Hominid Evolution and the Emergence of the Genus Homo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Defining the Genus Homo

Defining the Genus Homo Mark Collard and Bernard Wood Contents Introduction ..................................................................................... 2108 Changing Interpretations of Genus Homo ..................................................... 2109 Is Genus Homo a “Good” Genus? ............................................................. 2114 Updating Wood and Collard’s (1999) Review of Genus Homo .............................. 2126 Conclusion ...................................................................................... 2137 Cross-References ............................................................................... 2138 References ...................................................................................... 2138 Abstract The definition of the genus Homo is an important but under-researched topic. In this chapter we show that interpretations of Homo have changed greatly over the last 150 years as a result of the incorporation of new fossil species, the discovery of fossil evidence that changed our perceptions of its component species, and reassessments of the functional capabilities of species previously allocated to Homo. We also show that these changes have been made in an ad hoc fashion. Criteria for recognizing fossil specimens of Homo have been outlined on a M. Collard (*) Human Evolutionary Studies Program and Department of Archaeology, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada Department of Archaeology, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, UK e-mail: [email protected] B. Wood Center for the Advanced -

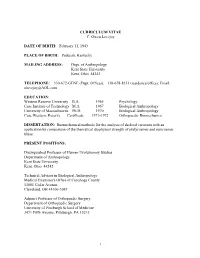

Curriculum Vitae C

CURRICULUM VITAE C. Owen Lovejoy DATE OF BIRTH: February 11, 1943 PLACE OF BIRTH: Paducah, Kentucky MAILING ADDRESS: Dept. of Anthropology Kent State University Kent, Ohio 44242 TELEPHONE: 330-672-GENE (Dept. Offices); 330-678-8351 (residence/office); Email: [email protected] EDUCATION: Western Reserve University B.A. 1965 Psychology Case Institute of Technology M.A. 1967 Biological Anthropology University of Massachusetts Ph.D. 1970 Biological Anthropology Case Western. Reserve. Certificate 1971-1972 Orthopaedic Biomechanics DISSERTATION: Biomechanical methods for the analysis of skeletal variation with an application by comparison of the theoretical diaphyseal strength of platycnemic and euricnemic tibias. PRESENT POSITIONS: Distinguished Professor of Human Evolutionary Studies Department of Anthropology Kent State University Kent, Ohio 44242 Technical Advisor in Biological Anthropology Medical Examiner's Office of Cuyahoga County 11001 Cedar Avenue Cleveland, OH 44106-3043 Adjunct Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery Department of Orthopaedic Surgery University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine 3471 Fifth Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15213 1 Research Associate The Cleveland Museum of Natural History 1 Wade Oval Cleveland Ohio, 44106 GENERAL PREPARED COURSES: Human Gross Anatomy Skeletal Biomechanics (statics and dynamics) Principles of Biological Anthropology Mammalian Musculoskeletal System Development and Evolution of the mammalian limb Plio/Pleistocene Hominid Morphology Human Osteology Forensic Anthropology Mammalian Palaeodemography Human -

Homo Habilis

COMMENT SUSTAINABILITY Citizens and POLICY End the bureaucracy THEATRE Shakespeare’s ENVIRONMENT James Lovelock businesses must track that is holding back science world was steeped in on surprisingly optimistic governments’ progress p.33 in India p.36 practical discovery p.39 form p.41 The foot of the apeman that palaeo ‘handy man’, anthropologists had been Homo habilis. recovering in southern Africa since the 1920s. This, the thinking went, was replaced by the taller, larger-brained Homo erectus from Asia, which spread to Europe and evolved into Nean derthals, which evolved into Homo sapiens. But what lay between the australopiths and H. erectus, the first known human? BETTING ON AFRICA Until the 1960s, H. erectus had been found only in Asia. But when primitive stone-chop LIBRARY PICTURE EVANS MUSEUM/MARY HISTORY NATURAL ping tools were uncovered at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, Leakey became convinced that this is where he would find the earliest stone- tool makers, who he assumed would belong to our genus. Maybe, like the australopiths, our human ancestors also originated in Africa. In 1931, Leakey began intensive prospect ing and excavation at Olduvai Gorge, 33 years before he announced the new human species. Now tourists travel to Olduvai on paved roads in air-conditioned buses; in the 1930s in the rainy season, the journey from Nairobi could take weeks. The ravines at Olduvai offered unparalleled access to ancient strata, but field work was no picnic in the park. Water was often scarce. Leakey and his team had to learn to share Olduvai with all of the wild animals that lived there, lions included. -

Hands-On Human Evolution: a Laboratory Based Approach

Hands-on Human Evolution: A Laboratory Based Approach Developed by Margarita Hernandez Center for Precollegiate Education and Training Author: Margarita Hernandez Curriculum Team: Julie Bokor, Sven Engling A huge thank you to….. Contents: 4. Author’s note 5. Introduction 6. Tips about the curriculum 8. Lesson Summaries 9. Lesson Sequencing Guide 10. Vocabulary 11. Next Generation Sunshine State Standards- Science 12. Background information 13. Lessons 122. Resources 123. Content Assessment 129. Content Area Expert Evaluation 131. Teacher Feedback Form 134. Student Feedback Form Lesson 1: Hominid Evolution Lab 19. Lesson 1 . Student Lab Pages . Student Lab Key . Human Evolution Phylogeny . Lab Station Numbers . Skeletal Pictures Lesson 2: Chromosomal Comparison Lab 48. Lesson 2 . Student Activity Pages . Student Lab Key Lesson 3: Naledi Jigsaw 77. Lesson 3 Author’s note Introduction Page The validity and importance of the theory of biological evolution runs strong throughout the topic of biology. Evolution serves as a foundation to many biological concepts by tying together the different tenants of biology, like ecology, anatomy, genetics, zoology, and taxonomy. It is for this reason that evolution plays a prominent role in the state and national standards and deserves thorough coverage in a classroom. A prime example of evolution can be seen in our own ancestral history, and this unit provides students with an excellent opportunity to consider the multiple lines of evidence that support hominid evolution. By allowing students the chance to uncover the supporting evidence for evolution themselves, they discover the ways the theory of evolution is supported by multiple sources. It is our hope that the opportunity to handle our ancestors’ bone casts and examine real molecular data, in an inquiry based environment, will pique the interest of students, ultimately leading them to conclude that the evidence they have gathered thoroughly supports the theory of evolution. -

Human Evolution: a Paleoanthropological Perspective - F.H

PHYSICAL (BIOLOGICAL) ANTHROPOLOGY - Human Evolution: A Paleoanthropological Perspective - F.H. Smith HUMAN EVOLUTION: A PALEOANTHROPOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE F.H. Smith Department of Anthropology, Loyola University Chicago, USA Keywords: Human evolution, Miocene apes, Sahelanthropus, australopithecines, Australopithecus afarensis, cladogenesis, robust australopithecines, early Homo, Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, Australopithecus africanus/Australopithecus garhi, mitochondrial DNA, homology, Neandertals, modern human origins, African Transitional Group. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Reconstructing Biological History: The Relationship of Humans and Apes 3. The Human Fossil Record: Basal Hominins 4. The Earliest Definite Hominins: The Australopithecines 5. Early Australopithecines as Primitive Humans 6. The Australopithecine Radiation 7. Origin and Evolution of the Genus Homo 8. Explaining Early Hominin Evolution: Controversy and the Documentation- Explanation Controversy 9. Early Homo erectus in East Africa and the Initial Radiation of Homo 10. After Homo erectus: The Middle Range of the Evolution of the Genus Homo 11. Neandertals and Late Archaics from Africa and Asia: The Hominin World before Modernity 12. The Origin of Modern Humans 13. Closing Perspective Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary UNESCO – EOLSS The basic course of human biological history is well represented by the existing fossil record, although there is considerable debate on the details of that history. This review details both what is firmly understood (first echelon issues) and what is contentious concerning humanSAMPLE evolution. Most of the coCHAPTERSntention actually concerns the details (second echelon issues) of human evolution rather than the fundamental issues. For example, both anatomical and molecular evidence on living (extant) hominoids (apes and humans) suggests the close relationship of African great apes and humans (hominins). That relationship is demonstrated by the existing hominoid fossil record, including that of early hominins. -

The Human Evolutionary Calendar - Evolution in a Year)I------1 January • December F------{( March ) ( June September

The Human Evolutionary Calendar - Evolution in a Year)I---------1 January • December f-------{( March ) ( June September SahelanthropusTchadensi Australopithecus sediba Homo rh odes iensis Ardipithecus ramidus 7,000,000 - 6,000,000 yrs. 2,000,000 - , ,750,000 yrs. 300,000 -125,000 yrs. 3,200,000 • 4,300,000 yrs. Homo rudolfensis Orrorin tugenensis 1,900,000 - 1.750,000 yrs. Homo pekin ensi s 6, 100,000 - 5,BOO,Oci:l yrs. 700,000 - 500,000 yrs. Australopit ec us anamensis 4,200,00 - 3,900,000 yrs. Ardipithecus kadabba 5,750,000 - 5,200,000 yrs. Ho m o Ergaster 1,900,000 - 1,3,000,000 yrs. Homo heidelberge nsis 700,000 • 200,000 yrs. Australopithecus afarensis Homo erectus 3,900,000 - 2,900,000 yrs. 1,800,000 • 250,000 yrs. Ho mo antecessor Australopithecus africa nus Ho mo habilis 1,000,000 -700,000 yrs. 3,800,000 - 3,000,000 yrs. 2,350,000 - 1,450,000 yrs. Ho m o g eorgicus Kenya nthropus platyo ps 1,800,000- 1.3000,000 yrs. 3,500,000 - 3,200,000 yrs. Ho m o nea nderthalensis 200,000 · 28,000 yrs. Paranthropus bo ise i Paranthropus aethiopicu 2,275,000- 1,250,000 yrs. De nisova ho minins 2,650,000 - 2,300,000 yrs. 200,000 - 30,000 yrs. Paranthropus robustus/crass iden s Australopithecus garhi 1,750,000- 1,200,000 yrs. 2,750,000 - 2.400,000 yrs. Red Deer Cave Peo ple ?- 11,000yrs. Ho mo sa piens sapien s 200~ Ho m o fl o res iensis 100,000 • 13,000 yrs. -

Paranthropus Boisei: Fifty Years of Evidence and Analysis Bernard A

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Biological Sciences Faculty Research Biological Sciences Fall 11-28-2007 Paranthropus boisei: Fifty Years of Evidence and Analysis Bernard A. Wood George Washington University Paul J. Constantino Biological Sciences, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/bio_sciences_faculty Part of the Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Wood B and Constantino P. Paranthropus boisei: Fifty years of evidence and analysis. Yearbook of Physical Anthropology 50:106-132. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Biological Sciences at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biological Sciences Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. YEARBOOK OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 50:106–132 (2007) Paranthropus boisei: Fifty Years of Evidence and Analysis Bernard Wood* and Paul Constantino Center for the Advanced Study of Hominid Paleobiology, George Washington University, Washington, DC 20052 KEY WORDS Paranthropus; boisei; aethiopicus; human evolution; Africa ABSTRACT Paranthropus boisei is a hominin taxon ers can trace the evolution of metric and nonmetric var- with a distinctive cranial and dental morphology. Its iables across hundreds of thousands of years. This pa- hypodigm has been recovered from sites with good per is a detailed1 review of half a century’s worth of fos- stratigraphic and chronological control, and for some sil evidence and analysis of P. boi se i and traces how morphological regions, such as the mandible and the both its evolutionary history and our understanding of mandibular dentition, the samples are not only rela- its evolutionary history have evolved during the past tively well dated, but they are, by paleontological 50 years. -

Using Sub-Species Level Phylogenies

1 Reconstructing the ancestral phenotypes of great apes and 2 humans (Homininae) using sub-species level phylogenies 3 Keaghan Yaxley1 and Robert Foley2 4 1Leverhulme Centre for Human Evolutionary Studies, University of Cambridge, UK 5 2Leverhulme Centre for Human Evolutionary Studies, University of Cambridge, UK 6 7 8 1 9 Abstract 10 By their close affinity, the African great apes are of interest to the study of human evolution. 11 While numerous researchers have described the ancestors we share with these species with 12 reference to extant great apes, few have done so with phylogenetic comparative methods. 13 One obstacle to the application of these techniques is the within-species phenotypic variation 14 found in this group. Here we leverage this variation, modelling common ancestors using 15 Ancestral State Reconstructions (ASRs) with reference to subspecies level trait data. A 16 subspecies level phylogeny of the African great apes and humans was estimated from full- 17 genome mtDNA sequences and used to implement ASRs for fifteen continuous traits known 18 to vary between great ape subspecies. While including within-species phenotypic variation 19 increased phylogenetic signal for our traits and improved the performance of our ASRs, 20 whether this was done through the inclusion of subspecies phylogeny or through the use of 21 existing methods made little difference. Our ASRs corroborate previous findings that the Last 22 Common Ancestor (LCA) of humans, chimpanzees and bonobos was a chimp-like animal, 23 but also suggest that the LCA of humans, chimpanzees, bonobos and gorillas was an animal 24 unlike any extant African great ape. -

New Fossil Discovery Illuminates the Lives of the Earliest Primates 24 February 2021

New fossil discovery illuminates the lives of the earliest primates 24 February 2021 Royal Society Open Science. "This discovery is exciting because it represents the oldest dated occurrence of archaic primates in the fossil record," Chester said. "It adds to our understanding of how the earliest primates separated themselves from their competitors following the demise of the dinosaurs." Chester and Gregory Wilson Mantilla, Burke Museum Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology and University of Washington biology professor, were co-leads on this study, where the team analyzed fossilized teeth found in the Hell Creek area of northeastern Montana. The fossils, now part of the collections at the University of California Museum of Paleontology, Berkeley, are estimated to be 65.9 Shortly after the extinction of the dinosaurs, the earliest million years old, about 105,000 to 139,000 years known archaic primates, such as the newly described after the mass extinction event. species Purgatorius mckeeveri shown in the foreground, quickly set themselves apart from their competition -- like Based on the age of the fossils, the team estimates the archaic ungulate mammal on the forest floor -- by that the ancestor of all primates (the group specializing in an omnivorous diet including fruit found including plesiadapiforms and today's primates up in the trees. Credit: Andrey Atuchin such as lemurs, monkeys, and apes) likely emerged by the Late Cretaceous—and lived alongside large dinosaurs. Stephen Chester, an assistant professor of anthropology and paleontologist at the Graduate Center, CUNY and Brooklyn College, was part of a team of 10 researchers from across the United States who analyzed several fossils of Purgatorius, the oldest genus in a group of the earliest-known primates called plesiadapiforms. -

Evolution of Grasping Among Anthropoids

doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01582.x Evolution of grasping among anthropoids E. POUYDEBAT,* M. LAURIN, P. GORCE* & V. BELSà *Handibio, Universite´ du Sud Toulon-Var, La Garde, France Comparative Osteohistology, UMR CNRS 7179, Universite´ Pierre et Marie Curie (Paris 6), Paris, France àUMR 7179, MNHN, Paris, France Keywords: Abstract behaviour; The prevailing hypothesis about grasping in primates stipulates an evolution grasping; from power towards precision grips in hominids. The evolution of grasping is hominids; far more complex, as shown by analysis of new morphometric and behavio- palaeobiology; ural data. The latter concern the modes of food grasping in 11 species (one phylogeny; platyrrhine, nine catarrhines and humans). We show that precision grip and precision grip; thumb-lateral behaviours are linked to carpus and thumb length, whereas primates; power grasping is linked to second and third digit length. No phylogenetic variance partitioning with PVR. signal was found in the behavioural characters when using squared-change parsimony and phylogenetic eigenvector regression, but such a signal was found in morphometric characters. Our findings shed new light on previously proposed models of the evolution of grasping. Inference models suggest that Australopithecus, Oreopithecus and Proconsul used a precision grip. very old behaviour, as it occurs in anurans, crocodilians, Introduction squamates and several therian mammals (Gray, 1997; Grasping behaviour is a key activity in primates to obtain Iwaniuk & Whishaw, 2000). On the contrary, the food. The hand is used in numerous activities of manip- precision grip, in which an object is held between the ulation and locomotion and is linked to several func- distal surfaces of the thumb and the index finger, is tional adaptations (Godinot & Beard, 1993; Begun et al., usually viewed as a derived function, linked to tool use 1997; Godinot et al., 1997). -

Phylogenomic Evidence of Adaptive Evolution in the Ancestry of Humans

Phylogenomic evidence of adaptive evolution in the ancestry of humans Morris Goodmana,b,1 and Kirstin N. Sternera aCenter for Molecular Medicine and Genetics and bDepartment of Anatomy and Cell Biology, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, MI 48201 In Charles Darwin’s tree model for life’s evolution, natural selection nomic studies of human evolution. We then highlight the concepts adaptively modifies newly arisen species as they branch apart from that motivate our own efforts and discuss how phylogenomic evi- their common ancestor. In accord with this Darwinian concept, the dence has enhanced our understanding of adaptive evolution in the phylogenomic approach to elucidating adaptive evolution in genes ancestry of modern humans. and genomes in the ancestry of modern humans requires a well supported and well sampled phylogeny that accurately places Darwin’s Views humans and other primates and mammals with respect to one In The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (5), Charles another. For more than a century, first from the comparative immu- Darwin suggested that Africa was the birthplace for humankind. nological work of Nuttall on blood sera and now from comparative The following five passages encapsulate for us Darwin’s thinking genomic studies, molecular findings have demonstrated the close about the place of humans in primate phylogeny and about the kinship of humans to chimpanzees. The close genetic correspond- uniqueness of modern humans. ence of chimpanzees to humans and the relative shortness of our evolutionary separation suggest that most distinctive features of If the anthropomorphous apes be admitted to form a natural subgroup, then as man agrees with them, not only in all those the modern human phenotype had already evolved during our characters which he possesses in common with the whole Cata- ancestry with chimpanzees. -

Jane Goodall: a Timeline 3

Discussion Guide Table of Contents The Life of Jane Goodall: A Timeline 3 Growing Up: Jane Goodall’s Mission Starts Early 5 Louis Leakey and the ‘Trimates’ 7 Getting Started at Gombe 9 The Gombe Community 10 A Family of Her Own 12 A Lifelong Mission 14 Women in the Biological Sciences Today 17 Jane Goodall, in Her Own Words 18 Additional Resources for Further Study 19 © 2017 NGC Network US, LLC and NGC Network International, LLC. All rights reserved. 2 Journeys in Film : JANE The Life of Jane Goodall: A Timeline April 3, 1934 Valerie Jane Morris-Goodall is born in London, England. 1952 Jane graduates from secondary school, attends secretarial school, and gets a job at Oxford University. 1957 At the invitation of a school friend, Jane sails to Kenya, meets Dr. Louis Leakey, and takes a job as his secretary. 1960 Jane begins her observations of the chimpanzees at what was then Gombe Stream Game Reserve, taking careful notes. Her mother is her companion from July to November. 1961 The chimpanzee Jane has named David Greybeard accepts her, leading to her acceptance by the other chimpanzees. 1962 Jane goes to Cambridge University to pursue a doctorate, despite not having any undergraduate college degree. After the first term, she returns to Africa to continue her study of the chimpanzees. She continues to travel back and forth between Cambridge and Gombe for several years. Baron Hugo van Lawick, a photographer for National Geographic, begins taking photos and films at Gombe. 1964 Jane and Hugo marry in England and return to Gombe.