last of the Windows 9x line of operating systems to be produced and sold) 2001-10 Windows XP (succeeded Windows Me and Windows 2000, successfully merging the ©professional© NT line of desktop operating systems with the ©home© 9x line of operating systems) 2002 Windows XP 64-bit Edition 2002-09 Windows XP Service Pack 1 2003-03 Windows XP 64-bit Edition, Version 2003 2003-04 Windows Server 2003 2004-08 Windows XP Service Pack 2 2005-03 Windows Server 2003 Service Pack 1, Windows XP Professional x64 Edition 2006-03 Windows Server 2003 R2 2006-11 Windows Vista 2007-03 Windows Server 2003 Service Pack 2 2007-11 Windows Home Server 2008-02 Windows Vista Service Pack 1, Windows Server 2008 2008-04 Windows XP Service Pack 3 2009-05 Windows Vista Service Pack 2 2009-10 Windows 7(22 occtober 2009), Windows Server 2008 R2 EVENT IN HISTORY OF OS SINCE 1954:- 1950s 1954 MIT©s operating system made for UNIVAC 1103 1955 General Motors Operating System made for IBM 701 1956 GM-NAA I/O for IBM 704, based on General Motors -

50 Years of IFIP - Developments and Visions IFIP – the International Federation for Information Processing

50 Years of IFIP - Developments and Visions IFIP – The International Federation for Information Processing IFIP was founded in 1960 under the auspices of UNESCO, following the First World Computer Congress held in Paris the previous year. An umbrella organi- zation for societies working in information processing, IFIP’s aim is two-fold: to support information processing within its member countries and to encourage technology transfer to developing nations. As its mission statement clearly states, IFIP’s mission is to be the leading, truly international, apolitical organization which encourages and assists in the development, ex- ploitation and application of information technology for the benefit of all people. IFIP is a non-profitmaking organization, run almost solely by 2500 volunteers. It operates through a number of technical committees, which organize events and publications. IFIP’s events range from an international congress to local seminars, but the most important are: • The IFIP World Computer Congress, held every second year; • Open conferences; • Working conferences. The flagship event is the IFIP World Computer Congress, at which both invited and contributed papers are presented. Contributed papers are rigorously refereed and the rejection rate is high. As with the Congress, participation in the open conferences is open to all and papers may be invited or submitted. Again, submitted papers are stringently ref- ereed. The working conferences are structured differently. They are usually run by a working group and attendance is small and by invitation only. Their purpose is to create an atmosphere conducive to innovation and development. Refereeing is less rigorous and papers are subjected to extensive group discussion. -

Turning Points in Computer Education

Turning Points in Computer Education Bill Davey1 and Kevin R. Parker2 1 RMIT University, Melbourne Australia [email protected] 2 College of Business, Idaho State University, Pocatello USA [email protected] Abstract. This history of computers in education covers two continents. By analysing the experiences of two people a set of turning points in history is identified. These turning points are in the experienced history and so indicate the impact of changes on the citizens of two countries. Keywords: Computers, education, history. 1 Introduction One view of the history of computers and education starts with the use of computers like CSIRAC, used some educational purposes starting in November 1949 [1]. We can be certain that large scale roll outs of educational programs had been established by 1968 as, in that year, reports were being published regarding the success of the use of PLATO terminals [2-4]. Despite the certainty of facts supporting this view of his- tory, questions remain: “How widespread were computers in education?” and “what were the real impacts on people’s lives from the computer and when did they become real for the ordinary person?” Trends in history can be seen by following the careers of giants and pioneers. An- other view can be obtained by following the paths of those who are swept along by history. This paper examines the career of two information systems academics from either side of the Pacific, one Australian and one American. These two societies, which were responsible for producing the first computers and using them as educa- tional aids, are considered to be at the forefront of computers in education.