What Not to Wear: Policing the Body Through Fashion Criticism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indian Textile Industry Happy with GST Rates on Cotton Value Chain, but Disappointed at High Rates on Man-Made Fibres and Yarns P26

Apparel Online India 2 2 Apparel Online India | JUNE 16-30, 2017 | www.apparelresources.com www.apparelresources.com | JUNE 16-30, 2017 | Apparel Online India 3 4 Apparel Online India | JUNE 16-30, 2017 | www.apparelresources.com 4 Apparel Online India www.apparelresources.com | JUNE 16-30, 2017 | Apparel Online India 5 Apparel Online India 5 CONTENT Vol. XX ISSUE 6 JUNE 16-30, 2017 World Wrap 38 Fashion Activism: Voice your opinion; designers join the political debate p12 Fashion Business Tied together with a smile: Focus on Fastenings and Closures for Fall/Winter 2017-18 Sustainability H2F KPR Mills: Phenomenal Diversification: educational initiatives make The survival key for many unfulfilled dreams medium-level exporters come true p16 in Delhi-NCR p30 22 Market Update Challenges apart, Japan has huge scope for Indian exporters FFT Trends Key Silhouettes and Details: Fall/Winter 2017-18 p33 Resource Centre Navis Global keeping pace with global demand; Asian markets account for 75% of business p58 Tex-File Indian textile industry happy with GST rates on cotton value chain, but disappointed at high rates on man-made fibres and yarns p26 6 Apparel Online India | JUNE 16-30, 2017 | www.apparelresources.com E-FIT PROVIDING SUPPLY CHAIN SOLUTIONS DURING PRE-PRODUCTION ACTIVITIES Intertek oers state-of-the-art studio endowed with modern automated technology utilizing the 3-dimensional software for the E-FIT check and fabric consumption calculation. E-FIT uses advance technology to moderate the requirements with minimizing operation cost. Contact -

'GCB' Star Miriam Shor Opens Up

PAGE b8 THE STATE JOURNAL mR A cH 1, 2012 Thursday ALMANAC 50 YEARS AGO ‘GCB’ star Miriam Shor opens up A surprise family dinner party was held at the Frank- fort Country Club in honor of William D. Gray, who was cel- Versatile actress takes on role of Southern belle in ABC comedy ebrating his birthday. Guests included Mr. and Mrs. Speed Gray, Mr. and Mrs. Arthur L. By Karen ZarKer year-old this book called Miriam Shor 13. You feel best in Armani Gray, Lucy Gray Poston, Mr. Po PMATTers.coM “And Tango Makes Three,” plays Cricket or Levis or ...? and Mrs. William A. Gray, You’ve seen her as Janet about the gay penguin couple Caruth-Reilly, I like to wear what my Master William Gray and the Thompson in “Swingtown,” at the Central Park Zoo. They a powerful husband calls “inside honored guest. as Anna in “Mildred Pierce” cared for an orphan egg ‘til it real estate pants,” as in “don’t wear and as Yitzhak in “Hedwig hatched and then raised the agent in those pants outside.” Com- 25 YEARS AGO baby penguin as their own. I A heavy rain caused flood- and The Angry Inch” (on Dallas whose fort first. I’m not ashamed. cannot get through this book ing in a picnic area off U.S. Broadway and in the feature husband, without copious amounts of 14. Your dinner guest at 127 and contributed to a film) – to name just a few of Blake, is gay, tears and snot running down the Ritz would be? Thornhill Bypass accident this prolific actor’s roles. -

Lyric Ramsey Resume 2017

[email protected] // 310-722-0174 Member of the Motion Picture Editors Guild - IATSE Local 700 SUPERVISING EDITOR On Tour With / BET / Entertainment One / Documentary Sisterhood Of Hip Hop Season 3 / Oxygen / 51 Minds / Doc-series Sisterhood Of Hip Hop Season 2 / Oxygen / 51 Minds / Doc-series LEAD EDITOR Grand Hustle/ BET / Endemol/ Competition-Reality Born This Way/ Scripted - Comedy She Got Game / VH1 / 51 Minds / Competition-Reality Suave Says / VH1 / 51 Minds / Doc-series Weave Trip / VH1 / 51 Minds / Doc-series EDITOR Below Deck 5/ Bravo / 51 Minds / Doc-series The Pop Game / Lifetime / Intuitive Entertainment / Competition-Reality Project Runway Juniors 2 / Lifetime / The Weinstein Company / Competition-Reality Below Deck Med / Bravo / 51 Minds / Doc-series Below Deck 4/ Bravo / 51 Minds / Doc-series Project Runway Juniors / Lifetime / The Weinstein Company / Competition-Reality Workout NY / Bravo / All3Media / Doc-series The Singles Project / Bravo / All3Media / Documentary *2015 Emmy Winner for Outstanding Creative Interactive Show Same Name / CBS / 51 Minds / Doc-series Marrying the Game Season 3 / VH1 / 51 Minds / Doc-series LA Hair Season 3 / WeTv / 3Ball Productions / Eyeworks / Doc-series Mind of a Man / GSN / 51 Minds / Game Show Scrubbing In / MTV / 51 Minds / Doc-series Heroes of Cosplay / SyFy / 51 Minds / Competition-Reality LA Hair Season 2 / WeTv / 3Ball Productions / Eyeworks / Doc-series Full Throttle Saloon / TruTV / A. Smith & Co. / Doc-series Finding Bigfoot / APL / Ping Pong Productions / Doc-series Trading -

I Was Tempted by a Pretty Coloured Muslin

“I was tempted by a pretty y y coloured muslin”: Jane Austen and the Art of Being Fashionable MARY HAFNER-LANEY Mary Hafner-Laney is an historic costumer. Using her thirty-plus years of trial-and-error experience, she has given presentations and workshops on how women of the past dressed to historical societies, literary groups, and costuming and re-enactment organizations. She is retired from the State of Washington . E E plucked that first leaf o ff the fig tree in the Garden of Eden and decided green was her color, women of all times and all places have been interested in fashion and in being fashionable. Jane Austen herself wrote , “I beleive Finery must have it” (23 September 1813) , and in Northanger Abbey we read that Mrs. Allen cannot begin to enjoy the delights of Bath until she “was provided with a dress of the newest fashion” (20). Whether a woman was like Jane and “so tired & ashamed of half my present stock that I even blush at the sight of the wardrobe which contains them ” (25 December 1798) or like the two Miss Beauforts in Sanditon , who required “six new Dresses each for a three days visit” (Minor Works 421), dress was a problem to be solved. There were no big-name designers with models to show o ff their creations. There was no Project Runway . There were no department stores or clothing empori - ums where one could browse for and purchase garments of the latest fashion. How did a woman achieve a stylish appearance? Just as we have Vogue , Elle and In Style magazines to keep us up to date on the most current styles, women of the Regency era had The Ladies Magazine , La Belle Assemblée , Le Beau Monde , The Gallery of Fashion , and a host of other publications (Decker) . -

The Fashion Industry As a Slippery Discursive Site: Tracing the Lines of Flight Between Problem and Intervention

THE FASHION INDUSTRY AS A SLIPPERY DISCURSIVE SITE: TRACING THE LINES OF FLIGHT BETWEEN PROBLEM AND INTERVENTION Nadia K. Dawisha A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Communication in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Patricia Parker Sarah Dempsey Steve May Michael Palm Neringa Klumbyte © 2016 Nadia K. Dawisha ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Nadia K. Dawisha: The Fashion Industry as a Slippery Discursive Site: Tracing the Lines of Flight Between Problem and Intervention (Under the direction of Dr. Patricia Parker) At the intersection of the glamorous façade of designer runway shows, such as those in Paris, Milan and New York, and the cheap prices at the local Walmart and Target, is the complicated, somewhat insidious “business” of the fashion industry. It is complicated because it both exploits and empowers, sometimes through the very same practices; it is insidious because its most exploitative practices are often hidden, reproduced, and sustained through a consumer culture in which we are all in some ways complicit. Since fashion’s inception, people and institutions have employed a myriad of discursive strategies to ignore and even justify their complicity in exploitative labor, environmental degradation, and neo-colonial practices. This dissertation identifies and analyzes five predicaments of fashion while locating the multiple interventions that engage various discursive spaces in the fashion industry. Ultimately, the analysis of discursive strategies by creatives, workers, organizers, and bloggers reveals the existence of agile interventions that are as nuanced as the problem, and that can engage with disciplinary power in all these complicated places. -

Giambattista Valli for Impulse Only at Macy’S

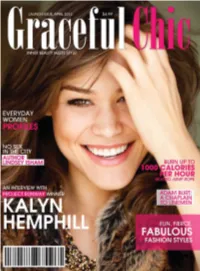

Giambattista Valli for Impulse only at macy’s Launch Issue April 2012 Cover Stories Kalyn Hemphill An interview with Project Runway model winner 75 The Fall Collection New York Fashion Week Sneak Preview 23 AD Author Lindsey Isham On Relationships and Her Book “No Sex In The City” 65 Adam Burt Chaplain to Linemen: From Professional Hockey Player to a Family Man 85 Beaded Jump Rope Burn Up to 1000 Colaries Per Hour 102 Dress By Luminaa LLC By Luminaa LLC 5 Graceful Chic / Launch Issue 2012 The Lasting Sheer® Collection Ultra Sheer The NewsBoys In Central Park 81 Fashion Reflection Everyday Women 103 Fun Fience Fabulous 13 Faith and fashion, 29 Nicola Curry Fashion Styles Chrisianity and Catwalk: Do 43 Raychael Arianna these two Meet? 20 The Legend Lives on: 53 Lindy Leiser Alexander MacQueen 59 Sara Presley Resort Collection Beauty 73 Caprice Taylor 31 Coye Nokes’s Queen of the 55 Makeup 101: 93 Andromedo Turre Nile Shoe Collection 5 Tips to keep your face in 99 Melissa Peraldo place all day long 33 Ode to the Little Black Dress 56 Lip Gloss: Winter TLC NUTRITION Soft, sensual and luxuriously beautiful. 37 95 Filling up with Fiber: New York, New York: Exceptional sheerness Easy Casual Styles for 63 Inner Beauty: Four Simple Swaps everyday in the big city Mirror Mirror on the Wall 97 Spice Spotlight: Ginger with run resistant confidence. “I feel ugly today” 43 Fashion Bargain It’s Ultra Sheer perfected! Shopping Tips 119 Home is where the story 51 Relationships begins: The festive, easy Fashion Jewelry for Freedom brunch with friends by WAR -

GREEN AMERICAN GREENAMERICA.ORG the High Cost of Clothes

WINTER 2019 ISSUE 116 LIVE BETTER. SAVE MORE. INVEST WISELY. MAKE A DIFFERENCE. GREEN GREENAMERICA.ORG AMERICAN Unraveling the Fashion Industry It’s easy to ignore the huge influence garments have on workers and the planet. Luckily, activists and businesses are working to make the fashion industry better. If you wear clothes, you can too. ARE THESE TRENDS WORKER- FROM FAST WHAT HAPPENS GREEN OR APPROVED SOCIAL TO FAIR TO UNWANTED GREENWASHED? p. 10 RESPONSIBILITY p. 20 FASHION p. 24 CLOTHES? p. 27 VisionCapital ColorLogo Ad 3/29/06 9:29 PM Page 1 FREE IS YOUR YOUR MONEY VALUES BIG GAP IN BETWEEN? GOOD YOU CAN BRIDGE THE GAP with ▲▲▲▲▲▲ Individualized Portfolios Customized Social Criteria High Positive Social Impact Competitive Financial Returns Personalized Service Fossil Free Portfolios. Low Fixed Fees David Kim, President, a founder of Learn more at socialk.com Working Assets, in SRI since 1983. 1.800.366.8700 www.visioncapitalinvestment.com VISION CAPITAL INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT Socially Responsible Investing Were you born in 1949 or earlier? If you answered yes to that question, and you have a traditional IRA, then there’s a smarter way to give to Green America! You can make a contribution, also known as a Qualified Charitable Distribution (QCD), from your IRA that is 100% tax free, whether or not you itemize deductions on your tax return. Learn more about QCD donations and make a gift that will grow the green economy for the people and the planet. Visit FreeWill.com/qcd/ GreenAmerica to get started. FreeWill is not a law firm and its services are not a substitute for an attorney’s advice. -

Katrina Cooney

Katrina Cooney Casting Experience Top Chef 17 (Bravo) - Magical Elves, 2019 Casting Manager Project Runway 18 (Bravo) - Magical Elves, 2019 Casting Manager Are You The One? Fluid (MTV) - Lighthearted Entertainment, 2019 Casting Manager Project Runway 17 (Bravo) - Magical Elves, 2018 Casting Manager Project Runway 17 (Unaired/No Network) - Bunim/Murray, 2018 Casting Manager MasterChef 9 (FOX) - En demol Shine, 2017-2018 Casting Coordinator Project Runway 16 (Lifetime) - B unim/Murray, 2017 Casting Manager Emmy nominated for “Outstanding Casting For A Reality Program” Project Runway 15 (Lifetime) - B unim/Murray, 2016 Casting Manager Emmy nominated for “Outstanding Casting For A Reality Program” Bad Girls Club 15 (Oxygen) - Bunim/Murray, 2015 Casting Manager Project Runway 14 (Lifetime) - B unim/Murray, 2015 Casting Manager Project Runway 13 (Lifetime) - B unim/Murray, 2014 Casting Manager The Cure (ABC) - Bunim/Murray, 2014 Casting Manager Are You The One? 2 (MTV) - Lighthearted Entertainment, 2014 Casting Manager Dating Naked 2 (Vh1) - L ighthearted Entertainment, 2014 Casting Manager Project Runway 12 (Lifetime) - B unim/Murray, 2013 Casting Manager Don’t Give Up: There’s Always Hope (MTV) - Epic Junction, 2013 Casting Coordinator Project Runway: Under The Gunn (Lifetime) - Bunim/Murray, 2013 Casting Manager Q’Viva (Univision/FOX) - XIX Entertainment, 2012 Talent Coordinator I’m Having Their Baby 2 (Oxygen) - Epic Junction, 2012 Casting Coordinator Stars in Danger (FOX) - Bunim/Murray, 2012 Casting Manager Best Ink 2 (Oxygen) - B unim/Murray, -

They Called the Men Elite. This Year, They'll Call

Game on. They called the men elite. This year, they’ll call them champions. The women will continue their dominance as they defend and repeat. Game on. They called the men elite. This year, they’ll call them champions. The women will continue their dominance as they defend and repeat. FRIDAY | NOVEMBER 2, 2012 | the Sports B2 Baylor Lariat www.baylorlariat.com Whoop Baylor students have option of There it is front row hoops By Lindsey Miner The Bear Pit would typically Sports Reporter stand all game while yelling and How ready is Baylor Nation? distracting Baylor’s opponent with This basketball season, Baylor feisty cheers. The Bear Pit also put students better be prepared to lose on pep rallies before big games. their voices from excessive cheer- “If people get rid of the Bear Q ing, paint their bodies green and Pit, I hope they get rid of it be- gold. And earn some camera time cause it becomes too big to man- with Alexa Brackin and Lindsey Miner at the men’s and women’s basket- age,” Friedman said. A ball games at the Ferrell Center. The bill passed by Baylor Sen- The sections behind the bas- ate last semester recommended The Lariat sports reporters went around the Baylor campus and asked kets, typically reserved for mem- that anyone in the student body bers of the Bear Pit, will be open should be privy to those court students questions about the upcoming basketball season. to all students on a first-come, seats. After last season’s excite- first-served basis. -

WBC Bios Small

WOM EN’S DRC BUSINESS CONFERENCE PRESENTED BY KEYNOTE Stacy London STYLIST/TV PERSONALITY Stacy London is one of America's foremost fashion experts. She is best known as the co-host of TLC's hugely popular show, “What Not To Wear,” as well as the natural gray streak in her hair, which appeared at age 11. Her first book, “Dress Your Best,” concentrates on style by body type and was published to stellar reviews. Her second book, “The Truth About Style,” a New York Times bestseller, is both a memoir and a style guide. In “The Truth About Style,” London shares her story and focuses on the healing power of personal style and using that expertise to overcome past problems. A native Manhattanite, London graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Vassar College with an independent degree in philosophy and German literature. From 2005-10, London joined “The Today Show” on NBC as a style correspondent and has regularly appeared on “Access Hollywood.” Prior to her career in television, she started at Vogue as a fashion assistant and later returned to Conde Nast as the Senior Fashion Editor at Mademoiselle. London has styled fashion photos for publications such as Italian D, Nylon, and Contents, and has dressed many celebrities, including Kate Winslet, Katie Holmes, and Liv Tyler. Rebecca Taylor, Vivienne Tam, and Ghost have all used her as a consultant on their fashion shows. London was recently made a Style Contributor to “The View.” London has appeared on numerous national talk and news shows including “Oprah,” CNN, CBS' “The Early Show,” and MSNBC. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Contact: March 31, 2015 Joanna Brahim, 212-548-5005 Joanna [email protected] Press Materials

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Contact: March 31, 2015 Joanna Brahim, 212-548-5005 [email protected] Press materials: http://press.discovery.com/tlc/ TLC FILLS OUT 2015-2016 SLATE OF PROGRAMMING WITH STYLE, UNIQUE FAMILIES, AND LIFE’S MOST IMPORTANT MOMENTS (New York, NY) - TLC wrapped up 2014 with 30 hit series averaging over 1M viewers and record-breaking numbers for beloved hit series, and the network continues that momentum into 2015. In January, viewers fell in love with TLC’s newest personality, Whitney Thore with MY BIG FAT FABULOUS LIFE, and the network dove right back into the style genre with the highly anticipated return of Stacy London in the new series LOVE, LUST OR RUN. In February, 19 KIDS AND COUNTING returned with its highest rated season premiere, continuing to follow the ever-growing Duggar family. This mix of authentic real people, compelling transformation, and larger-than-life stories will drive the network forward in the coming year. “TLC’s mission is to find the relatable in the extraordinary, the heart in the unfamiliar, the quiet connection in a hectic world. This year, we dig deeper into our brand to deliver bigger moments and remarkable people that make this network a destination for millions of viewers,” said Marjorie Kaplan, Group President, TLC & Animal Planet. Today’s television viewer is mobile, multi-tasking, and expecting to connect on a deeper level with the shows and characters they love. Pairing with the network’s on-air success, TLC connects with its fans across multiple platforms, extending the conversation beyond the TV screen and into the always-on lives of its viewers. -

From #Boycottfashion to #Lovedclotheslast

From #BoycottFashion To #LovedClothesLast Understanding the Impact of the Sustainable Activist Consumer and How Activist Movements are Shaping a Circular Fashion Industry Hilary Jade Ip Final Fashion Management Project sustainable noun able to be maintained at a certain rate or level activist noun a person who campaigns to bring about political or social change consumer noun a person who purchases goods and services for personal use. FINAL FASHION MANAGEMENT PROJECT WORD COUNT: 7050 STUDENT ID: 29483816 This report has been printed on 100% recycled paper CONTENTS 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8 INTRODUCTION 10 METHODOLOGY 12 CHAPTER 1: FASHION ACTIVISM 25 CHAPTER 2: THE ACTIVIST CONSUMER 32 CHAPTER 3: THE CURRENT INDUSTRY RESPONSE 44 CHAPTER 4: THE CIRCULAR ECONOMY 50 CHAPTER 5: RECOMMENDATION 58 CHAPTER 6: POST COVID-19 64 CONCLUSION 67 APPENDIX 76 BIBLIOGRAPHY 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report provides an investigative analysis of the ‘sustainable’ activist consumer and how activist movements have pushed the fashion industry towards a more circular future. Chapter 1 of the report analyses the fashion activism and its current forms in the digital age. It examines the impact of activist movements focusing on disrupting fashion consumption. Chapter 2 of the report dissects the Generation Z (Gen Z) activist consumer. Gen Z stands to become one of the most influential consumer “The Fashion Industry is groups and is leading the current industry shift. Chapter 3 of the report explores the response of fashion industry, examining notable examples from across the fashion hierarchy and the Broken” potential issues with their strategies. - Chapter 4 of the report introduces the Circular Economy model, a radical Clare Farrell, change option for brands to improve their Corporate Social Responsibility that is not the Triple Bottom Line.