The Beaumont Race Riot, 1943

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Formal and Informal School Structures Support Gender

Helping Double Rainbows Shine: How Formal and Informal School Structures Support Gender Diverse Youth on the Autism Spectrum Shelley M. Barber A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2020 Reading Committee: Kristen Missall, Chair Felice Orlich Carly Roberts Ilene Schwartz Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Education ©Copyright 2020 Shelley M. Barber University of Washington Abstract Helping Double Rainbows Shine: How Formal and Informal School Structures Support Gender Diverse Youth on the Autism Spectrum Shelley M. Barber Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Kristen Missall School Psychology, College of Education Ten adolescents (14 through 19 years old) diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) who identify as transgender/gender diverse were interviewed to better understand their perceptions and interpretations of school experiences as part of a basic qualitative study. Participants were asked to reflect on what helped them feel safe and supported in terms of their gender identity at school, what led them to feel unsafe and unsupported, and what they thought could be put in place to better support their gender identities. Table of Contents Acknowledgments............................................................................................................ i Chapter 1: Introduction .................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 2: Literature Review ........................................................................................ -

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers Asian Native Asian Native Am. Black Hisp Am. Total Am. Black Hisp Am. Total ALABAMA The Anniston Star........................................................3.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 6.1 Free Lance, Hollister ...................................................0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 12.5 The News-Courier, Athens...........................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Lake County Record-Bee, Lakeport...............................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Birmingham News................................................0.7 16.7 0.7 0.0 18.1 The Lompoc Record..................................................20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 The Decatur Daily........................................................0.0 8.6 0.0 0.0 8.6 Press-Telegram, Long Beach .......................................7.0 4.2 16.9 0.0 28.2 Dothan Eagle..............................................................0.0 4.3 0.0 0.0 4.3 Los Angeles Times......................................................8.5 3.4 6.4 0.2 18.6 Enterprise Ledger........................................................0.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Madera Tribune...........................................................0.0 0.0 37.5 0.0 37.5 TimesDaily, Florence...................................................0.0 3.4 0.0 0.0 3.4 Appeal-Democrat, Marysville.......................................4.2 0.0 8.3 0.0 12.5 The Gadsden Times.....................................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Merced Sun-Star.........................................................5.0 -

P. Diddy with Usher I Need a Girl Pablo Cruise Love Will

P Diddy Bad Boys For Life P Diddy feat Ginuwine I Need A Girl (Part 2) P. Diddy with Usher I Need A Girl Pablo Cruise Love Will Find A Way Paladins Going Down To Big Mary's Palmer Rissi No Air Paloma Faith Only Love Can Hurt Like This Pam Tillis After A Kiss Pam Tillis All The Good Ones Are Gone Pam Tillis Betty's Got A Bass Boat Pam Tillis Blue Rose Is Pam Tillis Cleopatra, Queen Of Denial Pam Tillis Don't Tell Me What To Do Pam Tillis Every Time Pam Tillis I Said A Prayer For You Pam Tillis I Was Blown Away Pam Tillis In Between Dances Pam Tillis Land Of The Living, The Pam Tillis Let That Pony Run Pam Tillis Maybe It Was Memphis Pam Tillis Mi Vida Loca Pam Tillis One Of Those Things Pam Tillis Please Pam Tillis River And The Highway, The Pam Tillis Shake The Sugar Tree Panic at the Disco High Hopes Panic at the Disco Say Amen Panic at the Disco Victorious Panic At The Disco Into The Unknown Panic! At The Disco Lying Is The Most Fun A Girl Can Have Panic! At The Disco Ready To Go Pantera Cemetery Gates Pantera Cowboys From Hell Pantera I'm Broken Pantera This Love Pantera Walk Paolo Nutini Jenny Don't Be Hasty Paolo Nutini Last Request Paolo Nutini New Shoes Paolo Nutini These Streets Papa Roach Broken Home Papa Roach Last Resort Papa Roach Scars Papa Roach She Loves Me Not Paper Kites Bloom Paper Lace Night Chicago Died, The Paramore Ain't It Fun Paramore Crush Crush Crush Paramore Misery Business Paramore Still Into You Paramore The Only Exception Paris Hilton Stars Are Bliind Paris Sisters I Love How You Love Me Parody (Doo Wop) That -

Community Involvement Plan April 2003

Star Lake Canal Superfund Site Jefferson County, Texas Community Involvement Plan April 2003 U. S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY REGION 6 002674 CONTENTS Section Page 1 Introduction .......................................................... 1 2 Site Background and Status .............................................. 3 Site Description and History ....................................... 3 National Priorities List ........................................... 4 Enforcement Program Activities .................................... 4 Current and Upcoming Site Activities ............................... 5 Site Map ...................................................... 6 3 Community Involvement Background ..................................... 7 Community Profile .............................................. 7 Community Issues, Concerns, and Information Needs .............................................. 7 4 Community Involvement Program ........................................ 9 Community Involvement Objectives ................................. 9 Community Involvement Activities and Tools ......................... 9 Community Involvement Program Schedule ......................... 13 Appendices A Superfund Glossary ................................................... 14 B Community Involvement Plan Interview Questionnaire ....................... 16 C Contact List......................................................... 17 D Community Involvement Program Schedule ................................ 21 Star Lake Canal Site Community Involvement Plan -

Start Time: 7:32 Teton Gravity Research Partnership the Quest

Directors in Attendance: Kurt Giesselman, Ken Stone, Tyler Newman, Gary Pierson, Scott Clarkson Staff: John Norton, Laurel Runcie, Daniel Kreykes, Andrew Sandstrom, Jeff Moffett On phone: Wynn Williams Guest: Chris Ledoulis Start time: 7:32 President’s Update Kurt Giesselman -We have a quorum. -Move to approve keeping same slate of officers. -Approval of January Minutes. -New Board member introduction to Wynn Williams and Tyler Newman. Teton Gravity Research Partnership Summary: 350k for 2017 and 450k for 2018. This will put us at the same partnership level as Jackson Hole and Switzerland. Discussion: We will have major web presence, film inclusion 2018, summer bike test, and 20,000 new guest entries per year from the film tour. Our brand will be aligned with a trusted industry partner in TGR. Follow up: Bring forward updated budget so the process can move forward. The Quest Summary: How can we keep people coming back with the CBGtrails app? The Quest will track the trails that you have ridden during the summer. Hit mile marker benchmarks, win prizes. 80k to move forward. th th Discussion: We are trying to give people a reason to keep coming back a 4 or 5 time. This also differentiates us from other destinations. Follow up: Bring revised budget so that we can move forward. Look into 3 or more-year agreement in the contracting process. Air update Summary: Dallas, Houston, Denver, all down. Chicago and LA have improved, but payouts will still be huge. What do we need to do in the future to minimize our payouts? Discussion: In short, there is no good answer. -

Alternative Currents in Dallas's Religious Traditions

Swimming in Other Streams Alternative Currents in Dallas's Religious Traditions BY J. GoRDON MELTON ~e are two ways oflooking at religion in the state oITexas. In the first instance, we begin with the singular dominance ofTexas by just three religious groups-the Southern Baptists, T the United Methodists, and the Roman Catholics.Their membership accounts for about half argue, of the state's population, with a few additional groups-the Churches of Christ, the National ICan r Baptists (three groups), the African Methodists (three groups), the Presbyterians, two Lutheran partict groups, the Episcopalians, and several Pentecostal groups-filling out the next tier of religious is hon Texans. One could tell the story of Texas religion by limiting the account to these dozen group ~ anoth( groups and do very little, if any, injustice to it. some Additionally, this approach reflects the reality of religion at the national level, where over and sy half of the American population has chosen to be members of a mere twenty-five Christian larger denominations, each of which has at least one million members. Upon examination they gory a the L; are seen to represent the current spectrum of Christian belief and practice. Their position is set of strengthened by considering the forty additional denominations that have at least 100,000 them members and which also present the san1e spectrum of Christian theology, social stances, and the CJ public behavior. The worldview represented by the 25 big denominations is identical to the Christ worldview held by the additional 900+ Christian denominations in America, which together who f include between 70 and 80 percent of the American population. -

Caring for the Elderly 1984: Curiouser and Curiouser the Doggett

TEXAS 13 ERVER A Journal of Free Voices August 31, 1984 $1.00 The Doggett A Campaign (page 2) _. I:IT iitle7■—ffft,i 41.1 .t . 11111.4, 1 iliallgallit 111111111111111 If II Vilifignifill ;f1111'1111111111111.1111i ilia/ .Z..S 1141 011' : • .,.. .1., . - • ,:-... I "Ir • • ,...p '#11/ ' let i 0 . iglu/rim! 'I tffi 1 . i,1 I ■44.1446 ., .:: . a) --,,t- ci) 0 a_ • — , tiggEllr.":1:141 "..;:7—*" ... 0 —J r_ls.t.....iOis... L. .0 ti) 0 0 0 (0 CI— C Caring for 0 the Elderly 1984: Curiouser (page 5) and Curiouser (page 17) - == --7-------. -== --7'.--- - - • fs FOE ,,, PAGE TWO — 0 _ Trig PEOPz — tP c---. dir HI PR I El`IS' — _.=_. • la _ ,4J Doggett Campaign ••■■ . - --_,-,..- -..... --- , , , _ , io , ----- ,......_ __ it , 11,1.'11111mo' ,,1, 0 1, iiii ii,. I .. I II III 11E10 it 1 il _____ I! N111111101 10'1'111 ' 1 ' ,,........_ in High Gear Gm --z..-=--------- • TETXDB SERvER Austin ETWEEN NOW and November 6, the crucial equation „(,, The Texas Observer Publishing Co.. 1984 for state Senator Lloyd Doggett to solve involves the Ronnie Dugger, Publisher B amount of money that must be raised to add to his base of support from the Democratic primary in order to pull Vol. 76, No. 17 7 .1: , .' -7 August 31, 1984 enough votes from the yet uncommitted to defeat Phil Gramm Incorporating the State Observer and the East Texas Democrat, in the general election. In a state with wide expanses to traverse which in turn incorporated the Austin Forum-Advocate. and more than a dozen major television markets, television EDITOR Geoffrey Rips air-time becomes the determining factor in a close election. -

Quartet March2020

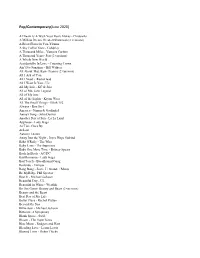

Pop/Contemporary (June 2020) A Dream Is A Wish Your Heart Makes - Cinderella A Million Dream Greatest Showman (2 versions) A River Flows in You-Yiruma A Sky Full of Stars - Coldplay A Thousand Miles - Vanessa Carlton A Thousand Years- Peri (2 versions) A Whole New World Accidentally In Love - Counting Crows Ain't No Sunshine - Bill Withers All About That Bass- Trainor (2 versions) All I Ask of You All I Need - RadioHead All I Want Is You - U2 All My Life - KC & Jojo All of Me- John Legend All of My love All of the Lights - Kayne West All The Small Things - Blink 182 Always - Bon Jovi America - Simon & Garfunkel Annie's Song - John Denver Another Day of Sun - La La Land Applause - Lady Gaga As Time Goes By At Last Autumn Leaves Away Into the Night - Joyce Hope Siskind Baba O'Reily - The Who Baby Love - The Supremes Baby One More Time - Britney Spears Back In Black - AC/DC Bad Romance - Lady Gaga Bad Touch - Bloodhound Gang Bailando - Enrique Bang Bang - Jessie J / Grande / Minaj Be MyBaby- Phil Spector Beat It - Michael Jackson Beautiful Day - U2 Beautiful in White - Westlife Be Our Guest- Beauty and Beast (2 versions) Beauty and the Beast Best Day of My Life Better Place - Rachel Platten Beyond the Sea Billie Jean - Michael Jackson Bittersweet Symphony Blank Space - Swift Bloom - The Paper Kites Blue Moon - Rodgers and Hart Bleeding Love - Leona Lewis Blurred Lines - Robin Thicke Bohemian Rapsody-Queen Book of Days - Enya Book of Love - Peter Gabriel Boom Clap - Charli XCX Brown Eyed Girl - Van Morrison Budapest - Geo Ezra Buddy Holly- -

Congressman Jack Brooks- "Taking Care of Business"

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 51 Issue 2 Article 7 3-2013 Congressman Jack Brooks- "Taking Care of Business" Robert J. Robertson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Robertson, Robert J. (2013) "Congressman Jack Brooks- "Taking Care of Business"," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 51 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol51/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONGRESSMAN JACK BROOKS - "TAKING CARE OF BUSINESS" Robert J. Robertson On the afternoon of August 21, 1970, Congressman Jack Brooks and his wife Charlotte traveled to -Port Arthur, Texas, to participate in the grand opening ofthe new $8.8 million Gulfgate Bridge over the Sabine Neches ship channel. Completion of the bridge marked the culmination of a large maritime transportation project sponsored by Brooks in 1962, when he won a $20.8 million Federal appropriation for various improvements for the Sabine-Neches Waterway that ran from the Gulf of Mexico up to Beaumont. The waterway improvements and new bridge were critical for the industrial development ofthe Beaumont-Port Arthur region, where Brooks resided and which formed the heart of his congressional d istrict.1 Staged near the west entrance of the towering new bridge, the dedication ceremonies began at 5:30 PM with posting of the colors by the U. -

Chicagská Škola – Interdisciplinární Dědictví Moderního Výzkumu Velkoměsta

Univerzita Karlova v Praze Filozofická fakulta Katedra teorie kultury (kulturologie) Obecná teorie a dějiny umění a kultury Tobiáš Petruželka Chicagská škola – interdisciplinární dědictví moderního výzkumu velkoměsta Chicago School – The Interdisciplinary Heritage of the Modern Urban Research Disertační práce Vedoucí práce – PhDr. Miloslav Lapka, CSc. 2014 1 „Prohlašuji, že jsem disertační práci napsal samostatně s využitím pouze uvedených a řádně citovaných pramenů a literatury a že práce nebyla využita v rámci jiného vysokoškolského studia či k získání jiného nebo stejného titulu.“ V Helsinkách 25. 3. 2014 Tobiáš Petruželka 2 Poděkování Poděkování patří především vedoucímu práce dr. Miloslavu Lapkovi, který, ač převzal vedení práce teprve před rokem a půl, se rychle seznámil s tématem i materiálem a poskytl autorovi práce potřebnou podporu. Poděkování patří i dr. Jitce Ortové, která se vedení této disertace i doktorského studia s péčí věnovala až do skončení svých akademických aktivit. Díky také všem, kteří text v různých fázích četli a komentovali. Helsinské univerzitní knihovně je třeba vyslovit dík za systematické a odborné akvizice a velkorysé výpůjční lhůty. Abstrak t Cílem disertace je interdisciplinární kontextualizace chicagské sociologické školy, zaměřuje se především na ty její aspekty, jež se týkají sociologických výzkumů města Chicaga v letech 1915–1940. Cílem práce je propojit historický kontext a lokální specifika tehdejších výzkumů s výzkumným programem chicagské školy a jeho naplňováním. Nejprve jsou přiblíženy vybrané výzkumy, které chicagskou školy předcházely, dále jsou představena konceptuální a teoretická východiska jejího výzkumného programu. Nakonec jsou v tématických kapitolách kriticky prozkoumány nejvýznamnější monografie chicagské školy z let 1915–1940. Disertace se zabývá především tématy moderní urbánní kultury, migrace, kriminality a vývojem sociálního výzkumu v městském prostředí. -

TNT Greenlights New Series DALLAS

TNT Greenlights New Series DALLAS TNT has given the greenlight to DALLAS, an all-new series based upon one of the most popular television dramas of all time, about the bitter rivalries and family power struggles within a Texas oil and cattle-ranching dynasty. Famous for its ratings-grabbing cliffhangers, the original series was known for its wealth, seduction, scandal and intrigues. Set in the big state of Texas, TNT’s new DALLAS — from Warner Horizon Television — also lives life large and in the fast lane and brings a new generation of stars together with cast members from the original drama series. The new DALLAS stars Josh Henderson (90210), Jesse Metcalfe (John Tucker Must Die), Jordana Brewster (Fast & Furious), Julie Gonzalo (Veronica Mars) and Brenda Strong (Desperate Housewives), and they will be joined by iconic stars Patrick Duffy, Linda Gray and Larry Hagman as J.R. Ewing. TNT has ordered 10 episodes of DALLAS, which is slated to premiere in summer 2012. TNT will give viewers their first look at DALLAS on Monday with a special sneak peek during the season premieres of the network’s blockbuster hits THE CLOSER, which starts at 9 p.m. (ET/PT), and RIZZOLI & ISLES, which airs at 10 p.m. (ET/PT). TNT is unveiling today a website dedicated to the new DALLAS series, where fans can view an online photo gallery that features a first look into the show’s new and returning cast. Fans can visit the new site, http://www.dallastnt.com, to watch sneak peeks and behind-the-scenes videos. -

Crowning the Queen of the Sonoran Desert: Tucson and Saguaro National Park

Crowning the Queen of the Sonoran Desert: Tucson and Saguaro National Park An Administrative History Marcus Burtner University of Arizona 2011 Figure 1. Copper Pamphlet produced by Tucson Chamber of Commerce, SAGU257, Box 1, Folder 11, WACC. “In a canon near the deserted mission of Cocospera, Cereus giganteus was first met with. The first specimen brought the whole party to a halt. Standing alone upon a rocky projection, it rose in a single unbranched column to the height of some thirty feet, and formed a sight which seemed almost worth the journey to behold. Advancing into the canon, specimens became more numerous, until at length the whole vegetation was, in places, made up of this and other Cacaceae. Description can convey no adequate idea of this singular vegetation, at once so grand and dreary. The Opuntia arborescens and Cereus Thurberi, which had before been regarded with wonder, now seemed insignificant in comparison with the giant Cactus which towered far above.” George Thurber, 1855, Boundary Commission Report.1 Table of Contents 1 Asa Gray, ―Plantae Novae Thurberianae: The Characters of Some New Genera and Species of Plants in a Collection Made by George Thurber, Esq., of the Late Mexican Boundary ii List of Illustrations v List of Maps ix Introduction Crowning the Queen of the Desert 1 The Question of Social Value and Intrinsically Valuable Landscapes Two Districts with a Shared History Chapter 1 Uncertain Pathways to a Saguaro National Monument, 1912-1933 9 Saguaros and the Sonoran Desert A Forest of Saguaros Discovering