Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1943 Tehran Conference

O N F C E R N E A N R C H E E T T E E H C R N A E N R E C F O N Europe in December 1943 Tehran Territories – owned, occupied, controlled by: Axis Western Allies Soviet Union conference Neutral countries 28 November – Moscow SOVIET UNION UNITED Berlin KINGDOM 1 December NAZI 1943 GERMANY ITALY Tehran IRAN The first meeting between the Big Three took place at the Soviet Embassy in Tehran, Iran. Iran had been occupied by the UK and USSR since 1941. Joseph Stalin selected and insisted on the location. The conference was codenamed Eureka. After the conference, the Big Three issued two public statements: “Declaration of the Three Powers” and “Declaration on Iran”. They also signed a confidential document concerning military actions. World map in December 1943 © Institute of European Network Remembrance and Solidarity. This infographic may be downloaded and printed be downloaded may infographic This Network Remembrance and Solidarity. © Institute of European purposes. https://hi-storylessons.eu educational and not-for-profit only for (citing its source) in unchanged form 22–26 November Circumstances First Cairo Conference – Chiang Kai-shek (leader of the Republic of China), Churchill and Roosevelt 194314-24 January 23 August discuss the fight against Japan Casablanca Conference (Churchill, Soviet victory over Germany at the until unconditional surrender and Roosevelt and Charles de Gaulle) Battle of Kursk. The Red Army’s the reclaiming of seized territories. – where the leaders resolved offensive begins on the Eastern to continue fighting until an Front. unconditional surrender (without 194114 August any guarantees to the defeated F.D. -

Title of Thesis: ABSTRACT CLASSIFYING BIAS

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis Directed By: Dr. David Zajic, Ph.D. Our project extends previous algorithmic approaches to finding bias in large text corpora. We used multilingual topic modeling to examine language-specific bias in the English, Spanish, and Russian versions of Wikipedia. In particular, we placed Spanish articles discussing the Cold War on a Russian-English viewpoint spectrum based on similarity in topic distribution. We then crowdsourced human annotations of Spanish Wikipedia articles for comparison to the topic model. Our hypothesis was that human annotators and topic modeling algorithms would provide correlated results for bias. However, that was not the case. Our annotators indicated that humans were more perceptive of sentiment in article text than topic distribution, which suggests that our classifier provides a different perspective on a text’s bias. CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Gemstone Honors Program, University of Maryland, 2018 Advisory Committee: Dr. David Zajic, Chair Dr. Brian Butler Dr. Marine Carpuat Dr. Melanie Kill Dr. Philip Resnik Mr. Ed Summers © Copyright by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang 2018 Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincerest gratitude to our mentor, Dr. -

The Consideration of the Yalta Conference As an Executive Agreement

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 8-1-1973 The consideration of the Yalta Conference as an executive agreement John Brayman University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Brayman, John, "The consideration of the Yalta Conference as an executive agreement" (1973). Student Work. 372. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/372 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CONSIDERATION OF THE YALTA CONFERENCE AS AN EXECUTIVE AGREEMENT A Thesis Presented to the Department of History and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska at Omaha In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts John Brayman August, 1973 UMI Number: EP73010 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI EP73010 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 THESIS ACCEPTANCE Accepted for fee facility of The Graduate College of fee University of Nebraska at Omaha, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts, Graduate Committee: Name Departmin Chairman THE CONSITERATION GP :THS YALTA CONFERENCE AS AN EXECUTIVE AGREEMENT : The story of the Yalta Conference is a complex and a difficult one. -

In a Rather Emotional State?' the Labour Party and British Intervention in Greece, 1944-5

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE 'In a rather emotional state?' The Labour party and British intervention in Greece, 1944-5 AUTHORS Thorpe, Andrew JOURNAL The English Historical Review DEPOSITED IN ORE 12 February 2008 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/18097 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication 1 ‘IN A RATHER EMOTIONAL STATE’? THE LABOUR PARTY AND BRITISH INTERVENTION IN GREECE, 1944-45* Professor Andrew Thorpe Department of History University of Exeter Exeter EX4 4RJ Tel: 01392-264396 Fax: 01392-263305 Email: [email protected] 2 ‘IN A RATHER EMOTIONAL STATE’? THE LABOUR PARTY AND BRITISH INTERVENTION IN GREECE, 1944-45 As the Second World War drew towards a close, the leader of the Labour party, Clement Attlee, was well aware of the meagre and mediocre nature of his party’s representation in the House of Lords. With the Labour leader in the Lords, Lord Addison, he hatched a plan whereby a number of worthy Labour veterans from the Commons would be elevated to the upper house in the 1945 New Years Honours List. The plan, however, was derailed at the last moment. On 19 December Attlee wrote to tell Addison that ‘it is wiser to wait a bit. We don’t want by-elections at the present time with our people in a rather emotional state on Greece – the Com[munist]s so active’. -

2 the Reform of the Warsaw Pact

Research Collection Working Paper Learning from the enemy NATO as a model for the Warsaw Pact Author(s): Mastny, Vojtech Publication Date: 2001 Permanent Link: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-a-004148840 Rights / License: In Copyright - Non-Commercial Use Permitted This page was generated automatically upon download from the ETH Zurich Research Collection. For more information please consult the Terms of use. ETH Library Zürcher Beiträge zur Sicherheitspolitik und Konfliktforschung Nr.58 Vojtech Mastny Learning from the Enemy NATO as a Model for the Warsaw Pact Hrsg.: Kurt R. Spillmann und Andreas Wenger Forschungsstelle für Sicherheitspolitik und Konfliktanalyse der ETH Zürich CONTENTS Preface 5 Introduction 7 1 The Creation of the Warsaw Pact (1955-65) 9 2The Reform of the Warsaw Pact (1966-69) 19 3 The Demise of the Warsaw Pact (1969-91) 33 Conclusions 43 Abbreviations 45 Bibliography 47 coordinator of the Parallel History Project on NATO and the Warsaw PREFACE Pact (PHP), closely connected with the Center for Security Studies and Conflict Research (CSS) at the ETH Zürich. The CSS launched the PHP in 1999 together with the National Security Archive and the Cold War International History Project in Washington, DC, and the Institute of Military History, in Vienna. In 1955, the Warsaw Pact was created as a mirror image of NATO that could be negotiated away if favorable international conditions allowed Even though the Cold War is over, most military documents from this the Soviet Union to benefit from a simultaneous dissolution of both period are still being withheld for alleged or real security reasons. -

Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin: the Role of the Personal Factor in Success and Failure of the Grand Alliance

Geoffrey Roberts Professor of Irish history at the national University of CORK, member of the Royal historical society, senior research fellow Nobel Institute Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin: The Role of the Personal Factor in Success and Failure of the Grand Alliance Introduction It is often said that Grand Alliance was forced into existence by Hitler and fell apart as soon as Nazi Germany was defeated. But neither the formation of the Grand Alliance nor its collapse was inevitable. Both were the result of personal choices by the leaders of the alliance. Without Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin there would have been no Grand Alliance against Hitler in the sense that we understand that term today.60 Hitler posed a dire existential threat to both Britain and the Soviet Union, and to the United States the prospect of perpetual conflict. Britain had been at war with Germany since September 1939 and it is not surprising that the three states formed a military coalition when Hitler attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941 and then, in December, declared war on the United States. But the Grand Alliance that developed during the war was much more than a military coalition of convenience; it was a far-reaching political, economic and ideological collaboration. At the heart of this collaboration were the personal roles, outlooks and interactions of the three heads of state. Without the personal alliance of Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin – the Big Three as they became known during the war - the Grand Alliance would have been stillborn or would 60 “Grand Alliance” is the term commonly used in the west to describe the anti-Hitler coalition of Great Britain, the Soviet Union and the United States. -

GENERAL PHOTOGRAPHS File Subject Index

GENERAL PHOTOGRAPHS File Subject Index A (General) Abeokuta: the Alake of Abram, Morris B.: see A (General) Abruzzi: Duke of Absher, Franklin Roosevelt: see A (General) Adams, C.E.: see A (General) Adams, Charles, Dr. D.F., C.E., Laura Franklin Delano, Gladys, Dorothy Adams, Fred: see A (General) Adams, Frederick B. and Mrs. (Eilen W. Delano) Adams, Frederick B., Jr. Adams, William Adult Education Program Advertisements, Sears: see A (General) Advertising: Exhibits re: bill (1944) against false advertising Advertising: Seagram Distilleries Corporation Agresta, Fred Jr.: see A (General) Agriculture Agriculture: Cotton Production: Mexican Cotton Pickers Agriculture: Department of (photos by) Agriculture: Department of: Weather Bureau Agriculture: Dutchess County Agriculture: Farm Training Program Agriculture: Guayule Cultivation Agriculture: Holmes Foundry Company- Farm Plan, 1933 Agriculture: Land Sale Agriculture: Pig Slaughter Agriculture: Soil Conservation Agriculture: Surplus Commodities (Consumers' Guide) Aircraft (2) Aircraft, 1907- 1914 (2) Aircraft: Presidential Aircraft: World War II: see World War II: Aircraft Airmail Akihito, Crown Prince of Japan: Visit to Hyde Park, NY Akin, David Akiyama, Kunia: see A (General) Alabama Alaska Alaska, Matanuska Valley Albemarle Island Albert, Medora: see A (General) Albright, Catherine Isabelle: see A (General) Albright, Edward (Minister to Finland) Albright, Ethel Marie: see A (General) Albright, Joe Emma: see A (General) Alcantara, Heitormelo: see A (General) Alderson, Wrae: see A (General) Aldine, Charles: see A (General) Aldrich, Richard and Mrs. Margaret Chanler Alexander (son of Charles and Belva Alexander): see A (General) Alexander, John H. Alexitch, Vladimir Joseph Alford, Bradford: see A (General) Allen, Mrs. Idella: see A (General) 2 Allen, Mrs. Mary E.: see A (General) Allen, R.C. -

FDR Document Project

FOLLOW-UP ASSIGNMENT: FDR AND THE WORLD CRISIS: 1933-1945 SUBMITTED BY PAUL S RYKKEN, BLACK RIVER FALLS, WISCONSIN 26 July 2007 OVERVIEW As part of our concluding discussions at the July seminar, we were asked to create a letter, article, journal entry, briefing, press release, song, or classroom project that reflected a theme or revelation that resulted from our Hyde Park experience. Having taught American history for 28 years I have been “living” with FDR for many years and attempting to interpret him for students in my classes. I found the NEH experience to be incredibly enriching and thought-provoking and certainly am walking away from it with a much deeper appreciation for both Franklin and Eleanor. Of the wide ranging topics that we discussed, I was particularly taken with what we learned about Roosevelt’s fascination with maps and his sense of geography. The presentation by Dr. Alan Henrickson concerning FDR’s “mental maps” was especially instructive in this regard. The lesson plan that follows relates directly to what we learned about FDR as a communicator and global strategist during World War 2. I have often used the Fireside Chats in class (especially his first one) but will certainly add this one to my repertoire next year. The lesson plan is not especially original, but nevertheless offers excellent openings for working on the following skills: • Authentic document analysis • Enhanced understanding of the geography of the war, particularly concerning the early Pacific theater • Analysis of the power of persuasion by the President • Deeper sense of empathy concerning ordinary Americans during World War 2 1 DOCUMENT PROJECT: FDR AND THE WORLD CRISIS LESSON SET-UP In this activity students will be experiencing FDR’s Fireside Chat of February 23, 1942 concerning the progress of the war. -

Franklin D. Roosevelt Through Eleanor's Eyes

Franklin D. Roosevelt Through Eleanor’s eyes EPISODE TRANSCRIPT Listen to Presidential at http://wapo.st/presidential This transcript was run through an automated transcription service and then lightly edited for clarity. There may be typos or small discrepancies from the podcast audio. LILLIAN CUNNINGHAM: March 4, 1933. A grey and cold Inauguration Day. Outgoing president Herbert Hoover and incoming president Franklin Delano Roosevelt had on their winter coats, and they had blankets wrapped around their legs as they rode side-by-side in an open touring car from the White House to the East Portico of the Capitol building for Roosevelt's swearing in. There were secret ramps set up so that FDR could wheel himself nearly all the way to the stage. And then with the help of his son James, he propped himself out of the wheel chair and walked slowly to the lectern. He stared out at the crowd of Americans who were gathered there to watch his inauguration during these dark days of the Great Depression, and he took the oath of office. FRANKLIN DELANO ROOSEVELT CLIP LILLIAN CUNNINGHAM: Roosevelt's hand was on his family's 250-year-old Dutch bible. The page was open to 1 Corinthians 13, which has the words: “Love is patient. Love is kind. It does not envy. It does not boast. It is not proud. It does not dishonor others. It is not self-seeking. It is not easily angered. It keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not delight in evil, but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes. -

History, Grand Strategy and NATO Enlargement 145 History, Grand Strategy And

History, Grand Strategy and NATO Enlargement 145 History, Grand Strategy and NATO Enlargement ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ John Lewis Gaddis Some principles of strategy are so basic that when stated they sound like platitudes: treat former enemies magnanimously; do not take on unnecessary new ones; keep the big picture in view; balance ends and means; avoid emotion and isolation in making decisions; be willing to acknowledge error. All fairly straightforward, one might think. Who could object to them? And yet – consider the Clinton administration’s single most important foreign-policy initiative: the decision to expand NATO to include Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic. NATO enlargement, I believe, manages to violate every one of the strategic principles just mentioned. Perhaps that is why historians – normally so contentious – are in uncharacteristic agreement: with remarkably few exceptions, they see NATO enlargement as ill-conceived, ill-timed, and above all ill-suited to the realities of the post-Cold War world. Indeed I can recall no other moment in my own experience as a practising historian at which there was less support, within the community of historians, for an announced policy position. A significant gap has thus opened between those who make grand strategy and those who reflect upon it: on this issue at least, official and accumulated wisdom are pointing in very different directions. This article focuses on how this has happened, which leads us back to a list of basic principles for grand strategy. First, consider the magnanimous treatment of defeated adversaries. There are three great points of reference here – 1815–18, 1918–19 and 1945–48 – and historians are in general accord as to the lessons to be drawn from each. -

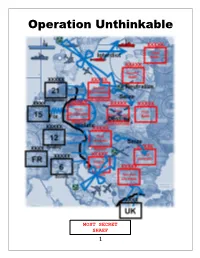

Operation Unthinkable

Operation Unthinkable MOST SECRET SHAEF 1 Mountaineer Game Design by Bob Hatcher I Setting The Game Map & Setup Page 3 Turn Sequence Overview Page 5 Victory Conditions Page 5 II Game Characteristics Geography and Economics Page 6 Allied Forces Page 7 Soviet Forces Page 7 Neutrals Page 8 Units Page 9 III Detailed Sequence of Events Page 11 IV Advanced Rules Page 14 V Parts list Page 16 VI Statistics Page 17 2 I FIGHTING OPERATION UNTHINKABLE At the end of May 1945, it is highly doubtful the Soviet Government is going to allow democratic processes in the countries they occupy. As Prime Minister Churchill feared, it appears the Russians are not going to honor the agreements made between Allies concerning the future of Central and Southern Europe. To impose the will of the United States, The British Empire, and their Allies, the Joint Planning Staff draws up plans for Operation Unthinkable, a plan completely dependent on strategic surprise and the support of other European powers, including those they liberate. Outnumbered 2 to 1 in men and materiel, the Allies will need every advantage in the opening offensive in a war that many thought was over for Europe. D Day is set for 1 July 1945… The Game Map & Setup The game map is divided into territories color-coded based on original national ownership. Allied territory is green and Soviet red. Large city areas are circular and may comprise more than one zone. Territories have a number in each area that indicates their value. There is a timeline chart for tracking turns and events, a chart for national morale, a chart for tracking the formation of NATO, and a chart for random events. -

H-Diplo Roundtables, Vol. XIV, No. 8

2012 H-Diplo Roundtable Editors: Thomas Maddux and Diane Labrosse Roundtable Web/Production Editor: George Fujii H-Diplo Roundtable Review www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables Commissioned for H-Diplo by Thomas Maddux Volume XIV, No. 8 (2012) Introduction by Thomas Maddux, California State 12 November 2012 University, Northridge Frank Costigliola. Roosevelt's Lost Alliances: How Personal Politics Helped Start the Cold War. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012. ISBN: 9780691121291 (cloth, $35.00); 9781400839520 (eBook, $35.00). Stable URL: http://www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables/PDF/Roundtable-XIV-8.pdf Contents Introduction by Thomas Maddux, California State University Northridge............................... 2 Review by Michaela Hoenicke Moore, University of Iowa ....................................................... 8 Review by Michael Holzman, Independent Scholar ............................................................... 15 Review by J Simon Rofe, SOAS, University of London ............................................................ 18 Review by David F. Schmitz, Whitman College ....................................................................... 21 Review by Michael Sherry, Northwestern University ............................................................. 25 Review by Katherine A. S. Sibley, Saint Joseph’s University ................................................... 29 Author’s Response by Frank Costigliola, University of Connecticut ....................................... 33 Copyright © 2012 H-Net: Humanities and