Accident Prevention August 1999

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JACK RILEY and the SKYROCKETS Page 36

VOL 15 ISSUE 01 JAN 2018 cessnaflyer.org JACK RILEY AND THE SKYROCKETS page 36 Step-by-step fuel cell replacement Q&A: Backcountry tires for a 182 CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED SERVICE CHANGE Permit No. 30 No. Permit Montezuma, IA Montezuma, PAID RIVERSIDE, CA 92517 CA RIVERSIDE, U.S. Postage U.S. 5505 BOX PO Presorted Standard Presorted CESSNA FLYER ASSOCIATION FLYER CESSNA • Interior Panels and Glare Shields for Cessna 170, 175, 180, 185, 172 and early 182, U & TU 206, 207* • Nosebowls for Cessna 180, 185, Vol. 15 Issue 01 January 2018 210 and early 182 • All Products FAA Approved Repair Station No. LOGR640X The Official Magazine of Specializing in Fiberglass Aircraft Parts • Extended Baggage Kits for The Cessna Flyer Association Cessna 170 B, 172, 175, 180, 185, E-mail: [email protected] 206/207 and 1956-1980 182 www.selkirk-aviation.com • Vinyl and Wool Headliners (208) 664-9589 • Piper PA-18 Cub Cowling on field approval basis for certified aircraft Composite Cowls Available for PRESIDENT Jennifer Dellenbusch All C180, All C185 and 1956-1961 C182 *207 interiors on Field Approval basis. [email protected] VICE PRESIDENT / DIRECTOR OF SALES Kent Dellenbusch [email protected] PRODUCTION COORDINATOR Heather Skumatz CREATIVE DIRECTOR Marcus Y. Chan YES! ASSOCIATE EDITOR Scott Kinney EDITOR AT LARGE Thomas Block CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Mike Berry • Steve Ells • Kevin Garrison Michael Leighton • Dan Pimentel John Ruley • Jacqueline Shipe Dale Smith • Kristin Winter CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS IT’S CERTIFIED! Paul Bowen • James Lawrence • Keith Wilson Electroair's Electronic Ignition System P.O. Box 5505 Riverside, CA 92517 Toll-Free: 800.397.3920 Call or Text: 626.844.0125 www.cessnaflyer.org Cessna Flyer is the official publication of the Cessna Flyer Association. -

COMPANY BASED AIRCRAFT FLEET PAX EACH BAR S WEBSITE E-MAIL Pel-Air Aviation Adelaide Brisbane Melbourne Sydney Saab 340 16 34 Y

PAX BAR COMPANY BASED AIRCRAFT FLEET WEBSITE E-MAIL EACH S Adelaide Saab 340 16 34 Pel-Air Brisbane Additional access Yes www.pelair.com.au [email protected] Aviation Melbourne to REX Airline’s 50 n/a Sydney Saab aircraft Adelaide Citation CJ2 n/a 8 Brisbane Beechcraft n/a 10 Cairns Kingair B200 The Light Darwin Jet Aviation Melbourne n/a www.lightjets.com.au [email protected] Group Sydney Beechcraft Baron n/a 5 *Regional centres on request Broome Metro II n/a 12 Complete Darwin Merlin IIIC n/a 6 n/a www.casair.com.au [email protected] Aviation Jandakot Piper Navajo n/a 7 Network Fokker 100 17 100 Perth n/a www.networkaviation.com.au [email protected] Aviation A320-200 4 180 Challenger 604 1 9 Embraer Legacy n/a 13 Australian Essendon Bombardier n/a 13 Corporate Melbourne Global Express Yes www.acjcentres.com.au [email protected] Jet Centres Perth Hawker 800s n/a 8 Cessna Citation n/a 8 Ultra SA Piper Chieftain n/a 9 NSW King Air B200 n/a 10 Altitude NT n/a www.altitudeaviation.com.au [email protected] Aviation QLD Cessna Citation n/a 5-7 TAS VIC Piper Chieftain 1 7 Cessna 310 1 5 Geraldton Geraldton GA8 Airvan 4 7 n/a www.geraldtonaircharter.com.au [email protected] Air Charter Beechcraft 1 4 Bonanza Airnorth Darwin ERJ170 4 76 n/a www.airnorth.com.au [email protected] *Other cities/towns EMB120 5 30 on request Beechcraft n/a 10 Kirkhope Melbourne Kingair n/a www.kirkhopeaviation.com.au [email protected] Aviation Essendon Piper Chieftain n/a 9 Piper Navajo n/a 7 Challenger -

Uso De ELT En 406 Mhz En La Región SAM (Presentada Por Bolivia)

Organización de Aviación Civil Internacional SAR/8 SAM-NI/05 Oficina Regional Sudamericana 17/10/11 Octavo Seminario-Taller/Reunión de Implantación de Búsqueda y Salvamento de la Región SAM (SAR/8 - SAM) Asunción, Paraguay, 24 al 28 de Octubre de 2011 Cuestión 3 del Orden del día: Uso de ELT en 406 MHz en la Región SAM (Presentada por Bolivia) Resumen Esta Nota Informativa se presenta, con el objeto de que la reunión tome conocimiento del estado de aplicación de normas para el uso del ELT en Bolivia. 1 Antecedentes 1.1 La aplicación del uso del Transmisor Localizador de Emergencia (ELT) está normada en la Reglamentación Aeronáutica Boliviana (RAB 90), el operador debe garantizar que todos los ELT’s sean capaces de transmitir en 406 MHz y estén codificados de acuerdo con el Anexo 10 de la OACI, como también registrados en la DGAC y en el RCC La Paz responsable del inicio de las operaciones de Búsqueda y Salvamento, dentro el Segmento Terrestre Asignado a Chile para el Sistema COSPAS – SARSAT. 1.2 A la fecha, el 70 % de la flota de aeronaves matriculadas en el Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, disponen de equipos ELT los mismos que trabajan en la frecuencia 406 MHz, el 30 % restante, corresponde a la aviación general. 2 Análisis 2.1 El Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia a través de la DGAC, y en cumplimiento de la Reglamentación Aeronáutica Boliviana, en su parte Reglamento sobre Instrumentos y Equipos Requeridos (RAB 90), realiza la verificación del funcionamiento y equipamiento del ELT, al inicio de la certificación así como durante las inspecciones anuales, de conformidad con el formulario DGAC-AIR 8130-6, que forma parte del Manual Guía de los Inspectores AIR. -

Aerodynamic Analysis and Design of a Twin Engine Commuter Aircraft

28TH INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF THE AERONAUTICAL SCIENCES AERODYNAMIC ANALYSIS AND DESIGN OF A TWIN ENGINE COMMUTER AIRCRAFT Fabrizio Nicolosi*, Pierluigi Della Vecchia*, Salvatore Corcione* *Department of Aerospace Engineering - University of Naples Federico II [email protected]; [email protected], [email protected] Keywords: Aircraft Design, Commuter Aircraft, Aerodynamic Analysis Abstract 1. Introduction The present paper deals with the preliminary design of a general aviation Commuter 11 seat Many in the industry had anticipated 2011 to be aircraft. The Commuter aircraft market is today the year when the General Aviation characterized by very few new models and the manufacturing industry would begin to recover. majority of aircraft in operation belonging to However, the demand for business airplanes and this category are older than 35 years. Tecnam services, especially in the established markets of Aircraft Industries and the Department of Europe and North America, remained soft and Aerospace Engineering (DIAS) of the University customer confidence in making purchase of Naples "Federico II" are deeply involved in decision in these regions remained weak. This the design of a new commuter aircraft that inactivity, nonetheless, was offset in part by should be introduced in this market with very demand from the emerging markets of China good opportunities of success. This paper aims and Russia. While a full resurgence did not take to provide some guidelines on the conception of place in 2011, the year finished with signs of a new twin-engine commuter aircraft with recovery and reason of optimism. GAMA eleven passengers. Aircraft configuration and (General Aviation Manufacturer Association) cabin layouts choices are shown, also compared 2011 Statistical Databook & Industry Outlook to the main competitors. -

Descriptive Study of Aircraft Hijacking. Criminal Justice Monograph, Volume III, No

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 073 315 VT 019 207 AUTHCP Turi, Robert R.; And Others TITLE Descriptive Study of Aircraft Hijacking. Criminal Justice Monograph, Volume III, No. 5. INSTITUTION Sam Houston State Univ., Huntsville,Tex. Inst. of Contemporary Corrections and the Behavioral Sciences. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 177p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS *Aerospace Industry; Case Studies; Correctional Rehabilitation; *Criminals; Government Role; *International Crimes; *International Law;Legal' Problems; *Prevention; Program Descriptions; *Psychological Characteristics; Psychological Patterns; Security; Statistical Data IDENTIFIERS Criminal Justice; *Skyjacking ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to comprehensively describe all aspects of the phenomenonknown as "skyjacking." The latest statistics on airline hijackingare included, which were obtained through written correspondence and personalinterviews with Federal Aviation Authority officials inWashington, D. C. and Houston, Texas. Legal and technical journalsas well as government documents were reviewed, and on the basisof this review:(1) Both the national and international legalaspects of hijacking activities are provided,(2) The personality and emotional state ofthe skyjacker are examined, and (3) Preventionmeasures taken by both the government and the airline industryare discussed, including the sky marshal program, the pre-boarding screeningprocess, and current developments in electronic detection devices.The human dimensions and diverse dangers involved in aircraftpiracy are delineated. -

Aircraft Library

Interagency Aviation Training Aircraft Library Disclaimer: The information provided in the Aircraft Library is intended to provide basic information for mission planning purposes and should NOT be used for flight planning. Due to variances in Make and Model, along with aircraft configuration and performance variability, it is necessary acquire the specific technical information for an aircraft from the operator when planning a flight. Revised: June 2021 Interagency Aviation Training—Aircraft Library This document includes information on Fixed-Wing aircraft (small, large, air tankers) and Rotor-Wing aircraft/Helicopters (Type 1, 2, 3) to assist in aviation mission planning. Click on any Make/Model listed in the different categories to view information about that aircraft. Fixed-Wing Aircraft - SMALL Make /Model High Low Single Multi Fleet Vendor Passenger Wing Wing engine engine seats Aero Commander XX XX XX 5 500 / 680 FL Aero Commander XX XX XX 7 680V / 690 American Champion X XX XX 1 8GCBC Scout American Rockwell XX XX 0 OV-10 Bronco Aviat A1 Husky XX XX X XX 1 Beechcraft A36/A36TC XX XX XX 6 B36TC Bonanza Beechcraft C99 XX XX XX 19 Beechcraft XX XX XX 7 90/100 King Air Beechcraft 200 XX XX XX XX 7 Super King Air Britten-Norman X X X 9 BN-2 Islander Cessna 172 XX XX XX 3 Skyhawk Cessna 180 XX XX XX 3 Skywagon Cessna 182 XX XX XX XX 3 Skylane Cessna 185 XX XX XX XX 4 Skywagon Cessna 205/206 XX XX XX XX 5 Stationair Cessna 207 Skywagon/ XX XX XX 6 Stationair Cessna/Texron XX XX XX 7 - 10 208 Caravan Cessna 210 X X x 5 Centurion Fixed-Wing Aircraft - SMALL—cont’d. -

Aviation Program Power Point Slide Show

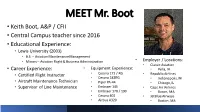

MEET Mr. Boot • Keith Boot, A&P / CFII • Central Campus teacher since 2016 • Educational Experience: • Lewis University (2003) • B.S. – Aviation Maintenance Management • Minors – Aviation Flight & Business Administration • Employer / Locations: • Classic Aviation • Career Experience: • Equipment Experience: • Pella, IA • Certified Flight Instructor • Cessna 172 / RG • Republic Airlines • Cessna 182RG • Indianapolis, IN • Aircraft Maintenance Technician • Piper PA-44 • Chicago, IL • Supervisor of Line Maintenance • Embraer 145 • Cape Air Airlines • Embraer 170 / 190 • Boson, MA • Cessna 402 • JetBlue Airways • Airbus A320 • Boston, MA Introduction to Aviation AVIATION PROGRAM • One Year (2 Semesters) • Grades 9, 10, 11, or 12 • AOPA You Can Fly Progression Track(s) Private Pilot Aviation Maintenance 1 Ground School • One Year (2 Semesters) • Grades 10, 11, or 12 • One Year (2 Semesters) • Grades 10, 11, or 12 Aviation Maintenance 2 • One Year (2 Semesters) • Grades 11, or 12 Aviation Maintenance 3 • One Year (2 Semesters) • Grade 12 AVIATION PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS • Accreditation – Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) • Unique – One of only a few high school aviation maintenance programs in the USA. • Recent Graduates/Student successes: • Private Pilot Certificate & Solo Flights • Acceptance to Lewis University & Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University • Airframe and Powerplant Certificate • A.A.S. Degree – Indian Hills Community College • Recent Awards: • Recipient of Women in Aviation JT8D Turbofan Engine donated by FedEx • Connections: • -

Loopnet, Colliers.Com and Personal Outreach

DRAFT AVIATION ADVISORY BOARD MEETING MINUTES FORT LAUDERDALE EXECUTIVE AIRPORT RED TAILS CONFERENCE ROOM 6000 NW 21 AVENUE, FORT LAUDERDALE, FLORIDA THURSDAY, JUNE 24, 2021 – 1:30 P.M. CITY OF FORT LAUDERDALE Cumulative Attendance 7/2020-6/2021 Board Members Attendance Present Absent Louis Gavin, Chair P 8 0 Mark Volchek, Vice Chair P 7 1 Jeff Johnson A 7 1 William Gilbert P 2 0 Robert Laughlin P 5 1 Wes Szymonik P 7 1 Pierre Taschereau P 8 0 Valerie Vitale A 7 1 Non-Voting Tamarac Vice Mayor P 6 2 Marlon Bolton Jeff Helyer, City of P 7 1 Oakland Park Airport Staff Rufus A. James, Airport Director Carlton Harrison, Assistant Airport Director Jeri Pryor, Program Manager I Khant Myat, Project Manager II/Airport Engineer William Ward, Airport Operations Supervisor Linda Blanco, Senior Administrative Assistant Miguel Laca, Financial Administrator Others Jarrett Kreger, MNREH Florida, LLC Tom O’Donnell, Kimley-Horn and Associates, Inc. Don Campion, Banyan Air Service, Inc. Mike Worley, JM Family Enterprises, Inc. Carlington Smith, Jet East/Gama Aviation Leonel Leon, W Aviation, LLC Jerry Jean-Phillipe, Virtual Meeting Technician J. Opperlee, Recording Secretary, Prototype, Inc. CALL TO ORDER Chair Gavin called the meeting to order at 1:30 p.m. 1 Aviation Advisory Board June 24, 2021 Page 2 Roll Call Roll was called and a quorum was determined to be present. Motion made by Mr. Taschereau, seconded by Mr. Gilbert, to allow Mr. Volchek to attend the meeting via Zoom. In a voice vote, the motion passed unanimously. Motion made by Mr. -

Flight Safety Digest June-September 1997

FLIGHT SAFETY FOUNDATION JUNE–SEPTEMBER 1997 FLIGHT SAFETY DIGEST SPECIAL ISSUE Protection Against Icing: A Comprehensive Overview Report An Urgent Safety FLIGHT SAFETY FOUNDATION For Everyone Concerned Flight Safety Digest With the Safety of Flight Vol. 16 No. 6/7/8/9 June–September 1997 Officers/Staff In This Issue Protection Against Icing: A Comprehensive Stuart Matthews Chairman, President and CEO Overview Board of Governors An Urgent Safety Report James S. Waugh Jr. The laws of aerodynamics, which make flight possible, can Treasurer be subverted in moments by a build-up of ice that in some Carl Vogt situations is barely visible. During icing conditions, ground General Counsel and Secretary deicing and anti-icing procedures become an essential Board of Governors element in safe operations. Moreover, in-flight icing issues continue to be made more complex by a growing body of ADMINISTRATIVE new knowledge, including refinements in our understanding Nancy Richards of aerodynamics and weather. Executive Secretary This unprecedented multi-issue Flight Safety Digest brings Ellen Plaugher together a variety of informational and regulatory documents Executive Support–Corporate Services from U.S. and European sources. Collectively, they offer an overview of the knowledge concerning icing-related accident FINANCIAL prevention. Brigette Adkins Documents included in this special report are from such Controller widely divergent sources as the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), the Association of European Airlines TECHNICAL (AEA), the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), the Robert H. Vandel European Joint Aviation Authorities (JAA) and the Air Line Director of Technical Projects Pilots Association, International (ALPA). In addition, pertinent articles from FSF publications have MEMBERSHIP been reprinted here. -

Cessna 172SP

CESSNA INTRODUCTION MODEL 172S NOTICE AT THE TIME OF ISSUANCE, THIS INFORMATION MANUAL WAS AN EXACT DUPLICATE OF THE OFFICIAL PILOT'S OPERATING HANDBOOK AND FAA APPROVED AIRPLANE FLIGHT MANUAL AND IS TO BE USED FOR GENERAL PURPOSES ONLY. IT WILL NOT BE KEPT CURRENT AND, THEREFORE, CANNOT BE USED AS A SUBSTITUTE FOR THE OFFICIAL PILOT'S OPERATING HANDBOOK AND FAA APPROVED AIRPLANE FLIGHT MANUAL INTENDED FOR OPERATION OF THE AIRPLANE. THE PILOT'S OPERATING HANDBOOK MUST BE CARRIED IN THE AIRPLANE AND AVAILABLE TO THE PILOT AT ALL TIMES. Cessna Aircraft Company Original Issue - 8 July 1998 Revision 5 - 19 July 2004 I Revision 5 U.S. INTRODUCTION CESSNA MODEL 172S PERFORMANCE - SPECIFICATIONS *SPEED: Maximum at Sea Level ......................... 126 KNOTS Cruise, 75% Power at 8500 Feet. ................. 124 KNOTS CRUISE: Recommended lean mixture with fuel allowance for engine start, taxi, takeoff, climb and 45 minutes reserve. 75% Power at 8500 Feet ..................... Range - 518 NM 53 Gallons Usable Fuel. .................... Time - 4.26 HRS Range at 10,000 Feet, 45% Power ............. Range - 638 NM 53 Gallons Usable Fuel. .................... Time - 6.72 HRS RATE-OF-CLIMB AT SEA LEVEL ...................... 730 FPM SERVICE CEILING ............................. 14,000 FEET TAKEOFF PERFORMANCE: Ground Roll .................................... 960 FEET Total Distance Over 50 Foot Obstacle ............... 1630 FEET LANDING PERFORMANCE: Ground Roll .................................... 575 FEET Total Distance Over 50 Foot Obstacle ............... 1335 FEET STALL SPEED: Flaps Up, Power Off ..............................53 KCAS Flaps Down, Power Off ........................... .48 KCAS MAXIMUM WEIGHT: Ramp ..................................... 2558 POUNDS Takeoff .................................... 2550 POUNDS Landing ................................... 2550 POUNDS STANDARD EMPTY WEIGHT .................... 1663 POUNDS MAXIMUM USEFUL LOAD ....................... 895 POUNDS BAGGAGE ALLOWANCE ........................ 120 POUNDS (Continued Next Page) I ii U.S. -

Preflight Inspection

STEP BY STEP IMPORTANT NOTE! . Many an aircraft accidents could have been prevented by the pilot completing an adequate preflight inspection of their aircraft before departure. The preflight inspection will initially be taught to you by your instructor and after they oversee you conducting it a few times it will become your responsibility to thoroughly check the aircraft before each flight. The inspection procedure is laid out in the POH for your aircraft. After reviewing the aircraft documents and confirming suitable weather for the trip, a thorough pre-flight inspection (or walk-around) is essential to confirm that your aircraft is airworthy. The following pre-flight inspection is an excerpt from the Cessna 152 Pilot Operating Manual. AIRCRAFT PREFLIGHT INSPECTION 3 STEP PROCESS . Best practise is to do three walkarounds: . In walkaround one, we put the master on and check the lights; pitot heat; the stall warning vane, oil and fuel. This way if we need to order fuel, it can be done now and will reduce any potential delays. In walkaround two, we select the flaps down. After they have been extended we turn the master off. In walkaround three, the master is now off thus conserving the battery, and we take our time to do a complete detailed pre-flight inspection of the aircraft as will be discussed in the ensuing pages. FLUIDS Fuel Quantity: . Check the fuel quantity for your aircraft using the dipstick stored behind the seat. Check the journey log or refueling stickers to verify if it has normal or long range tanks. You will inform your instructor regarding the fuel quantity in gallons and calculate the aircraft. -

Vol. 61 No. 3 March 2010

MDT - Department of Transportation Aeronautics Division Vol. 61 No. 3 March 2010 Target Range Students Attend Conference Montana Department of Transportation Director Jim Lynch opened the student aviation program, “Takeoff with Aviation Education” at this year’s Montana Aviation Conference held at the Hilton Garden Inn in Missoula March 5. Fifty 5th grade students from Target Range School of Missoula attended the student program. “Takeoff with Aviation Education” was presented by MDT Aeronautics Division with the help of Jeanne MacPherson and Kaye Ebelt, a 5th grade teacher at Target Range. The 50 students rotated around different aviation stations. The aviation stations included a flight simulator, final approach, thrust with propeller airplanes, a paper airplane contest, airplane diagram “name the part”, Fly the SR-71, and a famous aviators treasure hunt. The students were treated to a flight demonstration by the Big Sky Thunderbirds. Many of the exhibitors at this year’s conference contributed to the student program by offering items for the awards portion of this Jim Lynch, MDT director, is talking with the 5th grade students program. We would like to thank each of you for your from Missoula’s Target Range School. This group of 5th graders involvement with aviation education. are the “Solar Smarties” that took first place in the state robotic contest. The Solar Smarties came up with a creative solution to Missoula’s transportation problems by using solar cars. They contacted Jim Lynch by writing letters early in the year, asking for the five biggest transportation problems in Montana and especially in Missoula. Each of their letters was answered.