Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weaponized Humor: the Cultural Politics Of

WEAPONIZED HUMOR: THE CULTURAL POLITICS OF TURKISH-GERMAN ETHNO-COMEDY by TIM HÖLLERING B.A. Georg-August Universität Göttingen, 2008 M.Ed., Georg-August Universität Göttingen, 2010 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Germanic Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) June 2016 © Tim Höllering, 2016 Abstract My thesis aims to show how the humor of Turkish-German ethno-comedians fulfills a double purpose of entertaining its audience while advancing a cultural political agenda that Kathrin Bower called “transnational humanism.” It includes notions of human rights consensus, critical self-reflection, respect, tolerance, and openness to cultural diversity. Promoting these values through comedy, the artists hope to contribute to abating prejudice and discrimination in Germany’s multi-ethnic society. Fusing the traditional theatrical principle of “prodesse et delectare” with contemporary cultural politics, these comedians produce something of political relevance: making their audience aware of its conceptions of “self” and “other” and fostering a sense of community across diverse cultural identifications. My thesis builds mainly on the works of Kathrin Bower, Maha El Hissy, Erol Boran, Deniz Göktürk, and Christie Davies. Whereas Davies denies humor’s potential for cultural impact, Göktürk elucidates its destabilizing power in immigrant films. Boran elaborates this function for Turkish-German Kabarett. El Hissy connects Kabarett, film, and theater of polycultural artists and ties them to Bakhtin’s concept of the carnivalesque and the medieval jester. Bower published several essays on the works of ethno-comedians as humorous catalysts for advancing a multiethnic Germany. -

Nazi Germany and the Jews Ch 3.Pdf

AND THE o/ w VOLUME I The Years of Persecution, i933~i939 SAUL FRIEDLANDER HarperCollinsPííMí^ers 72 • THE YEARS OF PERSECUTION, 1933-1939 dependent upon a specific initial conception and a visible direction. Such a CHAPTER 3 conception can be right or wrong; it is the starting point for the attitude to be taken toward all manifestations and occurrences of life and thereby a compelling and obligatory rule for all action."'^'In other words a worldview as defined by Hitler was a quasi-religious framework encompassing imme Redemptive Anti-Semitism diate political goals. Nazism was no mere ideological discourse; it was a political religion commanding the total commitment owed to a religious faith."® The "visible direction" of a worldview implied the existence of "final goals" that, their general and hazy formulation notwithstanding, were sup posed to guide the elaboration and implementation of short-term plans. Before the fall of 1935 Hitler did not hint either in public or in private I what the final goal of his anti-Jewish policy might be. But much earlier, as On the afternoon of November 9,1918, Albert Ballin, the Jewish owner of a fledgling political agitator, he had defined the goal of a systematic anti- the Hamburg-Amerika shipping line, took his life. Germany had lost the Jewish policy in his notorious first pohtical text, the letter on the "Jewish war, and the Kaiser, who had befriended him and valued his advice, had question" addressed on September 16,1919, to one Adolf Gemlich. In the been compelled to abdicate and flee to Holland, while in Berlin a republic short term the Jews had to be deprived of their civil rights: "The final aim was proclaimed. -

Versailles (Hellerau, 1927). Even Deutschland, Frankreich Und

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Most of the sources on German history from 1890 to the end of the Weimar Republic are of use in a study of Maximilian Har den. In the following paragraphs are noted, besides the un published sources, only the published materials that deal directly with Harden, and the general works or monographs on the period that have been used most extensively. Many works cited in the text are not listed here; a complete reference to each one is found in its first citation. The indispensable source of information on Harden is the magazine he edited from 1892 until 1922. The one hundred and eighteen volumes of the Zukunft contain the bulk of his essays, commentaries, and trial records, as well as many private letters to and from him. The Zukunft was the inspiration or the source for Harden's principal pamphlets and books, namely Kampfge nosse Sudermann (Berlin, 1903); KopJe (4 vols., Berlin, 1911-1924); Krieg und Friede (2 vols., Berlin, 1918); and Von Versailles nach Versailles (Hellerau, 1927). Even Deutschland, Frankreich und England (Berlin, 1923), written after the Zukun}t had ceased publication, was in large a repetition of Zukunft articles. Harden's earliest work, Berlin als Theaterhauptstadt (Berlin, 1889), consisted in part of pieces he had written for Die Nation. Apostata (Berlin, 1892), Apostata, neue Folge (Berlin, 1892), andLiteraturund Theater (Berlin, 1896), were collections of his essays from Die Gegenwart. The Gegenwart and the other magazines for which he wrote before 1892 - Die Nation, Die Kunstwart, and M agazin fur Litteratur - are also indispensable sources. Harden's published writings also include articles in other German and foreign newspapers and magazines. -

CABARET and ANTIFASCIST AESTHETICS Steven Belletto

CABARET AND ANTIFASCIST AESTHETICS Steven Belletto When Bob Fosse’s Cabaret debuted in 1972, critics and casual viewers alike noted that it was far from a conventional fi lm musical. “After ‘Cabaret,’ ” wrote Pauline Kael in the New Yorker , “it should be a while before per- formers once again climb hills singing or a chorus breaks into song on a hayride.” 1 One of the fi lm’s most striking features is indeed that all the music is diegetic—no one sings while taking a stroll in the rain, no one soliloquizes in rhyme. The musical numbers take place on stage in the Kit Kat Klub, which is itself located in a specifi c time and place (Berlin, 1931).2 Ambient music comes from phonographs or radios; and, in one important instance, a Hitler Youth stirs a beer-garden crowd with a propagandistic song. This directorial choice thus draws attention to the musical numbers as musical numbers in a way absent from conventional fi lm musicals, which depend on the audience’s willingness to overlook, say, why a gang mem- ber would sing his way through a street fi ght. 3 In Cabaret , by contrast, the songs announce themselves as aesthetic entities removed from—yet expli- cable by—daily life. As such, they demand attention as aesthetic objects. These musical numbers are not only commentaries on the lives of the var- ious characters, but also have a signifi cant relationship to the fi lm’s other abiding interest: the rise of fascism in the waning years of the Weimar Republic. -

Goodbye to Berlin: Erich Kästner and Christopher Isherwood

Journal of the Australasian Universities Language and Literature Association ISSN: 0001-2793 (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/yjli19 GOODBYE TO BERLIN: ERICH KÄSTNER AND CHRISTOPHER ISHERWOOD YVONNE HOLBECHE To cite this article: YVONNE HOLBECHE (2000) GOODBYE TO BERLIN: ERICH KÄSTNER AND CHRISTOPHER ISHERWOOD, Journal of the Australasian Universities Language and Literature Association, 94:1, 35-54, DOI: 10.1179/aulla.2000.94.1.004 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1179/aulla.2000.94.1.004 Published online: 31 Mar 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 33 Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=yjli20 GOODBYE TO BERLIN: ERICH KASTNER AND CHRISTOPHER ISHERWOOD YVONNE HOLBECHE University of Sydney In their novels Fabian (1931) and Goodbye to Berlin (1939), two writers from different European cultures, Erich Mstner and Christopher Isherwood, present fictional models of the Berlin of the final years of the Weimar Republic and, in Isherwood's case, the beginning of the Nazi era as wel1. 1 The insider Kastner—the Dresden-born, left-liberal intellectual who, before the publication ofFabian, had made his name as the author not only of a highly successful children's novel but also of acute satiric verse—had a keen insight into the symptoms of the collapse of the republic. The Englishman Isherwood, on the other hand, who had come to Berlin in 1929 principally because of the sexual freedom it offered him as a homosexual, remained an outsider in Germany,2 despite living in Berlin for over three years and enjoying a wide range of contacts with various social groups.' At first sight the authorial positions could hardly be more different. -

Download Download

83 Jonathan Zatlin links: Jonathan Zatlin rechts: Guilt by Association Guilt by Association Julius Barmat and German Democracy* Abstract Although largely forgotten today, the so-called “Barmat Affair” resulted in the longest trial in the Weimar Republic’s short history and one of its most heated scandals. The antidemocratic right seized upon the ties that Julius Barmat, a Jewish businessman of Ukrainian provenance, maintained to prominent socialists to discredit Weimar by equat- ing democracy with corruption, corruption with Jews, and Jews with socialists. The left responded to the right’s antidemocratic campaign with reasoned refutations of the idea that democracy inevitably involved graft. Few socialist or liberal politicians, however, responded to the right’s portrayal of Weimar as “Jewish.” The failure of the left to identify antisemitism as a threat to democracy undermined attempts to democratize the German judiciary and ultimately German society itself. And then it started like a guilty thing Upon a fearful summons.1 In a spectacular operation on New Year’s Eve 1924, the Berlin state prosecutor’s office sent some 100 police officers to arrest Julius Barmat and two of his four brothers. With an eye toward capturing headlines, the prosecutors treated Barmat as a dangerous criminal, sending some 20 policemen to arrest him, his wife, and his 13-year old son in his villa in Schwanenwerder, an exclusive neighbourhood on the Wannsee. The police even brought along a patrol boat to underscore their concern that Barmat might try to escape custody via the river Havel. The arrests of Barmat’s leading managers and alleged co-conspirators over the next few days were similarly sensational and faintly ridiculous. -

The Plays in Translation

The Plays in Translation Almost all the Hauptmann plays discussed in this book exist in more or less acceptable English translations, though some are more easily available than others. Most of his plays up to 1925 are contained in Ludwig Lewisohn's 'authorized edition' of the Dramatic Works, in translations by different hands: its nine volumes appeared between 1912 and 1929 (New York: B.W. Huebsch; and London: M. Secker). Some of the translations in the Dramatic Works had been published separately beforehand or have been reprinted since: examples are Mary Morison's fine renderings of Lonely Lives (1898) and The Weavers (1899), and Charles Henry Meltzer's dated attempts at Hannele (1908) and The Sunken Bell (1899). More recent collections are Five Plays, translated by Theodore H. Lustig with an introduction by John Gassner (New York: Bantam, 1961), which includes The Beaver Coat, Drayman Henschel, Hannele, Rose Bernd and The Weavers; and Gerhart Hauptmann: Three Plays, translated by Horst Frenz and Miles Waggoner (New York: Ungar, 1951, 1980), which contains 150 The Plays in Translation renderings into not very idiomatic English of The Weavers, Hannele and The Beaver Coat. Recent translations are Peter Bauland's Be/ore Daybreak (Chapel HilI: University of North Carolina Press, 1978), which tends to 'improve' on the original, and Frank Marcus's The Weavers (London: Methuen, 1980, 1983), a straightforward rendering with little or no attempt to convey the linguistic range of the original. Wedekind's Spring Awakening can be read in two lively modem translations, one made by Tom Osbom for the Royal Court Theatre in 1963 (London: Calder and Boyars, 1969, 1977), the other by Edward Bond (London: Methuen, 1980). -

* Hc Omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1

* hc omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1 Film Architecture and the Transnational Imagination: Set Design in 1930s European Cinema presents for the first time a comparative study of European film set design in HARRIS AND STREET BERGFELDER, IMAGINATION FILM ARCHITECTURE AND THE TRANSNATIONAL the late 1920s and 1930s. Based on a wealth of designers' drawings, film stills and archival documents, the book FILM FILM offers a new insight into the development and signifi- cance of transnational artistic collaboration during this CULTURE CULTURE period. IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION European cinema from the late 1920s to the late 1930s was famous for its attention to detail in terms of set design and visual effect. Focusing on developments in Britain, France, and Germany, this book provides a comprehensive analysis of the practices, styles, and function of cine- matic production design during this period, and its influence on subsequent filmmaking patterns. Tim Bergfelder is Professor of Film at the University of Southampton. He is the author of International Adventures (2005), and co- editor of The German Cinema Book (2002) and The Titanic in Myth and Memory (2004). Sarah Street is Professor of Film at the Uni- versity of Bristol. She is the author of British Cinema in Documents (2000), Transatlantic Crossings: British Feature Films in the USA (2002) and Black Narcis- sus (2004). Sue Harris is Reader in French cinema at Queen Mary, University of London. She is the author of Bertrand Blier (2001) and co-editor of France in Focus: Film -

Trude Hesterberg She Opened Her Own Cabaret, the Wilde Bühne, in 1921

Hesterberg, Trude Trude Hesterberg she opened her own cabaret, the Wilde Bühne, in 1921. She was also involved in a number of film productions in * 2 May 1892 in Berlin, Deutschland Berlin. She performed in longer guest engagements in Co- † 31 August 1967 in München, Deutschland logne (Metropol-Theater 1913), alongside Massary at the Künstlertheater in Munich and in Switzerland in 1923. Actress, cabaret director, soubrette, diseuse, operetta After the Second World War she worked in Munich as singer, chanson singer theater and film actress, including as Mrs. Peachum in the production of The Threepenny Opera in the Munich „Kleinkunst ist subtile Miniaturarbeit. Da wirkt entwe- chamber plays. der alles oder nichts. Und dennoch ist sie die unberechen- Biography barste und schwerste aller Künste. Die genaue Wirkung eines Chansons ist nicht und unter gar keinen Umstän- Trude Hesterberg was born on 2 May, 1892 in Berlin den vorauszusagen, sie hängt ganz und gar vom Publi- “way out in the sticks” in Oranienburg (Hesterberg. p. 5). kum ab.“ (Hesterberg. Was ich noch sagen wollte…, S. That same year, two events occurred in Berlin that would 113) prove of decisive significance for the life of Getrude Joh- anna Dorothea Helen Hesterberg, as she was christened. „Cabaret is subtle work in miniature. Either everything Firstly, on on 20 August, Max Skladonowsky filmed his works or nothing does. And it is nonetheless the most un- brother Emil doing gymnastics on the roof of Schönhau- predictable and difficult of the arts. The precise effect of ser Allee 148 using a Bioscop camera, his first film record- a chanson is not foreseeable under any circumstances; it ing. -

Circling Opera in Berlin by Paul Martin Chaikin B.A., Grinnell College

Circling Opera in Berlin By Paul Martin Chaikin B.A., Grinnell College, 2001 A.M., Brown University, 2004 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Program in the Department of Music at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May 2010 This dissertation by Paul Martin Chaikin is accepted in its present form by the Department of Music as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date_______________ _________________________________ Rose Rosengard Subotnik, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date_______________ _________________________________ Jeff Todd Titon, Reader Date_______________ __________________________________ Philip Rosen, Reader Date_______________ __________________________________ Dana Gooley, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date_______________ _________________________________ Sheila Bonde, Dean of the Graduate School ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank the Deutsche Akademische Austauch Dienst (DAAD) for funding my fieldwork in Berlin. I am also grateful to the Institut für Musikwissenschaft und Medienwissenschaft at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin for providing me with an academic affiliation in Germany, and to Prof. Dr. Christian Kaden for sponsoring my research proposal. I am deeply indebted to the Deutsche Staatsoper Unter den Linden for welcoming me into the administrative thicket that sustains operatic culture in Berlin. I am especially grateful to Francis Hüsers, the company’s director of artistic affairs and chief dramaturg, and to Ilse Ungeheuer, the former coordinator of the dramaturgy department. I would also like to thank Ronny Unganz and Sabine Turner for leading me to secret caches of quantitative data. Throughout this entire ordeal, Rose Rosengard Subotnik has been a superlative academic advisor and a thoughtful mentor; my gratitude to her is beyond measure. -

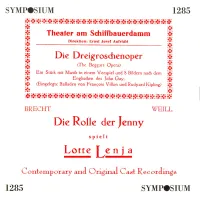

4601553-3Aa246-Booklet-SYMP1285

SYMPOSIUM RECORDS CD 1285 MUSIK IN DER WEIMAR REPUBLIK Brecht Die Dreigroschenoper Weill There is an interesting entry for Thursday, 27th September 1928 in Count Harry Kessler’s Diary of a Cosmopolitan, “In the evening saw Brecht’s Dreigroschenoper, music by Weill. A fascinating production, with rudimentary staging in the Piscator style. Weill’s music is catchy and expressive and the players (Harald Paulsen, Rosa Valetti, and so on) are excellent. It is the show of the season, always sold out: ‘You must see it!’”. Perhaps this diary note by an acute observer of the Berlin scene should be framed between two further references. In Before the Deluge, published in 1972, Otto Friedrich (an equally keen observer, he also wrote the introduction to the Kessler volume) commented laconically how “the opening night was a legendary triumph, and of every ten Berliners alive today, at least three claim to have been in the cheering audience”. Kessler’s editor comments that the work made Brecht’s name, and adds that “some of the tunes by Kurt Weill are still sung”. During the last part of the twentieth century, there was a growing interest in ‘rediscovering’ apparently neglected, or forgotten, music. Particular attention has been given to the genre attacked by the Nazis as “Entartete Musik” (degenerate music) of which the compositions of Weill were chosen as prime examples. In January 2000 the BBC celebrated the centenary of Weill’s birth and the fiftieth anniversary of his death by sponsoring a festival at the Barbican focusing on his less familiar works. Popular and media reception was rapturous. -

PDF Downloaden

Volkswirtschaft und Theater: Ernst und Spiel, Brotarbeit und Zirkus, planmäßige Geschäftigkeit und Geschäftlichkeit und auf der anderen Seite Unterhaltung und Vergnügen! Und doch hat eine jahrhundertelange Entwicklung ein Band, beinahe eine Kette zwischen beiden geschaffen, gehämmert und geschmiedet. Max Epstein1 The public has for so long seen theatrical amusements carried on as an industry, instead of as an art, that the disadvantage of apply- ing commercialism to creative work escapes comment, as it were, by right of custom. William Poel2 4. Theatergeschäft Theater als Geschäft – das scheint heute zumindest in Deutschland, wo fast alle Theater vom Staat subventioniert werden, ein Widerspruch zu sein. Doch schon um 1900 waren für die meisten deutschen Intellektuellen Geschäft und Theater, Kunst und Kommerz unvereinbare Gegensätze. Selbst für jemanden, der so inten- siv und über lange Jahre hinweg als Unternehmer, Anwalt und Journalist mit dem Geschäftstheater verbunden war wie Max Epstein, schlossen sie einander letztlich aus. Obwohl er lange gut am Theater verdient hatte, kam er kurz vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg zu dem Schluss: „Das Theatergeschäft hat die Bühnenkunst ruiniert“.3 In Großbritannien hingegen, wo Theater seit der Zeit Shakespeares als private, kommerzielle Unternehmen geführt wurden, war es völlig selbstverständlich, im Theater eine Industrie zu sehen. Der Schauspieler, Direktor und Dramatiker Wil- liam Poel bezeugte diese Haltung und war zugleich einer der ganz wenigen, der sie kritisierte. Wie auch immer man den Prozess bewertete, Tatsache war, dass Theater in der Zeit der langen Jahrhundertwende in London wie in Berlin überwiegend kom- merziell angeboten wurde. Zwar gilt dies teilweise bereits für die frühe Neuzeit, erst im Laufe des 19.