Acknowledgments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 1992

VOLUME 16, NUMBER 12 MASTERS OF THE FEATURES FREE UNIVERSE NICKO Avant-garde drummers Ed Blackwell, Rashied Ali, Andrew JEFF PORCARO: McBRAIN Cyrille, and Milford Graves have secured a place in music history A SPECIAL TRIBUTE Iron Maiden's Nicko McBrain may by stretching the accepted role of When so respected and admired be cited as an early influence by drums and rhythm. Yet amongst a player as Jeff Porcaro passes metal drummers all over, but that the chaos, there's always been away prematurely, the doesn't mean he isn't as vital a play- great discipline and thought. music—and our lives—are never er as ever. In this exclusive interview, Learn how these free the same. In this tribute, friends find out how Nicko's drumming masters and admirers share their fond gears move, and what's tore down the walls. memories of Jeff, and up with Maiden's power- • by Bill Milkowski 32 remind us of his deep ful new album and tour. 28 contributions to our • by Teri Saccone art. 22 • by Robyn Flans THE PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY For thirty years the Percussive Arts Society has fostered credibility, exposure, and the exchange of ideas for percus- sionists of every stripe. In this special report, learn where the PAS has been, where it is, and where it's going. • by Rick Mattingly 36 MD TRIVIA CONTEST Win a Sonor Force 1000 drumkit—plus other great Sonor prizes! 68 COVER PHOTO BY MICHAEL BLOOM Education 58 ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC Back To The Dregs BY ROD MORGENSTEIN Equipment Departments 66 BASICS 42 PRODUCT The Teacher Fallacy News BY FRANK MAY CLOSE-UP 4 EDITOR'S New Sabian Products OVERVIEW BY RICK VAN HORN, 8 UPDATE 68 CONCEPTS ADAM BUDOFSKY, AND RICK MATTINGLY Tommy Campbell, Footwork: 6 READERS' Joel Maitoza of 24-7 Spyz, A Balancing Act 45 Yamaha Snare Drums Gary Husband, and the BY ANDREW BY RICK MATTINGLY PLATFORM Moody Blues' Gordon KOLLMORGEN Marshall, plus News 47 Cappella 12 ASK A PRO 90 TEACHERS' Celebrity Sticks BY ADAM BUDOFSKY 146 INDUSTRY FORUM AND WILLIAM F. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1990

National Endowment For The Arts Annual Report National Endowment For The Arts 1990 Annual Report National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1990. Respectfully, Jc Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. April 1991 CONTENTS Chairman’s Statement ............................................................5 The Agency and its Functions .............................................29 . The National Council on the Arts ........................................30 Programs Dance ........................................................................................ 32 Design Arts .............................................................................. 53 Expansion Arts .....................................................................66 ... Folk Arts .................................................................................. 92 Inter-Arts ..................................................................................103. Literature ..............................................................................121 .... Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ..................................137 .. Museum ................................................................................155 .... Music ....................................................................................186 .... 236 ~O~eera-Musicalater ................................................................................ -

Robert Glasper's In

’s ION T T R ESSION ER CLASS S T RO Wynton Marsalis Wayne Wallace Kirk Garrison TRANSCRIP MAS P Brass School » Orbert Davis’ Mission David Hazeltine BLINDFOLD TES » » T GLASPE R JAZZ WAKE-UP CALL JAZZ WAKE-UP ROBE SLAP £3.50 £3.50 U.K. T.COM A Wes Montgomery Christian McBride Wadada Leo Smith Wadada Montgomery Wes Christian McBride DOWNBE APRIL 2012 DOWNBEAT ROBERT GLASPER // WES MONTGOMERY // WADADA LEO SmITH // OrbERT DAVIS // BRASS SCHOOL APRIL 2012 APRIL 2012 VOLume 79 – NumbeR 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Managing Editor Bobby Reed News Editor Hilary Brown Reviews Editor Aaron Cohen Contributing Editors Ed Enright Zach Phillips Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Assistant Theresa Hill 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Or- leans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

Vision Festival 21 Brochure

THE CREATIVE OPTION TOGETHER WE CONTINUE TO MAKE VISIONS REAL Our goal is to keep alive, in hearts and minds, the idealism, integrity and sense of responsibility that has inspired generations. We support the Present by remembering & respecting the Past & Prepare a Future where Improvisation and Freedom have a place. THIS IS ONLY POSSIBLE WITH YOUR HELP Charlotte Ka, ‘Dance a Celebration of Life’ Arts for Art presents Free Jazz as a sacred art-form, based in the Ideals of Freedom, Artist Info Page 24 Marcy Rosenblat, ‘Reveal’ Justice and Excellence. The art expresses our sense of hope and belief in the possibility of freedom, A Freedom to be our most unique self. So we push ourselves to do more, to redefine our self, our art and our communities. The music was built by self-determination. Where the artist defines, presents their work, not waiting for permission. Hope, Freedom, Self-determination are powerful ideas in any time, and particularly in this time. VISUAL ART AT VISION 21 AT ART VISUAL What we do or don’t do – does matter. We make a difference in our world and in our Lives by supporting what feeds our Souls. Bill Mazza, If the Vision Festival and the Work of Arts for Art feeds Souls then you should support it. ‘Vision 20, Day 5, Set 3, Wadada Leo Smith/Aruan Ortiz Duo’’ Our Humanity and Creativity needs a community of supporters who share our ideals. Jonas Hidalgo ENSURE ARTS FOR ART’S FUTURE ■ BE A MEMBER / DONATE TO ARTS FOR ART ■ BECOME ACTIVE IN THE AFA COMMUNITY Visit: www.artsforart.org/support or stop by the Arts for Art table at the Vision Festival. -

Too Many Notes: Complexity and Culture in Voyager����� Lewis, George E

Too Many Notes: Complexity and Culture in Voyager Lewis, George E. Leonardo Music Journal, Volume 10, 2000, pp. 33-39 (Article) Published by The MIT Press For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/lmj/summary/v010/10.1lewis.html Access Provided by University of California @ Santa Cruz at 09/27/11 9:42PM GMT W A Y S WAYS & MEANS & M E A Too Many Notes: Computers, N S Complexity and Culture in Voyager ABSTRACT The author discusses his computer music composition, Voyager, which employs a com- George E. Lewis puter-driven, interactive “virtual improvising orchestra” that ana- lyzes an improvisor’s performance in real time, generating both com- plex responses to the musician’s playing and independent behavior arising from the program’s own in- oyager [1,2] is a nonhierarchical, interactive mu- pears to stand practically alone in ternal processes. The author con- V the trenchancy and thoroughness tends that notions about the na- sical environment that privileges improvisation. In Voyager, improvisors engage in dialogue with a computer-driven, inter- of its analysis of these issues with ture and function of music are active “virtual improvising orchestra.” A computer program respect to computer music. This embedded in the structure of soft- ware-based music systems and analyzes aspects of a human improvisor’s performance in real viewpoint contrasts markedly that interactions with these sys- time, using that analysis to guide an automatic composition with Catherine M. Cameron’s [7] tems tend to reveal characteris- (or, if you will, improvisation) program that generates both rather celebratory ethnography- tics of the community of thought complex responses to the musician’s playing and indepen- at-a-distance of what she terms and culture that produced them. -

Ecuador and Peru

Grab your passport and join ArtStart artists on an unforgettable adventure to Ecuador and Peru through the arts! The astounding diversity and rich heritage of these two countries provide a wonderful springboard for art inspired by traditional art forms—from music to dance to storytelling and visual arts. Classes for pre-school, school-age, and teens. PASSPORT TO Ecuador and Peru THROUGH THE ARTS Ecuador JULY 6-10, 2020 Journey to Ecuador, a country straddling the equator on South America’s west coast. Its diverse landscape encompasses Amazon jungle, Andean highlands and the wildlife-rich Galápagos Islands. You learn about the three distinct ecosystems and the wildlife that inhabit them. In the afternoon you shift your emphasis from nature to learn about community life and how customs and traditions of the ancient Incas, the indigenous people of Ecuador, live on through art, music and dance. Peru JULY 13-17, 2020 Head south to Peru, a country that borders Ecuador. Here you visit the Andes, one of the highest mountain ranges in the world running the length of Peru. The valleys and mountains for the Andes are home to the ancient culture of the Incas and their modern day relatives, the Quechua, or “the people”. Working with artists, you learn about the Inca way of life and how the Spanish influenced the art and culture of the indigenous people of Peru. Each day you create art work inspired by the land and animals, the people and culture. BOOK YOUR ARTS EXCURSION TO ECUADOR & PERU NOW! WEEK ONE JULY 6-10, 2020 The Ecology of Ecuador MORNING CLASSES 8:30 -11:45 AM 401 Drawing and Painting Wildlife of the Galapagos Islands Ecuador is the first country in the world to adopt the Rights of Nature as part of its Constitution. -

The Avant-Garde in Jazz As Representative of Late 20Th Century American Art Music

THE AVANT-GARDE IN JAZZ AS REPRESENTATIVE OF LATE 20TH CENTURY AMERICAN ART MUSIC By LONGINEU PARSONS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2017 © 2017 Longineu Parsons To all of these great musicians who opened artistic doors for us to walk through, enjoy and spread peace to the planet. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my professors at the University of Florida for their help and encouragement in this endeavor. An extra special thanks to my mentor through this process, Dr. Paul Richards, whose forward-thinking approach to music made this possible. Dr. James P. Sain introduced me to new ways to think about composition; Scott Wilson showed me other ways of understanding jazz pedagogy. I also thank my colleagues at Florida A&M University for their encouragement and support of this endeavor, especially Dr. Kawachi Clemons and Professor Lindsey Sarjeant. I am fortunate to be able to call you friends. I also acknowledge my friends, relatives and business partners who helped convince me that I wasn’t insane for going back to school at my age. Above all, I thank my wife Joanna for her unwavering support throughout this process. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 4 LIST OF EXAMPLES ...................................................................................................... 7 ABSTRACT -

Chicago Tribune

Colsons return to Chicago with new sounds Adegoke Steve Colson and Iqua Colson bring their experimental music to Constellation on Saturday, Aug. 12, 2017. (Mikel Colson photo) By Howard Reich Chicago Tribune AUGUST 9, 2017, 9:25 AM early 50 years ago, a promising young pianist from New Jersey began studying music at N Northwestern University — and discovered sounds he’d never encountered before. Not so much at school, where classical music predominated, but elsewhere in Evanston and Chicago, where musical revolutions were underway. For just two years before Adegoke Steve Colson came here in 1967, a contingent of fearlessly innovative South Side artists had formed the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), a collective that was inventing radical new techniques, concepts and practices for composing and improvising music. Even closer to campus, saxophonist Fred Anderson was making his Birdhouse venue in Evanston a nexus for new music and became an early mentor to Colson. The creative ferment of that period transformed Colson, who will return to Chicago to co-lead a quintet with vocalist Iqua Colson, his wife, Saturday night at Constellation. As he prepares for this engagement, memories of those early days come flooding back. “I remember I saw a flyer for Fred Anderson, because he lived there in Evanston … and we could go by and join his band,” says pianist Colson, who often sat in with the singular improviser. “When I started playing with guys in the AACM. Sometimes (bassist) Fred Hopkins would show up, (drummer) Steve McCall would show up,” adds Colson, who formed a jazz band with fellow student Chico Freeman. -

Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21St Century Chicago

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 Sacred Freedom: Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21St Century Chicago Adam Zanolini The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1617 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SACRED FREEDOM: SUSTAINING AFROCENTRIC SPIRITUAL JAZZ IN 21ST CENTURY CHICAGO by ADAM ZANOLINI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 ADAM ZANOLINI All Rights Reserved ii Sacred Freedom: Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21st Century Chicago by Adam Zanolini This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _________________ __________________________________________ DATE David Grubbs Chair of Examining Committee _________________ __________________________________________ DATE Norman Carey Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: _________________ __________________________________________ DATE Jeffrey Taylor _________________ __________________________________________ DATE Fred Moten _________________ __________________________________________ DATE Michele Wallace iii ABSTRACT Sacred Freedom: Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21st Century Chicago by Adam Zanolini Advisor: Jeffrey Taylor This dissertation explores the historical and ideological headwaters of a certain form of Great Black Music that I call Afrocentric spiritual jazz in Chicago. However, that label is quickly expended as the work begins by examining the resistance of these Black musicians to any label. -

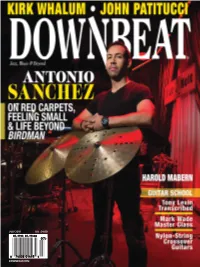

Downbeat.Com July 2015 U.K. £4.00

JULY 2015 2015 JULY U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT ANTONIO SANCHEZ • KIRK WHALUM • JOHN PATITUCCI • HAROLD MABERN JULY 2015 JULY 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 7 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, -

Myra Melford Trio Alive in the House of Saints Part 2 Myra Melford Is a Polystylist, Who Draws on and Creates for Some Writers, Even in the Most Illustrious

Myra Melford Trio Alive In The House Of Saints Part 2 Myra Melford is a polystylist, who draws on and creates For some writers, even in the most illustrious 7 multiple playing styles. She combines free cases, a signature style is a branding device. Art historian 1 0 playing with strong melodic content and Christopher Atkins’s recent book The Signature Style of Frans 2 , driving rhythms, from a wide range of influ - Hals illuminates the relation of subjectivity and style, interpret - 4 1 ences. In Alive In The House Of Saints ing the Dutch master’s style as a personal and workshop brand. r e b these include stomping classic jazz piano, Initially, Hals worked in two distinct modes – smooth for por - o t the funky attack of Horace Silver, gospel traiture, rough and unblended for genre scenes. In the 1630s c O plangency, Keith Jarrett’s country and he abandoned genre painting, and began to develop a sketchy , n e blues lyricism, and Don Pullen-style free aesthetic for portraits. Scientific examination shows that Hals o t l i jazz. Though from quite early in her career, worked up his paintings over several sessions, while seeming - h m a Alive is one of her finest recordings – high ly persuading viewers that his sketches were spontaneous. H s on the musical power spectrum, one of the It’s not necessary to be a connoisseur, in order y T d n most exciting albums of piano jazz. to tell a Hals from a Rembrandt or a Vermeer. Hals, it seems, t A Her polystylism contrasts developed a sketchy manner – increasing the roughness and n with artists who have a strong signature looseness of individual strokes, and the degree to which they n i I style – an approach that allows listeners to were unblended – in order to emphasise an individual style. -

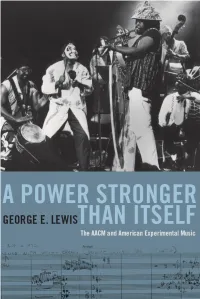

A Power Stronger Than Itself

A POWER STRONGER THAN ITSELF A POWER STRONGER GEORGE E. LEWIS THAN ITSELF The AACM and American Experimental Music The University of Chicago Press : : Chicago and London GEORGE E. LEWIS is the Edwin H. Case Professor of American Music at Columbia University. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2008 by George E. Lewis All rights reserved. Published 2008 Printed in the United States of America 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-47695-7 (cloth) ISBN-10: 0-226-47695-2 (cloth) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lewis, George, 1952– A power stronger than itself : the AACM and American experimental music / George E. Lewis. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ), discography (p. ), and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-226-47695-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-226-47695-2 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians—History. 2. African American jazz musicians—Illinois—Chicago. 3. Avant-garde (Music) —United States— History—20th century. 4. Jazz—History and criticism. I. Title. ML3508.8.C5L48 2007 781.6506Ј077311—dc22 2007044600 o The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992. contents Preface: The AACM and American Experimentalism ix Acknowledgments xv Introduction: An AACM Book: Origins, Antecedents, Objectives, Methods xxiii Chapter Summaries xxxv 1 FOUNDATIONS AND PREHISTORY