“Exploration of the Sierra Nevada” (1925) by Francis P. Farquhar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sequoia-Kings Canyon National Parks, However, Went Unnoticed

• D -1:>K 1.2!;EQUOJA-KING$ Ci\NYON NATIONAL PARKS History of the Parks "''' Evaluation of Historic Resources Detennination of Effect, DCP Prepared by • A. Berle Clemensen DENVER SERVICE CENTER HISTORIC PRESERVATION TEA.'! NATIONAL PAP.K SERVICE UNITED STATES DEPAR'J'}fENT OF THE l~TERIOR DENVER, COLOR..\DO SEPTEffilER 1975 i i• Pl.EA5!: RETUl1" TO: B&WScans TEallillCAL INFORMAl!tll CfNIEil 0 ·l'i «coo,;- OOIVER Sf:RV!Gf Cf!fT£R llAT!ONAL PARK S.:.'Ma j , • BRIEF HISTORY OF SEQUOIA Spanish and Mexican Period The first white men, the Spanish, entered the San Joaquin Valley in 1772. They, however, only observed the Sierra Nevada mountains. None entered the high terrain where the giant Sequoia exist. Only one explorer came close to the Sierra Nevadas. In 1806 Ensign Gabriel Moraga, venturing into the foothills, crossed and named the Rio de la Santos Reyes (River of the Holy Kings) or Kings River. Americans in the San Joaquin Valley The first band of Americans entered the Valley in 1827 when Jedediah Smith and a group of fur traders traversed it from south to north. This journey ushered in the first American frontier as fifteen years of fur trapping followed. Still, none of these men reported sighting the giant trees. It was not until 1833 that members of the Joseph R. 1lalker expedition crossed the Sierra Nevadas and received credit as the first whites to See the Sequoia trees. These trees are presumed to form part of either the present M"rced or Tuolwnregroves. Others did not learn of their find since Walker's group failed to report their discovery. -

WPLI Resolution

Matters from Staff Agenda Item # 17 Board of County Commissioners ‐ Staff Report Meeting Date: 11/13/2018 Presenter: Alyssa Watkins Submitting Dept: Administration Subject: Consideration of Approval of WPLI Resolution Statement / Purpose: Consideration of a resolution proclaiming conservation principles for US Forest Service Lands in Teton County as a final recommendation of the Wyoming Public Lands Initiative (WPLI) process. Background / Description (Pros & Cons): In 2015, the Wyoming County Commissioners Association (WCCA) established the Wyoming Public Lands Initiative (WPLI) to develop a proposed management recommendation for the Wilderness Study Areas (WSAs) in Wyoming, and where possible, pursue other public land management issues and opportunities affecting Wyoming’s landscape. In 2016, Teton County elected to participate in the WPLI process and appointed a 21‐person Advisory Committee to consider the Shoal Creek and Palisades WSAs. Committee meetings were facilitated by the Ruckelshaus Institute (a division of the University of Wyoming’s Haub School of Environment and Natural Resources). Ultimately the Committee submitted a number of proposals, at varying times, to the BCC for consideration. Although none of the formal proposals submitted by the Teton County WPLI Committee were advanced by the Board of County Commissioners, the Board did formally move to recognize the common ground established in each of the Committee’s original three proposals as presented on August 20, 2018. The related motion stated that the Board chose to recognize as a resolution or as part of its WPLI recommendation, that all members of the WPLI advisory committee unanimously agree that within the Teton County public lands, protection of wildlife is a priority and that there would be no new roads, no new timber harvest except where necessary to support healthy forest initiatives, no new mineral extraction excepting gravel, no oil and gas exploration or development. -

Geological Sukvey

DEPABTMENT OF THE IHTERIOE BULLETIN OF THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SUKVEY No. 148 WASHINGTON' G-OVEKNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1897 UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SUEYEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, 'DIRECTOR ANALYSES OF ROCKS ANALYTICAL METHODS LABORATORY OF THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY 1880 to 1896 BY F. W. CLAEKE AND W. F. HILLEBEAND WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1897 CONTENTS. Pago. Introduction, by F. W. Clarke ....'.......................................... 9 Some principles and methods of analysis applied to silicate rocks; by W. F. Hillebrand................................................................ 15 Part I. Introduction ................................................... 15 Scope of the present paper .......................................... 20 Part II. Discussion of methods ..................................i....... 22 Preparation of sample....................:.......................... 22 Specific gravity. ............................: ......--.........--... 23 Weights of sample to be employed for analysis....................... 26 Water, hygroscopic ................................ ................. 26 Water, total or combined....... ^.................................... 30 Silica, alumina, iron, etc............................................ 34 Manganese, nickel, cobalt, copper, zinc.............................. 41 Calcium and strontium...................................... ........ 43 Magnesium......................................................... 43 Barium and titanium............... .... ............................ -

Frontier Fighters and the Romance of the Ranchos By, Jim Stebinger Mr

Newsletter of the Jedediah Smith Society • University of the Pacific, Stockton, California SUMMER 2020 Jedediah Smith in Popular Culture: Frontier Fighters and The Romance of The Ranchos By, Jim Stebinger Mr. Stebinger is a freelance writer, journalist and amateur historian living in Los Angeles. As a UCLA graduate he has had a lifelong interest in history with a focus on western expansion, Jedediah Smith and the mountain fur trade. One of the great surprises of the internet is the extent to up the Missouri. which people will work, research, publish and upload The men go huge amounts of material without recompense. Of course to Ashley’s Wikipedia is the prime example but of perhaps more “mansion” to immediate interest to members of the Society has been the enlist. uploading of vast amounts of “Classic Radio” including at On May 20, least two radio biographies of Jedediah Smith. 1823 we hear raging battle The first piece, which runs 15 minutes 10 seconds, was the “near the present sixth episode of a 39 part series called “Frontier Fighters” 1 boundary of that briefly depicted the lives of men (and some women) North and central to the westward expansion of the United States. South Dakota” Frontier Fighters dramatized soldiers, explorers, mountain Between the men, bankers, doctors and some famous battles including Ashley party the fall of the Alamo. The subjects chosen lived or the events and an enemy occurred from before the founding of the United States up identified as “Arickarees.” Smith is tending to the wounded to about 1900. Although the series is easily available for when Ashley calls for a volunteer to seek aid from Andrew download little is known of the production and crew. -

Page 78 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 45A–1 Kaweah River and The

§ 45a–1 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION Page 78 Kaweah River and the headwaters of that branch Fork Kaweah River to its junction with Cactus of Little Kern River known as Pecks Canyon; Creek; thence easterly along the first hydro- thence southerly and easterly along the crest of graphic divide south of Cactus Creek to its the hydrographic divide between Pecks Canyon intersection with the present west boundary of and Soda Creek to its intersection with a lateral Sequoia National Park, being the west line of divide at approximately the east line of section township 16 south, range 29 east; thence south- 2, township 19 south, range 31 east; thence erly along said west boundary to the southwest northeasterly along said lateral divide to its corner of said township; thence easterly along intersection with the township line near the the present boundary of Sequoia National Park, southeast corner of township 18 south, range 31 being the north line of township 17 south, range east of the Mount Diablo base and meridian; 29 east, to the northeast corner of said township; thence north approximately thirty-five degrees thence southerly along the present boundary of west to the summit of the butte next north of Sequoia National Park, being the west lines of Soda Creek (United States Geological Survey al- townships 17 and 18 south, range 30 east, to the titude eight thousand eight hundred and eighty- place of beginning; and all of those lands lying eight feet); thence northerly and northwesterly within the boundary line above described are in- along the crest of the hydrographic divide to a cluded in and made a part of the Roosevelt-Se- junction with the crest of the main hydro- quoia National Park; and all of those lands ex- graphic divide between the headwaters of the cluded from the present Sequoia National Park South Fork of the Kaweah River and the head- are included in and made a part of the Sequoia waters of Little Kern River; thence northerly National Forest, subject to all laws and regula- along said divide now between Horse and Cow tions applicable to the national forests. -

Inyo National Forest Visitor Guide

>>> >>> Inyo National Forest >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> Visitor Guide >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> $1.00 Suggested Donation FRED RICHTER Inspiring Destinations © Inyo National Forest Facts “Inyo” is a Paiute xtending 165 miles Bound ary Peak, South Si er ra, lakes and 1,100 miles of streams Indian word meaning along the California/ White Mountain, and Owens River that provide habitat for golden, ENevada border between Headwaters wildernesses. Devils brook, brown and rainbow trout. “Dwelling Place of Los Angeles and Reno, the Inyo Postpile Nation al Mon ument, Mam moth Mountain Ski Area National Forest, established May ad min is tered by the National Park becomes a sum mer destination for the Great Spirit.” 25, 1907, in cludes over two million Ser vice, is also located within the mountain bike en thu si asts as they acres of pris tine lakes, fragile Inyo Na tion al For est in the Reds ride the chal leng ing Ka mi ka ze Contents Trail from the top of the 11,053-foot mead ows, wind ing streams, rugged Mead ow area west of Mam moth Wildlife 2 Sierra Ne va da peaks and arid Great Lakes. In addition, the Inyo is home high Mam moth Moun tain or one of Basin moun tains. El e va tions range to the tallest peak in the low er 48 the many other trails that transect Wildflowers 3 from 3,900 to 14,494 feet, pro vid states, Mt. Whitney (14,494 feet) the front coun try of the forest. Wilderness 4-5 ing diverse habitats that sup port and is adjacent to the lowest point Sixty-five trailheads provide Regional Map - North 6 vegetation patterns ranging from in North America at Badwater in ac cess to over 1,200 miles of trail Mono Lake 7 semiarid deserts to high al pine Death Val ley Nation al Park (282 in the 1.2 million acres of wil der- meadows. -

Snow Hydrology with Dr

Snow Hydrology with Dr. Ned Bair Ologies Podcast January 14, 2019 Oh hey, it’s that blueberry bagel that tastes like onions ‘cause it pressed its face into an everything bagel. Alie Ward, back with another episode of Ologies. It’s the middle of January, and here in the northern hemisphere, lips are chapped, feet are cold, parkas are on. I’m here to give you a snow job. But first, thank you to everyone who supports on Patreon, and who gets merch, including the new black t-shirts (yes!) at OlogiesMerch.com. Of course, thanks to everyone who rates and subscribes, who leaves reviews on iTunes, you know I read them. You know I read them. For example, this week, thank you to Evie, who said, In the hopes of Alie noticing me [heeyyy], I gotta say that this podcast just recently got me through some pretty bad flying anxiety. So thank you. Thank you for taking me into the sky with you, Evie. Also, EvanDK, I hope you and your pops are feeling okay. Okay, so: snow. Snow! Not just snow, but big cold crumbly scary dangerous avalanches. What the hell are they? I searched far and wide for a snow expert, and I connected with a dude who got his Ph.D. in Environmental Science and Management from University of California, Santa Barbara, a place Steven Ray Morris and I both attended, but this guy is primarily based up near Mammoth Mountain, which is technically a giant lava dome complex. Freakin’ volcano, near Yosemite. It’s chill. -

Tulare County Measure R Riparian-Wildlife Corridor Report

Tulare County Measure R Riparian-Wildlife Corridor Report Prepared by Tulare Basin Wildlife Partners for Tulare County Association of Govenments 11 February 2008 Executive Summary As part of an agreement with the Tulare County Association of Governments, Tulare Basin Wildlife Partners (TBWP) visited nine potential riparian and wildlife corridors in Tulare County during summer 2007. We developed a numerical ranking system and determined the five corridors with highest potential for conservation, recreation and conjunctive uses. The selected corridors include: Deer Creek Riparian Corridor, Kings River Riparian Corridor, Oaks to Tules Riparian Corridor, Lewis Creek Riparian Corridor, and Cottonwood Creek Wildlife Corridor. For each corridor, we provide a brief description and a summary of attributes and opportunities. Opportunities include flood control, groundwater recharge, recreation, tourism, and wildlife. We also provide a brief description of opportunities for an additional eight corridors that were not addressed in depth in this document. In addition, we list the Measure R transportation improvements and briefly discuss the potential wildlife impacts for each of the projects. The document concludes with an examination of other regional planning efforts that include Tulare County, including the San Joaquin Valley Blueprint, the Tulare County Bike Path Plan, the TBWP’s Sand Ridge-Tulare Lake Plan, the Kaweah Delta Water Conservation District Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP), and the USFWS Upland Species Recovery Plan. Tulare Basin Wildlife Partners, 2/11/2008 Page 2 of 30 Table of Contents Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………. 4 Goals and Objectives………………………...……………………………………………. 4 Tulare County Corridors……………………..……………………………………………. 5 Rankings………………………………………………………………………….. 5 Corridors selected for Detailed Study…………………………………………….. 5 Deer Creek Corridor………………………………………………………. 5 Kings River Corridor……………………………………………………… 8 Oaks to Tules Corridor…………………………………..………………… 10 Lewis Creek East of Lindsay……………………………………………… 12 Cottonwood Creek………………………………………...………………. -

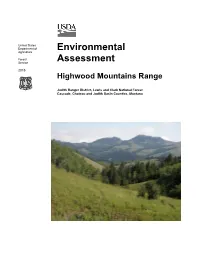

Highwood Mountains Range Analysis Project Area on Those Resources Affected by Implementation

United States Department of Agriculture Environmental Forest Service Assessment 2015 Highwood Mountains Range Judith Ranger District, Lewis and Clark National Forest Cascade, Choteau and Judith Basin Counties, Montana For More Information Contact: Lewis and Clark National Forest Judith Ranger District Standford, Montana www.fs.fed.us/r1/lewisclark/projects 406-566-2292. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW., Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TTY). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Environmental Assessment Table of Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................4 Location of the Proposed Project Area ..........................................................................................................4 -

Matthew Greene Were Starting to Understand the Grave the Following Day

VANISHED An account of the mysterious disappearance of a climber in the Sierra Nevada BY MONICA PRELLE ILLUSTRATIONS BY BRETT AFFRUNTI CLIMBING.COM — 61 VANISHED Three months earlier in July, the 39-year-old high school feasted on their arms. They went hiking together often, N THE SMALL SKI TOWN of Mammoth Lakes in math teacher dropped his car off at a Mammoth auto shop even in the really cold winters common to the Northeast. California’s Eastern Sierra, the first snowfall of the for repairs. He was visiting the area for a summer climb- “The ice didn’t slow him down one bit,” Minto said. “I strug- ing vacation when the car blew a head gasket. The friends gled to keep up.” Greene loved to run, competing on the track year is usually a beautiful and joyous celebration. Greene was traveling with headed home as scheduled, and team in high school and running the Boston Marathon a few Greene planned to drive to Colorado to join other friends times as an adult. As the student speaker for his high school But for the family and friends of a missing for more climbing as soon as his car was ready. graduation, Greene urged his classmates to take chances. IPennsylvania man, the falling flakes in early October “I may have to spend the rest of my life here in Mam- “The time has come to fulfill our current goals and to set moth,” he texted to a friend as he got more and more frus- new ones to be conquered later,” he said in his speech. -

Frontispiece the 1864 Field Party of the California Geological Survey

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U. S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC ROAD GUIDE TO KINGS CANYON AND SEQUOIA NATIONAL PARKS, CENTRAL SIERRA NEVADA, CALIFORNIA By James G. Moore, Warren J. Nokleberg, and Thomas W. Sisson* Open-File Report 94-650 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. * Menlo Park, CA 94025 Frontispiece The 1864 field party of the California Geological Survey. From left to right: James T. Gardiner, Richard D. Cotter, William H. Brewer, and Clarence King. INTRODUCTION This field trip guide includes road logs for the three principal roadways on the west slope of the Sierra Nevada that are adjacent to, or pass through, parts of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks (Figs. 1,2, 3). The roads include State Route 180 from Fresno to Cedar Grove in Kings Canyon Park (the Kings Canyon Highway), State Route 198 from Visalia to Sequoia Park ending near Grant Grove (the Generals Highway) and the Mineral King road (county route 375) from State Route 198 near Three Rivers to Mineral King. These roads provide a good overview of this part of the Sierra Nevada which lies in the middle of a 250 km span over which no roads completely cross the range. The Kings Canyon highway penetrates about three-quarters of the distance across the range and the State Route 198~Mineral King road traverses about one-half the distance (Figs. -

Triangulation in Utah 1871-1934

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Harold L. Ickes, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. C. Mendenhall, Director Bulletin 913 TRIANGULATION IN UTAH 1871-1934 J. G. STAACK Chief Topographic Engineer UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1940 Tor sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price 20 cents (paper) CONTENTS Page Introduction ______________________________________________________ 1 Scope of report------__-_-_---_----_------------ --__---__ _ 1 Precision __ _ ________________________ _ __________________ _ ___ 1 Instruments used._ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 2 Station marks___- _ _.__ __ __ _ 2 Datum_-_-_-__ __________________________ ______ ______-___.__ 3 Methods of readjustment..._____.-.__..________.___._._...___.__ 4 Form of results__-.________________________ _.___-_____.______ 5 Arrangement__.______________________________ _ ___ _ ________ 6 Descriptions of stations._______________________________________ 6 Azimuths and distances.__ ____-_.._---_--_________ -____ __ __ ^ 7 Maps.__----__-----_-_---__-_--_-___-_-___-__-__-_-_-___.-.__ 7 Personnel_ _ __-----_-_-_---_---------_--__-____-__-_.--_.___ . 7 Projects 9 Uinta Forest Reserve, 1897-98_ 9 Cottonwood and Park City special quadrangles, 1903____ _ 19 Iron Springs special quadrangle, 1905____________________________ 22 Northeastern Utah, 1909.. -_. 26 Eastern Utah, 1910 - . 30 Logan quadrangle, 1913._________-__-__'_--______-___:_____.____ 42 Uintah County, 1913___-__. 48 Eastern Utah, 1914.. ... _ _ .. 55 Northern Utah, 1915 (Hodgeson)_____-___ __-___-_-_-__-_--. _. 58 Northern Utah, 1915 <Urquhart)_.