I Believe in My System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AC;T I - SCENE 1 No.1 Overture Seep

7 AC;T I - SCENE 1 No.1 Overture Seep. 85 IOrchestra) Music seg11es as one. No. 2 Sweet And Lowdown 5-.:e p. 85 (Jimmy, Jeannie, Cirls & Cuys) Lights Up: A speakeasy in New York Cih;. JEANNIE leads a gaggle of CHORUS GIRLS. The surrounding tables are full of handsome YOUNG MEN. We are at a society bachelor party - rich boys having fun. JEANNIE & GIRLS. Grab a cab and go down To where the band is playing; Where milk and honey flow down Where ev'ry one is saying "Blow that sweet and low-down!" Busy as a beaver, You'll dance until you totter; You're sure to get the fever For nothing could be hotter Oh, that sweet and low-down! JEANNIE. (Over music) All right, peoples, peoples - listen up! Now this is a very sad occasion, 'cause tomorrow morning, our own Jimmy Winter is gettin' married for the third time! JIMMY. (Stands up) Fourth time! EVERYBODY cheers. JlMMY. (Continued) But this time, I'm not marrying some cheap chorus girl! JEANNIE & GIRLS. Awww. JIMMY. Sorry, cheap chorus girls. EVERYBODY cheers. JIMMY. (sung) There's a cabaret in this city I can recommend to you; Peps you up like electricity When the band is blowing blue. \:IC - l'rompt Book 8 .. I (JJ MY. They play nothing classic, Oh no• Down there, They crave nothing e se Bu he low-down there I you need a on·c nd he need is chron c If you're in a crisis. my advice is }EA lE & L Grab a cab and go down Grab a cab and go down To where the band 1s playin : Where he band i playing; Where milk and honey flow down Where ev'ry one is sayin' E IR Blow Blow that eet and low-d wnl" Low low down t Busy as a beaver, Busy as a beaver. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

Doing Sound Slaten Dissertation Deposit

Doing Sound: An Ethnography of Fidelity, Temporality and Labor Among Live Sound Engineers Whitney Slaten Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Whitney Slaten All rights reserved ABSTRACT Doing Sound: An Ethnography of Fidelity, Temporality and Labor Among Live Sound Engineers Whitney Slaten This dissertation ethnographically represents the work of three live sound engineers and the profession of live sound reinforcement engineering in the New York City metropolitan area. In addition to amplifying music to intelligible sound levels, these engineers also amplify music in ways that engage the sonic norms associated with the pertinent musical genres of jazz, rock and music theater. These sonic norms often overdetermine audience members' expectations for sound quality at concerts. In particular, these engineers also work to sonically and visually mask themselves and their equipment. Engineers use the term “transparency” to describe this mode of labor and the relative success of sound reproduction technologies. As a concept within the realm of sound reproduction technologies, transparency describes methods of reproducing sounds without coloring or obscuring the original quality. Transparency closely relates to “fidelity,” a concept that became prominent throughout the late nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries to describe the success of sound reproduction equipment in making the quality of reproduced sound faithful to its original. The ethnography opens by framing the creative labor of live sound engineering through a process of “fidelity.” I argue that fidelity dynamically oscillates as struggle and satisfaction in live sound engineers’ theory of labor and resonates with their phenomenological encounters with sounds and social positions as laborers at concerts. -

085765096700 Hd Movies / Game / Software / Operating System

085765096700 --> SMS / CHAT ON / WHATSAPP / LINE HD MOVIES / GAME / SOFTWARE / OPERATING SYSTEM / EBOOK VIDEO TUTORIAL / ANIME / TV SERIAL / DORAMA / HD DOKUMENTER / VIDEO CONCERT Pertama-tama saya ucapkan terimaksih agan2 yang telah mendownload list ini.. Harap di isi dan kirim ke [email protected] Isi data : NAMA : ALAMAT : NO HP : HARDISK : TOTAL KESELURUHAN PENGISIAN HARDISK : Untuk pengisian hardisk: 1. Tinggal titipkan hardisk internal/eksternal kerumah saya dari jam 07:00-23:00 WIB untuk alamat akan saya sms.. 2. List pemesanannya di kirim ke email [email protected]/saat pengantar hardisknya jg boleh, bebas pilih yang ada di list.. 3. Pembayaran dilakukan saat penjemputan hardisk.. 4. Terima pengiriman hardisk, bagi yang mengirimkan hardisknya internal dan external harap memperhatikan packingnya.. Untuk pengisian beserta hardisknya: 1. Transfer rekening mandiri, setelah mendapat konfirmasi transfer, pesanan baru di proses.. 2. Hardisk yang telah di order tidak bisa di batalkan.. 3. Pengiriman menggunakan jasa Jne.. 4. No resi pengiriman akan di sms.. Lama pengerjaan 1 - 4 hari tergantung besarnya isian dan antrian tapi saya usahakan secepatnya.. Harga Pengisian Hardisk : Dibawah Hdd320 gb = 50.000 Hdd 500 gb = 70.000 Hdd 1 TB =100.000 Hdd 1,5 TB = 135.000 Hdd 2 TB = 170.000 Yang memakai hdd eksternal usb 2.0 kena biaya tambahan Check ongkos kirim http://www.jne.co.id/ BATAM GAME 085765096700 --> SMS / CHAT ON / WHATSAPP / LINE HD MOVIES / GAME / SOFTWARE / OPERATING SYSTEM / EBOOK VIDEO TUTORIAL / ANIME / TV SERIAL / DORAMA / HD DOKUMENTER / VIDEO CONCERT Pertama-tama saya ucapkan terimaksih agan2 yang telah mendownload list ini.. Movies 0 GB Game Pc 0 GB Software 0 GB EbookS 0 GB Anime dan Concert 0 GB 3D / TV SERIES / HD DOKUMENTER 0 GB TOTAL KESELURUHAN 0 GB 1. -

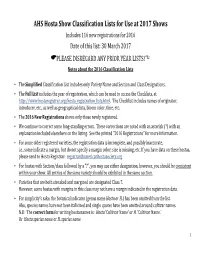

AHS Hosta Show Classification Lists for Use at 2017 Shows

AHS Hosta Show Classification Lists for Use at 2017 Shows Includes 116 new registrations for 2016 Date of this list: 30 March 2017 FPLEASE DISREGARD ANY PRIOR YEAR LISTS! Notes about the 2016 Classification Lists • The Simplified Classification List includes only Variety Name and Section and Class Designations. • The Full List includes the year of registration, which can be used to access the Checklists, at http://www.hostaregistrar.org/hosta_registration_lists.html . The Checklist includes names of originator, introducer, etc., as well as geographical data, bloom color, time, etc. • The 2016 New Registrations shows only those newly registered. • We continue to correct some long-standing errors. These corrections are noted with an asterisk (*) with an explanation included elsewhere on the listing. See the printed “2016 Registrations” for more information. • For some older registered varieties, the registration data is incomplete, and possibly inaccurate, i.e., some indicate a margin, but do not specify a margin color; size is missing, etc. If you have data on these hostas, please send to Hosta Registrar: [email protected] • For hostas with Section/class followed by a “?”, you may use either designation, however, you should be consistent within your show. All entries of the same variety should be exhibited in the same section. • Varieties that are both streaked and margined are designated Class 7. However, some hostas with margins in this class may not have a margin indicated in the registration data. • For simplicity’s sake, the botanical indicator (genus name Hosta or H .) has been omitted from the list. Also, species names have not been italicized and single quotes have been omitted around cultivar names. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

Table of Contents

1 •••I I Table of Contents Freebies! 3 Rock 55 New Spring Titles 3 R&B it Rap * Dance 59 Women's Spirituality * New Age 12 Gospel 60 Recovery 24 Blues 61 Women's Music *• Feminist Music 25 Jazz 62 Comedy 37 Classical 63 Ladyslipper Top 40 37 Spoken 65 African 38 Babyslipper Catalog 66 Arabic * Middle Eastern 39 "Mehn's Music' 70 Asian 39 Videos 72 Celtic * British Isles 40 Kids'Videos 76 European 43 Songbooks, Posters 77 Latin American _ 43 Jewelry, Books 78 Native American 44 Cards, T-Shirts 80 Jewish 46 Ordering Information 84 Reggae 47 Donor Discount Club 84 Country 48 Order Blank 85 Folk * Traditional 49 Artist Index 86 Art exhibit at Horace Williams House spurs bride to change reception plans By Jennifer Brett FROM OUR "CONTROVERSIAL- SUffWriter COVER ARTIST, When Julie Wyne became engaged, she and her fiance planned to hold (heir SUDIE RAKUSIN wedding reception at the historic Horace Williams House on Rosemary Street. The Sabbats Series Notecards sOk But a controversial art exhibit dis A spectacular set of 8 color notecards^^ played in the house prompted Wyne to reproductions of original oil paintings by Sudie change her plans and move the Feb. IS Rakusin. Each personifies one Sabbat and holds the reception to the Siena Hotel. symbols, phase of the moon, the feeling of the season, The exhibit, by Hillsborough artist what is growing and being harvested...against a Sudie Rakusin, includes paintings of background color of the corresponding chakra. The 8 scantily clad and bare-breasted women. Sabbats are Winter Solstice, Candelmas, Spring "I have no problem with the gallery Equinox, Beltane/May Eve, Summer Solstice, showing the paintings," Wyne told The Lammas, Autumn Equinox, and Hallomas. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home -

Intertwined Cultural Journeys: an Autoethnography of Learning, Teaching, and Affirming Diversity Through Multicultural Music

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Fall 2011 Intertwined Cultural Journeys: An Autoethnography of Learning, Teaching, and Affirming Diversity through Multicultural Music Kathryn Blackmon Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Recommended Citation Blackmon, Kathryn, "Intertwined Cultural Journeys: An Autoethnography of Learning, Teaching, and Affirming Diversity through Multicultural Music" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 559. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/559 This dissertation (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTERTWINED CULTURAL JOURNEYS: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHY OF LEARNING, TEACHING, AND AFFIRMING DIVERSITY THROUGH MULTICULTURAL MUSIC by KATHRYN BLACKMON (Under the Direction of Sabrina N. Ross) ABSTRACT As our schools gain more and more children from different cultures and ethnicities, there is an increasing need to diversify curriculum to assist in cultivating tolerance and understanding. Drawing upon an eclectic group of theorists who highlight the importance of meaningful curricula and education, and using autoethnography as method, I -

Titres Attribués Titles Awarded | Titres Attribués January/Janvierjune/Juin 2015 1 – 31

Titles awarded x Titres attribués Titles awarded | Titres attribués January/janvierJune/juin 2015 1 – 31 CHAMPION Ch Clitheroe Once In A Blue Moon (ZN477054) 21 Jun 2015 (Ch Sonshine Over Clitheroe CD WC JH Cgn Rae2 ex Ch Clitheroe’s Raggedy Ann) June 01 - June 30, 2015 Ch Donieka’s Party Time (AS528727) 16 Jun 2015 group one | groupe un (Goldtales Mister Big Time Ra ex Ch Donieka’s Christmas Wish) Ch Emery’s Gumbo Ya Ya (1127667) 19 Jun 2015 BARBET (Ch Sweetgold Mr. Wonderful ex Emery’s Talk That Talk) Ch Goldiva’s Love N The Adirondaks (ERN15000508) 20 Jun 2015 Ch Hickorytavern Secret Entourage (BG576905) 27 Jun 2015 (Goldiva’s Dancin’n The Moonlight ex Church’s Legacy Autumn Breeze) (Gch Neigenuveaux’s Gambit CD Cgn Re ex Ch Hickorytavern Intl Intrigue) Ch Goldiva’s Up With A Twist (ERN15000510) 26 Jun 2015 Ch Yara Biscay’s for Butterblac (BL567057) 07 Jun 2015 (Nautilus Goldiva’s Good N Plenty ex Goldiva’s Pink Martini) (Ursus Di Barbochos Reiau de Prouvenco ex Ch Vegas Biscay’s for Butterblac Cgn) Ch Goldiva’s Wild Blue Yonder (ERN15000511) 13 Jun 2015 IRISH RED & WHITE SETTER (Golden Trip Magic Carpet at Nautilus ex Goldiva’s Midsummer Night’s Folly) Ch Aislingcudo Is Caiseal Na Ri (AW537882) 05 Jun 2015 Ch Goldnote’s MacIntyre of Argyle (BG572403) 28 Jun 2015 (Ch Shireoak Iced Flame ex Ch Aisling Cudo Is Niamh OisÕn) (Ch Kyon’s Rolling Stone ex Ch Goldnote’s a Pip From a Pipit Rn) Ch Clancuddy’s Seize The Day Cgn (AL518085) 06 Jun 2015 Ch Goldstreak The Favorite List (BC554612) 19 Jun 2015 (Ch Clancuddy Legolas of Mirkwood ex Ch -

Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 3-2-2017 On My Grind: Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy Evan Nave Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Creative Writing Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Educational Methods Commons Recommended Citation Nave, Evan, "On My Grind: Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 697. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/697 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON MY GRIND: FREESTYLE RAP PRACTICES IN EXPERIMENTAL CREATIVE WRITING AND COMPOSITION PEDAGOGY Evan Nave 312 Pages My work is always necessarily two-headed. Double-voiced. Call-and-response at once. Paranoid self-talk as dichotomous monologue to move the crowd. Part of this has to do with the deep cuts and scratches in my mind. Recorded and remixed across DNA double helixes. Structurally split. Generationally divided. A style and family history built on breaking down. Evidence of how ill I am. And then there’s the matter of skin. The material concerns of cultural cross-fertilization. Itching to plant seeds where the grass is always greener. Color collaborations and appropriations. Writing white/out with black art ink. Distinctions dangerously hidden behind backbeats or shamelessly displayed front and center for familiar-feeling consumption. -

1 Below Is a Comprehensive List of All the Lines Hello Barbie Says As O

Below is a comprehensive list of all the lines Hello Barbie says as of November 17, 2015. We are consistently updating and enhancing the product’s vocabulary and will update the lines on this site periodically to reflect any changes. OK, sooooo..... I love hanging out with you! (SIGH) Wow... there's so much we can talk about... I've got a question for you... Oh! I know what we can talk about... Oh, I know what we can do now... Speaking of things you want to be when you grow up... You know what I want to talk about? FRIENDS! So, let's talk friends! Ooh, why don't we talk about friends! Hey... let's talk about friends for a bit! I'm the most myself when I'm around my friends, just playing games and imagining what we'll be when we grow up! You know, I really appreciate my friends who have a completely unique sense of style... like you! You know, on those days where waking up for school is hard, I just think about how much fun it'll be to see my friends. ©2015 Mattel. All Rights Reserved. Version 2 1 You know, talking about all the fun things we do is making me think about who we could do them with ... friends! So we've been talking about family, let's talk about the other people in our lives that mean a lot to us ...like our friends! I bet someone who's a friend to animals knows a thing or two about being a friend to people.