A Brief Review of the Price of Novels in the Ming and Qing Dynasties

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Challenges-And-Reforms-In-Urban

©2016 Centre for Liveable Cities (CLC), Singapore and Development Research Center of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China (DRC). All rights reserved. CLC is a division of Set up in 2008 by the Ministry of National Development and the Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources, the Centre for Liveable Cities (CLC) has as its mission “to distil, create and share knowledge on liveable and sustainable cities”. CLC’s work spans four main areas — Research, Capability Development, Knowledge Platforms, and Advisory. Through these activities, CLC hopes to provide urban leaders and practitioners with the knowledge and support needed to make our cities better. The Development Research Center of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China (DRC) is a policy research and consulting institution directly under the State Council, the central government of the People's Republic of China. Its major function is to undertake research on the overall, comprehensive, strategic and long-term issues in economic and social development, as well as pressing problems related to reform and opening up of China’s economy, and provide policy options and consulting advice to the CPC Central Committee and the State Council. Centre for Liveable Cities Development Research Center of the State 45 Maxwell Road Council of the People’s Republic of China #07-01 The URA Centre 225 Chaoyangmenwai Avenue Singapore 069118 Dongcheng District, Beijing 100010, China Website: www.clc.gov.sg Website: www.en.drc.gov.cn ISBN #9789814765305 (print) e-ISBN #9789814765350 (e-book) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without prior written permission of the publisher. -

4 China: Government Policy and Tourism Development

China: Government Policy 4 and Tourism Development Trevor H. B. Sofield Introduction In 2015, according to the China National Tourism Administration (CNTA), China welcomed 133.8 million inbound visitors; it witnessed 130 million outbound trips by its citizens; and more than 4 billion Chinese residents took domestic trips around the country. International arrivals generated almost US$60 billion, outbound tour- ists from China spent an estimated US$229 billion (GfK, 2016), and domestic tour- ism generated ¥(Yuan)3.3 trillion or US$491 billion (CNTA, 2016). By 2020, Beijing anticipates that domestic tourists will spend ¥5.5 trillion yuan a year, more than double the total in 2013, to account for 5 percent of the country’s GDP. In 2014, the combined contribution from all three components of the tourism industry to GDP, covering direct and indirect expenditure and investment, in China was ¥5.8 trillion (US$863 billion), comprising 9.4% of GDP. Government forecasts suggest this figure will rise to ¥11.4 trillion (US$1.7 trillion) by 2025, accounting for 10.3% of GDP (Wang et al., 2016). Few governments in the world have approached tourism development with the same degree of control and coordination as China, and certainly not with outcomes numbering visitation and visitor expenditure in the billions in such a short period of time. In 1949 when Mao Zedong and the Communist Party of China (CCP) achieved complete control over mainland China, his government effectively banned all domestic tourism by making internal movement around the country illegal (CPC officials excepted), tourism development was removed from the package of accept- able development streams as a bourgeoisie activity, and international visitation was a diplomatic tool to showcase the Communist Party’s achievements, that was restricted to a relative handful of ‘friends of China’. -

Administrative Law and the Making of the First <I>Da Qing Huidian</I>

$GPLQLVWUDWLYH/DZDQGWKH0DNLQJRIWKH)LUVW'D4LQJ+XLGLDQ 0DFDEH.HOLKHU /DWH,PSHULDO&KLQD9ROXPH1XPEHU-XQHSS $UWLFOH 3XEOLVKHGE\-RKQV+RSNLQV8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV '2,ODWH )RUDGGLWLRQDOLQIRUPDWLRQDERXWWKLVDUWLFOH KWWSVPXVHMKXHGXDUWLFOH Access provided by Indiana University Libraries (4 Jul 2016 00:49 GMT) Administrative Law and the Making of the First Da Qing Huidian Macabe Keliher, West Virginia University* In the fall of 1690, after decades of development and deliberation, the Qing court issued the first edition of the collected statutes of the dynasty. This hundred-volume compilation pulled together all organizational stipulations for government personnel, as well as the institutional regulations and codes for administrative procedure and activity. It incorporated rules pertaining to political and administrative actors, including the emperor, and outlined the organization and operations of every office and political station of the Qing state. These compiled regulations were, for all intents and purposes, the administrative law of the Qing Dynasty.1 This was the Da Qing huidian, and it laid the ∗ The idea for this article developed in a conversation with my dissertation advisor, Mark Elliott, whose advice and comments on numerous drafts have been invaluable. Michael Chang read and commented on an early draft as a panel discussant at the 2014 Northeast AAS conference, and continued to provide valuable feedback on subsequent revisions in his role as an editor for this journal. I would also like to thank Michael Szonyi and Ian M. Milller for their detailed comments, as well as John Greggory, Nancy Park, David Porter, Teemu Ruskola, and the two anonymous reviewers. Additional research and final revisions were completed during my year as a Jerome Hall Postdoctoral Fellow at Indiana University Maurer School of Law. -

The History of the Yen Bloc Before the Second World War

@.PPO8PPTJL ࢎҮ 1.ಕ BOZQSJOUJOH QNBD ȇ ȇ Destined to Fail? The History of the Yen Bloc before the Second World War Woosik Moon The formation of yen bloc did not result in the economic and monetary integration of East Asian economies. Rather it led to the increasing disintegration of East Asian economies. Compared to Japan, Asian regions and countries had to suffer from higher inflation. In fact, the farther the countries were away from Japan, the more their central banks had to print the money and the higher their inflations were. Moreover, the income gap between Japan and other Asian countries widened. It means that the regionalization centered on Japanese yen was destined to fail, suggesting that the Co-prosperity Area was nothing but a strategy of regional dominance, not of regional cooperation. The impact was quite long lasting because it still haunts East Asian countries, contributing to the nourishment of their distrust vis-à-vis Japan, and throws a shadow on the recent monetary and financial cooperation movements in East Asia. This experience highlights the importance of responsible actions on the part of leading countries to boost regional solidarity and cohesion for the viability and sustainability of regional monetary system. 1. Introduction There is now a growing literature that argues for closer monetary and financial cooperation in East Asia, reflecting rising economic and political interdependence between countries in the region. If such a cooperation happens, leading countries should assume corresponding responsibilities. For, the viability of the system depends on their responsible actions to boost regional solidarity and cohesion. -

Climbing the Ladder of Success in the Imperial China: Chang Chien's

Open Access Library Journal Climbing the Ladder of Success in the Imperial China: Chang Chien’s Examination Life Shun-Chih Sun Department of Translation and Interpretation Studies, Chang Jung Christian University, Tainan, Chinese Taipei Email: [email protected] Received 7 August 2015; accepted 22 August 2015; published 28 August 2015 Copyright © 2015 by author and OALib. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Chang Chien (1853-1926) was a native of Nant’ung, Kiangsu. In spite of the Various works on Chang Chien, which testify to the significance of his role in modern China, Chang Chien’s examina- tion life is still not well-researched. The purposes of this paper are firstly, to analyze Chang Chien’s examination life systematically and clearly in the hope that it may become a useful reference for researchers on modern China, and secondly, to stimulate scholars for further research. This paper depends more on basic source materials rather than second-hand data. Among various source materials, Chang Chien’s Diary, The Nine Records of Chang Chien and The Complete Work of Chang Chien are the most important. Chang Chien’s examination life has close connection with the Im- perial China’s Civil Service examination and the establishment of New Education system of China in the late Ch’ing Period. Chang Chien’s examination life can be divided into three periods: 1) The period to Siu-ts’ai diploma (licentiate). 2) The period to Chu-jen diploma (a successful candidate for provincial examination). -

The Dawn of the Digital Yuan: China’S Central Bank Digital Currency and Its Implications

The Dawn of the Digital Yuan: China’s Central Bank Digital Currency and Its Implications Mahima Duggal ASIA PAPER June 2021 The Dawn of the Digital Yuan: China’s Central Bank Digital Currency and Its Implications Mahima Duggal © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “The Dawn of the Digital Yuan: China’s Central Bank Digital Currency and Its Implications” is an Asia Paper published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged. © ISDP, 2021 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-21-4 Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. +46-841056953; Fax. +46-86403370 Email: [email protected] Editorial correspondence should be directed to the address provided above (preferably by email). Contents Summary ............................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ......................................................................................................... -

Utopia/Wutuobang As a Travelling Marker of Time*

The Historical Journal, , (), pp. – © The Author(s), . Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/./), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is unaltered and is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press must be obtained for commercial re-use or in order to create a derivative work. doi:./SX UTOPIA/WUTUOBANG AS A TRAVELLING MARKER OF TIME* LORENZO ANDOLFATTO Heidelberg University ABSTRACT. This article argues for the understanding of ‘utopia’ as a cultural marker whose appearance in history is functional to the a posteriori chronologization (or typification) of historical time. I develop this argument via a comparative analysis of utopia between China and Europe. Utopia is a marker of modernity: the coinage of the word wutuobang (‘utopia’) in Chinese around is analogous and complementary to More’s invention of Utopia in ,inthatbothrepresent attempts at the conceptualizations of displaced imaginaries, encounters with radical forms of otherness – the European ‘discovery’ of the ‘New World’ during the Renaissance on the one hand, and early modern China’sown‘Westphalian’ refashioning on the other. In fact, a steady stream of utopian con- jecturing seems to mark the latter: from the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom borne out of the Opium wars, via the utopian tendencies of late Qing fiction in the works of literati such as Li Ruzhen, Biheguan Zhuren, Lu Shi’e, Wu Jianren, Xiaoran Yusheng, and Xu Zhiyan, to the reformer Kang Youwei’s monumental treatise Datong shu. -

Chinas Examination Hell the Civil Service Examinations of Imperial China 1St Edition Free

CHINAS EXAMINATION HELL THE CIVIL SERVICE EXAMINATIONS OF IMPERIAL CHINA 1ST EDITION FREE Author: Ichisada Miyazaki ISBN: 9780300026399 Download Link: CLICK HERE The Chinese Imperial Examination System Transcriptions Revised Romanization gwageo. During the reign of Emperor Xizong of Jin r. It was called the nine-rank system. After the collapse of the Han dynastythe Taixue was reduced to just 19 teaching positions and 1, students but climbed back to 7, students under the Jin dynasty — The Hanlin Academy played a central role in the careers of examination graduates during the Ming dynasty. During the Tang period, a set curricular schedule took shape where the three steps of reading, writing, and the composition of texts had to be learnt before students could enter state academies. Western perception of China in the 18th century admired the Chinese bureaucratic system as favourable over European governments for its seeming meritocracy. In the Song dynasty — the imperial examinations became the primary method of recruitment for official posts. Stanford: Stanford University Press. By the time of the Song dynasty, the two highest military posts of Minister of War and Chief of Staff were both reserved for civil servants. Liu, Haifeng The Chinas Examination Hell The Civil Service Examinations of Imperial China 1st edition of the military examination were more elaborate during the Qing than ever before. China's Examination Hell: The Civil Service Examinations of Imperial China There was almost no other way to hit the really big time. Average rating 3. Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. He and the assistant examiners were dispatched on imperial order from the Ministry of Rites. -

A Chinese Opinion on Leprosy, Being a Tpanslation of A

A CHINESE OPINION ON LEPROSY, BEINGA TPANSLATIONOF A CHAPTERFROM THE MEDICALSTANDARD-WORK Imperial edition of the Golden Mirror for the medical class1) BY B. A. J. VAN WETTUM. ' LEPROSY. Leprosy always takes its origin from pestilential miasms. Its causes are three in number, and five injurious forms are distinguished. Also five forms with mortification of some part, which make it a most loathsome disease. By self-restraint in the first stage of his illness, the patient may perhaps preserve his COMMENTARY. The ancient name of this disease was - (pestilential "wind") This", JI, means "wind with poison in it". 1) First chapter of the 87tb volume. It was published in the 7th year of the reign of K'ien-Lung,A.D. 1742. According to Wylie, it is one of the best works of moderntimes for general medicalinformation. (A Wylie, Notes on Chineseliterature, pag. 82). It bas a 2) The. above forms the text of the essay. the shape of $ (rhyme) and consistsof four lines each of seven words. In the arrangementof these, not much care is taken with to and regard 2fi: fà (rhytm) flfi (rhyme). 3) The true meaningof the character as occurringin the present essay,is not 257 The Canon 4) says: "this If. means that the blood and the vital ' ' fluid are hot and spoiled". The vital fluid is no longer pure. That is the reason why the nosebone gets injured, the color of the face destroyed and the skin is covered with boils and sores. A poisonous wind has stationed itself in the veins and does not go away. -

Analysi of Dream of the Red Chamber

MULTIPLE AUTHORS DETECTION: A QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS OF DREAM OF THE RED CHAMBER XIANFENG HU, YANG WANG, AND QIANG WU A bs t r a c t . Inspired by the authorship controversy of Dream of the Red Chamber and the applica- tion of machine learning in the study of literary stylometry, we develop a rigorous new method for the mathematical analysis of authorship by testing for a so-called chrono-divide in writing styles. Our method incorporates some of the latest advances in the study of authorship attribution, par- ticularly techniques from support vector machines. By introducing the notion of relative frequency as a feature ranking metric our method proves to be highly e↵ective and robust. Applying our method to the Cheng-Gao version of Dream of the Red Chamber has led to con- vincing if not irrefutable evidence that the first 80 chapters and the last 40 chapters of the book were written by two di↵erent authors. Furthermore, our analysis has unexpectedly provided strong support to the hypothesis that Chapter 67 was not the work of Cao Xueqin either. We have also tested our method to the other three Great Classical Novels in Chinese. As expected no chrono-divides have been found. This provides further evidence of the robustness of our method. 1. In t r o du c t ion Dream of the Red Chamber (˘¢â) by Cao Xueqin (˘»é) is one of China’s Four Great Classical Novels. For more than one and a half centuries it has been widely acknowledged as the greatest literary masterpiece ever written in the history of Chinese literature. -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

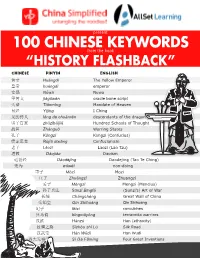

100 Chinese Keywords

present 100 CHINESE KEYWORDS from the book “HISTORY FLASHBACK” Chinese Pinyin English 黄帝 Huángdì The Yellow Emperor 皇帝 huángdì emperor 女娲 Nǚwā Nuwa 甲骨文 jiǎgǔwén oracle bone script 天命 Tiānmìng Mandate of Heaven 易经 Yìjīng I Ching 龙的传人 lóng de chuánrén descendants of the dragon 诸子百家 zhūzǐbǎijiā Hundred Schools of Thought 战国 Zhànguó Warring States 孔子 Kǒngzǐ Kongzi (Confucius) 儒家思想 Rújiā sīxiǎng Confucianism 老子 Lǎozǐ Laozi (Lao Tzu) 道教 Dàojiào Daoism 道德经 Dàodéjīng Daodejing (Tao Te Ching) 无为 wúwéi non-doing 墨子 Mòzǐ Mozi 庄子 Zhuāngzǐ Zhuangzi 孟子 Mèngzǐ Mengzi (Mencius) 孙子兵法 Sūnzǐ Bīngfǎ (Sunzi’s) Art of War 长城 Chángchéng Great Wall of China 秦始皇 Qín Shǐhuáng Qin Shihuang 妃子 fēizi concubines 兵马俑 bīngmǎyǒng terracotta warriors 汉族 Hànzú Han (ethnicity) 丝绸之路 Sīchóu zhī Lù Silk Road 汉武帝 Hàn Wǔdì Han Wudi 四大发明 Sì Dà Fāmíng Four Great Inventions Chinese Pinyin English 指南针 zhǐnánzhēn compass 火药 huǒyào gunpowder 造纸术 zàozhǐshù paper-making 印刷术 yìnshuāshù printing press 司马迁 Sīmǎ Qiān Sima Qian 史记 Shǐjì Records of the Grand Historian 太监 tàijiàn eunuch 三国 Sānguó Three Kingdoms (period) 竹林七贤 Zhúlín Qīxián Seven Bamboo Sages 花木兰 Huā Mùlán Hua Mulan 京杭大运河 Jīng-Háng Dàyùnhé Grand Canal 佛教 Fójiào Buddhism 武则天 Wǔ Zétiān Wu Zetian 四大美女 Sì Dà Měinǚ Four Great Beauties 唐诗 Tángshī Tang poetry 李白 Lǐ Bái Li Bai 杜甫 Dù Fǔ Du Fu Along the River During the Qingming 清明上河图 Qīngmíng Shàng Hé Tú Festival (painting) 科举 kējǔ imperial examination system 西藏 Xīzàng Tibet, Tibetan 书法 shūfǎ calligraphy 蒙古 Měnggǔ Mongolia, Mongolian 成吉思汗 Chéngjí Sīhán Genghis Khan 忽必烈 Hūbìliè Kublai