Harvard Extension School – Capstone Project Journalism Graduate Program Advisor: Angelia Herrin May 15, 2015 Missing in Mammot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inyo National Forest Visitor Guide

>>> >>> Inyo National Forest >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> Visitor Guide >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> $1.00 Suggested Donation FRED RICHTER Inspiring Destinations © Inyo National Forest Facts “Inyo” is a Paiute xtending 165 miles Bound ary Peak, South Si er ra, lakes and 1,100 miles of streams Indian word meaning along the California/ White Mountain, and Owens River that provide habitat for golden, ENevada border between Headwaters wildernesses. Devils brook, brown and rainbow trout. “Dwelling Place of Los Angeles and Reno, the Inyo Postpile Nation al Mon ument, Mam moth Mountain Ski Area National Forest, established May ad min is tered by the National Park becomes a sum mer destination for the Great Spirit.” 25, 1907, in cludes over two million Ser vice, is also located within the mountain bike en thu si asts as they acres of pris tine lakes, fragile Inyo Na tion al For est in the Reds ride the chal leng ing Ka mi ka ze Contents Trail from the top of the 11,053-foot mead ows, wind ing streams, rugged Mead ow area west of Mam moth Wildlife 2 Sierra Ne va da peaks and arid Great Lakes. In addition, the Inyo is home high Mam moth Moun tain or one of Basin moun tains. El e va tions range to the tallest peak in the low er 48 the many other trails that transect Wildflowers 3 from 3,900 to 14,494 feet, pro vid states, Mt. Whitney (14,494 feet) the front coun try of the forest. Wilderness 4-5 ing diverse habitats that sup port and is adjacent to the lowest point Sixty-five trailheads provide Regional Map - North 6 vegetation patterns ranging from in North America at Badwater in ac cess to over 1,200 miles of trail Mono Lake 7 semiarid deserts to high al pine Death Val ley Nation al Park (282 in the 1.2 million acres of wil der- meadows. -

Mount Whitney Via the East Face Trip Notes

Mount Whitney via The East Face Trip Notes 2.18 Mount Whitney via the East Face This is the classic route up the highest peak in the lower forty eight states. The 2000 foot-high face was first as- cended by the powerful team of Robert Underhill, Norman Clyde, Jules Eichorn and Glen Dawson on August 16, 1931. These were the finest climbers of the time; their ascent time of three and a quarter hours is rarely equalled by modern climbers with their tight rock shoes and the latest in climbing hardware. Dawson returned to make the sec- ond ascent of the route and in 1934 Eichorn pioneered the airy Tower Traverse that all current day climbers utilize. Clyde became legendary in the Sierra for both his unequaled number of Sierra first ascents and the size of the packs he carried. Underhill later remarked that on the approach to the East Face Clyde’s pack was “an especially pictur- esque enormity of skyscraper architecture.” Times have changed but the East Face remains a great climb. While only rated 5.6 do not underestimate it! You will be at over 14,000 feet carrying a small pack with the essentials for the day, and ascending about 12 pitches of continuous climbing. Itinerary Day One: The Approach. Starting at the 8,640 foot Whitney Portal we hike Whitney Trail for less than a mile before heading up the steep North Fork of Lone Pine Creek. The trail here is non-maintained and rough with creek crossings and rocks to scramble up and over. -

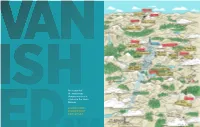

Matthew Greene Were Starting to Understand the Grave the Following Day

VANISHED An account of the mysterious disappearance of a climber in the Sierra Nevada BY MONICA PRELLE ILLUSTRATIONS BY BRETT AFFRUNTI CLIMBING.COM — 61 VANISHED Three months earlier in July, the 39-year-old high school feasted on their arms. They went hiking together often, N THE SMALL SKI TOWN of Mammoth Lakes in math teacher dropped his car off at a Mammoth auto shop even in the really cold winters common to the Northeast. California’s Eastern Sierra, the first snowfall of the for repairs. He was visiting the area for a summer climb- “The ice didn’t slow him down one bit,” Minto said. “I strug- ing vacation when the car blew a head gasket. The friends gled to keep up.” Greene loved to run, competing on the track year is usually a beautiful and joyous celebration. Greene was traveling with headed home as scheduled, and team in high school and running the Boston Marathon a few Greene planned to drive to Colorado to join other friends times as an adult. As the student speaker for his high school But for the family and friends of a missing for more climbing as soon as his car was ready. graduation, Greene urged his classmates to take chances. IPennsylvania man, the falling flakes in early October “I may have to spend the rest of my life here in Mam- “The time has come to fulfill our current goals and to set moth,” he texted to a friend as he got more and more frus- new ones to be conquered later,” he said in his speech. -

Stanford Alpine Club Journal, 1958

STANFORD ALPINE CLUB JOURNAL 1958 STANFORD, CALIFORNIA i-., r ' j , / mV « Club Officers 1956-57 John Harlin, President John Mathias, Vice President Karl Hufbauer, Secretary William Pope, Treasurer 1957-58 Michael Roberts, President Karl Hufbauer, Vice-President Sidney Whaley, Secretary- Ivan Weightman, Treasurer ADVISORY COUNCIL John Maling, Chairman Winslow Briggs Henry Kendall Hobey DeStaebler Journal Staff Michael Roberts, Editor Henry Kendall, Photography Sidney Whaley Lenore Lamb Contents First Ascent of the East Peak of Mount Logan 1 Out of My Journal (Peru, 1955) 10 Battle Range, 1957 28 The SAC Trans-Sierra Tour 40 Climbing Notes 51 frontispiece: Dave Sowles enroute El Cafitan Tree, Yosemite Valley. Photo by Henry Kendall Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following: Mr. Richard Keeble, printing consultant Badger Printing Co., Appleton, Wise., photographic plates, press work and binding. Miss Mary Vogel, Appleton, Wise., composition and printing of text. Fox River Paper Corporation, Appleton, Wise., paper for text and photographs. FIRST ASCENT OF THE EAST PEAK OF MOUNT LOGAN by GILBERT ROBERTS Mount Logon. North America's second highest peak at 19,850 feet, is also one of the world's largest mountain masses. Located in the wildest part of the St. Elias Range, it has seen little mountaineering activity. In 1925, the first ascent was accomplished by a route from the Ogilvie Glacier which gained the long ridge leading to the summit from King Col. This ascent had gone down as one of the great efforts in mountaineering history. McCarthy, Foster, Lambert, Carpe, Read, and Taylor ulti- mately reached the central summit after months of effort including the relaying of loads by dog sled in the long Yukon winter--a far cry from the age of the air drop. -

Norman Clyde: Legendary Mountain Man E Was a Loner, Totally at Home Thet Scales at Only 140 Pounds, Clyde’S in the Mountains’ Solitude

Friends of the Oviatt Library Spring/Summer 2011 One-of-a-kind Exhibition: Tony Gardner’s Swan Song ome came replace the original Sto view the materials, the sort Library’s rarely of thing that makes seen treasures. up a library’s Special Others came to hear Collections. the keynote speaker, Following Stephen Tabor of Tabor’s thought- the Huntington provoking com Library. But many ments the as long-time friends sembled dignitaries of the library, those and Library friends truly in the know, repaired to the came to honor the Tseng Family Gal Oviatt Library’s lery where, while multi-talented, long- savoring an enticing serving Curator of medley of crudi Special Collections, tés, they ogled an Tony Gardner, who eclectic assortment recently announced his retirement, era of printing, he noted, when er of unique, rare, one-of-a-kind and to ogle his latest, and perhaps rors were found or changes judged ephemera plus portions of some his last, creation for the Library— necessary, presses were stopped, of the Library’s smaller collections. an exhibit featuring unique gems changes were made, and printing Among the items Gardner opted to from the Library’s archives. But for resumed. But the error-bearing showcase in his ultimate exhibition whatever reason, they came; and pages were not discarded—paper were such singular treasures as: A none left disappointed. was much too precious for such hand-written, eyewitness account Tabor, Curator of Early Printed extravagance—and the result was of the 1881 gunfight between the Books at the Huntington, pro books, even from the same print Earps and Clantons at the OK vided an appropriate prelude for ing that differed in subtle ways. -

Gazetteer of Surface Waters of California

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTI8 SMITH, DIEECTOE WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 296 GAZETTEER OF SURFACE WATERS OF CALIFORNIA PART II. SAN JOAQUIN RIVER BASIN PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OP JOHN C. HOYT BY B. D. WOOD In cooperation with the State Water Commission and the Conservation Commission of the State of California WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1912 NOTE. A complete list of the gaging stations maintained in the San Joaquin River basin from 1888 to July 1, 1912, is presented on pages 100-102. 2 GAZETTEER OF SURFACE WATERS IN SAN JOAQUIN RIYER BASIN, CALIFORNIA. By B. D. WOOD. INTRODUCTION. This gazetteer is the second of a series of reports on the* surf ace waters of California prepared by the United States Geological Survey under cooperative agreement with the State of California as repre sented by the State Conservation Commission, George C. Pardee, chairman; Francis Cuttle; and J. P. Baumgartner, and by the State Water Commission, Hiram W. Johnson, governor; Charles D. Marx, chairman; S. C. Graham; Harold T. Powers; and W. F. McClure. Louis R. Glavis is secretary of both commissions. The reports are to be published as Water-Supply Papers 295 to 300 and will bear the fol lowing titles: 295. Gazetteer of surface waters of California, Part I, Sacramento River basin. 296. Gazetteer of surface waters of California, Part II, San Joaquin River basin. 297. Gazetteer of surface waters of California, Part III, Great Basin and Pacific coast streams. 298. Water resources of California, Part I, Stream measurements in the Sacramento River basin. -

Sierra Vista Scenic Byway Sierra National Forest

Sierra Vista Scenic Byway Sierra National Forest WELCOME pute. Travel six miles south on Italian Bar Road Located in the Sierra National Forest, the Sierra (Rd.225) to visit the marker. Vista Scenic Byway is a designated member of the National Scenic Byway System. The entire route REDINGER OVERLOOK (3320’) meanders along National Forest roads, from North Outstanding view can be seen of Redinger Lake, the Fork to the exit point on Highway 41 past Nelder San Joaquin River and the surrounding rugged Sierra Grove, and without stopping takes about five hours front country. This area of the San Joaquin River to drive. drainage provides a winter home for the San Joaquin deer herd. Deer move out of this area in the hot dry The Byway is a seasonal route as forest roads are summer months and mi grate to higher country to blocked by snow and roads are not plowed or main- find food and water. tained during winter months. The Byway is gener- ally open from June through October. Call ahead to ROSS CABIN (4000’) check road and weather conditions. The Ross Cabin was built in the late 1860s by Jessie Blakey Ross and is one of the oldest standing log Following are some features along the route start- cabins in the area. The log cabin displays various de- ing at the Ranger Station in North Fork, proceeding signs in foundation construction and log assembly up the Minarets road north to the Beasore Road, brought to the west, exemplifying the pioneer spirit then south to Cold Springs summit, west to Fresno and technology of the mid-nineteenth century. -

Devils Postpile and the Mammoth Lakes Sierra Devils Postpile Formation and Talus

Nature and History on the Sierra Crest: Devils Postpile and the Mammoth Lakes Sierra Devils Postpile formation and talus. (Devils Postpile National Monument Image Collection) Nature and History on the Sierra Crest Devils Postpile and the Mammoth Lakes Sierra Christopher E. Johnson Historian, PWRO–Seattle National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 2013 Production Project Manager Paul C. Anagnostopoulos Copyeditor Heather Miller Composition Windfall Software Photographs Credit given with each caption Printer Government Printing Office Published by the United States National Park Service, Pacific West Regional Office, Seattle, Washington. Printed on acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America. 10987654321 As the Nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural and cultural resources. This includes fostering sound use of our land and water resources; protecting our fish, wildlife, and biological diversity; preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places; and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The Department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to ensure that their development is in the best interests of all our people by encouraging stewardship and citizen participation in their care. The Department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in island territories under U.S. administration. -

Three Early Influences

ROYAL ROBBINS Three Early Influences In April 2004 Royal Robbins took up an invitationfrom Terry Gifford to speak at the International Festival ofMountain Literature, Bretton Hall, about hisfavourite American climbing authors. Restricting himself to those writing prior to 1960, he assembled an impressivepack that included Charles Houston, Bob Bates, Alien Steck and Brad Washburn. His top three, however, were as follows, in reverse order. James Ramsey Ullman is not known for a string of first ascents, nor for the difficulty of the climbs he made. He was, primarily, not a climber but a writer. He earned his bread with words. He wrote fiction and non-fiction about other subjects as well as climbing, but, in my opinion, his one book that stands out, like Everest above the lesser peaks of his other works, is his story of mountaineering titled High Conquest. While discussing this book with Nick Clinch, I was surprised and delighted to hear him describe it as 'the Bible of our generation'. I had never talked to anyone else who had read it. It hadn't been recommended to me. I came across it by chance in the Los Angeles Public Library when, as a IS-year old, I was casually looking for mountaineering titles. It changed my life. This book, published in 1943, in the middle of the Second World War, attempts, in Ullman's words, 'to offer a word of suggestion and encouragement to the reader who would follow the Mountain Way himself'. The 'Mountain Way'! What an idea. I was ready for that way and High Conquest was just the kick in the pants to get me off and running. -

Forest Order 05-04-50-21-05 Inyo National Forest Food and Refuse

Forest Order 05-04-50-21-05 Inyo National Forest '-==USDA Food and Refuse Storage Restriction Areas Exhibit B Hoover Wilderness ..----=-- Ansel Adams Wilderness .......:�:;:::::::... White Mountains Wilderness John Muir Wilderness egend ,-� Inyo National Forest .....,,,,;;,,.,---r--, South Sierra Wilderness Inyo NF Wilderenss: Bear resistant cantainers required 10 20 Inyo NF Wilderness: bear resistant containers or counterbalance required Miles South Lake 05-04-50-21 -05 Treasure Lakes Trail Cloudripper Mount Gilbert Bishop Pass Trail Mount Johnson Mt. Agassiz 05-04-50-21-05 Mount Langley Cottonwood Lake 6 Hidden Lake Owens Point Sequoia Nat’l Park Wonoga Peak 11,240 ‘ Peak Cottonwood Pass Cottonwood Lakes Pacific Crest Trailhead (start) Trail Cottonwood Pass Trailhead Red Peak 05-04-50-21-05 11,568’ unnamed peak Mammoth Crest Duck Lake Peak Duck Lake Pacific Crest Trail Mount Mendenhall John Muir Trail Purple Lake Trail Lake Virginia Trail 11,160’ unnamed peak 10,760’ unnamed peak 10,080’ unnamed peak 05-04-50-21-05 See Exhibit I, Mammoth Lakes Devil’s Postpile NM King Creek Trail Reds Creek Mammoth Pass Granite Stairway Mammoth Crest Lion Point Crater Creek Trail Pumice Butte Fish Creek Island Crossing Unnamed Sequoia Nat’l Park Nat’l Sequoia 05-04-50-21-05 Golden Trout Creek Kearsarge Pass Trail Big Pothole Lake Gilbert Lake Matlock Lake Trail Bench Lake University Peak 05-04-50-21-05 Mono Pass Mack Lake Trail Mono Pass Little Lakes Valley Trail Ruby Lake Mount Morgan Mount Mills Morgan Pass Trail Lower Morgan Lake 12,744’ Bear Creek Spire 05-04-21-05 Koip Peak DonohueWaugh Lake Agnew Lake John Muir/PCT Trail Rodger Peak Thousand Yosemite IslandThousand Lake Island Pacific Crest Nat’l Park Lake Trail Banner Peak ShadowRitter Lake Peak Minaret Trail Devil’s Postpile NM Iron Mountain King Creek Trail See Exhibit F, Fish Creek Granite Stairway 05-04-50-21-05 North Fork, Lone Pine Creek Thor Peak Mt. -

Street Name AP Book Even Odd Abbey Drive

CITY OF CHICO STREET ADDRESS INDEX Master Street Address Guide (Street Names and Addresses Within City Limits) Updated - 10/02/20 Street Name A.P. Book Even Odd Abbey Drive (P) (street only) 42-51 no addresses no addresses Abbott Circle 6-80 all all Acacia Lane 45-53 all all Acorn Circle 6-08 all all Adlar Court (P) 42-66 all all Admiral Lane 16-05 all all Ahwahnee Commons (P) 18-31 all all Airpark Boulevard 47-55 all all Airport Service Road 47-55 all all Alameda Park Circle 18-15 all all Alamere Falls 16-45, 47 all all Alamo Avenue 42 all all Alan Lane 45-43 all all Alba Avenue 7-54 all all Albion Court 16-15 all all Alcott Avenue 2-69 all all Alden Court 15-18 all all Alder Street 4-32, 35, 39, 40, 44 all all Aldrin Court 45-38 all all Algonkin Avenue 3-59 all all Alice Lane 45-51 all all Allie Court 16-27 all all Allie Mae Court (P) 45-41 all all (P) Denotes Private Street K:\Addressing\Street Name Approvals\Street Address Index CDD - 10/2/2020 Page 1 of 55 Street Name A.P. Book Even Odd Almandor Circle 15-30 all all Almendia Court 42-41 all all Almendia Drive 42-40 ,41 all all Almond Street 4-50 all all Almond Vista Court (P) 42-64 all all Alpine Street 2-05, 41 all all Alynn Way 7-01,02 all all Amanda Way 2-11, 67 all all Amanecida Common (P) 18-35, 36 all all Amber Way 45-52 all all Amber Grove Drive 6-50 100 - 150 no addresses Ambrose Hill Drive (street only) 6-74 no addresses no addresses Anna Court 2-44 all all Antelope Creek Avenue 6-69, 84, 86 all all Anza Way (P) 7-24 all all Arbutus Avenue 3-24, 45, 49, 52, 53 all all Arcadian Avenue 3-01, 02, 03, 06, 09, 57, 61 all all Arch Way 16-13, 33 all all Archer Avenue 4-51 1014 no addresses Ardendale Way 18-39 all all Arena Way (Bidwell Park, street only) 16-17 no addresses no addresses Arizona Way 16-44 all all Arlington Drive 15-46 all all Arminta Court 2-05 all all Arroyo Way 6-09 all all (P) Denotes Private Street K:\Addressing\Street Name Approvals\Street Address Index CDD - 10/2/2020 Page 2 of 55 Street Name A.P. -

Clyde Minaret

CLYDE MINARET The Sierra Nevada Southeast Face 5.8 By Robert “SP” Parker The Minarets, Clyde Minaret is the tallest. photo: Todd Vogel Introduction Southeast Face - CLYDE MINARET L The Minarets area is Lookout Mountain To The Minarets From The Trailhead © Rockfax 2004 one of the most beau- 8,352 ft O Clyde Minaret San Joaquin N tiful in the High Sierra. river bridge Southeast Face 5.8 E Green tinged metamor- Olaine Mammoth Little Antelope 8,900 ft Middle Fork of San Lake Joaquin River Agnew Meadows Valley P phic rocks interlayered Campground and Scenic Loop 8,000 ft Agnew I with quartz glean and Trailhead Shadow Creek Meadows N 8,200 ft Shadow Lake River Trail Campgrounds sparkle amongst P E Minaret and rushing creeks and The Minarets end of Trailhead 12, 281 ft Summit Road 395 maintained trail Rosalie Lake B scented pine forests. FS Entrance WARMING Ediza Lake ANSELL Station WALL P I This is a popular hiking ADAMS 9,270 ft S 203 Cabin Lake destination but the WILDERNESS SKI AREA 8,200 ft H O climber is also drawn to 11.053ft 203 Agnew Devils Postpile Lake Mary Mammoth Meadow P Road the jagged peaks of the National Monument Sotcher Lake Lakes Minaret Crest. Readily 7,800 ft O Hot Spring W visible from Highway Red's Meadow Iceburg E 395 and from the lifts of HORSESHOE Lake 10,000 ft N SLABS Lake Mary S the Mammoth Mountain BEAR CRAG DIKE WALL Ski area the south face The Minarets Cecile Clyde Minaret R 3 mile CRYSTAL CRAG © Rockfax 2004 10,500 ft of Clyde Minaret domi- Lake Southeast Face 5.8 I V nates the area and from a distance appears steep and blank.