Psalm 119 2860 : 355 = 8.05

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wallace Berman Aleph

“Art is Love is God”: Wallace Berman and the Transmission of Aleph, 1956-66 by Chelsea Ryanne Behle B.A. Art History, Emphasis in Public Art and Architecture University of San Diego, 2006 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURE STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2012 ©2012 Chelsea Ryanne Behle. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: __________________________________________________ Department of Architecture May 24, 2012 Certified by: __________________________________________________________ Caroline Jones, PhD Professor of the History of Art Thesis Supervisor Accepted by:__________________________________________________________ Takehiko Nagakura Associate Professor of Design and Computation Chair of the Department Committee on Graduate Students Thesis Supervisor: Caroline Jones, PhD Title: Professor of the History of Art Thesis Reader 1: Kristel Smentek, PhD Title: Class of 1958 Career Development Assistant Professor of the History of Art Thesis Reader 2: Rebecca Sheehan, PhD Title: College Fellow in Visual and Environmental Studies, Harvard University 2 “Art is Love is God”: Wallace Berman and the Transmission of Aleph, 1956-66 by Chelsea Ryanne Behle Submitted to the Department of Architecture on May 24, 2012 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies ABSTRACT In 1956 in Los Angeles, California, Wallace Berman, a Beat assemblage artist, poet and founder of Semina magazine, began to make a film. -

Psalms 119 & the Hebrew Aleph

Psalms 119 & the Hebrew Aleph Bet - Part 17 The seventeenth letter of the Hebrew alphabet is called “Pey” (sounds like “pay”). It has the sound of “p” as in “park”. Pey has the numeric value of 80. In modern Hebrew, the letter Pey can appear in three forms: Writing the Letter: Pey Note: Most people draw the Pey in two strokes, as shown. The dot, or “dagesh” mark means the pey makes the “p” sound, as in “park”. Note: The sole difference between the letter Pey and the letter Fey is the presence or absence of the dot in the middle of the letter (called a dagesh mark). When you see the dot in the middle of this letter, pronounce it as a "p"; otherwise, pronounce it as "ph" (or “f”). Five Hebrew letters are formed differently when they appear as the last letter of a word (these forms are sometimes called "sofit" (pronounced "so-feet") forms). Fortunately, the five letters sound the same as their non-sofit cousins, so you do not have to learn any new sounds (or transliterations). The Pey (pronounced “Fey” sofit has a descending tail, as shown on the left. Pey: The Mouth, or Word The pictograph for Pey looks something like a mouth, whereas the classical Hebrew script (Ketav Ashurit) is constructed of a Kaf with an ascending Yod: Notice the “hidden Bet” within the letter Pey. This shape of the letter is required when a Torah scribe writes Torah scrolls, or mezzuzahs. From the Canaanite pictograph, the letter morphed into the Phoenician ketav Ivri, to the Greek letter (Pi), which became the Latin letter “P.” means “mouth” and by extension, “word,” “expression,” “vocalization,” and “speech”. -

The Sign of the Cross

The Sign of the Cross ἰχθύς – fish – acrostic: Ίησοῦς Χριστός, Θεοῦ Υἱός, Σωτήρ (Jesus Christ, Son of God, Savior) From early EPhesus: From the catacomb os St. Sebastian (martyed c 288): Hebrew tav: Cursive (scriPt) Hebrew: For Jews, who may not say or write God’s name, the letter taw was used as a rePresentation of God’s name. It’s the last letter in the Hebrew alPhabet and synbolizes the end, comPletion, and Perfection. Note the similarity to the Greek letter chi (first letter in the Greek Christ (Χριστός) Some early icons (note the mark of the cross on the forehead): 1 A “mark” is sometimes a negative thing in the Old Testament. Cain is “marked” (see Genesis 4:15) “So the LORD Put a mark on Cain, so that no one would kill him at sight.” A sore on the forehead could mark a Person as unclean. See Leviticus ChaPter 14. Note our discussion on Ezekiel. In the New Testament: Revelation 14:1: Then I looked and there was the Lamb standing on Mount Zion, and with him a hundred and forty-four thousand who had his name and his Father’s name written on their foreheads. Revelation 22:4 - They will look upon his face, and his name will be on their foreheads. St. Cyril of Jerusalem (fourth century) “Let us then not be ashamed to confess to Crucified. Let the cross as a seal, be boldly made with our fingers uPon our brow and on all occasions; over the bread we eat, over the cuPs and drink, in our comings and goings, before sleeP, on lying down and rising uP, when we are on our way and when we are still. -

MULTI-SENSORY ALEPH BET Submitted by Janine Starr Project Title

MULTI-SENSORY ALEPH BET Submitted by Janine Starr Project Title: Multi-sensory Aleph Bet Subject Area: The shapes and sounds of the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet Target Age Group(s): 2nd grade Lesson Objective(s): Students will integrate the shape and sound of each letter deeply to support future fluency in Hebrew reading. This is a program that I designed and implemented for a class of second graders in the JCRB Beit Sefer Chadash, 2002-2003, under the directorship of Rabbi Nadya Gross. Each week of school we studied one or two letters and its (their) sound(s) in a variety of ways. THE BEST ORDER IN WHICH TO TEACH THE LETTERS IS THAT FOLLOWED BY THE TEXT BOOK SAM THE DETECTIVE published by KTAV. Copyright © 2004, Weaver Family Foundation. www.WeaverFoundation.org Page 1 of 6 MULTI-SENSORY ALEPH BET Submitted by Janine Starr LEVEL I First, we studied the letter visually. I held up a poster board with the outline of the letter drawn large, the gamatria number, and a Hebrew word written in English letters that began with the letter, and that summarized it’s essence (i.e., for beit, I used the word Bayit, meaning house, because bet looks like a house, and it’s spiritual meaning, or “essence” is also “house”.) The children used their fingers to trace a large letter shape in the air, using the poster for guidance. LEVEL II Next, I added the auditory level. I told a story to teach the essence of the letter, and help the children remember the “essence” and special word that went along with the letter. -

The Christological Aspects of Hebrew Ideograms Kristološki Vidiki Hebrejskih Ideogramov

1027 Pregledni znanstveni članek/Article (1.02) Bogoslovni vestnik/Theological Quarterly 79 (2019) 4, 1027—1038 Besedilo prejeto/Received:09/2019; sprejeto/Accepted:10/2019 UDK/UDC: 811.411.16'02 DOI: https://doi.org/10.34291/BV2019/04/Petrovic Predrag Petrović The Christological Aspects of Hebrew Ideograms Kristološki vidiki hebrejskih ideogramov Abstract: The linguistic form of the Hebrew Old Testament retained its ancient ideo- gram values included in the mystical directions and meanings originating from the divine way of addressing people. As such, the Old Hebrew alphabet has remained a true lexical treasure of the God-established mysteries of the ecclesiological way of existence. The ideographic meanings of the Old Hebrew language represent the form of a mystagogy through which God spoke to the Old Testament fathers about the mysteries of the divine creation, maintenance, and future re-creation of the world. Thus, the importance of the ideogram is reflected not only in the recognition of the Christological elements embedded in the very structure of the Old Testament narrative, but also in the ever-present working structure of the existence of the world initiated by the divine economy of salvation. In this way both the Old Testament and the New Testament Israelites testify to the historici- zing character of the divine will by which the world was created and by which God in an ecclesiological way is changing and re-creating the world. Keywords: Old Testament, old Hebrew language, ideograms, mystagogy, Word of God, God (the Father), Holy Spirit, Christology, ecclesiology, Gospel, Revelation Povzetek: Jezikovna oblika hebrejske Stare Zaveze je obdržala svoje starodavne ideogramske vrednote, vključene v mistagoške smeri in pomene, nastale iz božjega načina nagovarjanja ljudi. -

Prevalence and Risk Factors of Anxiety and Depression Among The

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Prevalence and risk factors of anxiety and depression among the community‑dwelling elderly in Nay Pyi Taw Union Territory, Myanmar Su Myat Cho1, Yu Mon Saw1,2*, Thu Nandar Saw3, Thet Mon Than4, Moe Khaing4, Aye Thazin Khine5, Tetsuyoshi Kariya1,2, Pa Pa Soe6, San Oo7 & Nobuyuki Hamajima1 Providing elderly mental healthcare in Myanmar is challenging due to the growing elderly population and limited health resources. To understand common mental health problems among Myanmar elderly, this study explored the prevalence and risk factors of anxiety and depression among the elderly in the Nay Pyi Taw Union Territory, Myanmar. A cross‑sectional study was conducted among 655 elderly by face‑to‑face interviews with a pretested questionnaire. Descriptive analysis and multiple logistic regression analyses were performed. The prevalence of anxiety and depression were 39.4% (33.5% for males and 42.4% for females) and 35.6% (33.0% for males and 36.9% for females), respectively. The adjusted odds ratio of having anxiety was signifcant for having low education level, having comorbidity, having BMI < 21.3, poor dental health, no social participation, and having no one to consult regarding personal problems, while that of having depression was signifcant for having comorbidity, having BMI < 21.3, poor vision, and having no one to consult regarding personal problems. The reported prevalence of anxiety and depression indicate the demand for mental healthcare services among Myanmar elderly. Myanmar needs to improve its elderly care, mental healthcare, and social security system to refect the actual needs of its increasing elderly population. -

Introduction to Using Hebrew Language Tools Syllabus Institute

Introduction to Using Hebrew Language Tools Syllabus 15 March to 10 May 2016 Whitney Oxford Institute of Grace Grace Immanuel Bible Church Jupiter, Florida I. Course Description and Objectives Jesus came—and will come again—to fulfill the Law and the Prophets (Matt 5:17). How, then, can we understand Him or His task if we do not know the contents of the Law and the Prophets? The better we understand “whatever was written in earlier times” (Rom 15:4), the more intimately we can know our God and Savior. Indeed, the apostle Paul testified that he stated “nothing but what the Prophets and Moses said was going to take place; that the Christ was to suffer, and that by reason of His resurrection from the dead He would be the first to proclaim light both to the Jewish people and to the Gentiles” (Acts 26:22-23). Introduction to Using Hebrew Language Tools seeks to introduce believers to biblical Hebrew and the language tools that facilitate its proper understanding. This introduction seeks to help believers: become acquainted with the Hebrew aleph beth become acquainted with frequently-occurring words in the Hebrew Scriptures become acquainted with the categories and use of Hebrew language tools recognize key terms and abbreviations used in Hebrew language tools better understand the author’s intended meaning better understand the New Testament, since its the foundation is the Old Testament recognize deviant teaching II. Course Requirements Participate in class activities and take a final assessment. 1 WEEK TOPIC 15 Introduction to course -

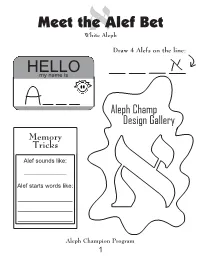

Aleph Champion Program

Meet the Alef Bet White` Aleph Draw 4 Alefs on the line: HELLOmy name is Aleph Champ Design Gallery Memory Tricks Alef sounds like: _____________ Alef starts words like: ____________ ____________ ____________ Aleph Champion `Program 1 “Hebrish” White` Aleph Rash Fat Ask `sh Ash `t Bat `sk Task Dash At Bask Apple __ pple America __ merica Art __ rt Alligator __ lligator Abba __ bba Antelope __ ntelope Ant Hand Call `nt Can’t `nd Sand `ll All Sent And Fall Aleph Champion Program 2 Count Me In White` Aleph How many ALEFS can you count? (circle them!) c i l b k ` c i g b ` k ` c i b ` h x w o e i a l A p v n c p d ` h c r b e ` k c e h w ` x l g p x k l p d l g ` r ` o d Final Count: # ___ Aleph Champion Program 3 Meet the Alef Bet White` Aleph Draw 4 Bets on the line: HELLOmy name is Aleph Champ Design Gallery Memory Tricks Bet sounds like: _____________ Bet starts words like: ____________ ____________ ____________ Aleph Champion ProgramA 4 Match ‘em up! White` Aleph A Alef ` a a Bet ` Alef A a a Alef A Bet ` a a Alef A Bet A a a Bet ` Alef ` a a Alef c ` b ` a c ` b ` A a a Bet ` A b c ` A a b ` A a a Bet b ` b A a c ` b ` A a a Alef A a b ` A c ` b ` a Aleph Champion Program 5 “Hebrish” White` Aleph See Bell Bare Ae Be Aell Tell `re Care He Sell Are Banana __ anana Arrow __ rrow Blue __ lue Birthday __ irthday Bayit __ ayit Abba __ bba Cat Bar Ball Aat Bat Aar Far `ll Fall Hat Car All Aleph Champion Program 6 Count Me In White` Aleph How many BETS can you count? A r ` o a ` w o A j b a ` n u A ` n d a ` u n b a k j ` A A k j ` g p ` A -

Grammar Chapter 1.Pdf

4 A Modern Grammar for Biblical Hebrew CHAPTER 1 THE HEBREW ALPHABET AND VOWELS Aleph) and the last) א The Hebrew alphabet consists entirely of consonants, the first being -Shin) were originally counted as one let) שׁ Sin) and) שׂ Taw). It has 23 letters, but) ת being ter, and thus it is sometimes said to have 22 letters. It is written from right to left, so that in -is last. The standard script for bibli שׁ is first and the letter א the letter ,אשׁ the word written cal Hebrew is called the square or Aramaic script. A. The Consonants 1. The Letters of the Alphabet Table 1.1. The Hebrew Alphabet Qoph ק Mem 19 מ Zayin 13 ז Aleph 7 א 1 Resh ר Nun 20 נ Heth 14 ח Beth 8 ב 2 Sin שׂ Samek 21 ס Teth 15 ט Gimel 9 ג 3 Shin שׁ Ayin 22 ע Yod 16 י Daleth 10 ד 4 Taw ת Pe 23 פ Kaph 17 כ Hey 11 ה 5 Tsade צ Lamed 18 ל Waw 12 ו 6 To master the Hebrew alphabet, first learn the signs, their names, and their alphabetical or- der. Do not be concerned with the phonetic values of the letters at this time. 2. Letters with Final Forms Five letters have final forms. Whenever one of these letters is the last letter in a word, it is written in its final form rather than its normal form. For example, the final form of Tsade is It is important to realize that the letter itself is the same; it is simply written .(צ contrast) ץ differently if it is the last letter in the word. -

Old Phrygian Inscriptions from Gordion: Toward A

OLD PHRYGIAN INSCRIPTIONSFROM GORDION: TOWARD A HISTORY OF THE PHRYGIAN ALPHABET1 (PLATES 67-74) JR HRYYSCarpenter's discussion in 1933 of the date of the Greektakeover of the Phoenician alphabet 2 stimulated a good deal of comment at the time, most of it attacking his late dating of the event.3 Some of the attacks were ill-founded and have been refuted.4 But with the passage of time Carpenter's modification of his original thesis, putting back the date of the takeover from the last quarter to the middle of the eighth century, has quietly gained wide acceptance.5 The excavations of Sir Leonard Woolley in 1936-37 at Al Mina by the mouth of the Orontes River have turned up evidence for a permanent Greek trading settle- ment of the eighth century before Christ, situated in a Semitic-speaking and a Semitic- writing land-a bilingual environment which Carpenter considered essential for the transmission of alphabetic writing from a Semitic- to a Greek-speakingpeople. Thus to Carpenter's date of ca. 750 B.C. there has been added a place which would seem to fulfill the conditions necessary for such a takeover, perhaps only one of a series of Greek settlements on the Levantine coast.6 The time, around 750 B.C., the required 1The fifty-one inscriptions presented here include eight which have appeared in Gordion preliminary reports. It is perhaps well (though repetitive) that all the Phrygian texts appear together in one place so that they may be conveniently available to those interested. A few brief Phrygian inscriptions which add little or nothing to the corpus are omitted here. -

Tombstones Bearing Hebrew Inscriptions in Aden

Arab. arch. epig. 2005: 16: 161–182 (2005) Printed in Singapore. All rights reserved Tombstones bearing Hebrew inscriptions in Aden Inscriptions on tombstones provide us with information about the family and A. Klein-Franke society of the deceased. Through a reading of these inscriptions the University of Cologne, individual is no longer anonymous. In addition to names, grave inscriptions Germany often contain information on an individual’s status and profession, offering us insights into the life of a community which include different classes and professions. The information emphasised in grave inscriptions reveals the values of a society and its traditions. This study investigates the corpus of Hebrew inscriptions on tombstones in Aden. Martin-Buber-Institut fu¨ r Judaistik, Universita¨tzuKo¨ln, Kerpener Str. 4, Keywords: Hebrew, epigraphy, Aden, calendrics, Judaism D – 50923 Ko¨ln email: [email protected] Introduction The common Hebrew words for cemetery are: Graveyards and tombstones provide us with an beˆt-qebaroˆt, the house of the burials, beˆt-‘almıˆn or insight into the life of people who are no longer beˆt-‘oˆlam, the everlasting house and beˆt-ha-h@ayyıˆm, alive. Tombstones tell us the name and age of the the house of the living (2). Among the Jews of Aden deceased person, and about when and where the and in Yemen the word for cemetery is meˇ‘araˆ (pl. deceased person lived. Sometimes the name of me‘aroˆt) which means cave. In Aden the ancient the deceased person gives an indication of family cemetery was called meˇ‘araˆ yesˇanaˆ, old cave (3). The origins. The style of the characters, the order of the ancient cemeteries were situated on the cliffs sur- words, and sentences in the inscription tell us of rounding the Crater. -

Modern Hebrew C-MATS ( Complete Messianic

The Complete Scriptures את Messianic Aleph Tav Revised 2nd Edition of the Tanakh (OT) with the First Edition of the B'rit Chadashah (NT) (Compiled by William H. Sanford Copyright © 2014) LARGE PRINT EDITION MODERN-HEBREW EDITION The Complete Scriptures את Messianic Aleph Tav Printed in the USA by Snowfall Press LARGE PRINT EDITION Copyright 2013 of Tanakh Copyright 2014 of B'rit Chadashah All rights reserved William H. Sanford [email protected] COPYRIGHT NOTICE Scriptures (C-MATS) is an English version of the Tanakh and B'rit את The Complete Messianic Aleph Tav Chadashah (Old and New covenant) originating from the 1987 King James Bible (KJV) which is in the Public Domain. However, this rendition of the KJV restores the missing Aleph/Tav Symbols throughout as well as key descriptive words which have been inserted in parenthesis to provide the reader a truer meaning of the original Hebrew text. Therefore, this work is a “Study Bible” and comes under copyright protection. This publication may be quoted in any form (written, visual, electronic, or audio), up to and inclusive of seventy (70) consecutive lines or verses, without express written permission of William H. Sanford, provided the verses quoted do not amount to a complete book and do not account for 10% or more of the total text of the work in which they are quoted. For orders please visit web address: www.AlephTavScriptures.com. Notice of copyright must appear as follows on either the title page or the copyright page of the work in which .Scriptures את it is being quoted as: “Scripture (or Content) taken from the Complete Messianic Aleph Tav Copyright 2014.