Fair Use, Girl Talk, and Digital Sampling: an Empirical Study of Music Sampling's Effect on the Market for Copyrighted Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman in Rap Videos: a Content Analysis

The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman in Rap Videos: A Content Analysis Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Manriquez, Candace Lynn Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 03:10:19 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/624121 THE SYMBOLIC ANNIHILATION OF THE BLACK WOMAN IN RAP VIDEOS: A CONTENT ANALYSIS by Candace L. Manriquez ____________________________ Copyright © Candace L. Manriquez 2017 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 Running head: THE SYMBOLIC ANNIHILATION OF THE BLACK WOMAN 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR The thesis titled The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman: A Content Analysis prepared by Candace Manriquez has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for a master’s degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgement of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. -

ENG 350 Summer12

ENG 350: THE HISTORY OF HIP-HOP With your host, Dr. Russell A. Potter, a.k.a. Professa RAp Monday - Thursday, 6:30-8:30, Craig-Lee 252 http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ In its rise to the top of the American popular music scene, Hip-hop has taken on all comers, and issued beatdown after beatdown. Yet how many of its fans today know the origins of the music? Sure, people might have heard something of Afrika Bambaataa or Grandmaster Flash, but how about the Last Poets or Grandmaster CAZ? For this class, we’ve booked a ride on the wayback machine which will take us all the way back to Hip-hop’s precursors, including the Blues, Calypso, Ska, and West African griots. From there, we’ll trace its roots and routes through the ‘parties in the park’ in the late 1970’s, the emergence of political Hip-hop with Public Enemy and KRS-One, the turn towards “gangsta” style in the 1990’s, and on into the current pantheon of rappers. Along the way, we’ll take a closer look at the essential elements of Hip-hop culture, including Breaking (breakdancing), Writing (graffiti), and Rapping, with a special look at the past and future of turntablism and digital sampling. Our two required textbook are Bradley and DuBois’s Anthology of Rap (Yale University Press) and Neal and Forman’s That's the Joint: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader are both available at the RIC campus store. Films shown in part or in whole will include Bamboozled, Style Wars, The Freshest Kids: A History of the B-Boy, Wild Style, and Zebrahead; there will is also a course blog with a discussion board and a wide array of links to audio and text resources at http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ WRITTEN WORK: An informal response to our readings and listenings is due each week on the blog. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Milli-Q Gradient and Milli-Q Gradient A10 User Manual

Milli-Q® Gradient and Milli-Q® Gradient A10® User Manual Notice The information in this document is subject to change without notice and should not be construed as a commitment by Millipore Corporation. Millipore Corporation assumes no responsibility for any errors that might appear in this document. This manual is believed to be complete and accurate at the time of publication. In no event shall Millipore Corporation be liable for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising from the use of this manual. We manufacture and sell water purification systems designed to produce pure or ultrapure water with specific characteristics (μS/cm, T, TOC, CFU/ml, Eu/ml) when it leaves the water purification system provided that the Elix Systems are fed with water quality within specifications, and properly maintained as required by the supplier. We do not warrant these systems for any specific applications. It is up to the end user to determine if the quality of the water produced by our systems matches his expectations, fits with norms/legal requirements and to bear responsibility resulting from the usage of the water. Millipore’s Standard Warranty Millipore Corporation (“Millipore”) warrants its products will meet their applicable published specifications when used in accordance with their applicable instructions for a period of one year from shipment of the products. MILLIPORE MAKES NO OTHER WARRANTY, EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED. THERE IS NO WARRANTY OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. The warranty provided herein and the data, specifications and descriptions of Millipore products appearing in Millipore’s published catalogues and product literature may not be altered except by express written agreement signed by an officer of Millipore. -

Helena Mace Song List 2010S Adam Lambert – Mad World Adele – Don't You Remember Adele – Hiding My Heart Away Adele

Helena Mace Song List 2010s Adam Lambert – Mad World Adele – Don’t You Remember Adele – Hiding My Heart Away Adele – One And Only Adele – Set Fire To The Rain Adele- Skyfall Adele – Someone Like You Birdy – Skinny Love Bradley Cooper and Lady Gaga - Shallow Bruno Mars – Marry You Bruno Mars – Just The Way You Are Caro Emerald – That Man Charlene Soraia – Wherever You Will Go Christina Perri – Jar Of Hearts David Guetta – Titanium - acoustic version The Chicks – Travelling Soldier Emeli Sande – Next To Me Emeli Sande – Read All About It Part 3 Ella Henderson – Ghost Ella Henderson - Yours Gabrielle Aplin – The Power Of Love Idina Menzel - Let It Go Imelda May – Big Bad Handsome Man Imelda May – Tainted Love James Blunt – Goodbye My Lover John Legend – All Of Me Katy Perry – Firework Lady Gaga – Born This Way – acoustic version Lady Gaga – Edge of Glory – acoustic version Lily Allen – Somewhere Only We Know Paloma Faith – Never Tear Us Apart Paloma Faith – Upside Down Pink - Try Rihanna – Only Girl In The World Sam Smith – Stay With Me Sia – California Dreamin’ (Mamas and Papas) 2000s Alicia Keys – Empire State Of Mind Alexandra Burke - Hallelujah Adele – Make You Feel My Love Amy Winehouse – Love Is A Losing Game Amy Winehouse – Valerie Amy Winehouse – Will You Love Me Tomorrow Amy Winehouse – Back To Black Amy Winehouse – You Know I’m No Good Coldplay – Fix You Coldplay - Yellow Daughtry/Gaga – Poker Face Diana Krall – Just The Way You Are Diana Krall – Fly Me To The Moon Diana Krall – Cry Me A River DJ Sammy – Heaven – slow version Duffy -

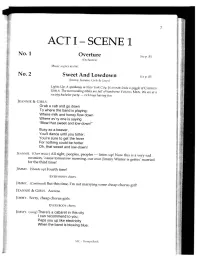

AC;T I - SCENE 1 No.1 Overture Seep

7 AC;T I - SCENE 1 No.1 Overture Seep. 85 IOrchestra) Music seg11es as one. No. 2 Sweet And Lowdown 5-.:e p. 85 (Jimmy, Jeannie, Cirls & Cuys) Lights Up: A speakeasy in New York Cih;. JEANNIE leads a gaggle of CHORUS GIRLS. The surrounding tables are full of handsome YOUNG MEN. We are at a society bachelor party - rich boys having fun. JEANNIE & GIRLS. Grab a cab and go down To where the band is playing; Where milk and honey flow down Where ev'ry one is saying "Blow that sweet and low-down!" Busy as a beaver, You'll dance until you totter; You're sure to get the fever For nothing could be hotter Oh, that sweet and low-down! JEANNIE. (Over music) All right, peoples, peoples - listen up! Now this is a very sad occasion, 'cause tomorrow morning, our own Jimmy Winter is gettin' married for the third time! JIMMY. (Stands up) Fourth time! EVERYBODY cheers. JlMMY. (Continued) But this time, I'm not marrying some cheap chorus girl! JEANNIE & GIRLS. Awww. JIMMY. Sorry, cheap chorus girls. EVERYBODY cheers. JIMMY. (sung) There's a cabaret in this city I can recommend to you; Peps you up like electricity When the band is blowing blue. \:IC - l'rompt Book 8 .. I (JJ MY. They play nothing classic, Oh no• Down there, They crave nothing e se Bu he low-down there I you need a on·c nd he need is chron c If you're in a crisis. my advice is }EA lE & L Grab a cab and go down Grab a cab and go down To where the band 1s playin : Where he band i playing; Where milk and honey flow down Where ev'ry one is sayin' E IR Blow Blow that eet and low-d wnl" Low low down t Busy as a beaver, Busy as a beaver. -

American Express and Jagged Little Pill Present Special Livestream Event You Live, You Learn: a Night with Alanis Morissette and ‘Jagged Little Pill’

NEWS RELEASE American Express and Jagged Little Pill present special livestream event You Live, You Learn: A Night with Alanis Morissette and ‘Jagged Little Pill’ 5/19/2020 Today, American Express and Jagged Little Pill are pleased to present a special Facebook and YouTube livestream benet event, You Live, You Learn: A Night with Alanis Morissette and ‘Jagged Little Pill’ on Tuesday, May 19 at 8:00PM ET in support of the COVID-19 emergency relief eorts of The Actors Fund. The event will bring Cardmembers closer to the theatre experience they love and marks the rst of many virtual entertainment experiences Cardmembers can enjoy in the coming months. "Our Cardmembers’ lives have changed so much over the last few weeks and so have their plans when it comes to entertainment. American Express Experiences continues to be one of the most valuable and unique benets on our Cards and we remain committed to oering our Cardmembers exclusive access to theatre, concert and dining experiences even while at home,” said Megan McKee, Vice President & General Manager, Consumer Card Services, American Express Canada. “We know our Cardmembers are always on the lookout for special entertainment experiences and this livestream event marks a new way that we’ll bring those to life in a completely dierent environment.” The one-hour event features six exclusive performances from the Broadway cast of Jagged Little Pill and seven-time Grammy Award-winning songwriter and recording artist Alanis Morissette, who co-hosts the livestream with SafePlace International founder Justin Hilton. The event also includes conversations with cast members and special appearances by the show’s Oscar-winning writer Diablo Cody (Juno, Tully), Tony-winning director Diane Paulus (Waitress, Pippin), Olivier Award-winning choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui (Beyoncé at The Grammys; The Carters’ “Apesh*t”), and Pulitzer Prize winning orchestrator/arranger Tom Kitt (Next to Normal, American Idiot). -

User Manual Milli-Q Integral 3/5/10/15 Systems

User Manual Milli-Q Integral 3/5/10/15 Systems About this User Manual Purpose x This User Manual is intended for use with a Milli-Q® Integral Water Purification System. x This User Manual is a guide for use during the installation, normal operation and maintenance of a Milli-Q Integral Water Purification System. It is highly recommended to completely read this manual and to fully comprehend its contents before attempting installation, normal operation or maintenance of the Water Purification System. x If this User Manual is not the correct one for your Water Purification System, then please contact Millipore. Terminology The term “Milli-Q Integral Water Purification System” is replaced by the term “Milli-Q System” for the remainder of this User Manual unless otherwise noted. Document Rev. 0, 05/2008 About Millipore Telephone See the business card(s) on the inside cover of the User Manual binder. Internet Site www.millipore.com/bioscience Address Manufacturing Millipore SAS Site 67120 Molsheim FRANCE 2 Legal Information Notice The information in this document is subject to change without notice and should not be construed as a commitment by Millipore Corporation. Millipore Corporation assumes no responsibility for any errors that might appear in this document. This manual is believed to be complete and accurate at the time of publication. In no event shall Millipore Corporation be liable for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising from the use of this manual. We manufacture and sell water purification systems designed to produce pure or ultrapure water with specific characteristics (PS/cm, T, TOC, CFU/ml, Eu/ml) when it leaves the water purification system provided that the System is fed with water quality within specifications, and properly maintained as required by the supplier. -

Nelly F/ Paul Wall, Ali & Gipp

Nelly Grillz mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: Grillz Country: UK Released: 2006 MP3 version RAR size: 1159 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1586 mb WMA version RAR size: 1471 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 468 Other Formats: MMF AHX VQF WMA FLAC AAC AU Tracklist Hide Credits Grillz (Dirty) A1 4:30 Featuring – Ali & Gipp, Paul Wall Grillz (Clean) A2 4:30 Featuring – Ali & Gipp, Paul Wall A3 Grillz (Instrumental) 4:30 Nasty Girl (New Edit (Explicit)) B1 4:52 Featuring – Avery Storm, Jagged Edge , Diddy* Tired (Album Version (Explicit)) B2 3:17 Featuring – Avery Storm Companies, etc. Pressed By – Orlake Records Credits Mastered By – NAWEED* Barcode and Other Identifiers Label Code: LC 01846 Rights Society: BIEM/SABAM Matrix / Runout: WMCST 40453-A- NAWEED OR Matrix / Runout: WMCST 40453-B- OR Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Nelly F/ Nelly F/ Paul MCST 40453 Paul Wall, Wall, Ali & Gipp - Universal MCST 40453 UK 2006 Ali & Gipp Grillz (12") Nelly Feat. Paul Nelly Feat. Wall, Ali & Gipp - none Paul Wall, Urban none Germany 2006 Grillz (12", Ali & Gipp Promo) Universal, Fo' Reel Entertainment, Nelly F/ Nelly F/ Paul B0005897-11, Derrty Ent., B0005897-11, Paul Wall, Wall, Ali & Gipp - US 2005 UNIR 21532-1 Universal, Fo' Reel UNIR 21532-1 Ali & Gipp Grillz (12") Entertainment, Derrty Ent. Nelly feat. Nelly feat. Paul Universal, Fo' Reel Paul Wall Wall & Ali & UNIR 21532-1 Entertainment, UNIR 21532-1 US 2005 & Ali & Gipp - Grillz Derrty Ent. Gipp (12", Promo) Nelly F/ Paul Nelly F/ Wall, Ali & Gipp - NGRILLZVP1 Paul Wall, Universal NGRILLZVP1 Europe 2006 Grillz (12", Ali & Gipp Promo) Related Music albums to Grillz by Nelly Nelly Feat. -

Man Depends on Former Wife for Everyday Needs

6A RECORDS/A DVICE TEXARKANA GAZETTE ✯ MONDAY, JULY 19, 2021 5-DAY LOCAL WEATHER FORECAST DEATHS Man depends on former TODAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY EUGENE CROCKETT JR. Eugene “Ollie” Crockett Jr., 69, of Ogden, AR, died Wednesday, July 14, 2021, in wife for everyday needs Ogden, AR. High-Upper 80s High-Upper 80s Mr. Dear Abby: I have been with my boy- but not yet. Low-Near 70 Low-Lower 70s Crockett was friend, “John,” for a year and a half. He had When people see me do things that are born May been divorced for two years after a 20-year considered hard work, they presume I need 19, 1952, in marriage when we got together. He told help. For instance, today I bought 30 cement THURSDAY FRIDAY Dierks, AR. He was a Car me he and his ex, “Jessica,” blocks to start building a wall. Several men Detailer. He Dear Abby were still good friends. I asked if I needed help. I refused politely as was preced- thought it was OK since I always do, saying they were thoughtful to Jeanne Phillips High-Upper 80s ed in death they were co-parenting offer but I didn’t need help. They replied, by his par- Low-Lower 70s High-Lower 90s High-Lower 90s their kid. I have children of “No problem.” Low-Lower 70s Low-Mid-70s ents, Bernice my own, and I understand. A short time later it started raining. A and Eugene Crockett Sr.; one I gave up everything and woman walked by carrying an umbrella sister, Bertha Lee Crockett; moved two hours away to and offered to help, and I responded just thunderstorms. -

May 2018 Newsletter

June 18th, 2019 Songwriters in the Round NEWSLETTER A n E n t e r t a i n m e n t I n d u s t r y O r g a n i z a t i on President’s Corner Dear Friends and Members, Our next panel discussion, “Songwriters in the Round,” is set for June 18th at The Federal in North Hollywood. Please note the different venue and the lower price. I am excited to wrap up this season by co-moderating this panel with the amazing, Mara Schwartz Kuge! We take a vacation in the month of July, but next up is our Second Annual Summer Networking Mixer at the Palihouse in West Hollywood on August 27th. Come join us for an entire evening of networking. Bring plenty of business cards and register early—you don’t want to miss this one! Lastly, please join me in thanking our 2018–2019 Board of Directors. These amazing women and men sacrifice so much of their time and energy to ensure that all of the CCC activities are planned and executed without a hitch. Some of their accomplishments are: • Amazing panel discussions with relevant content. • New format that enables the meetings to end promptly at 9pm. • Extended season that now runs from August–June. • New banking partner that offered more favorable rates and lower fees. • The Scholarship Fund is now an official 501(c)(3) non-profit charitable organization. • Producing another rousing Apollo-Award Holiday bash. Thanks for your continued support! I look forward to seeing you at a CCC event soon. -

MEET INFORMATION GATOR SOCIAL DID YOU KNOW MEET 2 BATON ROUGE, LA. What's Happening?

3 NCAA Championships ● 10 SEC Championships ● 8 with 19 NCAA Individual Titles MEET INFORMATION MEET 2 BATON ROUGE, LA. Date: Friday, Jan. 18 / 9 p.m. ET No. 3 Florida Gators No. 5 LSU Tigers Site: Pete Maravich Assembly Center (13,200) Head Coach: Jenny Rowland Head Coach: D-D Breaux Television: SEC Network Career (4th season): 43-9 Career (42nd season): 774-424-8 Video: WatchESPN At UF: same At LSU: same Live Stats: FloridaGators.com Tickets: Range in price from $12-$6. Contact LSU 2019: 1-0 / 1-0 SEC 2019: 1-1 / 0-1 SEC Ticket Office at (225) 578-2184 for more 2018 NCAA Finish: 3rd 2018 NCAA Finish: 4th information Series Record UF leads 70-40 (last meeting: UF was third (all-time): in 2018 NCAA Super Six (197.85) and What’s Happening? LSU was fourth (197.8375) Florida continues action versus Southeastern Conference “Tigers” when the Gators travel to No. 5 LSU. This is the 21st consecutive meeting both teams bring top-10 rankings. Meetings between these two teams are traditionally close. Of the GATOR SOCIAL last 20 meetings, less than a half a point was the deciding margin 17 times. Florida Gators Gymnastics The Florida-LSU dual ends the first-ever SEC Network Friday Night Heights triple-header. Olympic medalists Bart Conner Florida Gators and Kathy Johnson Clarke call the action Friday beginning at 9 p.m. @GatorsGym @FloridaGators Florida used its highest opening total (and the nation’s second-highest 2019 opening score) to take a 197.30-196.45 win over No.