Clyde Minaret

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Matthew Greene Were Starting to Understand the Grave the Following Day

VANISHED An account of the mysterious disappearance of a climber in the Sierra Nevada BY MONICA PRELLE ILLUSTRATIONS BY BRETT AFFRUNTI CLIMBING.COM — 61 VANISHED Three months earlier in July, the 39-year-old high school feasted on their arms. They went hiking together often, N THE SMALL SKI TOWN of Mammoth Lakes in math teacher dropped his car off at a Mammoth auto shop even in the really cold winters common to the Northeast. California’s Eastern Sierra, the first snowfall of the for repairs. He was visiting the area for a summer climb- “The ice didn’t slow him down one bit,” Minto said. “I strug- ing vacation when the car blew a head gasket. The friends gled to keep up.” Greene loved to run, competing on the track year is usually a beautiful and joyous celebration. Greene was traveling with headed home as scheduled, and team in high school and running the Boston Marathon a few Greene planned to drive to Colorado to join other friends times as an adult. As the student speaker for his high school But for the family and friends of a missing for more climbing as soon as his car was ready. graduation, Greene urged his classmates to take chances. IPennsylvania man, the falling flakes in early October “I may have to spend the rest of my life here in Mam- “The time has come to fulfill our current goals and to set moth,” he texted to a friend as he got more and more frus- new ones to be conquered later,” he said in his speech. -

Wringing Light out of Stone

MOUNTAIN PROFILE THE PALISADES I DOUG ROBINSON Wringing Light out of Stone So this kid walks into the Palisades.... I was twenty, twenty-one—don’t remember. It was the mid-1960s, for sure. I’d been hanging in the Valley for a few seasons, wide-eyed and feeling lucky to be soaking up wisdom by holding the rope for Chuck Pratt, the finest crack climber of the Golden Age. Yeah, cracks: those stark highways up Yosemite’s smooth granite that only open up gradually to effort and humility. Later they begin to reveal another facet: shadowed, interior, drawing us toward hidden dimensions of our ascending passion. ¶ The Palisades, though, are alpine, which means they are even more fractured. It would take me a little longer to cut through to the true dimensions of even the obvious features. To my young imagination, they looked like the gleaming, angular granite in the too-perfect romantic pictures that I devoured out of Gaston Rébuffat’s mountaineering books. My earliest climbing partner, John Fischer, had already been there— crampons lashed to his tan canvas-and-leather pack—and he’d returned, wide-eyed, with the tale of having survived a starlit bivy on North Palisade. [Facing Page] Don Jensen climbing in the Palisades, Sierra Nevada, California, during the 1960s—captured in a photo that reflects the atmosphere of the French alpinist Gaston Rébuffat’s iconic images of the Alps. Many consider the Palisades to be the most alpine region of the High Sierra, although climate change has begun to affect the classic ice and snow climbs. -

Nature and History on the Sierra Crest: Devils Postpile and the Mammoth Lakes Sierra Devils Postpile Formation and Talus

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Devils Postpile National Monument California Nature and History on the Sierra Crest Devils Postpile and the Mammoth Lakes Sierra Christopher E. Johnson Historian, PWRO–Seattle Nature and History on the Sierra Crest: Devils Postpile and the Mammoth Lakes Sierra Devils Postpile formation and talus. (Devils Postpile National Monument Image Collection) Nature and History on the Sierra Crest Devils Postpile and the Mammoth Lakes Sierra Christopher E. Johnson Historian, PWRO–Seattle National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 2013 Production Project Manager Paul C. Anagnostopoulos Copyeditor Heather Miller Composition Windfall Software Photographs Credit given with each caption Printer Government Printing Office Published by the United States National Park Service, Pacific West Regional Office, Seattle, Washington. Printed on acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America. 10987654321 As the Nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural and cultural resources. This includes fostering sound use of our land and water resources; protecting our fish, wildlife, and biological diversity; preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places; and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The Department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to ensure that their development is in the best interests of all our people by encouraging stewardship and citizen participation in their care. The Department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in island territories under U.S. -

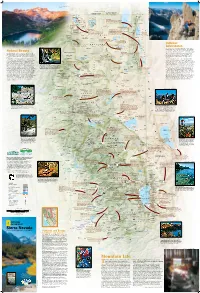

Sierra Nevada’S Endless Landforms Are Playgrounds for to Admire the Clear Fragile Shards

SIERRA BUTTES AND LOWER SARDINE LAKE RICH REID Longitude West 121° of Greenwich FREMONT-WINEMA OREGON NATIONAL FOREST S JOSH MILLER PHOTOGRAPHY E E Renner Lake 42° Hatfield 42° Kalina 139 Mt. Bidwell N K WWII VALOR Los 8290 ft IN THE PACIFIC ETulelake K t 2527 m Carr Butte 5482 ft . N.M. N. r B E E 1671 m F i Dalton C d Tuber k Goose Obsidian Mines w . w Cow Head o I CLIMBING THE NORTHEAST RIDGE OF BEAR CREEK SPIRE E Will Visit any of four obsidian mines—Pink Lady, Lassen e Tule Homestead E l Lake Stronghold l Creek Rainbow, Obsidian Needles, and Middle Fork Lake Lake TULE LAKE C ENewell Clear Lake Davis Creek—and take in the startling colors and r shapes of this dense, glass-like lava rock. With the . NATIONAL WILDLIFE ECopic Reservoir L proper permit you can even excavate some yourself. a A EM CLEAR LAKE s EFort Bidwell REFUGE E IG s Liskey R NATIONAL WILDLIFE e A n N Y T REFUGE C A E T r W MODOC R K . Y A B Kandra I Blue Mt. 5750 ft L B T Y S 1753 m Emigrant Trails Scenic Byway R NATIONAL o S T C l LAVA E Lava ows, canyons, farmland, and N E e Y Cornell U N s A vestiges of routes trod by early O FOREST BEDS I W C C C Y S B settlers and gold miners. 5582 ft r B K WILDERNESS Y . C C W 1701 m Surprise Valley Hot Springs I Double Head Mt. -

1956 , the Mountaineer Organized 1906 • Incorporated 1913

The M_ 0 U NTA I N E E R SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 1906 CJifty Qoulen Years of ctl([ountaineering 1956 , The Mountaineer Organized 1906 • Incorporated 1913 Volume 50 December 28, 1956 Number 1 Boa KOEHLER Editor in Chief MORDA SLAUSON Assistant Editor MARJORIE WILSON Assistant Editor SHIRLEY EASTMAN Editorial Assistant JOAN ASTELL Everett Branch Editor BRUNI WISLICENUS Tacoma Branch Editor IRENE HINKLE Membership Editor I,, � Credits: Robert N. Latz, J climbing adviser; Mrs. Irving Gavett, clubroom custodian (engravings) ; Elenor Bus well, membership; Nicole Desme, advertising. Published monthly, January to November· inclusive, and semi monthly during December by THE MOUNTAINEERS, Inc., P. 0. Box 122, Seattle 11, Wash. (Clubrooms, 523 Pike St., Se attle.) Subscription Price: $2 yearly. Entered as second class matter, April 18, 1922, at Post Of fice in Seattle, Wash., under the Act of March 3, 1879. Copyright 1956 by THE MOUNTAINEERS, Inc. Photo: Shadow Creek Falls by Antonio Gamero. Confents I E A FoR.WORD-hy Paul W. Wiseman__________________________________________________________________________ 5 History" 1906 THE FrnsT TwE 'TY-YEARS 1930-by Joseph T. H<izard_ ________________:____________________ 6 1931 THESECOND TwE 'TY-FIVE YEARS 1956-by Arthur R. Winder________________________ 14 1909 THE EvERETT BRANCH 1956-by Joan Astell ------------------------------------------------- 21 1912 THE TACOMA BRANCH 1956-by Keith D. Goodman---------------------------------------- 23 A WORD PORTRAIT OF EDMONDS. MEA 'Y-by Lydia Love,·ing Forsyth ______________________ 26 MEANY: A PoEM-by A. H. Albertson ..------------------ --------------------------------------------------- 32 FLEETING GLIMP ES OF EDMOND S. MEANY-by Ben C. Mooers------------------------------ 33 FrnsT SUMMER OUTING: THE OLYMPICS, 1907-by L. A. Nelson-----------------�--------- 34 EARLY Oun Gs THROUGH THE EYES OF A GIRL-by Mollie Leckenby King------------ 36 JOHN Mum's AscE T OF MOUNT RAINIER (AS RECORDED BY HIS PHOTOGRAPHER A. -

Mammoth Area

Excerpt from Geologic Trips, Sierra Nevada by Ted Konigsmark ISBN 0-9661316-5-7 GeoPress All rights reserved. No part ofthis book may be reproduced without written permission, except for critical articles or reviews. For other geologic trips see: www.geologictrips.com 92 - Trip 2. MAMMOTH AREA Hot Creek Gorge Mono Lake Hilton Creek Fault Bishop Tuff Mammoth Mountain Lee Vining Earthquake Fault 120 Devils Postpile Minaret Summit M Inyo Craters o n 120 o C r 10 Miles a t e r s June Lake I n G y la o ss M C o r un a t ta e in r Long Valley Caldera s S ie r ra Resurgent Dome 203 Crowley 395 Lake Mammoth H i l Lakes t Toms Place o n C r e e Nevada k f Volcanic domes, a u l craters and flows t Fault - 93 Trip 2 MAMMOTH AREA Volcanoes, Domes and Craters The Mammoth area is one of the most volcanically active areas in the lower 48 States. From Bishop to Mono Lake, you are never out of sight of volcanoes, domes, craters, fumaroles, hot springs, and many different types of volcanic rocks, including rhyolite, andesite, basalt, obsidian, pumice, tuff, and welded tuff. During this trip, you’ll see examples of all of these volcanic features and volcanic rocks. Much of this volcanic activity is associated with the Long Valley Caldera, the remains of a huge volcano that erupted 760,000 years ago. Most of the remaining volcanic activity is associated with the Inyo and Mono Craters, a trend of domes and craters that extend from the Long Valley Caldera north to Mono Lake. -

The Sierra Club's Changing Attitude Toward Roadbuilding

ABSTRACT Title of Document: TO RENDER INACCESSIBLE: THE SIERRA CLUB'S CHANGING ATTITUDE TOWARD ROADBUILDING Jason Henry Schultz, Master of Arts, History, 2008 Directed by: Professor Thomas Zeller, Department of History In the early twentieth century, the Sierra Club was a foremost booster of roads and national parks as a way of rendering the mountains accessible. In the middle of the twentieth century, however, the Club reassessed this stance. By looking at three instances where the Club initially supported roads and recreational projects in California's Sierra Nevada—improvement of the Tioga Road, support for a Minaret Summit Highway, and development of Mineral King for skiing—I trace the Club's movement from an organization promoting automobile-oriented recreation to a group opposed to the development of recreation facilities, including roads. These Sierran struggles broaden the importance of the definition of wilderness as roadlessness investigated by Paul Sutter, and demonstrate that such visible concerns over roads persisted beyond the interwar years. TO RENDER INACCESSIBLE: THE SIERRA CLUB'S CHANGING ATTITUDE TOWARD ROADBUILDING By Jason Henry Schultz Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, History 2008 Advisory Committee: Professor Thomas Zeller, Chair Professor Robert D. Friedel Professor David B. Sicilia © Copyright by Jason Henry Schultz 2008 Table of Contents List of Figures............................................................................................................iv -

Middle Cretaceous Ash-Flow Tuff and Caldera-Collapse Deposit in the Minarets Caldera, East-Central Sierra Nevada, California

Middle Cretaceous ash-flow tuff and caldera-collapse deposit in the Minarets Caldera, east-central Sierra Nevada, California R. S. FISKE Department of Mineral Sciences, Smithsonian Institution, NHB-119, Washington, D.C. 20560 O. T. TOBISCH Earth Science Board, University of California, Santa Cruz, California 95064 ABSTRACT areas in the Ritter Range Pendant, east-central Sierra Nevada, is un- derlain by a thick and massive sequence of metavolcanic rocks no- A 2.3-km section of ash-flow tuff and associated caldera-collapse ticeably less deformed than those immediately to the east. Fiske and deposit, representing the extrusive facies of part of the Sierra Nevada Tobisch (1978) interpreted these rocks to be remnants of a caldera-fill batholith, is totally exposed from its floor to its top in the Minarets complex deposited in what they called the Minarets Caldera. Later Caldera, east-central Sierra Nevada. Rapid burial and subsequent work by us, reported here, clarifies basic stratigraphic relations in this hornblende hornfels facies metamorphism resulted in remarkable pres- complex. ervation of primary textures and structures, despite the development of The rocks of the Minarets Caldera are noteworthy because they cleavage domains in parts of the caldera fill; late Tertiary uplift and provide a superbly exposed record of large-scale caldera formation Quaternary erosion have produced a rugged terrain where every meter coeval with mid-Cretaceous volcanism in the east-central Sierra Ne- of section is available for study. Large-scale caldera-filling eruption of vada. The caldera rocks have yielded mid-Cretaceous radiometric ash-flow tuff was interrupted by emplacement of a wedge-shaped mass ages (Table 1, samples 1-3), suggesting that they may be genetically of caldera-collapse deposit as much as 2 km thick, whose volume ex- related to nearby granitoids of the Shaver, Buena Vista, and Merced ceeded 70 km3. -

Mineral Resources of the Minarets Wilderness and Adjacent Areas, Madera and Mono Counties, California

STUDIES RELATED TO WILDERNESS WILDERNESS AREAS Mineral Resources of the Minarets Wilderness and Adjacent Areas, Madera and Mono Counties, California By U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY and U.S. BUREAU OF MINES A. Regional Setting, Geology, and Geechemical Studies of the Minarets Wilderness and Adjacent Areas, Madera and Mono Counties, California By N. KING HUBER, U.S. GEOLOGICAL SuRVEY B. Geophysical Studies of the Minarets Wilderness and Adjacent Areas, Madera and Mono Counties, California By HOWARD W. OLIVER, U.S. GEOLOGICAL SuRVEY C. Geothermal-Resource Evaluation of the Minarets Wilderness and Adjacent Areas, Madera and Mono Counties, California By ROY A. BAILEY, U.S. GEOLOGICAL SuRVEY D. Economic-Mineral Appraisal of the Minarets Wilderness and Adjacent Areas, Madera and Mono Counties, California By HORACE K. THURBER, MICHAEL S. _MILLER, C. THOMAS HILLMAN, DAVIDS. LINDSEY, and RICHARD W. MORRIS, U.S. BUREAU OF MINES STUDIES RELATED TO WILDERNESS - WILDERNESS AREAS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1516-A-D An evaluation of the mineral potential of the area UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON 1982 • UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR JAMES G. WATT, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Mineral resources of the Minarets Wilderness and adjacent areas, Madera and Mono Counties, California. (Geological Survey bulletin ; 1516-A-D) Bibliography: p. 154-160 Supt. of Docs. no.: I 19.3:1516-A-D 1. Mines and mineral resources--California. I. United States. Geological Survey. II. United States. Bureau of Mines. ! III. Series: United States. Geological Survey. Bulletin 1516-A-D. QE75.B9 no. 1516-A-D 557.3s 81-607191 [TN24.C2J [553'09794'48] AACR2 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. -

Harvard Extension School – Capstone Project Journalism Graduate Program Advisor: Angelia Herrin May 15, 2015 Missing in Mammot

Harvard Extension School – Capstone Project Journalism Graduate Program Advisor: Angelia Herrin May 15, 2015 Missing in Mammoth By Monica Prelle Normally the first snowfall of the year is a beautiful and joyous celebration in Mammoth Lakes, a small ski town situated in California’s Eastern Sierra, but the early-October snow was disheartening for the searchers of a missing Pennsylvania man. Hope faded with the inevitable change in season, and the family and close friends of Matthew Greene started to understand the grave reality that he may never be found. Each was going through the motions of their daily lives, living in a tug-of- war between despair and optimism, and feeling helpless from across the country. On July 29, 2013, Matthew Greene was reported missing. A few weeks earlier, the 39-year-old high school math teacher dropped his car off at a Mammoth auto shop for repairs. He was in the area on a summer climbing vacation when the car blew a head gasket. The friends Greene was traveling with headed home as scheduled, and Greene planned to drive to Colorado to join other friends for more climbing as soon as his car was ready. Anxious to get on with his trip, Greene started to get mad that his car was taking so long to be fixed. “I may have to spend the rest of my life here in Mammoth,” he texted to a friend. At the time, Mammoth Lakes was experiencing characteristic sunshine and above average temperatures. No one has heard from Greene since he last talked to his parents on July 16, 2013. -

The Evolution of Search and Rescue in Yosemite National Park

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2007 Wilderness handrails: The evolution of search and rescue in Yosemite National Park Christopher Edward Johnson University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Johnson, Christopher Edward, "Wilderness handrails: The evolution of search and rescue in Yosemite National Park" (2007). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 2174. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/jqpk-bhrs This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WILDERNESS HANDRAILS: THE EVOLUTION OF SEARCH AND RESCUE IN YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK by Christopher Edward Johnson Bachelor of Arts California State University, Sacramento 2003 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in History Department of History College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas August 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1448406 Copyright 2007 by Johnson, Christopher Edward All rights reserved. -

Notes and Correspondence

Notes and Correspondence The Search for Walter Starr, Jr. On the evening of July 29, 1933 Walter A Starr Left San Francisco for a vacation trip in the High Sierra, starting out over the Tioga Road, destination not known. He had made a tentative plan to meet his father on August 7th at Glacier Lodge, near Big Pine, Inyo County, and when he did not arrive there, after waiting until August 9th, his father left for home with a feeling of anxiety, but with the conclusion that his son had perhaps changed his plans, and had decided not to come out to Glacier Lodge from the high mountain country. Starr was due to return home on August 13th, and when he did not make an appearance at his office on the morning of the 14th, his father became convinced that some serious accident must have befallen him. The first problem was to locate Starr's automobile. By noon a description of the car had been sent out through the State Police, Highway Patrol, Forest Rangers, and the Sheriffs of Mono and lnyo counties. Meanwhile Mr. Francis P. Farquhar, of the Sierra Club, had located several members of the club known for their ability as climbers and mountaineers, who, with great loyalty and unselfishness, held themselves in readiness to start on the search whenever the call should come. At about 7 o'clock that evening word was received that the car had been found at Agnew Meadow, thirteen miles over the pass from Mammoth, Mono County, and also that Starr's camp had been located near Lake Ediza, which lies under the east side of Mount Ritter.