Chapter 21.Qxp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae C

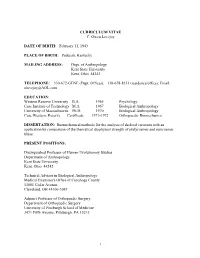

CURRICULUM VITAE C. Owen Lovejoy DATE OF BIRTH: February 11, 1943 PLACE OF BIRTH: Paducah, Kentucky MAILING ADDRESS: Dept. of Anthropology Kent State University Kent, Ohio 44242 TELEPHONE: 330-672-GENE (Dept. Offices); 330-678-8351 (residence/office); Email: [email protected] EDUCATION: Western Reserve University B.A. 1965 Psychology Case Institute of Technology M.A. 1967 Biological Anthropology University of Massachusetts Ph.D. 1970 Biological Anthropology Case Western. Reserve. Certificate 1971-1972 Orthopaedic Biomechanics DISSERTATION: Biomechanical methods for the analysis of skeletal variation with an application by comparison of the theoretical diaphyseal strength of platycnemic and euricnemic tibias. PRESENT POSITIONS: Distinguished Professor of Human Evolutionary Studies Department of Anthropology Kent State University Kent, Ohio 44242 Technical Advisor in Biological Anthropology Medical Examiner's Office of Cuyahoga County 11001 Cedar Avenue Cleveland, OH 44106-3043 Adjunct Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery Department of Orthopaedic Surgery University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine 3471 Fifth Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15213 1 Research Associate The Cleveland Museum of Natural History 1 Wade Oval Cleveland Ohio, 44106 GENERAL PREPARED COURSES: Human Gross Anatomy Skeletal Biomechanics (statics and dynamics) Principles of Biological Anthropology Mammalian Musculoskeletal System Development and Evolution of the mammalian limb Plio/Pleistocene Hominid Morphology Human Osteology Forensic Anthropology Mammalian Palaeodemography Human -

Children and Sustainable Development: a Challenge for Education

THE PONTIFICAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WORKSHOP ON Children and Sustainable Development: A Challenge for Education 13-15 November 2015 • Casina Pio IV • Vatican City The Canticle of the Sun Francis oF assisi Most high, all powerful, all good Lord! all praise is yours, all glory, all honor, and all blessing. To you, alone, Most High, do they belong. no mortal lips are worthy to pronounce your name. Be praised, my Lord, through all your creatures, especially through my lord “ Brother sun, who brings the day; and you give light through him. and he is beautiful and radiant in all his splendor! of you, Most High, he bears the likeness. Be praised, my Lord, through sister Moon and the stars; in the heavens you have made them, precious and beautiful. Be praised, my Lord, through Brothers Wind and air, and clouds and storms, and all the weather, through which you give your creatures sustenance. Be praised, My Lord, through sister Water; she is very useful, and humble, and precious, and pure. Be praised, my Lord, through Brother Fire, through whom you brighten the night. He is beautiful and cheerful, and powerful and strong. Be praised, my Lord, through our sister Mother Earth, who feeds us and rules us, and produces various fruits with colored flowers and herbs. Be praised, my Lord, through those who forgive for love of you; through those who endure sickness and trial. Happy those who endure in peace, for by you, Most High, they will be crowned. Be praised, my Lord, through our sister Bodily Death, from whose embrace no living person can escape. -

Lucy’’ Redux: a Review of Research on Australopithecus Afarensis

YEARBOOK OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 52:2–48 (2009) ‘‘Lucy’’ Redux: A Review of Research on Australopithecus afarensis William H. Kimbel* and Lucas K. Delezene Institute of Human Origins, School of Human Evolution and Social Change, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287-4101 KEY WORDS Australopithecus afarensis; Hadar; Laetoli; Pliocene hominin evolution ABSTRACT In the 1970s, mid-Pliocene hominin fossils methodology in paleoanthropology; in addition, important were found at the sites of Hadar in Ethiopia and Laetoli in fossil and genetic discoveries were changing expectations Tanzania. These samples constituted the first substantial about hominin divergence dates from extant African apes. evidence for hominins older than 3.0 Ma and were notable This coincidence of events ensured that A. afarensis figured for some remarkable discoveries, such as the ‘‘Lucy’’ partial prominently in the last 30 years of paleoanthropological skeleton and the abundant remains from the A.L. 333 local- research. Here, the 301 year history of discovery, analysis, ity at Hadar and the hominin footprint trail at Laetoli. The and interpretation of A. afarensis and its contexts are sum- Hadar and Laetoli fossils were ultimately assigned to the marized and synthesized. Research on A. afarensis contin- novel hominin species Australopithecus afarensis, which at ues and subject areas in which further investigation is the time was the most plesiomorphic and geologically an- needed to resolve ongoing debates regarding the paleobiol- cient hominin taxon. The discovery and naming of A. afar- ogy of this species are highlighted. Yrbk Phys Anthropol ensis coincided with important developments in theory and 52:2–48, 2009. VC 2009 Wiley-Liss, Inc. -

Responding to the Pandemic, Lessons for Future Actions and Changing Priorities

Responding to the Pandemic, Lessons for Future Actions and Changing Priorities The Vatican, Casina Pio IV on March 20, 2020 A Statement by the Pontifical Academy of Sciences and the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences In view of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Pontifical Academies of Sciences and of Social Sciences issue this communication. We note with great appreciation the tremendous services currently provided by health workers and medical professionals, including virologists and others. COVID-19 is a challenge for societies, their health systems, and economies, and especially for directly and indirectly affected people and their families. In the history of humanity, pandemics have always been tragic and have often been deadlier than wars. Today thanks to science, our knowledge is more advanced and can increasingly defend us against new forms of pandemics. Our statement intends to focus on science, science policy, and health policy actions in a broader societal context. We draw attention to the need for action, short- and long-term lessons, and future adjustments of priorities with these five points: 1. Strengthening early action and early responses: Health systems need to be strengthened in all countries. The need for early warning and early response is a lesson learned so far from the COVID-19 crisis. It is vitally important to get ahead of the curve in dealing with such global crises. We emphasize that public health measures must be initiated instantaneously in every country to combat the continuing spread of this virus. The need for testing at scale must be recognized and acted upon, and people who test positive for COVID-19 must be quarantined, along with their close contacts.We received advance warning of the outbreak a few months before it hit us on a global scale. -

Science and Human Origins

Science and Human Origins Science and Human Origins A NN G AUGER DOUGLAS AXE CASEY LUSKIN Seattle Discovery Institute Press 2012 Description Evidence for a purely Darwinian account of human origins is supposed to be overwhelming. But is it? In this provocative book, three scientists challenge the claim that undirected natural selection is capable of building a human being, critically assess fossil and genetic evidence that human beings share a common ancestor with apes, and debunk recent claims that the human race could not have started from an original couple. Copyright Notice Copyright © 2012 by Discovery Institute and the respective authors. All Rights Reserved. Publisher’s Note This book is part of a series published by the Center for Science & Culture at Discovery Institute in Seattle. Previous books include The Deniable Darwin by David Berlinski, In the Beginning and Other Essays on Intelligent Design by Granville Sewell, Alfred Russel Wallace: A Rediscovered Life by Michael Flannery, The Myth of Junk DNA by Jonathan Wells, and Signature of Controversy, edited by David Klinghoffer. Library Cataloging Data Science and Human Origins by Ann Gauger, Douglas Axe, and Casey Luskin Illustrations by Jonathan Aaron Jones and others as noted. 124 pages Library of Congress Control Number: 2012934836 BISAC: SCI027000 SCIENCE / Life Sciences / Evolution BISAC: SCI029000 SCIENCE / Life Sciences / Genetics & Genomics ISBN-13: 978-1-936599-04-2 (paperback) Publisher Information Discovery Institute Press, 208 Columbia Street, Seattle, WA 98104 Internet: http://www.discoveryinstitutepress.com/ Published in the United States of America on acid-free paper. First Edition, First Printing: April 2012. Cover Design: Brian Gage Interior Layout: Michael W. -

A New Species of the Genus Australopithecus (Primates: Hominidae) from the ' Pliocene of Eastern Africa

® THE CLEVELAND MUS E UM OF N ATU R AL HISTORY CLEVELAND, OHIO NUMBER 28 A NEW SPECIES OF THE GENUS AUSTRALOPITHECUS (PRIMATES: HOMINIDAE) FROM THE ' PLIOCENE OF EASTERN AFRICA DONALD C. JOHANSON Curator of Physical Anthropology The Cleveland Museum of Natural History Cleveland, Ohio TIM D. WHITE Department of Anthropology University of California-Berkeley Berkeley, California YVES COPPENS Directeur Laboratoire d' Anthropologie Musee de I 'Homme Paris, France 0015-6245178 1 1978-0028 $00.701o 2 D. JOHANSON ET AL. No. 28 ABSTRACT Hominid fossils have recently been recovered from Pliocene age deposits at Hadar, Ethiopia, and Laetolil, Tanzania. These fossils share an array of distinctive morphological characteristics which suggests that they belong to a single species of the genusAustralopithecus, differing significantly from those previously described. The binomen Australopithecus afarensis sp. nov. is therefore assigned to this collection of early hominid remains. A substantial collection of hominid fossils has recently been recovered from two Pliocene sites in eastern Africa. Hominid specimens from Hadar in Ethiopia (11 °N, 40°30'E) and Laetolil in Tanzania (3°12'S, 35°11 'E) have been dated to between ca. 2. 9 and ca. 3. 7 million years before present (Aronson· et al., 1977; Leakey et al ., 1977). The strong morphological continuity be tween these two samples suggests that they are best considered as representing a single taxon; hence, the Hadar and Laetolil fossils currently constitute the oldest indisputable evidence of the family Hominidae. Some of these specimens have been provisionally allocated to Homo sp. indet. (Johanson and Taieb, 1976; Leakey et al., 1977) while others have been referred to Australopithecus aff. -

Adaptive Radiation of the Plio-Pleistocene Hominids : an Ecological Approach

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1991 Adaptive radiation of the Plio-Pleistocene hominids : An ecological approach Patrick Light The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Light, Patrick, "Adaptive radiation of the Plio-Pleistocene hominids : An ecological approach" (1991). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 7310. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/7310 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY Copying allowed as provided under provisions of the Fair Use Section of the U.S. COPYRIGHT LAW, 1976. Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author’s written consent. University of Montana Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. The Adaptive Radiation of the Plio-Pleistocene Hominids: An Ecological Approach By Patrick Light B. A., Ohio State University, 1973 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Montana 1991 Approved by: Chair, Board of^^x^miners Dean, Graduate schoo1 /6. / f f / Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Ancestor`S Tale (Dawkins).Pdf

THE ANCESTOR'S TALE By the same author: The Selfish Gene The Extended Phenotype The Blind Watchmaker River Out of Eden Climbing Mount Improbable Unweaving the Rainbow A Devil's Chaplain THE ANCESTOR'S TALE A PILGRIMAGE TO THE DAWN OF LIFE RICHARD DAWKINS with additional research by YAN WONG WEIDENFELD & NICOLSON John Maynard Smith (1920-2004) He saw a draft and graciously accepted the dedication, which now, sadly, must become In Memoriam 'Never mind the lectures or the "workshops"; be Mowed to the motor coach excursions to local beauty spots; forget your fancy visual aids and radio microphones; the only thing that really matters at a conference is that John Maynard Smith must be in residence and there must be a spacious, convivial bar. If he can't manage the dates you have in mind, you must just reschedule the conference.. .He will charm and amuse the young research workers, listen to their stories, inspire them, rekindle enthusiasms that might be flagging, and send them back to their laboratories or their muddy fields, enlivened and invigorated, eager to try out the new ideas he has generously shared with them.' It isn't only conferences that will never be the same again. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I was persuaded to write this book by Anthony Cheetham, founder of Orion Books. The fact that he had moved on before the book was published reflects my unconscionable delay in finishing it. Michael Dover tolerated that delay with humour and fortitude, and always encouraged me by his swift and intelligent understanding of what I was trying to do. -

FLASHCARDS > Genera Australopithecus and Paranthropus

FLASHCARDS > Genera Australopithecus and Paranthropus There are over five known species in the genus Australopithecus and at least three known species in the genus Paranthropus. It is essential, when learning about Human evolution, to know the traits that are used to identify the different hominin fossil species. These flashcards will help you learn about the significance of some of the most well-known fossils, and their identifying traits. Instructions for Printing Flashcards: 1. Print on both sides of one piece of paper, preferably cardstock or other heavy-weight paper. For best results, use the “duplex” or two-sided printing option. Or flip the paper after printing the first side. 2. After printing the first side, flip the paper over and feed back into the printer. The cards are formatted to print the correct information on the appropriate side of the card. • Note: using a higher printing resolution will improve the quality of the images. 3. Cut out the flashcards along the borders. 4. Have fun and learn! This set includes the fossil hominins: • AL-288, “Lucy” • “Taung Child” • OH 5, “Nutcracker Man” • KNM-WT 17000, “The Black Skull” ©eFOSSILS 2007 www.eFossils.org and www.eLucy.org FLASHCARDS > Genera Australopithecus and Paranthropus This page intentionally left blank. ©eFOSSILS 2007 www.eFossils.org and www.eLucy.org AL 288-1 “Taung Child” OH 5 KNM-WT 17000 1 “Taung Child” AL 288-1 Australopithecus africanus Australopithecus afarensis Nickname: “Lucy” Discovery Who: Raymond Dart Discovery Where: Taung, South Africa Who: Donald Johanson, Yves Coppens When: 1924 and Tim White Where: The Hadar Site, Afar Region, Ethiopia Fossil When: November 24, 1974 Geological Age: ~3-<2.5 million years Age: Juvenile, 3-5 years old Fossil Brain Capacity: 410 cubic centimeters Geological Age: 3.2 million years (440 cc as an adult) Sex: Female Age: Adult, 25 years Notables Stature: 107 centimeters (3’6”) • The first Australopithecine discovered Weight: 28 kilograms (65 lbs) • Well preserved endocranial cast of the brain. -

Final Statement of the 2020 PAS Plenary Session

Final Statement of the 2020 PAS Plenary Session Science and Survival – A focus on SARS-CoV-2, connections between large-scale risks for life on this planet and opportunities of science to address them Plenary Session October 7-9, and 28, 2020 Worldviews, perspectives and science 1. The 2020 PAS Plenary Session was guided by the idea that the role of science is critical for the survival of humanity – in view of the SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 crisis probably more so than ever. The conference also addressed interlinkages between health, large-scale risks for people, and planetary health, as well as opportunities of science to tackle and contribute to solving them. The 2020 Plenary builds on deliberations by the Pontifical Academy of Sciences earlier this year that led to a joint statement by the Pontifical Academy of Sciences and the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences. A lot has been learned about the pandemic in the past year, and scientists need to share and systematically compare insights. 2. Scientific evidence has a strong impact on political decisions at a global scale. Examples are the prediction that a nuclear war would cause a nuclear winter; the discovery of the reasons for the ozone hole and the analysis of its deleterious effects on life by Mario Molina and Paul Crutzen; the discovery of the reasons for global warming and the predictions of its devastating effects; the quantification of the exponential rate of species extinction that jeopardizes the equilibrium of our biosphere. It is noteworthy that all of these problems are man- made and came into the world because of the inappropriate use of advances of science and technology. -

Hominid Evolution and the Emergence of the Genus Homo

Neurosciences and the Human Person: New Perspectives on Human Activities Pontifical Academy of Sciences, Scripta Varia 121, Vatican City 2013 www.casinapioiv.va/content/dam/accademia/pdf/sv121/sv121-coppens.pdf Hominid evolution and the emergence of the genus Homo Yves Coppens I am very happy and much honoured to have been invited, for the third time, to this famous Academy, for a new working group. If I understood well, my duty, here, is to give you the state of art of palaeoanthropology, the current way of understanding, with bones and teeth, the history of Man, of his close relatives and of his closest ancestors. I will try to do that. *** Let us remember, for the pleasure, that Man is a living being, an eucaryot, a metazoaires, a chordate, a vertebrate, a gnathostom, a sarcopterygian, a tetrapod, an amniot, a synapsid, a mammal, a primate, an Haplorhinian, a Simiiform, a Catarrhinian, an Hominoidea, an Hominidae, an Homininae and that life, on earth, is around 4 billion years old, metazoaires, 2 billion years old, vertebrates, 535 million years old, gnathostoms, 420 million years old, mammals, 230 million years old, Primates, 70 million years old, Homi- noidea, 50 million years old, Hominidae, 10 million years old. And let us remember also that Primates, adapted to arboricolism and frugivory, developed three flourishing branches worldwide all over the trop- ics: the Plesiadapiforms, the Strepsirhinians composed of Adapiforms and Lemuriforms, and the Haplorhinians, composed of Tarsiiforms and Simi- iforms, and that the Hominoidea are a superfamily of the Simiiforms, born in Eastern Asia, fifty million years ago, as I mentioned above. -

Conference Booklet

THE PONTIFICAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES THE PONTIFICAL ACADEMY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Joint Workshop Sustainable Humanity Sustainable Nature Our Responsibility 2-6 May 2014 • Casina Pio IV VatICan CIty 2014 today no one in our world feels responsible; we have lost a sense of responsibility for our brothers and sisters. We have fallen into the hypocrisy of the priest and the levite whom Jesus described in the parable of the Good Samaritan: we see our bro - ther half dead on the side of the road, and perhaps we say to ourselves: “poor soul… !”, and then go on our way. It’s not our responsibility, and with that we feel reassu - red, assuaged. the culture of comfort, which makes us think only of ourselves, makes us insensitive to the cries of other people, makes us live in soap bubbles which, however lovely, are insubstantial; they offer a fleeting and empty illusion which results in indifference to others; indeed, it even leads to the globalization of indifference. … “adam, where are you?” “Where is your brother?” these are the two questions which God asks at the dawn of human history, and which he also asks each man and woman in our own day. today too, Lord, we hear you asking: “adam, where are you?” “Where is the blood of your brother?”. Homily of Holy Father Francis during his visit to Lampedusa, “arena” sports camp, Salina Quarter, Monday, 8 July 2013. Sustainable Humanity Sustainable Nature Our Responsibility INTRODUCTION re Humanity's dealings with nature sus - lems” and “future prospects” present themselves tainable? What is the status of the Human in different ways to different people.