From Archangels to Virtual Pilgrims: a Brief History of Papal Digital Mobilization As Soft Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

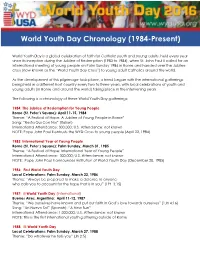

World Youth Day Chronology (1984-Present)

World Youth Day Chronology (1984-Present) World Youth Day is a global celebration of faith for Catholic youth and young adults, held every year since its inception during the Jubilee of Redemption (1983 to 1984), when St. John Paul II called for an international meeting of young people on Palm Sunday 1984 in Rome and handed over the Jubilee cross (now known as the “World Youth Day Cross”) to young adult Catholics around the world. As the development of this pilgrimage took place, a trend began with the international gatherings being held in a different host country every two to three years, with local celebrations of youth and young adults (in Rome and around the world) taking place in the intervening years. The following is a chronology of these World Youth Day gatherings: 1984: The Jubilee of Redemption for Young People Rome (St. Peter’s Square): April 11-15, 1984 Theme: “A Festival of Hope: A Jubilee of Young People in Rome” Song: “Resta Qui Con Noi” (Italian) International Attendance: 300,000; U.S. Attendance: not known NOTE: Pope John Paul II entrusts the WYD Cross to young people (April 22, 1984) 1985: International Year of Young People Rome (St. Peter’s Square): Palm Sunday, March 31, 1985 Theme: “A Festival of Hope: International Year of Young People” International Attendance: 300,000; U.S. Attendance: not known NOTE: Pope John Paul II announces institution of World Youth Day (December 20, 1985) 1986: First World Youth Day Local Celebrations: Palm Sunday, March 23, 1986 Theme: “Always be prepared to make a defense to anyone who calls you to account for the hope that is in you” (1Pt 3:15) 1987: II World Youth Day (International) Buenos Aires, Argentina: April 11-12, 1987 Theme: “We ourselves have known and put our faith in God’s love towards ourselves” (1Jn 4:16) Song: “Un Nuevo Sol” (Spanish): “A New Sun” International Attendance: 1,000,000; U.S. -

(Munich-Augsburg-Rothenburg-Wurzburg-Wiesbaden) Tour Code: DAECO10D9NBAV Day 1: Munich Arrival Munich Airport Welcome to Munich

(Munich-Augsburg-Rothenburg-Wurzburg-Wiesbaden) Tour Code: DAECO10D9NBAV Day 1: Munich Arrival Munich airport Welcome to Munich. Take public transportation to your hotel on your own. Suggestions: Visit one of the many beer pubs with local brewed beer and taste the Bavarian sausage Accommodation in Munich. Day 2: Munich 09:30 hrs Meet your English speaking guide at the hotel lobby for a half day city tour. No admission fee included. Optional full day tour Neuschwanstein castle(joint tour daily excursion bus tour,10.5 hrs). 08:30 hrs: Bus transfer from Munich main station. Admission fee for the castle has to be paid on the bus extra. (In case of Optional Tour Neuschwanstein, half day sightseeing tour of Munich can be done on the 3RD day in the morning). Accommodation in Munich. Copyright:GNTB Day 3: Munich - Augsburg (Historic Highlight City) Transfer by train to Augsburg on your own Suggestions: Visit the Mozart House and the famous Fugger houses. Try the local Swabian cuisine at the restaurant <Ratskeller> or take a refreshing beer in one of the beer gardens in the city. Accommodation in Augsburg Copyright: Regio Augsburg Tourismus GmbH Day 4: Augsburg 09.30 hrs . Meet your English speaking guide at the hotel lobby and start half day city tour of Augsburg. (2 hrs). No admission fee included. Accommodation in Augsburg. Copyright: Stadt Augsburg Day 5: Augsburg - Rothenburg (Romantic Road City) Leave the hotel by train to the romantic city of Rothenburg. At 14:00 hrs, meet your English speaking guide in the lobby of the hotel and start your half day city tour including St. -

KAS International Reports 10/2015

38 KAS INTERNATIONAL REPORTS 10|2015 MICROSTATE AND SUPERPOWER THE VATICAN IN INTERNATIONAL POLITICS Christian E. Rieck / Dorothee Niebuhr At the end of September, Pope Francis met with a triumphal reception in the United States. But while he performed the first canonisation on U.S. soil in Washington and celebrated mass in front of two million faithful in Philadelphia, the attention focused less on the religious aspects of the trip than on the Pope’s vis- its to the sacred halls of political power. On these occasions, the Pope acted less in the role of head of the Church, and therefore Christian E. Rieck a spiritual one, and more in the role of diplomatic actor. In New is Desk officer for York, he spoke at the United Nations Sustainable Development Development Policy th and Human Rights Summit and at the 70 General Assembly. In Washington, he was in the Department the first pope ever to give a speech at the United States Congress, of Political Dialogue which received widespread attention. This was remarkable in that and Analysis at the Konrad-Adenauer- Pope Francis himself is not without his detractors in Congress and Stiftung in Berlin he had, probably intentionally, come to the USA directly from a and member of visit to Cuba, a country that the United States has a difficult rela- its Working Group of Young Foreign tionship with. Policy Experts. Since the election of Pope Francis in 2013, the Holy See has come to play an extremely prominent role in the arena of world poli- tics. The reasons for this enhanced media visibility firstly have to do with the person, the agenda and the biography of this first non-European Pope. -

Biography CHARLOTTE C. BAER, MD October 11, 1908 - August 15, 1973 Dr

Biography CHARLOTTE C. BAER, MD October 11, 1908 - August 15, 1973 Dr. Charlotte Baer was born into a medical family of Wiesbaden, Germany where her father was a practicing physician. He served with distinction in the medical corps of the German Army in World War I and was decorated for his services. It was perhaps natural that his daughter, an only child, would attend medical school. Her father saw to it that at an appropriate time in her life she also attended a cooking school, which, no doubt, accounted for her excellence as a cook, a trait which continued throughout her lifetime. In the European tradition, she attended medical schools throughout Europe and, more than that, lived for varying periods of time in countries other than Germany, giving her considerably more than an elementary knowledge of foreign languages. By the time of her arrival in the United States, she could converse not only in German, but also in English, French, and Italian. As the result of her medical studies, she received MD degrees from the Goethe Medical School Frankfurt am Main and the University of Berne, Switzerland. Throughout her college and medical school years, she found time to continue her enthusiasm for swimming and, in fact, became the intercollegiate breaststroke-swimming champion of Europe. By the time of the Berlin Olympics, she was not permitted to compete for the German team by the Nazi regime because of her Jewish heritage. She did, however, attend the Olympic Games in Berlin and recounted with great pleasure seeing Jesse Owens receive his three gold medals for track and field events withAdolph Hitler being among those present in the stadium. -

Mission Statement

ROBERT B. MOYNIHAN, PH.D ITV MAGAZINE EDITORIAL OFFICES URBI ET ORBI COMMUNICATIONS PHONE: 1-443-454-3895 PHONE: (39)(06) 39387471 PHONE: 1-270-325-5499 [email protected] FAX: (39)(06) 6381316 FAX: 1-270-325-3091 14 WEST MAIN STREET ANGELO MASINA, 9 6375 NEW HOPE ROAD FRONT ROYAL, VA 22630 00153 ROME ITALY P.O. BOX 57 USA NEW HOPE, KY 40052 USA p u d l b r l i o s h w i e n h g t t Résumé for Robert Moynihan, PhD r o t u t d h n a to y Education: the cit • Yale University: Ph.D., Medieval Studies, 1988, M.Phil., 1983, M.A., 1982 Mission Statement • Gregorian University (Rome, Italy): Diploma in Latin Letters, 1986 To employ the written and • Harvard College: B.A., magna cum laude, English, 1977 spoken word in order to defend the Christian faith, and to spread Ph.D. thesis: the message of a Culture of Life • The Influence of Joachim of Fiore on the Early Franciscans: A Study of the Commentary Super to a fallen world desperately in need of the saving truth of the Hieremiam; Advisor: Prof. Jaroslav Pelikan, Reader: Prof. John Boswell Gospel of Christ. Academic Research fields: • History of Christianity • Later Roman Empire • The Age of Chaucer . Contributors include: The Holy See in Rome, Professional expertise: especially the Pontifical Council for Culture Modern History of the Church and the Holy See, with a specialty in Vatican affairs, The Russian Orthodox Church from the Second Vatican Council (1962-65) to the present day. -

Awkward Objects: Relics, the Making of Religious Meaning, and The

Awkward Objects: Relics, the Making of Religious Meaning, and the Limits of Control in the Information Age Jan W Geisbusch University College London Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Anthropology. 15 September 2008 UMI Number: U591518 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U591518 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Declaration of authorship: I, Jan W Geisbusch, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature: London, 15.09.2008 Acknowledgments A thesis involving several years of research will always be indebted to the input and advise of numerous people, not all of whom the author will be able to recall. However, my thanks must go, firstly, to my supervisor, Prof Michael Rowlands, who patiently and smoothly steered the thesis round a fair few cliffs, and, secondly, to my informants in Rome and on the Internet. Research was made possible by a grant from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). -

Religion and the Secular State in Brazil

EVALDO XAVIER GOMES, O. CARM. Religion and the Secular State in Brazil I. SOCIAL CONTEXT According to data furnished by the general census in Brazil in 2000, Brazil had a total population of approximately 170 million inhabitants.1 The next general census, in 2010, revealed that the Brazilian population had reached approximately 200 million.2 In reli- gious terms, Brazil was and continues to be a nation in which Roman Catholicism pre- dominates, low church attendance by the Catholic faithful notwithstanding. Since the be- ginning of the 20th century, however, there has been a continuous decline in the number of Catholics in the composition of the Brazilian population. This tendency was more acute after the 1960s and is shown every ten years by the official census.3 An accentuated reli- gious syncretism also exists, with believers frequenting the worship services of more than one religious confession at the same time. Meanwhile, recent decades have witnessed the strong phenomenon of religious diversification, with a significant reduction in the per- centage of Catholics in the makeup of the Brazilian population,4 owing to the growth of other religious groups, especially the so-called Evangelical or Pentecostal churches.5 A 2007 study by the Getúlio Vargas Foundation, Centre for Social Policies, demon- strated, however, a trend in recent years towards stabilization of these percentages, as observed in the number of Roman Catholics.6 Even so, the changes in the composition of the Brazilian population that have occurred in the last few decades have created a diverse FR. EVALDO XAVIER GOMES, O. CARM, was in January 2014 elected Prior Provincial of the Order of the Car- melites Provincial Chapter of Rio de Janeiro. -

The Impact of Pilgrimage Upon the Faith and Faith-Based Practice of Catholic Educators

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2018 The impact of pilgrimage upon the faith and faith-based practice of Catholic educators Rachel Capets The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Capets, R. (2018). The impact of pilgrimage upon the faith and faith-based practice of Catholic educators (Doctor of Philosophy (College of Education)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/219 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IMPACT OF PILGRIMAGE UPON THE FAITH AND FAITH-BASED PRACTICE OF CATHOLIC EDUCATORS A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy, Education The University of Notre Dame, Australia Sister Mary Rachel Capets, O.P. 23 August 2018 THE IMPACT OF PILGRIMAGE UPON THE CATHOLIC EDUCATOR Declaration of Authorship I, Sister Mary Rachel Capets, O.P., declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Faculty of Education, University of Notre Dame Australia, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. -

Newton Solutions 1

page1 9/22/95 9:55 AM Page 1 Solutions Guide Software, Peripherals and Accessories for Newton PDAs Information Management Desktop Integration Communications Vertical Market Solutions Newton Accessories Newton Software Development page2 9/22/95 9:59 AM Page 1 Suddenly Newton understands everything you write. All you need is Graffiti.® The And here is what some of fastest, most accurate way to the over 20,000 real users are enter text on saying about Graffiti: a Newton.™ Guaranteed. “Graffiti makes a useful device How fast? twice as useful. I now use my Try over 30 Newton constantly.” words a minute. How accurate? “I can take notes at a meeting About 100%. as fast as I print… Every bit as fast And Graffiti takes only twen- as paper and pen.” ty minutes to learn. That’s “I have been using my Newton because it’s really just a simpli- much more than before because fied version of the same Graffiti makes it much easier to alphabet you learned in the first enter data on the fly.” grade. “Just received Graffiti. It’s all they claim and more. I think it’s a must for Newton.”* See for yourself how much you need Graffiti. Call 1-800-881-7256 to order Graffiti for only $79—with a 60-day money-back guarantee. From outside the USA, please call 408-848-5604. *Unsolicited user comments from Graffiti registration cards and Internet news groups. ©1994 Graffiti is a registered trademark and ShortCuts is a trademark of Palm Computing. All other trademarks are property of their respective holders. -

Respect for the Eucharist a Family Prayer Night Publication | Familyprayernight.Org

The Real Presence Project Today’s Topic Respect For The Eucharist A Family Prayer Night Publication | FamilyPrayerNight.org The Eucharist Is Jesus Christ IN THIS EDITION by Stephen J. Marino, Feast of Corpus Christi, 2018 Communitas Dei Patris The Eucharist Is Jesus Christ Do you love the Eucharist? I certainly do! But it wasn’t always that way for Lord The Basics Expanded And me because when I was a boy, and even in the Explained afterward for a time, I just took the Blessed Blessed Sacrament for granted. At times Ways To Reduce Abuses Of The Sacrament. I even questioned whether or not the Eucharist Certainly not by everyone, This is My Body little round host could really be Jesus. and I make no judgment as But, the nuns told me it was and so it Ways To End Abuses Once And to motives or intentions, but must have been true, right? I ended up For All objectively speaking there is leaving the Church and had no religious something seriously amiss in the Church convictions for 20 years. Thank God He Rights, Duties, Responsibilities today. Could it be a crisis of faith? didn’t give up on me. Like the prodigal son, it took a life-changing event for me I’ve seen consecrated hosts that to realize that the Eucharist did in fact have been thrown away, particles of Profanation: The act of mean everything to me…and I do mean consecrated bread (the Body of Christ) depriving something of everything. That was 33 years ago this left in unpurified Communion bowels, its sacred character; a month. -

Hereford Diocesan Newsletter August/September 2018 a Reminder

Hereford Diocesan Newsletter August/September 2018 A Reminder: Date of next Local Gathering in Hereford 22 September 2018 There will be a local diocesan gathering at Hereford on Saturday 22 September. Geraint Bowen, Artistic Director of this year’s festival, will talk about the Three Choirs Festival, and there will be tours of the Song School and the Cathedral gardens. We shall finish with tea and evensong. Please see the separate booking form for further details and do bring a friend – they might become members of FCM! Visit to the Vatican In the last newsletter we mentioned the honour that the cathedral choir had received in being the first Anglican cathedral choir to be invited to sing at the Papal Mass on the Feast of Sts Peter and Paul in St Peter’s Square, as well, as being invited to sing in a concert in the Sistine Chapel before the Pope and the ambassadors to the Holy See with the Sistine Chapel Choir. We are grateful to Ioan O’Reilly, one of the choristers, for writing his account of this momentous visit, which follows below. The service can be seen on YouTube, accessed via the Cathedral website. Rome Trip – 2018 This has been an amazing year for the choir; with performances attended by members of the Royal family and a home Three Choirs Festival! Yet by far the most exciting and exotic part of the year was the choir’s trip to Rome... The choir set out on its travels on Tuesday, 26th June, and in no time at all the fun of the trip had started when the organ scholar forgot his lunch (and upon realising that it was still in his fridge quickly sprinted off). -

The Catholic Church in International Politics Written by Alan Chong

The Catholic Church in International Politics Written by Alan Chong This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. The Catholic Church in International Politics https://www.e-ir.info/2013/11/14/the-catholic-church-in-international-politics/ ALAN CHONG, NOV 14 2013 It is axiomatic in the study of International Relations (IR) to treat the emergence of the Westphalian roots of the present pattern of international society as the simultaneous beginnings of a secular system of sovereign states that acknowledge no authority higher than their own. Power rules relations between states, as realists would have one believe, by imposing fear or attaining goals by overcoming the resistance of the weak. Liberals would seek instead to recast international interaction in terms of an enlightened embrace of win-win logics and belief in the pacific compatibility of differing national interests, if reason were allowed to run its course against the logic of force. The role of the Catholic Church in international politics challenges these assumptions—the dominant pillars of ‘IR theory’—by positing itself as a universal association of governmental and nongovernmental believers in a Christian God. But this does not necessarily mean that the Catholic Church is or has been an entity of spiritual and political perfection since the beginning of the historical time signified by the prefix ‘Anno Domini’. In fact, both the Old and New Testaments that comprise the Holy Bible, the founding text of all Christianity, record a worldwide institution constantly struggling under the multiple overlapping jurisdictions of prophets, their disciples, enlightened lay persons, and even among the rival religious adherents challenging Christianity in a quest for the meaning of the Good.