Three Early Influences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Matthew Greene Were Starting to Understand the Grave the Following Day

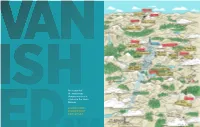

VANISHED An account of the mysterious disappearance of a climber in the Sierra Nevada BY MONICA PRELLE ILLUSTRATIONS BY BRETT AFFRUNTI CLIMBING.COM — 61 VANISHED Three months earlier in July, the 39-year-old high school feasted on their arms. They went hiking together often, N THE SMALL SKI TOWN of Mammoth Lakes in math teacher dropped his car off at a Mammoth auto shop even in the really cold winters common to the Northeast. California’s Eastern Sierra, the first snowfall of the for repairs. He was visiting the area for a summer climb- “The ice didn’t slow him down one bit,” Minto said. “I strug- ing vacation when the car blew a head gasket. The friends gled to keep up.” Greene loved to run, competing on the track year is usually a beautiful and joyous celebration. Greene was traveling with headed home as scheduled, and team in high school and running the Boston Marathon a few Greene planned to drive to Colorado to join other friends times as an adult. As the student speaker for his high school But for the family and friends of a missing for more climbing as soon as his car was ready. graduation, Greene urged his classmates to take chances. IPennsylvania man, the falling flakes in early October “I may have to spend the rest of my life here in Mam- “The time has come to fulfill our current goals and to set moth,” he texted to a friend as he got more and more frus- new ones to be conquered later,” he said in his speech. -

Sierra Vista Scenic Byway Sierra National Forest

Sierra Vista Scenic Byway Sierra National Forest WELCOME pute. Travel six miles south on Italian Bar Road Located in the Sierra National Forest, the Sierra (Rd.225) to visit the marker. Vista Scenic Byway is a designated member of the National Scenic Byway System. The entire route REDINGER OVERLOOK (3320’) meanders along National Forest roads, from North Outstanding view can be seen of Redinger Lake, the Fork to the exit point on Highway 41 past Nelder San Joaquin River and the surrounding rugged Sierra Grove, and without stopping takes about five hours front country. This area of the San Joaquin River to drive. drainage provides a winter home for the San Joaquin deer herd. Deer move out of this area in the hot dry The Byway is a seasonal route as forest roads are summer months and mi grate to higher country to blocked by snow and roads are not plowed or main- find food and water. tained during winter months. The Byway is gener- ally open from June through October. Call ahead to ROSS CABIN (4000’) check road and weather conditions. The Ross Cabin was built in the late 1860s by Jessie Blakey Ross and is one of the oldest standing log Following are some features along the route start- cabins in the area. The log cabin displays various de- ing at the Ranger Station in North Fork, proceeding signs in foundation construction and log assembly up the Minarets road north to the Beasore Road, brought to the west, exemplifying the pioneer spirit then south to Cold Springs summit, west to Fresno and technology of the mid-nineteenth century. -

Devils Postpile and the Mammoth Lakes Sierra Devils Postpile Formation and Talus

Nature and History on the Sierra Crest: Devils Postpile and the Mammoth Lakes Sierra Devils Postpile formation and talus. (Devils Postpile National Monument Image Collection) Nature and History on the Sierra Crest Devils Postpile and the Mammoth Lakes Sierra Christopher E. Johnson Historian, PWRO–Seattle National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 2013 Production Project Manager Paul C. Anagnostopoulos Copyeditor Heather Miller Composition Windfall Software Photographs Credit given with each caption Printer Government Printing Office Published by the United States National Park Service, Pacific West Regional Office, Seattle, Washington. Printed on acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America. 10987654321 As the Nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural and cultural resources. This includes fostering sound use of our land and water resources; protecting our fish, wildlife, and biological diversity; preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places; and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The Department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to ensure that their development is in the best interests of all our people by encouraging stewardship and citizen participation in their care. The Department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in island territories under U.S. administration. -

Ansel Adams Wilderness Bass Lake Ranger District

PACIFIC SOUTHWEST REGION Restoring, Enhancing and Sustaining Forests in California, Hawaii and the Pacific Islands Sierra National Forest Ansel Adams Wilderness Bass Lake Ranger District The Ansel Adams Wilderness is a diverse and Southern portions of the Wilderness provide forests spectacular area comprised of 228,500 acres of huge pine and fir where few people visit. draped along the crest of the Sierra Nevada Highway 41 and 168 access western slope trail- within the Sierra and Inyo National Forests. This heads while Highways 120 (Tioga Pass through Yo- wilderness ecosystem includes a number of lake semite National Park) and Highway 395 access trail- and stream systems that are the headwaters of the heads on the East side of the Sierra. San Joaquin River. Vegetation is mixed conifer- Commercial pack stations provide services from ous and deciduous forests of pine and oak in low Agnew and Reds Meadow (Inyo National Forest) on elevation, and sub-alpine forests of lodgepole the eastern side of the range, and from Miller pine, mountain hemlock and red fir. Alpine Meadow and Florence and Edison Lakes (Sierra Na- meadows grace the higher elevations with wild- tional Forest) on the western slope. flowers and crystal streams. Elevations range from hot dry canyons at REGULATIONS AND PERMIT REQUIRE- 3,500 feet in the San Joaquin River gorge to MENTS 13,157 foot Mount Ritter. Precipitation is from A wilderness Visitor Permit is required for all over- 18 to 50 inches, with snow depth averages about night trips into the wilderness. Important travel in- 171 inches. formation is available concerning bear encounters, The John Muir Trail, which starts in Yosem- fire danger, current weather, snow and hazard condi- ite National Park, crosses Donahue Pass (11,056 tions, and to assist visitors in understanding how to feet), into the Ansel Adams Wilderness and south properly use the wilderness and leave no trace. -

California Trail W R O MOUNTAINS H P I S Mount Jefferson Ive S SALMON MONTANA CORVALLIS E R M L E 10497Ft S E L MOUNTAINS a DILLON Orn 25 Er WISC

B DALLAS S La Creole Creek R N E tte S ALEM I N O A B OZEMAN B ILLINGS e Y V r S T. PAUL C om plex m A WALLOWA 90 ive r MINNEAPOLIS 94 T N E R e la Y l N A ello iv M i SALMON RIVER R w sto n e iss U C R issip California Trail W r O M O U N TA IN S H p i S Mount Jefferson ive M S S ALMON MONTANA C OR VALLIS E R L E 10497ft s E L MOUNTAINS A DILLON orn 25 er WISC. te U E B igh iv Designated routes of the E Mary’s River Crossing 3200m u B L H D EA R TO O B R h TH M r California National Historic Trail sc M TS e G e d Riv D B AK ER O ow er G Long Tom River Crossing McC ALL U N P Additional routes T A SOUTH DAKOTA M INNESOTA N A I B B N N I S G S HER IDAN B e 29 90 S A H lle Scale varies in this north-looking EUGENE Jo Fourc he River A BEND h n Da R O perspective view spanning about A y River R Yellowstone O R 35 1,500 miles (2,400 km) from east N C loud Peak PIER R E B orah Peak Lake K to west. Topography derives from Pleasant 5 13187ft R R 12662ft A C ODY GREYBULL M GTOPO30 digital elevation data. -

The John Muir Newsletter, Winter 1996/97

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons John Muir Newsletters John Muir Papers Winter 12-1-1996 The ohnJ Muir Newsletter, Winter 1996/97 The ohnJ Muir Center for Regional Studies Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/jmn Part of the American Studies Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation The oJ hn Muir Center for Regional Studies, "The oJ hn Muir Newsletter, Winter 1996/97" (1996). John Muir Newsletters. 48. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/jmn/48 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the John Muir Papers at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in John Muir Newsletters by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. N E W TER <*)o JoHN MuiR <4¢:> l)' WI[ 'N· T • i '\ . l.'Nl I . - '•I') ~.Jo ..t ' \~ 1)\. \·V .. j_ l ~ ~~~t/li~J); by Shayne Zurilgen :;;ti+''•;\<;r '{Editor's note: The author, a senior in geology at the ·.,···:.'~:r:.<:t·•.:.s •}:- .. ' :,• ·;, •. 1;?i1;t/•:\:./·.'ljhiversity of the Pacific, prepared this paper in the fall developing intellectual pursuits but rather seemed to feel that anything but hard physical work was a distraction from God's :!';(;:;:. <J('.;~l,'';•6fi996 for an undergraduate history class, "John Muir plan. Muir believed strongly in God but felt more tribute was t/1.;c;'jti~·)r;;,:,'?i6d the Environment. '') paid to Him amidst His works in nature than in the confines of a church constructed by humans. After nearly losing an eye in a Sj~-: d Lord Tennyson was looking into his microscope one day machine shop accident that temporarily blinded him, he left . -

The Sierra Club Pictorial Collections at the Bancroft Library Call Number Varies

The Sierra Club Pictorial Collections at The Bancroft Library Call Number Varies Chiefly: BANC PIC 1971.031 through BANC PIC 1971.038 and BANC PIC 1971.073 through 1971.120 The Bancroft Library U.C. Berkeley This is a DRAFT collection guide. It may contain errors. Some materials may be unavailable. Draft guides might refer to material whose location is not confirmed. Direct questions and requests to [email protected] Preliminary listing only. Contents unverified. Direct questions about availability to [email protected] The Sierra Club Pictorial Collections at The Bancroft Library Sierra Club Wilderness Cards - Series 1 BANC PIC 1971.026.001 ca. 24 items. DATES: 19xx Item list may be available at library COMPILER: Sierra Club DONOR: SIZE: PROVENANCE: GENERAL NOTE No Storage Locations: 1971.026.001--A Sierra Club Wilderness Cards - Series 1 24 items Index Terms: Places Represented Drakes Bay (Calif.) --A Echo Park, Dinosaur National Monument (Colo.) --A Northern Cascades (Wash.) --A Point Reyes (Calif.) --A Sawtooth Valley (Idaho) --A Sequoia National Forest (Calif.) --A Volcanic Cascades (Or.) --A Waldo Lake (Or.) --A Wind River (Wyo.) --A Photographer Blaisdell, Lee --A Bradley, Harold C. --A Brooks, Dick --A Douglas, Larry --A Faulconer,DRAFT Philip W. --A Heald, Weldon Fairbanks, 1901-1967 --A Hessey, Charles --A Hyde, Philip --A Litton, Martin --A Riley, James --A Simons, David R., (David Ralph) --A Tepfer, Sanford A. --A Warth, John --A Worth, Don --A Wright, Cedric --A Page 1 of 435 Preliminary listing only. Contents unverified. Direct questions about availability to [email protected] The Sierra Club Pictorial Collections at The Bancroft Library "Discover our outdoors" BANC PIC 1971.026.002 ca. -

The Historical Distribution of Bighorn Sheep in the Sierra Nevada, California

Summer 2014 417 California Fish and Game 100(3):417-435; 2014 The historical distribution of bighorn sheep in the Sierra Nevada, California JOHN D. WEHAUSEN* AND FRED L. JONES White Mountain Research Center, University of California, 3000 East Line Street, Bishop, CA 93514, USA (JDW) 1721 Grouse Ridge Trail, Cool, CA 95614, USA (FLJ) *Correspondent: [email protected] Bighorn sheep in the Sierra Nevada disappeared from most of their historic range, surviving in only 3 populations west of the town of Independence in the Owens Valley. As a primary basis for restoration of these sheep, we compiled historical sightings and skull remains for Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep by twelve geographic regions, along with early estimates of population sizes where they existed. Historic sightings suggest that at least 10 populations survived to the twentieth century of which 2 persisted to the middle of that century before disappearing; but the sighting record does not distinguish viable populations from those that may have been declining to extinction. While it is possible for some populations to assign a decade when they disappeared, those populations may have lost viability earlier. Our data base probably represents the historical north-south distribution of these sheep and provides distributional details for some populations. However, it is remarkably sparse for some regions, suggesting that it may not have captured the full historical distribution of this animal, particularly west of the Sierra crest, where the earliest population losses may have occurred. Restoration efforts need to recognize this potential shortcoming. Key words: bighorn sheep, endangered species, historical distribution, Ovis canadensis sierrae, Sierra Nevada _________________________________________________________________________ Information on historical distribution is an important foundation for wildlife restoration programs. -

Nature and History on the Sierra Crest: Devils Postpile and the Mammoth Lakes Sierra Devils Postpile Formation and Talus

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Devils Postpile National Monument California Nature and History on the Sierra Crest Devils Postpile and the Mammoth Lakes Sierra Christopher E. Johnson Historian, PWRO–Seattle Nature and History on the Sierra Crest: Devils Postpile and the Mammoth Lakes Sierra Devils Postpile formation and talus. (Devils Postpile National Monument Image Collection) Nature and History on the Sierra Crest Devils Postpile and the Mammoth Lakes Sierra Christopher E. Johnson Historian, PWRO–Seattle National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 2013 Production Project Manager Paul C. Anagnostopoulos Copyeditor Heather Miller Composition Windfall Software Photographs Credit given with each caption Printer Government Printing Office Published by the United States National Park Service, Pacific West Regional Office, Seattle, Washington. Printed on acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America. 10987654321 As the Nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural and cultural resources. This includes fostering sound use of our land and water resources; protecting our fish, wildlife, and biological diversity; preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places; and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The Department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to ensure that their development is in the best interests of all our people by encouraging stewardship and citizen participation in their care. The Department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in island territories under U.S. -

China Lake Mountain Rescue Group Talus Pile May 2004

CHINA LAKE MOUNTAIN RESCUE GROUP TALUS PILE MAY 2004 NUMBER 131 TRAINING SCHEDULE May 10 Mon Meeting Huey, Finco, Bishop May 12 Wed Stretcher Hut night Training committee May 15-16 Sat-Sun Stretcher practice Training committee May 21-24 Fri-Mon Barnard and Heller Hinman May 29-31 Sat-Mon Morgan and Stanford Rockwell Jun 4-6 Fri-Sun Kern Peak C. Burge Jun 14 Mon Meeting Hinman, D. Burge, Runkle Jun 8-9 Tue-Wed Summer class Jun 12-13 Sat-Sun Goode, Peak 13040 Rockwell Jun 15-16 Tue-Wed Summer class Jun 18-20 Fri-Sun Whitney East Buttress Runkle Jun 22-23 Tue-Wed Summer class Jun 26-27 Sat-Sun Lone Pine Peak, NE Ridge Bishop Jun 29-30 Tue-Wed Summer class Jul 2-4 Fri-Sat Whitney Basin traverse Rockwell Jul 10-11 Sat-Sun Summer class day trips Jul 12 Mon Meeting Botham, Breitenstein, Green Jul 13-14 Tue-Wed Summer class Jul 16-18 Fri-Sun Whitney Trail 100th Celebration Rockwell Jul 20-21 Tue-Wed Summer class Jul 24-25 Sat-Sun Summer class overnights Jul 27 Tue Summer class Jul 28 Wed Summer class party Jul 30-Aug 1 Fri-Sun Open Aug 7-15 Sat-Sun Kaweahs Hinman Aug 13-15 Fri-Sun Merriam and Royce (Pine Creek Pass) C. Burge Aug 19-24 Thu-Tue Granite Peak, Montana Huey Aug 21-22 Sat-Sun Open Aug 23 Mon Summer party Aug 29-31 Sun-Tue Fishook Arete Runkle Sep 4-6 Sat-Mon Tuolumne Meadows Finco OPERATION REPORTS 2003-03 5-8 August 2003 Search Sawtooths, Mono County Daryl Hinman On July 30, 2003, 46-year-old Fred Claasen of Livermore, California began a 6-day backpack trip from Mono Village at Twin Lakes in Mono County, California. -

![[Pdf] John Muir Trail Topographic Map Guide (National Geographic Trails Illustrated Map) National Geographic Maps - Pdf Free Book](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1705/pdf-john-muir-trail-topographic-map-guide-national-geographic-trails-illustrated-map-national-geographic-maps-pdf-free-book-7351705.webp)

[Pdf] John Muir Trail Topographic Map Guide (National Geographic Trails Illustrated Map) National Geographic Maps - Pdf Free Book

[Pdf] John Muir Trail Topographic Map Guide (National Geographic Trails Illustrated Map) National Geographic Maps - pdf free book John Muir Trail Topographic Map Guide (National Geographic Trails Illustrated Map) Ebooks, John Muir Trail Topographic Map Guide (National Geographic Trails Illustrated Map) Books Online, free online John Muir Trail Topographic Map Guide (National Geographic Trails Illustrated Map), John Muir Trail Topographic Map Guide (National Geographic Trails Illustrated Map) PDF, John Muir Trail Topographic Map Guide (National Geographic Trails Illustrated Map) Ebooks Free, Read John Muir Trail Topographic Map Guide (National Geographic Trails Illustrated Map) Online Free, Download John Muir Trail Topographic Map Guide (National Geographic Trails Illustrated Map) E-Books, Free Download John Muir Trail Topographic Map Guide (National Geographic Trails Illustrated Map) Full Popular National Geographic Maps, Download PDF John Muir Trail Topographic Map Guide (National Geographic Trails Illustrated Map) Free Online, Free Download John Muir Trail Topographic Map Guide (National Geographic Trails Illustrated Map) Full Version National Geographic Maps, John Muir Trail Topographic Map Guide (National Geographic Trails Illustrated Map) Ebooks Free, John Muir Trail Topographic Map Guide (National Geographic Trails Illustrated Map) pdf read online, book pdf John Muir Trail Topographic Map Guide (National Geographic Trails Illustrated Map), free online John Muir Trail Topographic Map Guide (National Geographic Trails Illustrated Map), -

The Sierra Sampler

The Sierra Sampler Listed below, by region, are the 100 peaks that comprise the Sierra Sampler. While no mountain in the Sierra can be climbed without time, effort, and risk, these peaks represent a sub-set of the full SPS List that are relatively easy to get to, pose less danger than others on the List, are fun to climb and/or hold other qualities, and are drawn from the main areas of the range. The Sampler, which has been approved by the SPS Management Committee, thus provides a good introduction to the Sierra for climbers of varying degrees of experience and ability. The only award or acknowledgement associated with the completion of the Sierra Sampler is your satisfaction and enjoyment. Enjoy! 1. SOUTHERN 2. MINERAL KING 3. OLANCHA TO 4. CORCORAN TO SIERRA-5 AND KERN RIVER-4 LANGLEY & WEST-4 WHITNEY-5 Owens Peak Kern Peak ** OLANCHA PEAK Mount Mallory Lamont Peak Vandever Mountain Muah Mountain Mount Irvine Sawtooth Peak (S) Florence Peak Cirque Peak **MOUNT WHITNEY Rockhouse Peak Sawtooth Peak (N) Mount Langley Thor Peak Sirretta Peak Lone Pine Peak 6. KAWEAHS AND 5. WHITNEY TO WEST-5 7. GREAT WESTERN DIVIDE-2 8. KINGS KERN WILLIAMSON-4 Alta Peak DIVIDE-2 Mount Silliman South Guard Mount Young Eagle Scout Peak ** MOUNT BREWER *Mount Ericsson Mount Hale Mount Stewart Center Peak Mount Carillon **MOUNT KAWEAH **MT WILLIAMSON 11. WESTERN MID- 12. SOUTH SIERRA-5 10. BAXTER PASS PALISADES-4 *Mount Ruskin To TABOOSE PASS-3 **SPLIT MOUNTAIN 9. KEARSARGE Kennedy Mountain Birch Mountain PASS VICINITY-6 Colosseum Mountain Mount Harrington The Thumb Striped Mountain *Tehipite Dome *University Peak *Middle Palisade Independence Peak Cardinal Mountain Three Sisters Mount Gould 16.