1 Transforming Customary, Contractual and Administrative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B E N I N Benin

Birnin o Kebbi !( !( Kardi KANTCHARIKantchari !( !( Pékinga Niger Jega !( Diapaga FADA N'GOUMA o !( (! Fada Ngourma Gaya !( o TENKODOGO !( Guéné !( Madécali Tenkodogo !( Burkina Faso Tou l ou a (! Kende !( Founogo !( Alibori Gogue Kpara !( Bahindi !( TUGA Suroko o AIRSTRIP !( !( !( Yaobérégou Banikoara KANDI o o Koabagou !( PORGA !( Firou Boukoubrou !(Séozanbiani Batia !( !( Loaka !( Nansougou !( !( Simpassou !( Kankohoum-Dassari Tian Wassaka !( Kérou Hirou !( !( Nassoukou Diadia (! Tel e !( !( Tankonga Bin Kébérou !( Yauri Atakora !( Kpan Tanguiéta !( !( Daro-Tempobré Dammbouti !( !( !( Koyadi Guilmaro !( Gambaga Outianhou !( !( !( Borogou !( Tounkountouna Cabare Kountouri Datori !( !( Sécougourou Manta !( !( NATITINGOU o !( BEMBEREKE !( !( Kouandé o Sagbiabou Natitingou Kotoponga !(Makrou Gurai !( Bérasson !( !( Boukombé Niaro Naboulgou !( !( !( Nasso !( !( Kounounko Gbangbanrou !( Baré Borgou !( Nikki Wawa Nambiri Biro !( !( !( !( o !( !( Daroukparou KAINJI Copargo Péréré !( Chin NIAMTOUGOU(!o !( DJOUGOUo Djougou Benin !( Guerin-Kouka !( Babiré !( Afekaul Miassi !( !( !( !( Kounakouro Sheshe !( !( !( Partago Alafiarou Lama-Kara Sece Demon !( !( o Yendi (! Dabogou !( PARAKOU YENDI o !( Donga Aledjo-Koura !( Salamanga Yérémarou Bassari !( !( Jebba Tindou Kishi !( !( !( Sokodé Bassila !( Igbéré Ghana (! !( Tchaourou !( !(Olougbé Shaki Togo !( Nigeria !( !( Dadjo Kilibo Ilorin Ouessé Kalande !( !( !( Diagbalo Banté !( ILORIN (!o !( Kaboua Ajasse Akalanpa !( !( !( Ogbomosho Collines !( Offa !( SAVE Savé !( Koutago o !( Okio Ila Doumé !( -

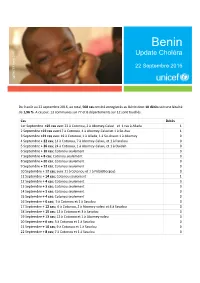

Update Choléra

Benin Update Choléra 22 Septembre 2016 @UNICEF Benin 2016 Benin @UNICEF Du 9 août au 22 septembre 2016, au total, 508 cas ont été enregistrés au Bénin dont 10 décès soit une létalité de 1,96 %. A ce jour, 13 communes sur 77 et 6 départements sur 12 sont touchés. Cas Décès 1er Septembre +25 cas avec 22 à Cotonou, 2 à Abomey-Calavi et 1 cas à Allada 1 2 Septembre +22 cas avec17 à Cotonou, 4 à Abomey-Calavi et 1 à So-Ava 1 3 Septembre +21 cas avec 19 à Cotonou, 1 à Allada, 1 à So-Ava et 1 à Abomey 0 4 Septembre + 22 cas; 14 à Cotonou, 7 à Abomey-Calavi, et 1 à Parakou 0 5 Septembre + 26 cas; 24 à Cotonou, 1 à Abomey-Calavi, et 1 à Ouidah 0 6 Septembre + 10 cas; Cotonou seulement 0 7 Septembre + 8 cas; Cotonou seulement 0 8 Septembre + 20 cas; Cotonou seulement 0 9 Septembre + 12 cas; Cotonou seulement 0 10 Septembre + 12 cas; avec 11 à Cotonou et 1 à Ndali(Borgou) 0 11 Septembre + 14 cas; Cotonou seulement 1 12 Septembre + 4 cas; Cotonou seulement 0 13 Septembre + 3 cas; Cotonou seulement 0 14 Septembre + 3 cas; Cotonou seulement 0 15 Septembre + 4 cas; Cotonou seulement 0 16 Septembre + 6 cas; 5 à Cotonou et 1 à Savalou 0 17 Septembre + 12 cas; 6 à Cotonou, 2 à Abomey-calavi et 4 à Savalou 0 18 Septembre + 15 cas; 12 à Cotonou et 3 à Savalou 0 19 Septembre + 13 cas; 12 à Cotonou et 1 à Abomey-calavi 0 20 Septembre + 6 cas; 5 à Cotonou et 1 à Savalou 0 21 Septembre + 10 cas; 9 à Cotonou et 1 à Savalou 0 22 Septembre + 8 cas; 7 à Cotonou et 1 à Savalou 0 1. -

Projet De Vulgarisation De L'aquaculture Continentale En République Du Bénin Quatrième Session Ordinaire Du Comité De Suiv

Projet de Vulgarisation de l’Aquaculture Continentale en République du Bénin Bureau du Projet / Direction des Pêches Tel: 21 37 73 47 No 004 Le 22 Juillet 2011 Email: [email protected] Un an après son démarrage en juin 2011, le Projet de Vulgarisation de l’Aquaculture Continentale en République du Bénin (PROVAC), a connu un bilan positif meublé d’activités diverses mais essentiellement axées sur les formations de pisciculteurs ordinaires par l’approche « fermier à fermier »démarré au début du mois de juin 2010, poursuit ses activités et vient d’amor‐ cer le neuvième mois de sa mise en œuvre. Quatrième session ordinaire du Comité de Suivi Le Mercredi 18 Mai 2011 s’est tenue, dans la salle de formation de la Direction des Pêches à Cotonou, la quatrième session ordinaire du Comité de Suivi du Projet de Vulgarisation de l’Aqua‐ culture Continentale en République du Bénin (PROVAC). Cette rencontre a connu la participation des membres du Comité de Suivi désignés par les quatre Centres Régionaux pour la Promotion Agricole (CeRPA) impliqués dans le Projet sur le terrain et a été rehaussée par la présence de la Représentante Résidente de la JICA au Bénin. A cette session, les CeRPA Ouémé/Plateau, Atlantique/Littoral, Zou/Collines et Mono/Couffo ont fait le point des activités du Projet sur le terrain, d’une part, et le Plan de Travail Annuel (PTA) 4e session ordinaire approuvé à Tokyo par la JICA au titre de l’année japonaise 2011 a été exposé, d’autre part, par le du Comité du Suivi Chef d’équipe des experts. -

The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte D'ivoire, and Togo

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo Public Disclosure Authorized Nga Thi Viet Nguyen and Felipe F. Dizon Public Disclosure Authorized 00000_CVR_English.indd 1 12/6/17 2:29 PM November 2017 The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo Nga Thi Viet Nguyen and Felipe F. Dizon 00000_Geography_Welfare-English.indd 1 11/29/17 3:34 PM Photo Credits Cover page (top): © Georges Tadonki Cover page (center): © Curt Carnemark/World Bank Cover page (bottom): © Curt Carnemark/World Bank Page 1: © Adrian Turner/Flickr Page 7: © Arne Hoel/World Bank Page 15: © Adrian Turner/Flickr Page 32: © Dominic Chavez/World Bank Page 48: © Arne Hoel/World Bank Page 56: © Ami Vitale/World Bank 00000_Geography_Welfare-English.indd 2 12/6/17 3:27 PM Acknowledgments This study was prepared by Nga Thi Viet Nguyen The team greatly benefited from the valuable and Felipe F. Dizon. Additional contributions were support and feedback of Félicien Accrombessy, made by Brian Blankespoor, Michael Norton, and Prosper R. Backiny-Yetna, Roy Katayama, Rose Irvin Rojas. Marina Tolchinsky provided valuable Mungai, and Kané Youssouf. The team also thanks research assistance. Administrative support by Erick Herman Abiassi, Kathleen Beegle, Benjamin Siele Shifferaw Ketema is gratefully acknowledged. Billard, Luc Christiaensen, Quy-Toan Do, Kristen Himelein, Johannes Hoogeveen, Aparajita Goyal, Overall guidance for this report was received from Jacques Morisset, Elisée Ouedraogo, and Ashesh Andrew L. Dabalen. Prasann for their discussion and comments. Joanne Gaskell, Ayah Mahgoub, and Aly Sanoh pro- vided detailed and careful peer review comments. -

Emergency Plan of Action (Epoa) Benin: Ebola Virus Disease Preparedness

Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) Benin: Ebola Virus Disease Preparedness DREF operation Operation n° MDRBJ014; Date of Issue: 27 August 2014 Glide ° Date of disaster: 20 July 2014 Operation start date: 25 August 2014 Operation end date: 27 November ( 3 months) Host National Society(ies): Benin Red Cross Society Operation budget: CHF 50,204 Number of people affected: 14 Zones at risk Number of people assisted: One Million (indirect) 141,299 (direct) N° of National Societies involved in the operation: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, Luxembourg Red Cross and Netherlands Red Cross N° of other partner organizations involved in the operation: Ministry of Health, Ministry of the Interior (through the ANPC), Plan Benin and United Nations Children’s Fund A. Situation analysis Description of the disaster In February 2014, there was an outbreak of the Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) in Guinea, which has spread to Liberia, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal and Sierra Leone causing untold hardship and hundreds of deaths in these countries. As of 27 February 2015, a total of 23,694 cases, and 9,589 deaths, which were attributed to the EVD, had been recorded across the most affected countries of Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), an outbreak of the EVD was also reported, but is considered of a different origin than that which has affected West Africa. Benin, with a population of 10,051,000 (UNCDP 2014) shares a border with Nigeria, which has been affected by the EVD, and therefore the risks presented by the epidemic to the country are high. -

Sdlao Uemoa Uicn

DiagnosticDiagnostic 4 FOR THE WEST AFRICAN COASTAL AREA THEWESTAFRICANFOR COASTAL REGIONAL SHORELINE MONITORING MONITORING SHORELINE REGIONAL STUDY AND DRAWING UP OF A UPOF STUDY ANDDRAWING REGIONAL DIAGNOSTIC MANAGEMENT SCHEME 2010 REGIONAL SHORELINE MONITORING STUDY AND DRAWING UP OF A MANAGEMENT SCHEME FOR THE WEST AFRICAN COASTAL AREA The regional study for shoreline monitoring and drawing up a development scheme for the West African coastal area was launched by UEMOA as part of the regional programme to combat coastal erosion (PRLEC – UEMOA), the subject of Regulation 02/2007/CM/UEMOA, adopted on 6 April 2007. This decision also follows on from the recommendations from the Conference of Ministers in charge of the Environment dated 11 April 1997, in Cotonou. The meeting of Ministers in charge of the environment, held on 25 January 2007, in Cotonou (Benin), approved this Regional coastal erosion programme in its conclusions. This study is implemented by the International Union for the IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature (UICN) as part of the remit of IUCN’s Marine Conservation of Nature, helps the and Coastal Programme (MACO) for Central and Western Africa, the world find pragmatic solutions to coordination of which is based in Nouakchott and which is developed our most pressing environment as a thematic component of IUCN’s Programme for Central and and development challenges. It supports scientific research, Western Africa (PACO), coordinated from Ouagadougou. manages field projects all over the world and brings governments, UEMOA is the contracting owner of the study, in this instance non-government organizations, through PRLEC – UEMOA coordination of the UEMOA United Nations agencies, Commission. -

Spatial Distribution and Risks Factors of Porcine Cysticercosis in Southern Benin Based Meat Inspection Records

International Research Journal of Microbiology (IRJM) (ISSN: 2141-5463) Vol. 4(8) pp. 188-196, September, 2013 DOI: http:/dx.doi.org/10.14303/irjm.2013.043 Available online http://www.interesjournals.org/IRJM Copyright © 2013 International Research Journals Full Length Research Paper Spatial distribution and risks factors of porcine cysticercosis in southern Benin based meat inspection records Judicaël S. E. Goussanou ab* , T. Marc Kpodekon ab , Claude Saegerman c, Eric Azagoun a, A. K. Issaka Youssao a, Souaïbou Farougou a, Nicolas Praet d, Sarah Gabriël d., Pierre Dorny d, Nicolas Korsak e aDepartment of animal Production and Heath, Ecole Polytechnique of Abomey-Calavi, University of Abomey-Calavi, Benin bLaboratory of Applied Biology, University of Abomey-Calavi, Benin cDepartment of Infectious and Parasitic Diseases, Research Unit of Epidemiology and Risk Analysis Applied to Veterinary Sciences (UREAR-ULg), Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Liège, Liège, Belgium dDepartment of Biomedical Sciences, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium eFood Sciences Department, Faculty of veterinary Medicine, University of Liège, Liège, Belgium *Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] : Tel: 0022995700449/ 0022997168992 Abstract Porcine cysticercosis, which is widely distributed in Africa, causes financial losses and diseases among humans. To control the disease in an area, it is important to know the geographical distribution. In this study, spatial distribution of porcine cysticercosis in southern Benin was performed. By using the number of partial organ seizures at meat inspection, the study has revealed high risks of porcine cysticercosis in administrative districts of Aplahoue, Dogbo, Klouekanme and Lokossa. The proportion of seizures ranged from 0.06% for neck muscles to 0.69% for tongues. -

Monographie Des Départements Du Zou Et Des Collines

Spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin : Monographie des départements du Zou et des Collines Note synthèse sur l’actualisation du diagnostic et la priorisation des cibles des communes du département de Zou Collines Une initiative de : Direction Générale de la Coordination et du Suivi des Objectifs de Développement Durable (DGCS-ODD) Avec l’appui financier de : Programme d’appui à la Décentralisation et Projet d’Appui aux Stratégies de Développement au Développement Communal (PDDC / GIZ) (PASD / PNUD) Fonds des Nations unies pour l'enfance Fonds des Nations unies pour la population (UNICEF) (UNFPA) Et l’appui technique du Cabinet Cosinus Conseils Tables des matières 1.1. BREF APERÇU SUR LE DEPARTEMENT ....................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1. INFORMATIONS SUR LES DEPARTEMENTS ZOU-COLLINES ...................................................................................... 6 1.1.1.1. Aperçu du département du Zou .......................................................................................................... 6 3.1.1. GRAPHIQUE 1: CARTE DU DEPARTEMENT DU ZOU ............................................................................................... 7 1.1.1.2. Aperçu du département des Collines .................................................................................................. 8 3.1.2. GRAPHIQUE 2: CARTE DU DEPARTEMENT DES COLLINES .................................................................................... 10 1.1.2. -

Monographie De La Commune De Adjarra

REPUBLIQUE DU BENIN MISSION DEDEDE DECENTRALISATION ------- PPPROGRAMME D ’A’A’A PPUI AU DDDEMARRAGE DES CCCOMMUNES MONOGRAPHIE DE LA COMMUNE D’ADJARRA Consultant GANDONOU Basile Marius Ingénieur Agro-économiste Sous la supervision de M. Emmanuel GUIDIBIGUIDIBI, Directeur Général du Cabinet « Afrique Conseil » Mars 2006 Monographie de Adjarra, AFRIQUE CONSEIL, Mars 2006 SOMMAIRE SIGLES ET ABREVIATIOABREVIATIONSNSNSNS................................................................................... ................................................................................................ ................... 444 CARTESCARTES................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ................................................................................................ ....................... 666 GRAPHESGRAPHES................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ............................................................................................... .................. 666 TABLEAUX ................................................................................... ................................................................................................ ........................................................................................... -

Sdac Finale Lokossa

REPUBLIQUE DU BENIN *-*-*-*-* MINISTERE DE LA DECENTRALISATION, DE LA GOUVERNANCE LOCALE, DE L’ADMINISTRATION ET DE L’AMENAGEMENT DU TERRITOIRE (MDGLAAT) *-*-*-*-**-*-*-*-* DEPARTEMENT DU MONO *-*-*-*-* COMMUNE DE LOKOSSA Schéma Directeur d’Aménagement Communal (SDAC) de Lokossa VERSION FINALE Appui technique et financier : PDDC/GiZ Réalisé par le cabinet Alpha et Oméga Consultants 08 BP1132 tri postal ; Tél. 21 31 60 46 03BP703 ; Tél. : (+229) 21 35 32 50 COTONOU Décembre 2011 1 Sommaire 1 Rappel de la synthèse du diagnostic et de la problématique d’aménagement et de développement ....................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Synthèse générale du diagnostic de la commune de Lokossa ................................................ 5 1.1.1 Situation de la commune de Lokossa .............................................................................. 5 1.1.2 Brève description du milieu physique et naturel de la commune de Lokossa ................ 7 1.1.3 Brève description du milieu humain ............................................................................... 9 1.1.4 Caractéristiques économiques de la commune ............................................................ 10 1.1.5 Les niveaux d’équipement et de service ....................................................................... 11 1.2 Etat de l’aménagement du territoire de la commune de Lokossa ........................................ 15 1.2.1 Accessibilité de la commune ........................................................................................ -

Evaluation Report Standard Format

ÉVALUATIONS A POSTERIORI DES PROJETS FINANCÉS PAR LE FONDS DES NATIONS UNIES POUR LA DÉMOCRATIE Contrat NO.PD:C0110/10 RAPPORT D’ÉVALUATION UDF-BEN-09-287- Participation citoyenne pour l’amélioration de la gouvernance locale (Bénin) Date: 20 Janvier 2014 Executive Summary in English Remerciements L’équipe responsable de la mission remercie tous les membres d’ALCRER qui ont contribué avec dévouement et disponibilité au bon déroulement de l’organisation de cette mission de terrain au Benin. L’équipe remercie en particulier Martin ASSOGBA, Président d’ALCRER ainsi que Gervais LOKO et GANDEMEY Luc, consultants chargés de l’exécution et du suivi du projet, qui ont facilité les principaux contacts à Cotonou et dans les communes de Ouinhi, Bohicon, Abomey dans le Département du Zou et dans les Communes de Houéyogbé et de Lokossa dans le Département du Mono-Couffo. Ils ont pu rester disponibles et en contact régulier avec les consultants pendant la phase cruciale de rédaction du présent rapport. Les évaluateurs souhaitent également remercier tous les acteurs, intervenants et bénéficiaires qui ont participé à ce processus d’évaluation, qui ont accepté d’être disponibles et de partager leurs expériences et réflexions. Décharge Le contenu de la présente publication relève de la seule responsabilité des évaluateurs et ne peut en aucun cas être considéré comme reflétant l’avis du FNUD, Transtec ou d’autres institutions et/ou personnes mentionnées dans ce rapport. Auteurs Ce rapport est rédigé par Florence Burban, Ignace Djenontin et Aurélie Ferreira qui a fourni les conseils méthodologiques et éditoriaux et assuré le contrôle qualité avec le support du responsable Evaluation. -

Projet ’’EDEJROMÉDÉ’’ Renforcement Des Capacités Entrepreneuriales D’Un Groupe De Femmes Maraîchères D’Adjarra Au Bénin

6 rue Truillot Honvié, Adjarra - Bénin 94 200 IVRY/SEINE www.gref.asso.fr www.solidatic.org [email protected] [email protected] Projet ’’EDEJROMÉDÉ’’ Renforcement des capacités entrepreneuriales d’un groupe de femmes maraîchères d’Adjarra au Bénin Arrosage du compost entreposé sur la plateforme 1 SOMMAIRE Introduction Chapitre I Le contexte du Projet …………………………….. 3-9 Chapitre II Nos partenaires …………………………………….. 10-11 Chapitre III La Logique d’intervention ………………….. 11-12 Chapitre IV Les résultats attendus ………………………… 12-13 Chapitre V Les moyens dédiés au projet …………………. 14 Chapitre VI La viabilité du projet …………………………… ….. 14-15 Chapitre VII L’évaluation du projet……………………………… 15 Chapitre VIII Processus de capitalisation …………………… 15-16 Chapitre IX Implication du/des bailleurs …………………. 16 Chapitre X Chronogramme ………………………………………… 17 2 Au sud du Bénin dans le village de Drogbo, situé sur la commune d’Adjarra un groupe de femmes pratique le maraîchage. Les femmes ont donné le nom de « EDEJROMÉDÉ » à leur groupement, ce qui signifie « jardin ouvert » en langue fon. Toutefois, par manque de formation, d’organisation efficace, d’outils adaptés et du fait d’un système d’irrigation défaillant, la production est faible. Les femmes sont volontaires et ouvertes au changement et au développement de leur activité d’autant que le site sur lequel l’activité se déroule offre de nombreuses potentialités. Il s’agit à travers ce projet, conjointement avec l’association partenaire béninoise Solidatic, de soutenir l’entreprenariat féminin de ce groupement en développant la production agricole dans un pays où elle est déficitaire. Augmenter, diversifier la production agro-écologique dans le respect de l’environnement permettra aux femmes d’améliorer leur niveau de vie et d’atteindre l’autonomie alimentaire.