Stanford Alpine Club Journal, 1958

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plate Tectonics, Volcanoes, and Earthquakes / Edited by John P

ISBN 978-1-61530-106-5 Published in 2011 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.) in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC 29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010. Copyright © 2011 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved. Rosen Educational Services materials copyright © 2011 Rosen Educational Services, LLC. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services. For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932. First Edition Britannica Educational Publishing Michael I. Levy: Executive Editor J. E. Luebering: Senior Manager Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition John P. Rafferty: Associate Editor, Earth Sciences Rosen Educational Services Alexandra Hanson-Harding: Editor Nelson Sá: Art Director Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager Nicole Russo: Designer Matthew Cauli: Cover Design Introduction by Therese Shea Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Plate tectonics, volcanoes, and earthquakes / edited by John P. Rafferty. p. cm.—(Dynamic Earth) “In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.” Includes index. ISBN 978-1-61530-187-4 ( eBook) 1. Plate tectonics. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior » , • National Park Service V National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determination for individual properties and districts Sec instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" lor 'not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and area of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10- 900A). Use typewriter, word processor or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property____________________________________________________ historic name Camp 4 other name/site number Sunnyside Campground__________________________________________ 2. Location_______________________________________________________ street & number Northside Drive, Yosemite National Park |~1 not for publication city or town N/A [_xj vicinity state California code CA county Mariposa code 043 zip code 95389 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this Itjiomination _irquest for determination of eligibility meets the documentationsJand»ds-iJar -

Yosemite Guide Yosemite

Yosemite Guide Yosemite Where to Go and What to Do in Yosemite National Park July 29, 2015 - September 1, 2015 1, September - 2015 29, July Park National Yosemite in Do to What and Go to Where NPS Photo NPS 1904. Grove, Mariposa Monarch, Fallen the astride Soldiers” “Buffalo Cavalry 9th D, Troop Volume 40, Issue 6 Issue 40, Volume America Your Experience Yosemite, CA 95389 Yosemite, 577 PO Box Service Park National US DepartmentInterior of the Year-round Route: Valley Yosemite Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Upper Summer-only Routes: Yosemite Shuttle System El Capitan Fall Yosemite Shuttle Village Express Lower Shuttle Yosemite The Ansel Fall Adams l Medical Church Bowl i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area l T al Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System F e E1 5 P2 t i 4 m e 9 Campground os Mirror r Y 3 Uppe 6 10 2 Lake Parking Village Day-use Parking seasonal The Ahwahnee Half Dome Picnic Area 11 P1 1 8836 ft North 2693 m Camp 4 Yosemite E2 Housekeeping Pines Restroom 8 Lodge Lower 7 Chapel Camp Lodge Day-use Parking Pines Walk-In (Open May 22, 2015) Campground LeConte 18 Memorial 12 21 19 Lodge 17 13a 20 14 Swinging Campground Bridge Recreation 13b Reservations Rentals Curry 15 Village Upper Sentinel Village Day-use Parking Pines Beach E7 il Trailhead a r r T te Parking e n il i w M in r u d 16 o e Nature Center El Capitan F s lo c at Happy Isles Picnic Area Glacier Point E3 no shuttle service closed in winter Vernal 72I4 ft Fall 2I99 m l E4 Mist Trai Cathedral ail Tr op h Beach Lo or M ey ses erce all only d R V iver E6 Nevada To & Fall The Valley Visitor Shuttle operates from 7 am to 10 pm and serves stops in numerical order. -

Inyo National Forest Visitor Guide

>>> >>> Inyo National Forest >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> Visitor Guide >>> >>> >>> >>> >>> $1.00 Suggested Donation FRED RICHTER Inspiring Destinations © Inyo National Forest Facts “Inyo” is a Paiute xtending 165 miles Bound ary Peak, South Si er ra, lakes and 1,100 miles of streams Indian word meaning along the California/ White Mountain, and Owens River that provide habitat for golden, ENevada border between Headwaters wildernesses. Devils brook, brown and rainbow trout. “Dwelling Place of Los Angeles and Reno, the Inyo Postpile Nation al Mon ument, Mam moth Mountain Ski Area National Forest, established May ad min is tered by the National Park becomes a sum mer destination for the Great Spirit.” 25, 1907, in cludes over two million Ser vice, is also located within the mountain bike en thu si asts as they acres of pris tine lakes, fragile Inyo Na tion al For est in the Reds ride the chal leng ing Ka mi ka ze Contents Trail from the top of the 11,053-foot mead ows, wind ing streams, rugged Mead ow area west of Mam moth Wildlife 2 Sierra Ne va da peaks and arid Great Lakes. In addition, the Inyo is home high Mam moth Moun tain or one of Basin moun tains. El e va tions range to the tallest peak in the low er 48 the many other trails that transect Wildflowers 3 from 3,900 to 14,494 feet, pro vid states, Mt. Whitney (14,494 feet) the front coun try of the forest. Wilderness 4-5 ing diverse habitats that sup port and is adjacent to the lowest point Sixty-five trailheads provide Regional Map - North 6 vegetation patterns ranging from in North America at Badwater in ac cess to over 1,200 miles of trail Mono Lake 7 semiarid deserts to high al pine Death Val ley Nation al Park (282 in the 1.2 million acres of wil der- meadows. -

2020 January Scree

the SCREE Mountaineering Club of Alaska January 2020 Volume 63, Number 1 Contents Mount Anno Domini Peak 2330 and Far Out Peak Devils Paw North Taku Tower Randoism via Rosie’s Roost "The greatest danger for Berlin Wall most of us is not that our aim is too high and we Katmai and the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes miss it, but that it is too Peak of the Month: Old Snowy low and we reach it." – Michelangelo JANUARY MEETING: Wednesday, January 8, at 6:30 p.m. Luc Mehl will give the presentation. The Mountaineering Club of Alaska www.mtnclubak.org "To maintain, promote, and perpetuate the association of persons who are interested in promoting, sponsoring, im- proving, stimulating, and contributing to the exercise of skill and safety in the Art and Science of Mountaineering." This issue brought to you by: Editor—Steve Gruhn assisted by Dawn Munroe Hut Needs and Notes Cover Photo If you are headed to one of the MCA huts, please consult the Hut Gabe Hayden high on Devils Paw. Inventory and Needs on the website (http://www.mtnclubak.org/ Photo by Brette Harrington index.cfm/Huts/Hut-Inventory-and-Needs) or Greg Bragiel, MCA Huts Committee Chairman, at either [email protected] or (907) 350-5146 to see what needs to be taken to the huts or repaired. All JANUARY MEETING huts have tools and materials so that anyone can make basic re- Wednesday, January 8, at 6:30 p.m. at the BP Energy Center at pairs. Hutmeisters are needed for each hut: If you have a favorite 1014 Energy Court in Anchorage. -

Matthew Greene Were Starting to Understand the Grave the Following Day

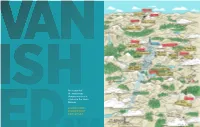

VANISHED An account of the mysterious disappearance of a climber in the Sierra Nevada BY MONICA PRELLE ILLUSTRATIONS BY BRETT AFFRUNTI CLIMBING.COM — 61 VANISHED Three months earlier in July, the 39-year-old high school feasted on their arms. They went hiking together often, N THE SMALL SKI TOWN of Mammoth Lakes in math teacher dropped his car off at a Mammoth auto shop even in the really cold winters common to the Northeast. California’s Eastern Sierra, the first snowfall of the for repairs. He was visiting the area for a summer climb- “The ice didn’t slow him down one bit,” Minto said. “I strug- ing vacation when the car blew a head gasket. The friends gled to keep up.” Greene loved to run, competing on the track year is usually a beautiful and joyous celebration. Greene was traveling with headed home as scheduled, and team in high school and running the Boston Marathon a few Greene planned to drive to Colorado to join other friends times as an adult. As the student speaker for his high school But for the family and friends of a missing for more climbing as soon as his car was ready. graduation, Greene urged his classmates to take chances. IPennsylvania man, the falling flakes in early October “I may have to spend the rest of my life here in Mam- “The time has come to fulfill our current goals and to set moth,” he texted to a friend as he got more and more frus- new ones to be conquered later,” he said in his speech. -

Harvard Mountaineering 3

HARVARD MOUNTAINEERING 1931·1932 THE HARVARD MOUNTAINEERING CLUB CAMBRIDGE, MASS. ~I I ' HARVARD MOUNTAINEERING 1931-1932 THE HARVARD MOUNTAINEERING CLUB CAMBRIDGE, MASS . THE ASCENT OF MOUNT FAIRWEATHER by ALLEN CARPE We were returning from the expedition to Mount Logan in 1925. Homeward bound, our ship throbbed lazily across the Gulf of Alaska toward Cape Spencer. Between reefs of low fog we saw the frozen monolith of St. Elias, rising as it were sheer out of the water, its foothills and the plain of the Malaspina Glacier hidden behind the visible sphere of the sea. Clouds shrouded the heights of the Fairweather Range as we entered Icy Strait and touched at Port Althorp for a cargo of salmon; but I felt then the challenge of this peak which was now perhaps the outstanding un climbed mOUlitain in America, lower but steeper than St. Elias, and standing closer to tidewater than any other summit of comparable height in the world. Dr. William Sargent Ladd proved a kindred spirit, and in the early summer of 1926 We two, with Andrew Taylor, made an attempt on the mountain. Favored by exceptional weather, we reached a height of 9,000 feet but turned back Photo by Bradford Washburn when a great cleft intervened between the but tresses we had climbed and the northwest ridge Mount Fairweather from the Coast Range at 2000 feet of the peak. Our base was Lituya Bay, a beau (Arrows mark 5000 and 9000-foot camps) tiful harbor twenty miles below Cape Fair- s camp at the base of the south face of Mount Fair weather; we were able to land near the foot of the r weather, at 5,000 feet. -

Canada's Everest? Rethinking the First Ascent of Mount Logan and the Politics of Nationhood, 1925

Scholarly Articles CANADA’S EVEREST? 95 Sport History Review, 2004, 35, 95-121 © 2004 Human Kinetics Publishers, Inc. Canada’s Everest? Rethinking the First Ascent of Mount Logan and the Politics of Nationhood, 1925 Zac Robinson and PearlAnn Reichwein University of Alberta In the early decades of the twentieth century, Canadian mountain- eering progressed largely independently of the European mainstream. During this era, however, one British endeavour captured the imagination of North American climbers and, for the first time, propelled mountaineer- ing into western popular culture: the struggle that began in the early 1920s to climb the highest mountain in the world, Mount Everest (8,852 m). Being able to claim the first ascent of Mt. Everest was of paramount impor- tance to Britain, a preoccupation that lasted nearly half a century. After two earlier unsuccessful attempts, the British made a third attempt in 1924 via the mountain’s north ridge. All hopes were resting on George Leigh Mallory—the so-called “Gallahad” of the British mountaineering· fraternity—and his young, inexperienced climbing partner, Andrew Irvine. Clad in tweed suits and puttees, the two men left for the summit on the morning of June 8 but never returned. News of the death of Mallory and Irvine deeply moved many people in the West, with one editorial reflect- ing nationalistically: In the days of peace, England will always hold some who are not content with humdrum routine and soft living. The spirit, which ani- mated the attacks on Everest, is the same as that which has prompted arctic and other expeditions, and in earlier times led to the formation of the Empire itself. -

Superintendent's Message

Superintendent’s Message Welcome! I am so grateful to have you here to help caretake Yosemite during these unprecedented circumstances. Thank you for your commitment to public service and public land during this challenging time. On behalf of the leadership team, we are deeply honored to have you as part of our world-class team. While not new to the park, I began here as the Acting Superintendent this past January. I’ve spent my career in the park service and most recently came from Point Reyes National Seashore where I’ve been superintendent since 2010. I have always been inspired at every opportunity to work with Yosemite’s passionate and talented staff and my experience since January has only underscored this sentiment. My vision for Yosemite in Summer 2020 is first and foremost to ensure the safety of our staff and visitors. Our physical and mental health are Commented [KN1]: I would say here something like, “I critical to our success as a park. We live closely with each other and with the dynamic natural landscape, both of have been impressed by the speak up culture here at which require us to be uniquely aware and resilient. I fully encourage each and every one of you to take Yosemite. If you ever feel unsafe in the task you are given, advantage of the support services available to you as an employee with the understanding that daily peer support please be sure to speak up and let your supervisor know.” is the most effective strategy benefitting us at individual and organizational levels. -

Ar Study of Oceanic and Continental Deformation Processes During An

A(40)Ar/(39) Ar study of oceanic and continental deformation processes during an oblique collision: Taconian orogeny in the Quebec reentrant of the Canadian Appalachians Michel Malo, Gilles Ruffet, Alix Pincivy, Alain Tremblay To cite this version: Michel Malo, Gilles Ruffet, Alix Pincivy, Alain Tremblay. A(40)Ar/(39) Ar study of oceanic and continental deformation processes during an oblique collision: Taconian orogeny in the Quebec reen- trant of the Canadian Appalachians. Tectonics, American Geophysical Union (AGU), 2008, 27 (4), pp.TC4001. 10.1029/2006TC002094. insu-00322674 HAL Id: insu-00322674 https://hal-insu.archives-ouvertes.fr/insu-00322674 Submitted on 29 Jun 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. TECTONICS, VOL. 27, TC4001, doi:10.1029/2006TC002094, 2008 A 40Ar/39Ar study of oceanic and continental deformation processes during an oblique collision: Taconian orogeny in the Quebec reentrant of the Canadian Appalachians Michel Malo,1 Gilles Ruffet,2 Alix Pincivy,1 and Alain Tremblay3 Received 7 December 2006; revised 9 January 2008; accepted 10 March 2008; published 1 July 2008. [1] Two phases of penetrative deformation are Stockmal et al., 1987; Malo et al., 1995; van Staal et documented in the Taconian hinterland of the al., 1998], particularly for the Ordovician Taconian orogeny Appalachian orogen in the Gaspe´ Peninsula. -

Mountaineer AMC February 2014 ARIZONA MOUNTAINEERING CLUB Arizonamountaineeringclub.Org the Mace in Sedona Story & Cover Photo: Murthy Tata Page 11

The Arizona Mountaineer AMC February 2014 ARIZONA MOUNTAINEERING CLUB arizonamountaineeringclub.org The Mace in Sedona Story & Cover Photo: Murthy Tata Page 11 Frank Vers jumps from the main spire on the Mace The Arizona Mountaineering Club BOARD OF DIRECTORS President ............................................. Bill Fallon .............................................................602-909-8889 Vice-President ..................................... John Gray ............................................................480-363-3248 Secretary ............................................. Erik Filsinger ................................................. [email protected] Treasurer ............................................. Thad Colgrove .....................................................602-795-2167 Director-2 ............................................. Mike Lust ................................................ [email protected] Director-2 ............................................. Cheryl Beaver ........................................ [email protected] Director-2 ............................................. Douglas Matson [email protected] Director-2 ............................................. Gavin Storey [email protected] Director-1 ............................................. David Arthur Sampson [email protected] COMMITTEES Advanced Rock Climbing .................. David Arthur Sampson [email protected] -

1967, Al and Frances Randall and Ramona Hammerly

The Mountaineer I L � I The Mountaineer 1968 Cover photo: Mt. Baker from Table Mt. Bob and Ira Spring Entered as second-class matter, April 8, 1922, at Post Office, Seattle, Wash., under the Act of March 3, 1879. Published monthly and semi-monthly during March and April by The Mountaineers, P.O. Box 122, Seattle, Washington, 98111. Clubroom is at 719Y2 Pike Street, Seattle. Subscription price monthly Bulletin and Annual, $5.00 per year. The Mountaineers To explore and study the mountains, forests, and watercourses of the Northwest; To gather into permanent form the history and traditions of this region; To preserve by the encouragement of protective legislation or otherwise the natural beauty of North west America; To make expeditions into these regions m fulfill ment of the above purposes; To encourage a spirit of good fellowship among all lovers of outdoor life. EDITORIAL STAFF Betty Manning, Editor, Geraldine Chybinski, Margaret Fickeisen, Kay Oelhizer, Alice Thorn Material and photographs should be submitted to The Mountaineers, P.O. Box 122, Seattle, Washington 98111, before November 1, 1968, for consideration. Photographs must be 5x7 glossy prints, bearing caption and photographer's name on back. The Mountaineer Climbing Code A climbing party of three is the minimum, unless adequate support is available who have knowledge that the climb is in progress. On crevassed glaciers, two rope teams are recommended. Carry at all times the clothing, food and equipment necessary. Rope up on all exposed places and for all glacier travel. Keep the party together, and obey the leader or majority rule. Never climb beyond your ability and knowledge.