Congressman Jack Brooks- "Taking Care of Business"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers Asian Native Asian Native Am. Black Hisp Am. Total Am. Black Hisp Am. Total ALABAMA The Anniston Star........................................................3.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 6.1 Free Lance, Hollister ...................................................0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 12.5 The News-Courier, Athens...........................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Lake County Record-Bee, Lakeport...............................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Birmingham News................................................0.7 16.7 0.7 0.0 18.1 The Lompoc Record..................................................20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 The Decatur Daily........................................................0.0 8.6 0.0 0.0 8.6 Press-Telegram, Long Beach .......................................7.0 4.2 16.9 0.0 28.2 Dothan Eagle..............................................................0.0 4.3 0.0 0.0 4.3 Los Angeles Times......................................................8.5 3.4 6.4 0.2 18.6 Enterprise Ledger........................................................0.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Madera Tribune...........................................................0.0 0.0 37.5 0.0 37.5 TimesDaily, Florence...................................................0.0 3.4 0.0 0.0 3.4 Appeal-Democrat, Marysville.......................................4.2 0.0 8.3 0.0 12.5 The Gadsden Times.....................................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Merced Sun-Star.........................................................5.0 -

Community Involvement Plan April 2003

Star Lake Canal Superfund Site Jefferson County, Texas Community Involvement Plan April 2003 U. S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY REGION 6 002674 CONTENTS Section Page 1 Introduction .......................................................... 1 2 Site Background and Status .............................................. 3 Site Description and History ....................................... 3 National Priorities List ........................................... 4 Enforcement Program Activities .................................... 4 Current and Upcoming Site Activities ............................... 5 Site Map ...................................................... 6 3 Community Involvement Background ..................................... 7 Community Profile .............................................. 7 Community Issues, Concerns, and Information Needs .............................................. 7 4 Community Involvement Program ........................................ 9 Community Involvement Objectives ................................. 9 Community Involvement Activities and Tools ......................... 9 Community Involvement Program Schedule ......................... 13 Appendices A Superfund Glossary ................................................... 14 B Community Involvement Plan Interview Questionnaire ....................... 16 C Contact List......................................................... 17 D Community Involvement Program Schedule ................................ 21 Star Lake Canal Site Community Involvement Plan -

Caring for the Elderly 1984: Curiouser and Curiouser the Doggett

TEXAS 13 ERVER A Journal of Free Voices August 31, 1984 $1.00 The Doggett A Campaign (page 2) _. I:IT iitle7■—ffft,i 41.1 .t . 11111.4, 1 iliallgallit 111111111111111 If II Vilifignifill ;f1111'1111111111111.1111i ilia/ .Z..S 1141 011' : • .,.. .1., . - • ,:-... I "Ir • • ,...p '#11/ ' let i 0 . iglu/rim! 'I tffi 1 . i,1 I ■44.1446 ., .:: . a) --,,t- ci) 0 a_ • — , tiggEllr.":1:141 "..;:7—*" ... 0 —J r_ls.t.....iOis... L. .0 ti) 0 0 0 (0 CI— C Caring for 0 the Elderly 1984: Curiouser (page 5) and Curiouser (page 17) - == --7-------. -== --7'.--- - - • fs FOE ,,, PAGE TWO — 0 _ Trig PEOPz — tP c---. dir HI PR I El`IS' — _.=_. • la _ ,4J Doggett Campaign ••■■ . - --_,-,..- -..... --- , , , _ , io , ----- ,......_ __ it , 11,1.'11111mo' ,,1, 0 1, iiii ii,. I .. I II III 11E10 it 1 il _____ I! N111111101 10'1'111 ' 1 ' ,,........_ in High Gear Gm --z..-=--------- • TETXDB SERvER Austin ETWEEN NOW and November 6, the crucial equation „(,, The Texas Observer Publishing Co.. 1984 for state Senator Lloyd Doggett to solve involves the Ronnie Dugger, Publisher B amount of money that must be raised to add to his base of support from the Democratic primary in order to pull Vol. 76, No. 17 7 .1: , .' -7 August 31, 1984 enough votes from the yet uncommitted to defeat Phil Gramm Incorporating the State Observer and the East Texas Democrat, in the general election. In a state with wide expanses to traverse which in turn incorporated the Austin Forum-Advocate. and more than a dozen major television markets, television EDITOR Geoffrey Rips air-time becomes the determining factor in a close election. -

Minority Percentages at Participating News Organizations

Minority Percentages at Participating News Organizations Asian Native Asian Native American Black Hispanic American Total American Black Hispanic American Total ALABAMA Paragould Daily Press 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Anniston Star 0.0 7.7 0.0 0.0 7.7 Pine Bluff Commercial 0.0 13.3 0.0 0.0 13.3 The Birmingham News 0.8 18.3 0.0 0.0 19.2 The Courier, Russellville 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Decatur Daily 0.0 7.1 3.6 0.0 10.7 Northwest Arkansas Newspapers LLC, Springdale 0.0 1.5 1.5 0.0 3.0 Enterprise Ledger 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Stuttgart Daily Leader 0.0 0.0 20.0 0.0 20.0 TimesDaily, Florence 0.0 2.9 0.0 0.0 2.9 Evening Times, West Memphis 0.0 25.0 0.0 0.0 25.0 The Gadsden Times 0.0 5.6 0.0 0.0 5.6 CALIFORNIA The Daily Mountain Eagle, Jasper 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Desert Dispatch, Barstow 14.3 0.0 0.0 0.0 14.3 Valley Times-News, Lanett 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Center for Investigative Reporting, Berkeley 7.1 14.3 14.3 0.0 35.7 Press-Register, Mobile 0.0 10.5 0.0 0.0 10.5 Ventura County Star, Camarillo 1.6 3.3 16.4 0.0 21.3 Montgomery Advertiser 0.0 19.5 2.4 0.0 22.0 Chico Enterprise-Record 3.6 0.0 0.0 0.0 3.6 The Daily Sentinel, Scottsboro 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Daily Triplicate, Crescent City 11.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 11.1 The Tuscaloosa News 5.1 2.6 0.0 0.0 7.7 The Davis Enterprise 7.1 0.0 7.1 0.0 14.3 ALASKA Imperial Valley Press, El Centro 17.6 0.0 41.2 0.0 58.8 Fairbanks Daily News-Miner 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 North County Times, Escondido 1.3 0.0 5.2 0.0 6.5 Peninsula Clarion, Kenai 0.0 10.0 0.0 0.0 10.0 The Fresno Bee 6.4 1.3 16.7 0.0 24.4 The Daily News, Ketchikan -

Panel 3: the Money Can Online Journalism Become a Profitable Business? When and How? Where Are the Success Stories? Where Is

2002 – International Symposium on Online Journalism Panel 3: The Money Can online journalism become a profitable business? When and how? Where are the success stories? Where is revenue going? Is paid access a feasible model for online news sites? Does online advertising on news sites work? What is the outlook for ad-driven sites? Moderator: Neal M. Burns, Professor, Department of Advertising, UT Austin Panelists: Eric A. Christensen, Vice President and General Manager, Belo Interactive Ken Riddick, Director of Interactive Media, Fresno Bee Larry K. Sanders, General Manager, statesman.com, former Vice President and General Manager, Usatoday.com Julie Weber, Digital Media Manager, Hearst Newspapers NEAL BURNS: …..Larry Sanders and then Julie Weber. In the novel treatment of gender, we have elected to let our female companion first and colleague to last. I've also been advised that sitting up here is not a cool thing to do. And so I'm going to vacate. The floor is yours. ….the article on web loggers. Did anybody read that besides me? What did you think about that article? Can anyone offer a comment about that? By the way, I wasn't here during the morning. Was it discussed? [No.] Let me just give you my short summary as I recall and then someone who's read it can say.. The issue is whether I say anything. The article describes, by the way, and it contrasts the New York Times, the Washington Post, the traditional kind of journalism. It suggests essentially an archaic architecture. And contrasted to what in a sense is the current architecture, that essentially based in large part a P to P model. -

09-05-12, No. 10

Beaumont Page 1 of 6 Tue Sep 04, 2012 Home Speakers ROTARYGRAMS Sep 05, 2012 September 5, 2012 - Vol. 100, No. 10 Dr. Timothy Chargois State of BISD MCM Elegante' Hotel Sep 05, 2012 2355 IH-10 South [ROTARIAN OF THE DAY: Suite 213 Mayor Becky Ames] Texas Capitol Vietnam Veterans Beaumont, TX 77705 Monument Sep 12, 2012 Telephone: 409-842-1913 Joseph Mayer, Lockhead Martin Fax: 409-842-5613 Future of Space Travel Sep 19, 2012 Robert Keith Horry, Jr., Retired NBA Great & ESPN DON'T MISS A MINUTE Sports Commentator on relating The bell will ring at 12:15 this Wednesday to allow plenty of time for all of athletic skills to job skills our agenda items including Rotarian of the Day Mayor Becky Ames, a Sep 26, 2012 program presented by the new BISD Superintendent Timothy Chargois Brett Bertles, Sharon & PDG and early dismissal. The Chamber of Commerce is hosting an Roger McCabe informational meeting with American Airlines at 1:15 to discuss bringing Our Trip to Nicaragua air service back to our community. Early dismissal of the club will make it possible for interested members to attend both the Rotary meeting and Oct 03, 2012 the Chamber meeting. Debbie Reynolds, Texas Wine & Grape Growers Assn. "Texas Wine, Excellence Uncorked" Oct 10, 2012 TBA - Meeting will be in the Fountainview Room PROGRAM PREVIEW September 5, 2012 Oct 17, 2012 Vocational Awareness Awards Jane Burns, Chairman "The State of BISD" Oct 24, 2012 Ruth Ann Rugg, Texas Association of Museums The Value of Museums to the Local Community View entire list.. -

Amended by Adding Section 418.054 to Read As Follows: Sec.I418.054.Iidisaster RECOVERY TASK FORCE

HOUSE JOURNAL EIGHTY-SIXTH LEGISLATURE, REGULAR SESSION PROCEEDINGS SEVENTIETH DAY Ð TUESDAY, MAY 21, 2019 The house met at 10:17 a.m. and was called to order by the speaker. The roll of the house was called and a quorum was announced present (Recordi1529). Present Ð Mr. Speaker(C); Allen; Allison; Anchia; Anderson; Ashby; Bailes; Beckley; Bell, C.; Bell, K.; Bernal; Biedermann; Blanco; Bohac; Bonnen; Bowers; Buckley; Bucy; Burns; Burrows; Button; Cain; Calanni; Canales; Capriglione; Clardy; Cole; Coleman; Collier; Cortez; Craddick; Cyrier; Darby; Davis, S.; Davis, Y.; Dean; Deshotel; Dominguez; Dutton; Farrar; Fierro; Flynn; Frank; Frullo; Geren; Gervin-Hawkins; Goldman; GonzaÂlez, J.; GonzaÂlez, M.; Goodwin; Guerra; Guillen; Gutierrez; Harless; Harris; Hefner; Hernandez; Herrero; Hinojosa; Holland; Howard; Huberty; Hunter; Israel; Johnson, J.D.; Johnson, J.E.; Kacal; King, K.; King, P.; King, T.; Klick; Krause; Kuempel; Lambert; Landgraf; Lang; Larson; Leach; Leman; Longoria; Lopez; Lozano; Lucio; Martinez; Martinez Fischer; Metcalf; Meyer; Meza; Middleton; Miller; Minjarez; Moody; Morales; Morrison; MunÄoz; Murphy; Murr; Neave; NevaÂrez; Noble; Oliverson; Ortega; Pacheco; Paddie; Parker; Patterson; Paul; Perez; Phelan; Price; Ramos; Raney; Raymond; Reynolds; Rodriguez; Romero; Rose; Rosenthal; Sanford; Schaefer; Shaheen; Sheffield; Sherman; Shine; Smith; Smithee; Springer; Stephenson; Stickland; Stucky; Swanson; Talarico; Thierry; Thompson, E.; Thompson, S.; Tinderholt; Toth; Turner, C.; Turner, J.; VanDeaver; Vo; Walle; White; Wilson; Wray; Wu; Zedler; Zerwas; Zwiener. Absent, Excused Ð Johnson, E. The invocation was offered by Marc R. Farnell Jr., senior pastor, CrossRidge Church, Little Elm, as follows: Our almighty God and gracious heavenly Father, we thank you for today. We thank you for all our many blessings. We thank you for how you have blessed our nation and our great state for so many years. -

Cardinal Cadence for Web 6/04

CadenceCARDINAL From the President The Staff Whether the focus is on construction or instruction, summertime Cardinal Cadence is published by the Division of at Lamar University is a time of preparation for the approaching University Advancement, Lamar University, a member of The Texas State University System and an affirmative academic year. These months, you can find some Lamar faculty action, equal opportunity educational institution. teaching summer courses, while others are engaged in scholarly Brian Sattler, Executive Editor, Director of Public Relations Cynthia Hicks ’89, ’93, Editor activities, research or travel. Louise Wood, Writer The sounds of construction continue from the west side of Chris Castillo, Writer campus as the third phase of Cardinal Village nears completion. When the state-of- Contributors: Daucy Crizer, Amanda Rowell, writing the-art facility opens in August, it will bring Lamar’s residence hall capacity to 1,500 Allen Moore, Rohn Wenner, photography Cardinal Events 2004 students. The new 25,000-square-foot dining hall will follow in the construction Circulation includes 54,000 copies distributed to alumni, July 28-29 Sept. 13 faculty, staff and friends of Lamar University. If you have Orientation. (409) 880-8085 Nationally syndicated colum- schedule. Particularly exciting is the prospect of the renovation of McDonald Gym nist Leonard Pitts, 7 p.m. received more than one copy of this publication, please Aug. 10-11 let us know. University Theatre. Hosted by into a comprehensive fitness facility that is sure to become a center of activity for Orientation. (409) 880-8085 the College of Fine Arts and Changes of address may be sent to: Aug. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents About TPA ............................................................................................................................................... 2 Member Services..................................................................................................................................... 2 Board of Directors.................................................................................................................................... 4 TPA Staff ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Newspapers (sorted by city) .................................................................................................................... 6 Directory Cover Contest Finalists ......................................................................................................... 81 Texas Group Newspapers by Ownership .............................................................................................. 83 Newspapers by County ......................................................................................................................... 85 Map of Texas Counties.......................................................................................................................... 85 Associate Members ............................................................................................................................... 89 Texas Newspaper Foundation Hall of Fame Members ........................................................................ -

Settlement Agreement

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA IN RE: TOYOTA MOTOR CORP. Case No. 8:10ML2151 JVS (FMOx) UNINTENDED ACCELERATION MARKETING, SALES PRACTICES, AND PRODUCTS LIABILITY LITIGATION This Document Relates to: ALL ECONOMIC LOSS ACTIONS SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page I. DEFINITIONS ....................................................................................................... 3 II. SETTLEMENT RELIEF ..................................................................................... 11 III. NOTICE TO THE CLASS .................................................................................. 19 IV. REQUESTS FOR EXCLUSION ......................................................................... 25 V. OBJECTIONS TO SETTLEMENT .................................................................... 26 VI. RELEASE AND WAIVER ................................................................................. 28 VII. ATTORNEYS’ FEES AND EXPENSES AND INDIVIDUAL PLAINTIFF AND CLASS REPRESENTATIVE AWARDS ........................................................... 32 VIII. PRELIMINARY APPROVAL ORDER, FINAL ORDER, FINAL JUDGMENT AND RELATED ORDERS ................................................................................. 35 IX. MODIFICATION OR TERMINATION OF THIS AGREEMENT ................... 37 X. GENERAL MATTERS AND RESERVATIONS ............................................... 40 i TABLE OF EXHIBITS Document Exhibit Number List of Economic Loss Actions in the MDL ..........................................................................1 -

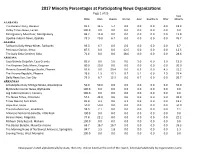

2017 Summary Report for Each News Organization.Xlsx

2017 Minority Percentages at Participating News Organizations Page 1 of 25 Total White Black Hispanic Am. Ind. Asian Haw/Pac. Is Other Minority ALABAMA The Decatur Daily, Decatur 81.1 13.5 5.4 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 18.9 Valley Times-News, Lanett 100.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Montgomery Advertiser, Montgomery 84.2 15.8 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 15.8 Opelika-Auburn News, Opelika 73.3 20.0 6.7 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 26.7 ALASKA Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, Fairbanks 93.3 6.7 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 6.7 Peninsula Clarion, Kenai 87.5 0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 0.0 0.0 12.5 The Daily Sitka Sentinel, Sitka 71.4 0.0 0.0 28.6 0.0 0.0 0.0 28.6 ARIZONA Casa Grande Dispatch, Casa Grande 85.0 0.0 5.0 0.0 5.0 0.0 5.0 15.0 The Kingman Daily Miner, Kingman 80.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Phoenix Gannett Design Studio, Phoenix 65.6 0.0 20.4 0.0 6.5 0.0 4.3 31.2 The Arizona Republic, Phoenix 76.6 1.5 13.1 0.7 5.1 0.0 2.9 23.4 Daily News-Sun, Sun City 73.3 6.7 13.3 0.0 6.7 0.0 0.0 26.7 ARKANSAS Arkadelphia Daily Siftings Herald, Arkadelphia 50.0 50.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 50.0 Blytheville Courier News, Blytheville 100.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Log Cabin Democrat, Conway 100.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The News-Times, El Dorado 57.1 42.9 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 42.9 Times Record, Fort Smith 81.8 9.1 0.0 9.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 18.2 Hope Star, Hope 50.0 50.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 50.0 The Jonesboro Sun, Jonesboro 92.9 7.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 7.1 Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Little Rock 100.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Banner-News, Magnolia 77.8 22.2 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 22.2 Malvern Daily Record, Malvern 100.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Baxter Bulletin, Mountain Home 66.7 16.7 16.7 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 33.3 The Morning News of Northwest Arkansas, Springdale 94.7 3.5 1.8 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 5.3 Evening Times, West Memphis 100.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Newspapers listed alphabetically by state, then city. -

State of Louisiana Court of Appeal, Third Circuit 08-522

STATE OF LOUISIANA COURT OF APPEAL, THIRD CIRCUIT 08-522 THE CHICAGO TRIBUNE COMPANY, ET AL. VERSUS HONORABLE J. P. MAUFFRAY, JR., ET AL. ********** APPEAL FROM THE TWENTY-EIGHTH JUDICIAL DISTRICT COURT PARISH OF LASALLE, NO. 35,858 HONORABLE THOMAS MARTIN YEAGER, JUDGE AD HOC ********** JOHN D. SAUNDERS JUDGE ********** Court composed of John D. Saunders, James T. Genovese, and Chris J. Roy, Sr.*, Judges. REVERSED AND REMANDED. Dan Brian Zimmerman Mary Ellen Roy Phelps Dunbar, L.L.P. 365 Canal St., Ste 2000 New Orleans, LA 70130-6534 Counsel for Plaintiff/Appellee: The Chicago Tribune Company, et al. *Honorable Chris J. Roy, Sr., participated in this decision by appointment of the Louisiana Supreme Court as Judge Pro Tempore. Donald R. Wilson Gaharan & Wilson P. O. Box 1346 Jena, LA 71342 (318) 992-2104 Counsel for Defendants/Appellants: Honorable John Philip Mauffray, Jr. Steve H. Crooks, Clerk James D. Caldwell Attorney General David G. Sanders Patricia Hill Wilton Assistants Attorney General P. O. Box 94005 Baton Rouge, LA 70804-9005 (225) 326-6300 Counsel for Defendants/Appellants: Honorable John Philip Mauffray, Jr. Steve H. Crooks, Clerk SAUNDERS, Judge. FACTS AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY: This appeal arises from a writ of mandamus issued in the 28th Judicial District Court by the Honorable Thomas M. Yeager (hereinafter Judge Yeager), who was appointed by the Louisiana Supreme Court to preside ad hoc over a writ application filed in that district by Appellees (hereinafter “News Media”).** The News Media’s writ application sought to compel the Honorable J.P. Mauffray, Jr. (hereinafter Judge Mauffray), Judge for the 28th Judicial District Court, to open to the public the proceedings in State of Louisiana in the Interest of Mychal Bell, juvenile case number J-4002.