The Germans in Dobrudscha (Part 6)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROMANIA Irina Vainovski-Mihai1 1 Muslim Populations the First

ROMANIA Irina Vainovski-Mihai1 1 Muslim Populations The first Muslim communities in Romania were formed (mainly in north- ern Dobrudja and along the lower Danube) in the fourteenth century when Ottoman rule was established in the region. Dobrudja remained part of the Ottoman Empire for five centuries. After the Russian- Romanian- Ottoman War (1877), Romania gained its independence and the Treaty of Berlin (1878) acknowledged Dobrudja as part of Romanian territory. As a result of the economic and political conditions in the early twentieth century, Turks and Tatars migrated massively from Dobrudja to Turkey. While the census of 1879 recorded Muslims as representing 56% of the population in the Dobrudjan county of Constantza, the census of 1909 indicates that the percentage had dropped to 10.8%.2 Since its establish- ment as an independent state, the Constitutions of Romania and special laws have guaranteed the rights of certain religious groups, in addition to Orthodox Christians who represent the majority of the population. The law on religious denominations adopted in 1923 lists the Muslim faith among the recognised ‘historical faiths’.3 The establishment of the Com- munist regime (1948) introduced many formal changes with regard to the recognition of religious denominations, but put them under strict state control. Between 1948 and 1989, the Communist state acted systematically to impose atheism and limit the impact of religious creeds on society. 1 Irina Vainovski-Mihai is Associate Professor in Arabic Literature at Dimitrie Cantemir Christian University, Bucharest. She holds a degree in Arabic language and literature and a Ph.D. in Philology. She has published studies in Arab literature, comparative literature and intercultural stereotyping. -

Agenţia Judeţeană Pentru Plăţi Şi Inspecţie Socială CONSTANTA RAPORT PRIVIND ALOCAŢIA DE STAT PENTRU COPII Luna De

Agenţia Judeţeană pentru Plăţi şi Inspecţie Socială CONSTANTA RAPORT PRIVIND ALOCAŢIA DE STAT PENTRU COPII Luna de raportare: 11/2020 Suma totală platită pentru drepturile Localitate Beneficiari plătiţi curente (lei) 23 AUGUST 884 182860 ADAMCLISI 483 97635 AGIGEA 1386 285114 ALBESTI 749 154573 ALIMAN 594 119642 AMZACEA 551 112055 BANEASA 1367 276815 BARAGANU 453 91717 CASTELU 1280 264400 CERCHEZU 281 56401 CERNAVODA 3146 647330 CHIRNOGENI 618 123898 CIOBANU 670 134070 CIOCARLIA 578 116498 COBADIN 1970 397754 COGEALAC 1048 213016 COMANA 452 91716 CONSTANTA 47307 9654867 CORBU 1140 229300 COSTINESTI 544 113520 CRUCEA 540 107812 CUMPANA 2867 587619 CUZA VODA 1325 269413 DELENI 490 97090 DOBROMIR 1242 249458 DUMBRAVENI 101 21077 EFORIE 1493 299573 FANTANELE 292 58804 GARLICIU 298 61386 GHINDARESTI 354 72666 GRADINA 210 42530 HARSOVA 2217 450257 1 Suma totală platită pentru drepturile Localitate Beneficiari plătiţi curente (lei) HORIA 174 36054 INDEPENDENTA 607 122415 ION CORVIN 461 93381 ISTRIA 524 106140 LIMANU 1053 210445 LIPNITA 523 103563 LUMINA 2011 408099 MANGALIA 5957 1202877 MEDGIDIA 7223 1472047 MERENI 531 106331 MIHAI VITEAZU 966 192878 MIHAIL KOGALNICEANU 1626 326938 MIRCEA VODA 1280 261456 MURFATLAR 1956 399028 NAVODARI 6712 1373464 NEGRU VODA 1108 224300 NICOLAE BALCESCU 1112 224304 OLTINA 467 95227 OSTROV 870 174198 OVIDIU 2819 574507 PANTELIMON 453 92269 PECINEAGA 675 136467 PESTERA 688 138872 POARTA ALBA 1384 280144 RASOVA 782 159206 SACELE 471 93943 SALIGNY 382 78582 SARAIU 229 45493 SEIMENI 401 79705 SILISTEA 316 63428 TARGUSOR -

RO Sperrung Agigea-Brücke Anlage 2

REGIERUNG VON RUMÄNIEN MINISTERIUM FÜR VERKEHR UND INFRASTRUKTUR Direktorat für Europäische Angelegenheiten und allgemeine internationale Beziehun- gen Bukarest, 26.7.2012 Gemäß Verordnung (EG) Nr. 2679/98 des Rates vom 7. Dezember 1998 über das Funktio- nieren des Binnenmarktes im Zusammenhang mit dem freien Warenverkehr zwischen den Mitgliedstaaten informiert das Ministerium für Verkehr und Infrastruktur die Nutzer der rumä- nischen Nationalstraßen wie folgt: Die nationale Gesellschaft für Autobahnen und Nationalstraßen in Rumänien informiert die Verkehrsteilnehmer darüber, dass mit Beginn ab 26.07.2012, 18 Uhr bis 26.10.2012 der Verkehr auf der DN 39 Constanta Mangalia bei km 8+988 „AGIGEA-BRÜCKE“ auf Mo- torfahrzeuge mit einem maximalen zulässigen Gesamtgewicht von 5 Tonnen be- schränkt wird, mit der Ausnahme von solchen Fahrzeugen, die Aktivitäten im Perso- nentransport durchführen. Wir möchten auch erwähnen, dass die maximale Reisegeschwindigkeit für den Straßen- verkehr auf 30 km/h beschränkt wird . Diese Verkehrsbeschränkung wird nötig wegen der Durchführung von Brückenreparatur- maßnahmen bzw. der Erneuerung von Drahtverspannungen, die zur Haltbarkeitsstruktur der Brücke gehören. Während der Dauer der Beschränkungen wird der Verkehr für Fahrzeuge mit einem zulässi- gen Gesamtgewicht über 5 Tonnen über folgende Umleitungen geführt: Auf der Strecke: Bukarest – Constan ţa Südhafen – Agigea - Negru Vod ă - Mangalia bzw. umgekehrt: A2 (Bukarest – Cernavod ă – Anschlussstelle Medgidia) – DJ 381 (Anschluss- stelle Medgidia – Ciocârlia -

Județul CONSTANȚA

Constanta ASISTENTA SOCIALA Directia Generala de Asistenta Sociala si Protectia Copilului CONSTANTA http://www.dgaspc-ct.ro Adresa: Str.Decebal; nr. 22 Constanta – 900 665 Telefon: 0241 480 851 Fax: 0241 694 137 E-mail: [email protected] Servicii pentru victime DIRECTIA GENERALA DE ASISTENTA SOCIALA SI PROTECTIA COPILULUI CONSTANTA Telefon: 0241.480851 Servicii pentru victimele violentei în familie: Asistenta sociala Consiliere psihologica Consiliere juridica Informarea si orientarea victimelor violentei în familie SECTII de POLITIE POLITIA MURFATLAR STR. ELIADE MIRCEA nr. 1 MURFATLAR, CONSTANTA 0241-234 020 POLITIA MIHAIL KOGALNICEANU COM. MIHAIL KOGALNICEANU, CONSTANTA 0241-258 024 POLITIA OSTROV STR. 1 MAI nr. 73 COM. OSTROV, CONSTANTA 0241-857 007 POLITIA AGIGEA COM. AGIGEA, CONSTANTA 0241-738 525 POLITIA OLTINA STR. POLITIEI nr. 713B COM. OLTINA, CONSTANTA 0241-851 713 POLITIA SARAIU STR. TULCEI nr. 26 COM. SARAIU, CONSTANTA 0241-873 359 POLITIA NEPTUN STR. PLOPILOR nr. 1 NEPTUN, CONSTANTA 0241-731 549 POLITIA CONSTANTA-SECTIA 3 STR. STEFAN CEL MARE nr. 103 CONSTANTA, CONSTANTA 0241-664 262 POLITIA NICOLAE BALCESCU COM. NICOLAE BALCESCU, CONSTANTA 0241-257 008 POLITIA CONSTANTA-SECTIA 1 STR. CHILIEI CONSTANTA, CONSTANTA 0241-559 868 POLITIA TOPRAISAR SOS. NATIONALA nr. 59 COM. TOPRAISAR, CONSTANTA 0241-785 007 POLITIA CIOCÂRLIA STR. 1 DECEMBRIE COM. CIOCÂRLIA, CONSTANTA 0241-875 557 POLITIA DELENI STR. MILITARI nr. 73 COM. DELENI, CONSTANTA 0241-854 700 POLITIA CIOBANU STR. EROILOR nr. 76 COM. CIOBANU, CONSTANTA 0241-874 839 POLITIA COMANA COM. COMANA, CONSTANTA 0241-859 445 POLITIA CONSTANTA-SECTIA 2 STR. TULCEA nr. 9 CONSTANTA, CONSTANTA 0241-543 232 POLITIA PANTELIMON ULMETTUM 99 COM. -

LISTA OPERATORILOR DE TRANSPORT RUTIER CARE EFECTUEAZA TRANSPORT DE MARFURI CU VEHICULE SPECIALIZATE Nr

LISTA OPERATORILOR DE TRANSPORT RUTIER CARE EFECTUEAZA TRANSPORT DE MARFURI CU VEHICULE SPECIALIZATE Nr. Crt. Judet CodFiscal Denumire Adresa Localitate Telefon Fax STR.M. 1 AB RO18877875 ADI & IULIA SRL SEBES 0724487593 KOGALNICEANU;BL.142;SC.A;ETJ.1;AP.6 2 AB RO1761050 AGROTRANSPORT ALBA SA STR.LIVEZII NR.35 A ALBA IULIA 0372742226 0258817826 3 AB RO10116461 ALBA CONS SA VASILE GOLDIS NR.8 B ALBA IULIA 834115;834116 OARDA,MUN.ALBA IULIA,STR.BIRUINTEI 4 AB RO8873604 ALBACO EXIM SRL ALBA IULIA 0258811794 NR.46 5 AB RO14099142 ALOREF SRL SOSEAUA DE CENTURA NR.2 ALBA IULIA 835554 6 AB RO5900631 ALPIN 57 LUX SRL STR.RASTOACA;NR.7 SEBES 0258730203 0744571957 7 AB RO21459090 ALREDIA SRL STR.VULCAN NR.14 AIUD 0732850000 8 AB RO6387241 ANCA FOREST SRL DOLESTI;NR.352 AVRAM IANCU 9 AB RO1755482 APA-CTTA SA VASILE GOLDIS Nr. 3 ALBA IULIA 834501 834501 10 AB RO23073907 ARIA CONSTRUCT SRL STR.DINU LIPATI NR.8 ALBA IULIA 0745345209 11 AB RO27590264 BIO RECYCLING SRL ALEEA LAC;NR.2-3;AP.6 SEBES 0744124181 0258731733 12 AB RO13609073 CETATEA DE BALTA S.R.L. STR.GARII,NR32 JIDVEI 881880;881160 881038 13 AB RO21031298 CLASS BETON SRL Str.IULIU MANIU,Nr1E BLAJ 0722711185 14 AB RO16651226 COMA CONSTRUCT SRL STR.CALUGARENI NR.3 SEBES 0258733583 15 AB RO13813781 COMINCO TRANSILVANIA SA STR.DETUNATA;NR.65-67 ABRUD 780774 780447 16 AB RO1756720 COMPACT CONSTRUCT STR.M. KOGALNICEANU;NR.49 ALBA IULIA 814513 COTISEL CONSTANTIN PERSOANA 17 AB 20857390 LAZURI NR.162 SOHODOL 0748149494 FIZICA AUTORIZATA 18 AB RO16576302 DANYON TRANS SRL TELNA STR.PRINCIPALA NR.298 COMUNA IGHIU 0724/209066 0728242845;0744432 19 AB RO25294858 DN AGRAR SERVICE S.R.L. -

List of German Settlements in the Dobrudscha 1928 & 1934

List of German Settlements in the Dobrudscha 1928 & 1934 Source: Deutscher Volkskalender für Bessarabien – 1928 Tarutino Press and Printed by Deutschen Zeitung Bessarabiens Pages 52 Internet Location: urn:nbn:de:bvb:355-ubr13937-1 Transcribed by: Allen E. Konrad December, 2016 ================================================================ [Transcription Begins] [1928] ===================================================================== Place Community Postal Station District Souls ===================================================================== Admagea Ciucorova Babadag Tulcea 390 Agemler Osmarcea Medgidia Constantsa 40 Alacap Alacap Murfatlar Constantsa 150 Anadolchioi Constantsa Constantsa Constantsa 250 Caratai Chiostel Medgidia Constantsa 150 Cataloi Cataloi Cataloi Tulcea 330 Ciubancuius — — Durostor (?) Ciucorova Ciucorova Babadag Tulcea 400 Cobadin Cobadin Cobadin Constantsa 460 Cogealac Cogealac Cogealac Constantsa 730 Cogealia Cogealia Constantsa Constantsa 320 Constantsa Constantsa Constantsa Constantsa City Fachreia Fachreia Cernavoda Constantsa 350 Horoslar Canora Murfatlar Constantsa 140 Mamuslia Caraomer Caraomer Constantsa 220 Neue Weingärten Hasiduluc Constantsa Constantsa 130 (Viili noi) Ortachioi Reg. Maria Reg. Maria Tulcea 40 Sarighiol Sarighiol Mangalia Constantsa 370 Sofular Dobadin Medgidia Constantsa 90 Tariverde Cogealac Cogealac Constantsa 780 [Transcription Ends for 1928] Source: Deutscher Volkskalender für Bessarabien – 1934 Tarutino Press and Printed by Deutschen Zeitung Bessarabiens Pages 48 Internet -

Pdf (Accessed in December 2017)

Balkanologie Revue d'études pluridisciplinaires Vol. 15 n° 1 | 2020 Mémoires performatives : faire des passés et des présents Remembering and being. The memories of communist life in a Turkish Muslim Roma community in Dobruja (Romania) Se souvenir et exister. Les mémoires de la vie sous le communisme dans une communauté rom musulmane turcophone de Dobrudja (Roumanie) Adriana Cupcea Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/balkanologie/2497 DOI: 10.4000/balkanologie.2497 ISSN: 1965-0582 Publisher Association française d'études sur les Balkans (Afebalk) Electronic reference Adriana Cupcea, “Remembering and being. The memories of communist life in a Turkish Muslim Roma community in Dobruja (Romania)”, Balkanologie [Online], Vol. 15 n° 1 | 2020, Online since 01 June 2020, connection on 05 August 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/balkanologie/2497 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/balkanologie.2497 This text was automatically generated on 5 August 2021. © Tous droits réservés Remembering and being. The memories of communist life in a Turkish Muslim Rom... 1 Remembering and being. The memories of communist life in a Turkish Muslim Roma community in Dobruja (Romania) Se souvenir et exister. Les mémoires de la vie sous le communisme dans une communauté rom musulmane turcophone de Dobrudja (Roumanie) Adriana Cupcea 1 My research is part of a direction regarding the current situation of the Turkish Muslim Roma in the national states of the Balkans, created after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, and it puts forward the description of a Muslim Roma Turkish-speaking community in a post-socialist city, Medgidia (Mecidiye), in the south-eastern part of Dobruja. -

NORTHERN DOBROGEA Abundant Andthefishare Nervous

© Lonely Planet 290 Northern Dobrogea Northern Dobrogea is undeniably a kingdom unto itself within Romania. Despite the lack of prevailing Romanian icons (breathtaking mountains, ancient churches, the undead), the Danube River (Râul Dunărea) and the Black Sea coast (Marea Neagră) contain offerings rang- ing from all nature to au natural. The 194km coastline (litoral) attracts waves of wildlife and party animals alike. Equally, those seeking waterfront seclusion, archaeological stimulation and overwhelming numbers of exotic birds won’t be disappointed. Though widely considered to be the least ‘Romanian’ part of the country, ironically, this is where the strongest evidence of Romania’s conspicuously proud connection to ancient NORTHERN DOBROGEA Rome is found in the form of statues, busts, sarcophagi and other archaeological finds. The cultural distance from the rest of Romania can be partially explained by the unusually broad ethnic diversity in the area. Sizeable Turkish, Tatar, Bulgarian, Ukrainian and Lippovani/Old Believer settlements add to the mix, giving the area a refreshing burst of multiculturalism. History and culture notwithstanding, marine life still rules supreme here, despite tenacious attempts by humans to usurp the crown. On one hand we have the 65km stretch south of Mamaia where humans converge in beach resort towns to soothe their bodies with sunshine and curative mud. These restorative pursuits are then promptly annulled hours later by glut- tonous feasts and some of the wildest clubbing in the country. Alternately, the calming and notably less opulent Danube Delta draws bird-lovers and seekers of solitude. A fantastic, tangled network of ever-eroding canals, riverbeds and wetlands in Europe’s second-largest delta boasts remote fishing villages and stretches of deserted coast, where the pelicans are abundant and the fish are nervous. -

226747542.Pdf

Marin CONSTANTIN APARTENENȚȚAA ETNO‐‐CULTURALĂĂ DIN ROMÂNIA ÎN CONTEXTUL GLOBALIZĂĂRII CRITERII ANTROPOLOGICE ALE ETNOGENEZEI ŞŞI I ETNOMORFOZEI APARTENENȚȚAA ETNO‐‐CULTURALĂĂ DIN ROMÂNIA ÎNÎN CONTEXTUL GLOBALIZĂĂRII CRITERII ANTROPOLOGICE ALE ETNOGENEZEI Ş ŞI I ETNOMORFOZEI Autor: Marin CONSTANTIN Conducăătortor ş ştiințțific: Dr. Cristiana GLAVCE Lucrare realizatăă în în cadrul proiectului „„Valorificarea identitățăților culturale înîn procesele globale”,”, cofinanțțatat din Fondul Social European prin Programul Operațțional Sectorial Dezvoltarea Resurselor Umane 2007 –– 2013, contractul dede finanțțare nr.nr. POSDRU/89/1.5/S/59758. Titlurile şşii drepturile dede proprietate intelectuală şşii industrialăă asupra rezul‐‐ tatelor obobțținute în în cadrul stagiului dede cercetare postdoctoralăă aparțținin Academiei Române. Punctele dede vedere exprimate înîn lucrare aparțținin autorului ş şii nunu angajeazăă Comisia Europeană şă şii Academia Română ă , , beneficiara proiectului. Exemplar gratuit. Comercializarea în în ț țarară şă şii strstrăăininăătate este interzisăă.. Reproducerea, fiefie ş şii parțțialială şă şii pepe orice suport, este posibilăă numai cucu acordul prealabil alal Academiei Române. ISBN 978‐‐973‐‐167‐‐134‐‐55 Depozit legal: Trim. IIII 2013 Marin CONSTANTIN Apartenențța etno‐‐culturală din România în contextul globalizării Criterii antropologice ale etnogenezei şşii etnomorfozei Editura Muzeului Națțional alal Literaturii Române Colecțțiaia AUL AULAA MA MAGNAGNA CUPRINS INTRODUCERE.......................................INTRODUCERE.................................................................................................................................................................. -

DIRECŢIA JUDEŢEANĂ CONSTANŢA a ARHIVELOR NAŢIONALE Lista Fondurilor Şi Colecţiilor Care Se Dau În Cercetare Deţinute De

DIRECŢIA JUDEŢEANĂ CONSTANŢA A ARHIVELOR NAŢIONALE Lista fondurilor şi colecţiilor care se dau în cercetare deţinute de Direcţia Judeţeană Constanţa a Arhivelor Naţionale Nr. Denumirea fondului sau colecţiei Anii extremi Nr. U.A. crt. Nr. inventar 1. 13 Administraţia Vamală Constanţa 1924 - 1948 253 2. 352 Ansamblul Artistic “Brâuleţul” Constanţa 1963 – 1970 16 3. 539 Asociaţia Română pentru Legături cu Uniunea Sovietică 1956 – 1963 8 4. 220 Atelierele “Secera şi Ciocanul” Constanţa 1945 – 1951 56 5. 191 Banca Agricolă – Sucursala Constanţa 1955 - 1960 153 6. 196 Banca Comercială Română – Sucursala Constanţa 1946 – 1947 2 7. 181 Banca “Creditului Dobrogei” - Constanţa 1921 - 1944 11 8. 52 Banca Creditului Naţional Agricol 1938 – 1948 63 9. 219 Banca Naţională a României – Sucursala jud. Constanţa 1929 – 1966 161 10. 192 Banca Naţională a RSR – Direcţia Orăşenească Constanţa 1952 - 1966 109 11. 194 Banca Naţională Filiala Mangalia 1949 – 1955 19 12. 193 Banca Naţională Filiala Negru Vodă 1956 - 1966 11 13. 51 Banca Românească Constanţa 1915 – 1951 471 14. 195 Banca Sovieto – Română, Constanţa 1953 – 1954 22 15. 87 Camera Agricolă a jud. Constanţa 1939 – 1949 167 16. 88; 228 Camera de Comerţ – jud. Constanţa 1920 – 1950 8099 17. 11; 36; Camera de Muncă Constanta 1933 - 1948 12481 37 18. 499 CAP Anadalchioi 1958 – 1986 95 19. 494 CAP Valea Seacă 1952 – 1989 64 20. 493 CAP Valul lui Traian 1952 – 1990 69 21. 498 CAP Viile Noi 1952 – 1980 164 22. 111 Căpitănia Portului Constanţa 1892 – 1950 307 23. 171 Căpitănia Portului Mangalia 1919 – 1952 53 24. 497 Căpitănia Portului Ostrov 1936 – 1982 199 25. -

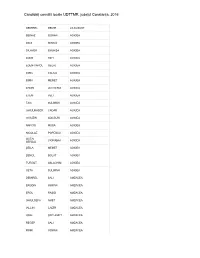

Candidați Consiliii Locale UDTTMR, Județul Constanța, 2016

Candidați consiliii locale UDTTMR, județul Constanța, 2016 DEMIREL DEMIR 23 AUGUST BEINAZ OSMAN AGIGEA DICA MIRICǍ AGIGEA DILAVER EMURŞA AGIGEA EDEN REFI AGIGEA EDEN-VAROL GELAL AGIGEA EMEL CALILA AGIGEA EMIN MEMET AGIGEA ERDIN ZECHERIA AGIGEA ETEM VELI AGIGEA FAIC SULIMAN AGIGEA GHIULMABER CADȂR AGIGEA GHIUZIN ADILBURI AGIGEA NARCIS MUSA AGIGEA NICOLAE POPESCU AGIGEA OCTAI- CIORABAI AGIGEA SERDAL ŞEILA MEMET AGIGEA ŞENOL BOLAT AGIGEA TURGUT ABLACHIM AGIGEA VETA SULIMAN AGIGEA DEMIREL SALI AMZACEA ERODIN OSMAN AMZACEA EROL RAŞID AMZACEA GHIULSEFA AMET AMZACEA IALCIN CADÎR AMZACEA ORAL SEIT-AMET AMZACEA REGEP SALI AMZACEA ROMI OSMAN AMZACEA Candidați consiliii locale UDTTMR, județul Constanța, 2016 SABRI ABIBULA AMZACEA ŞAGATAI OSMAN AMZACEA UMIRAN MUSTAFA AMZACEA BEDRIE ABDULA CASTELU CADRIE OSMAN CASTELU CAMEL CURTGEAFAR CASTELU ENAN ZEINEDIN CASTELU EROL SULIMAN CASTELU GHIULSEN MAMUT CASTELU LEILA SOIUN CASTELU METIN SEIHISLEAM CASTELU REBI SALIM CASTELU SABAN SABAN CASTELU SACHIR SALI CASTELU SADIC MUSTAFA CASTELU SAIT OSMAN CASTELU SAMIR SALI CASTELU SINAN BECHIR CASTELU SUEIDA SULEIMAN CASTELU TANER CURTGEAFAR CASTELU TEFUC DAUT CASTELU ULCHER ALI-AGI CASTELU AFIZE MUSTAFA COBADIN BEINUR ASAN COBADIN BEINUR CIORACAI COBADIN ELIS ISA COBADIN ELIŞAN IUSMEN COBADIN ELVIS MUSTAFA COBADIN Candidați consiliii locale UDTTMR, județul Constanța, 2016 ERDUAN ISMAIL COBADIN NARDIN MUTALÎP COBADIN NURTEN COLDAŞ COBADIN OZGYN ABDULA COBADIN RAIM COLDAŞ COBADIN SEDIR ABDULACHIM COBADIN SEMIRAL DEMIR COBADIN SERVIS MUSTAFA COBADIN SEVER SALIM COBADIN -

NTS Cobadin Ver 1

Cobadin Wind Farm, Romania Non-Technical Summary Date: February 2013 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 1 2. SETTING AND LOCATION OF WIND FARM ................................................................................. 2 3. DESCRIPTION OF THE WIND FARM ............................................................................................. 3 3.1 DESCRIPTION OF EQUIPMENT AND INFRASTRUCTURE ................................................... 3 4. ENVIRONMENTAL, HEALTH, SAFETY AND SOCIAL REVIEW OF PROJECT ........................ 4 4.1 SCOPE OF WORK ....................................................................................................................... 4 4.2 SITE OBSERVATIONS ................................................................................................................. 4 4.3 EIA REVIEW AND GAP ANALYSIS ........................................................................................... 5 5. PLANNING AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS ............................................................................ 6 5.1 ECOLOGY .................................................................................................................................... 6 5.2 LANDSCAPE AND VISUAL IMPACT .......................................................................................... 7 5.3 NOISE & VIBRATION ..................................................................................................................