To Call Our Own

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae C

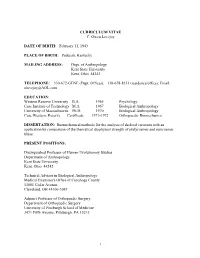

CURRICULUM VITAE C. Owen Lovejoy DATE OF BIRTH: February 11, 1943 PLACE OF BIRTH: Paducah, Kentucky MAILING ADDRESS: Dept. of Anthropology Kent State University Kent, Ohio 44242 TELEPHONE: 330-672-GENE (Dept. Offices); 330-678-8351 (residence/office); Email: [email protected] EDUCATION: Western Reserve University B.A. 1965 Psychology Case Institute of Technology M.A. 1967 Biological Anthropology University of Massachusetts Ph.D. 1970 Biological Anthropology Case Western. Reserve. Certificate 1971-1972 Orthopaedic Biomechanics DISSERTATION: Biomechanical methods for the analysis of skeletal variation with an application by comparison of the theoretical diaphyseal strength of platycnemic and euricnemic tibias. PRESENT POSITIONS: Distinguished Professor of Human Evolutionary Studies Department of Anthropology Kent State University Kent, Ohio 44242 Technical Advisor in Biological Anthropology Medical Examiner's Office of Cuyahoga County 11001 Cedar Avenue Cleveland, OH 44106-3043 Adjunct Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery Department of Orthopaedic Surgery University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine 3471 Fifth Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15213 1 Research Associate The Cleveland Museum of Natural History 1 Wade Oval Cleveland Ohio, 44106 GENERAL PREPARED COURSES: Human Gross Anatomy Skeletal Biomechanics (statics and dynamics) Principles of Biological Anthropology Mammalian Musculoskeletal System Development and Evolution of the mammalian limb Plio/Pleistocene Hominid Morphology Human Osteology Forensic Anthropology Mammalian Palaeodemography Human -

Late Miocene Hominid from Chad) Cranium

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Harvard University - DASH Morphological Affinities of the Sahelanthropus Tchadensis (Late Miocene Hominid from Chad) Cranium The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Guy, Franck, Daniel E. Lieberman, David Pilbeam, Marcia Ponce de Leon, Andossa Likius, Hassane T. Mackaye, Patrick Vignaud, Christoph Zollikofer, and Michel Brunet. 2005. Morphological affinities of the Sahelanthropus tchadensis (Late Miocene hominid from Chad) cranium. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102(52): 18836–18841. Published Version doi:10.1073/pnas.0509564102 Accessed February 18, 2015 9:32:20 AM EST Citable Link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:3716604 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University's DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms- of-use#LAA (Article begins on next page) Morphological affinities of the Sahelanthropus tchadensis (Late Miocene hominid from Chad) cranium Franck Guy*, Daniel E. Lieberman†, David Pilbeam†‡, Marcia Ponce de Leo´ n§, Andossa Likius¶, Hassane T. Mackaye¶, Patrick Vignaud*, Christoph Zollikofer§, and Michel Brunet*‡ *Laboratoire de Ge´ obiologie, Biochronologie et Pale´ ontologie Humaine, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique -

Many Ways of Being Human, the Stephen J. Gould's Legacy To

doi 10.4436/JASS.90016 JASs Historical Corner e-pub ahead of print Journal of Anthropological Sciences Vol. 90 (2012), pp. 1-18 Many ways of being human, the Stephen J. Gould’s legacy to Palaeo-Anthropology (2002-2012) Telmo Pievani University of Milan Bicocca, Piazza Ateneo Nuovo, 1 - 20126 Milan, Italy e-mail: [email protected] Summary - As an invertebrate palaeontologist and evolutionary theorist, Stephen J. Gould did not publish any direct experimental results in palaeo-anthropology (with the exception of Pilbeam & Gould, 1974), but he did prepare the stage for many debates within the discipline. We argue here that his scientific legacy in the anthropological fields has a clear and coherent conceptual structure. It is based on four main pillars: (1) the famed deconstruction of the “ladder of progress” as an influential metaphor in human evolution; (2) Punctuated Equilibria and their significance in human macro-evolution viewed as a directionless “bushy tree” of species; (3) the trade-offs between functional and structural factors in evolution and the notion of exaptation; (4) delayed growth, or neoteny, as an evidence in human evolution. These keystones should be considered as consequences of the enduring theoretical legacy of the eminent Harvard evolutionist: the proposal of an extended and revised Darwinism, coherently outlined in the last twenty years of his life (1982–2002) and set out in 2002 in his final work, The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. It is in the light of his “Darwinian pluralism”, able to integrate in a new frame the multiplicity of explanatory patterns emerging from different evolutionary fields, that we understand Stephen J. -

Transitions in Prehistory Essays in Honor of Ofer Bar-Yosef

Transitions in Prehistory Essays in Honor of Ofer Bar-Yosef Oxbow Books Oxford and Oakville AMERICAN SCHOOL OF PREHISTORIC RESEARCH MONOGRAPH SERIES Series Editors C. C. LAMBERG-KARLOVSKY, Harvard University DAVID PILBEAM, Harvard University OFER BAR-YOSEF, Harvard University Editorial Board STEVEN L. KUHN, University of Arizona, Tucson DANIEL E. LIEBERMAN, Harvard University RICHARD H. MEADOW, Harvard University MARY M. VOIGT, The College of William and Mary HENRY T. WRIGHT, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Publications Coordinator WREN FOURNIER, Harvard University The American School of Prehistoric Research (ASPR) Monographs in Archaeology and Paleoanthropology present a series of documents covering a variety of subjects in the archaeology of the Old World (Eurasia, Africa, Australia, and Oceania). This series encompasses a broad range of subjects – from the early prehistory to the Neolithic Revolution in the Old World, and beyond including: hunter- gatherers to complex societies; the rise of agriculture; the emergence of urban societies; human physi- cal morphology, evolution and adaptation, as well as; various technologies such as metallurgy, pottery production, tool making, and shelter construction. Additionally, the subjects of symbolism, religion, and art will be presented within the context of archaeological studies including mortuary practices and rock art. Volumes may be authored by one investigator, a team of investigators, or may be an edited collec- tion of shorter articles by a number of different specialists working on related topics. American School of Prehistoric Research, Peabody Museum, Harvard University, 11 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA Transitions in Prehistory Essays in Honor of Ofer Bar-Yosef Edited by John J. Shea and Daniel E. -

Children and Sustainable Development: a Challenge for Education

THE PONTIFICAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WORKSHOP ON Children and Sustainable Development: A Challenge for Education 13-15 November 2015 • Casina Pio IV • Vatican City The Canticle of the Sun Francis oF assisi Most high, all powerful, all good Lord! all praise is yours, all glory, all honor, and all blessing. To you, alone, Most High, do they belong. no mortal lips are worthy to pronounce your name. Be praised, my Lord, through all your creatures, especially through my lord “ Brother sun, who brings the day; and you give light through him. and he is beautiful and radiant in all his splendor! of you, Most High, he bears the likeness. Be praised, my Lord, through sister Moon and the stars; in the heavens you have made them, precious and beautiful. Be praised, my Lord, through Brothers Wind and air, and clouds and storms, and all the weather, through which you give your creatures sustenance. Be praised, My Lord, through sister Water; she is very useful, and humble, and precious, and pure. Be praised, my Lord, through Brother Fire, through whom you brighten the night. He is beautiful and cheerful, and powerful and strong. Be praised, my Lord, through our sister Mother Earth, who feeds us and rules us, and produces various fruits with colored flowers and herbs. Be praised, my Lord, through those who forgive for love of you; through those who endure sickness and trial. Happy those who endure in peace, for by you, Most High, they will be crowned. Be praised, my Lord, through our sister Bodily Death, from whose embrace no living person can escape. -

Sherry Nelson Cv Webpage 2019

SHERRY V. NELSON September 2019 Department of Anthropology University of New Mexico MSC01-1040, 1 University of New Mexico Albuquerque, NM [email protected] http://svnelson.wix.com/svnelson Education 2002 Harvard University, Ph.D. Anthropology, (“Faunal and Environmental Change Surrounding the Extinction of Sivapithecus, a Miocene Hominoid, in the Siwaliks of Pakistan,” David Pilbeam, advisor) 1994 Duke University, B.S. Biology (with a concentration in evolutionary biology) / Biological Anthropology and Anatomy, cum laude Recent and Current Positions 2015-current Associate Professor, University of New Mexico, Department of Anthropology 2007-2015 Assistant Professor, University of New Mexico, Department of Anthropology 2005-2007 Assistant Professor, Boston University, Department of Anthropology 2004-2007 Department Affiliate, Harvard University, Department of Anthropology 2002-2004 Postdoctoral research associate, University of Michigan, Museum of Paleontology Grants, Fellowships, and Awards 2017 Resource Allocations Committee Grant, University of New Mexico, Modeling early human paleoecology through stable isotope analyses of chimpanzee habitats and forest stratification, $9,755 2016 Nominated, Outstanding Teacher of the Year, University of New Mexico 2015 Office of the Vice President of Research Equipment Fund, University of New Mexico, Equipment Request Paleoecology Laboratory, $15,000 2014-2017 National Science Foundation, Developmental integration and the ecology of life histories in phylogenetic perspective, M.N. Muller (PI), S.V. -

Harrison CV June 2021

June 1, 2021 Terry Harrison CURRICULUM VITAE CONTACT INFORMATION * Center for the Study of Human Origins Department of Anthropology 25 Waverly Place New York University New York, NY 10003-6790, USA 8 [email protected] ) 212-998-8581 WEB LINKS http://as.nyu.edu/faculty/terry-harrison.html https://wp.nyu.edu/csho/people/faculty/terry_harrison/ https://nyu.academia.edu/TerryHarrison http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4224-0152 zoobank.org:author:43DA2256-CF4D-476F-8EA8-FBCE96317505 ACADEMIC BACKGROUND Graduate: 1978–1982: Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Anthropology, University College London, London. Doctoral dissertation: Small-bodied Apes from the Miocene of East Africa. 1981–1982: Postgraduate Certificate of Education. Institute of Education, London University, London. Awarded with Distinction. Undergraduate: 1975–1978: Bachelor of Science. Department of Anthropology, University College London, London. First Class Honours. POSITIONS 2014- Silver Professor, Department of Anthropology, New York University. 2003- Director, Center for the Study of Human Origins, New York University. 1995- Professor, Department of Anthropology, New York University. 2010-2016 Chair, Department of Anthropology, New York University. 1995-2010 Associate Chair, Department of Anthropology, New York University. 1990-1995 Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology, New York University. 1984-1990 Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, New York University. HONORS & AWARDS 1977 Rosa Morison Memorial Medal and Prize, University College London. 1978 Daryll Forde Award, University College London. 1989 Golden Dozen Award for excellence in teaching, New York University. 1996 Golden Dozen Award for excellence in teaching, New York University. 2002 Distinguished Teacher Award, New York University. 2006 Fellow, American Association for the Advancement of Science. -

A Unique Middle Miocene European Hominoid and the Origins of the Great Ape and Human Clade

A unique Middle Miocene European hominoid and the origins of the great ape and human clade Salvador Moya` -Sola` a,1, David M. Albab,c, Sergio Alme´ cijac, Isaac Casanovas-Vilarc, Meike Ko¨ hlera, Soledad De Esteban-Trivignoc, Josep M. Roblesc,d, Jordi Galindoc, and Josep Fortunyc aInstitucio´Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avanc¸ats at Institut Catala`de Paleontologia (ICP) and Unitat d’Antropologia Biolo`gica (Dipartimento de Biologia Animal, Biologia Vegetal, i Ecologia), Universitat Auto`noma de Barcelona, Edifici ICP, Campus de Bellaterra s/n, 08193 Cerdanyola del Valle`s, Barcelona, Spain; bDipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Universita`degli Studi di Firenze, Via G. La Pira 4, 50121 Florence, Italy; cInstitut Catala`de Paleontologia, Universitat Auto`noma de Barcelona, Edifici ICP, Campus de Bellaterra s/n, 08193 Cerdanyola del Valle`s, Barcelona, Spain; and dFOSSILIA Serveis Paleontolo`gics i Geolo`gics, S.L. c/ Jaume I nu´m 87, 1er 5a, 08470 Sant Celoni, Barcelona, Spain Edited by David Pilbeam, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, and approved March 4, 2009 (received for review November 20, 2008) The great ape and human clade (Primates: Hominidae) currently sediments by the diggers and bulldozers. After 6 years of includes orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, and humans. fieldwork, 150 fossiliferous localities have been sampled from the When, where, and from which taxon hominids evolved are among 300-m-thick local stratigraphic series of ACM, which spans an the most exciting questions yet to be resolved. Within the Afro- interval of 1 million years (Ϸ12.5–11.3 Ma, Late Aragonian, pithecidae, the Kenyapithecinae (Kenyapithecini ؉ Equatorini) Middle Miocene). -

(Late Miocene Hominid from Chad) Cranium

Morphological affinities of the Sahelanthropus tchadensis (Late Miocene hominid from Chad) cranium Franck Guy*, Daniel E. Lieberman†, David Pilbeam†‡, Marcia Ponce de Leo´ n§, Andossa Likius¶, Hassane T. Mackaye¶, Patrick Vignaud*, Christoph Zollikofer§, and Michel Brunet*‡ *Laboratoire de Ge´obiologie, Biochronologie et Pale´ontologie Humaine, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique Unite´Mixte de Recherche 6046, Faculte´des Sciences, Universite´de Poitiers, 40 Avenue du Recteur Pineau, 86022 Poitiers Cedex, France; §Anthropologisches Institut, Universita¨t Zu¨rich-Irchel, Winterthurerstrasse 190, 8057 Zu¨rich, Switzerland; †Peabody Museum, Harvard University, 11 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138; and ¶Department de Pale´ontologie, Universite´deNЈDjamena, BP 1117, NЈDjamena, Republic of Chad Contributed by David Pilbeam, November 5, 2005 The recent reconstruction of the Sahelanthropus tchadensis cra- cross-sectional ontogenetic samples of Pan troglodytes (n ϭ 40), nium (TM 266-01-60-1) provides an opportunity to examine in Gorilla gorilla (n ϭ 41), and Homo sapiens (n ϭ 24) (see Table detail differences in cranial shape between this earliest-known 3, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS hominid, African apes, and other hominid taxa. Here we compare web site). In addition, we digitized as many of the same land- the reconstruction of TM 266-01-60-1 with crania of African apes, marks as possible on a sample of available relatively complete humans, and several Pliocene hominids. The results not only fossil hominid crania: the stereolithograhic replica of AL 444-2 confirm that TM 266-01-60-1 is a hominid but also reveal a unique (Australopithecus afarensis) (9); CT scans of Sts 5 and Sts 71 mosaic of characters. -

Lucy’’ Redux: a Review of Research on Australopithecus Afarensis

YEARBOOK OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 52:2–48 (2009) ‘‘Lucy’’ Redux: A Review of Research on Australopithecus afarensis William H. Kimbel* and Lucas K. Delezene Institute of Human Origins, School of Human Evolution and Social Change, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287-4101 KEY WORDS Australopithecus afarensis; Hadar; Laetoli; Pliocene hominin evolution ABSTRACT In the 1970s, mid-Pliocene hominin fossils methodology in paleoanthropology; in addition, important were found at the sites of Hadar in Ethiopia and Laetoli in fossil and genetic discoveries were changing expectations Tanzania. These samples constituted the first substantial about hominin divergence dates from extant African apes. evidence for hominins older than 3.0 Ma and were notable This coincidence of events ensured that A. afarensis figured for some remarkable discoveries, such as the ‘‘Lucy’’ partial prominently in the last 30 years of paleoanthropological skeleton and the abundant remains from the A.L. 333 local- research. Here, the 301 year history of discovery, analysis, ity at Hadar and the hominin footprint trail at Laetoli. The and interpretation of A. afarensis and its contexts are sum- Hadar and Laetoli fossils were ultimately assigned to the marized and synthesized. Research on A. afarensis contin- novel hominin species Australopithecus afarensis, which at ues and subject areas in which further investigation is the time was the most plesiomorphic and geologically an- needed to resolve ongoing debates regarding the paleobiol- cient hominin taxon. The discovery and naming of A. afar- ogy of this species are highlighted. Yrbk Phys Anthropol ensis coincided with important developments in theory and 52:2–48, 2009. VC 2009 Wiley-Liss, Inc. -

This Article Appeared in a Journal Published by Elsevier. the Attached

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright Author's personal copy Journal of Human Evolution 58 (2010) 147–154 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Human Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhevol A hominoid distal tibia from the Miocene of Pakistan Jeremy M. DeSilva a,*, Miche`le E. Morgan b, John C. Barry b,c, David Pilbeam b,c a Department of Anthropology, 232 Bay State Road, Boston University, Boston, MA 02215, United States b Peabody Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, United States c Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, United States article info abstract Article history: A distal tibia, YGSP 1656, from the early Late Miocene portion of the Chinji Formation in Pakistan is Received 6 April 2009 described. The fossil is 11.4 million years old and is one of only six postcranial elements now assigned to Accepted 4 November 2009 Sivapithecus indicus. Aspects of the articular surface are cercopithecoid-like, suggesting some pronograde locomotor activities. -

Responding to the Pandemic, Lessons for Future Actions and Changing Priorities

Responding to the Pandemic, Lessons for Future Actions and Changing Priorities The Vatican, Casina Pio IV on March 20, 2020 A Statement by the Pontifical Academy of Sciences and the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences In view of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Pontifical Academies of Sciences and of Social Sciences issue this communication. We note with great appreciation the tremendous services currently provided by health workers and medical professionals, including virologists and others. COVID-19 is a challenge for societies, their health systems, and economies, and especially for directly and indirectly affected people and their families. In the history of humanity, pandemics have always been tragic and have often been deadlier than wars. Today thanks to science, our knowledge is more advanced and can increasingly defend us against new forms of pandemics. Our statement intends to focus on science, science policy, and health policy actions in a broader societal context. We draw attention to the need for action, short- and long-term lessons, and future adjustments of priorities with these five points: 1. Strengthening early action and early responses: Health systems need to be strengthened in all countries. The need for early warning and early response is a lesson learned so far from the COVID-19 crisis. It is vitally important to get ahead of the curve in dealing with such global crises. We emphasize that public health measures must be initiated instantaneously in every country to combat the continuing spread of this virus. The need for testing at scale must be recognized and acted upon, and people who test positive for COVID-19 must be quarantined, along with their close contacts.We received advance warning of the outbreak a few months before it hit us on a global scale.