Love‟S Incompatibility with War: Understanding the Question Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summaries of the Trojan Cycle Search the GML Advanced

Document belonging to the Greek Mythology Link, a web site created by Carlos Parada, author of Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology Characters • Places • Topics • Images • Bibliography • PDF Editions About • Copyright © 1997 Carlos Parada and Maicar Förlag. Summaries of the Trojan Cycle Search the GML advanced Sections in this Page Introduction Trojan Cycle: Cypria Iliad (Synopsis) Aethiopis Little Iliad Sack of Ilium Returns Odyssey (Synopsis) Telegony Other works on the Trojan War Bibliography Introduction and Definition of terms The so called Epic Cycle is sometimes referred to with the term Epic Fragments since just fragments is all that remain of them. Some of these fragments contain details about the Theban wars (the war of the SEVEN and that of the EPIGONI), others about the prowesses of Heracles 1 and Theseus, others about the origin of the gods, and still others about events related to the Trojan War. The latter, called Trojan Cycle, narrate events that occurred before the war (Cypria), during the war (Aethiopis, Little Iliad, and Sack of Ilium ), and after the war (Returns, and Telegony). The term epic (derived from Greek épos = word, song) is generally applied to narrative poems which describe the deeds of heroes in war, an astounding process of mutual destruction that periodically and frequently affects mankind. This kind of poetry was composed in early times, being chanted by minstrels during the 'Dark Ages'—before 800 BC—and later written down during the Archaic period— from c. 700 BC). Greek Epic is the earliest surviving form of Greek (and therefore "Western") literature, and precedes lyric poetry, elegy, drama, history, philosophy, mythography, etc. -

HOMERIC-ILIAD.Pdf

Homeric Iliad Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power Contents Rhapsody 1 Rhapsody 2 Rhapsody 3 Rhapsody 4 Rhapsody 5 Rhapsody 6 Rhapsody 7 Rhapsody 8 Rhapsody 9 Rhapsody 10 Rhapsody 11 Rhapsody 12 Rhapsody 13 Rhapsody 14 Rhapsody 15 Rhapsody 16 Rhapsody 17 Rhapsody 18 Rhapsody 19 Rhapsody 20 Rhapsody 21 Rhapsody 22 Rhapsody 23 Rhapsody 24 Homeric Iliad Rhapsody 1 Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power [1] Anger [mēnis], goddess, sing it, of Achilles, son of Peleus— 2 disastrous [oulomenē] anger that made countless pains [algea] for the Achaeans, 3 and many steadfast lives [psūkhai] it drove down to Hādēs, 4 heroes’ lives, but their bodies it made prizes for dogs [5] and for all birds, and the Will of Zeus was reaching its fulfillment [telos]— 6 sing starting from the point where the two—I now see it—first had a falling out, engaging in strife [eris], 7 I mean, [Agamemnon] the son of Atreus, lord of men, and radiant Achilles. 8 So, which one of the gods was it who impelled the two to fight with each other in strife [eris]? 9 It was [Apollo] the son of Leto and of Zeus. For he [= Apollo], infuriated at the king [= Agamemnon], [10] caused an evil disease to arise throughout the mass of warriors, and the people were getting destroyed, because the son of Atreus had dishonored Khrysēs his priest. Now Khrysēs had come to the ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter, and had brought with him a great ransom [apoina]: moreover he bore in his hand the scepter of Apollo wreathed with a suppliant’s wreath [15] and he besought the Achaeans, but most of all the two sons of Atreus, who were their chiefs. -

Vergil's Nisus and the Language of Self-Sacrifice In

Vergil’s Nisus and the Language of Self-Sacrifice in Paradise Lost LEAH WHITTINGTON Princeton University When the Son of God offers to die for mankind in book 3 of Paradise Lost (1667), readers who have been tempted to join the devil’s party for the first two books of the poem confront an unsettling dramatic scene: the assembly in heaven is staged as a mirror image of the demonic council at Pandemonium. The listening host suddenly grows quiet, and a solitary hero figure emerges out of the silence to take on the burden of raising the collective fortune. Placed beside the Son’s promise to atone for man’s sin with his death, Satan’s exploratory mission to earth comes into focus as a fallen reflection of self-sacrifice, a self-aggrandiz- ing perversion of the poem’s heroic ideal now articulated in the Son. This moment of internal self-reference has often been identified as part of Milton’s didactic strategy to confront the reader with proof of his own fallenness,1 but it is less often recognized that the Son’s speech to the angelic host makes use of an allusion that gives it a central place in the story of Milton’s engagement with classical epic.2 When the Son 1. See Stanley Fish, Surprised by Sin (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971). Fish famously argues that the heroic portrayal of Satan is part of a larger narrative strategy by which Milton provokes the reader ‘‘with evidence of his corruption’’ and forces him ‘‘to refine his perceptions so that his understanding will be once more proportionable to truth’’ (xiii). -

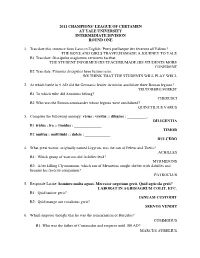

Intermediate Division Round One

2011 CHAMPIONS’ LEAGUE OF CERTAMEN AT YALE UNIVERSITY INTERMEDIATE DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. Translate this sentence from Latin to English: Pueri puellaeque iter fecerunt ad Yalium? THE BOYS AND GIRLS TRAVELED/MADE A JOURNEY TO YALE B1 Translate: Discipulus magistrum certiorem facebat. THE STUDENT INFORMED HIS TEACHER/MADE HIS STUDENTS MORE CONFIDENT B2 Translate: Putamus discipulos bene lusuros esse. WE THINK THAT THE STUDENTS WILL PLAY WELL 2. At which battle in 9 AD did the Germanic leader Arminius annihilate three Roman legions? TEUTOBERG FOREST B1 To which tribe did Arminius belong? CHERUSCI B2 Who was the Roman commander whose legions were annihilated? QUINCTILIUS VARUS 3. Complete the following analogy: vrus : vrits :: diligns : __________. DLIGENTIA B1 rtus : ra :: timidus : ______________ TIMOR B2 multus : multitd :: dulcis : _____________ DULCD 4. What great warior, originally named Ligyron, was the son of Peleus and Thetis? ACHILLES B1: Which group of warriors did Achilles lead? MYRMIDONS B2: After killing Clytonomous, which son of Menoetius sought shelter with Achilles and became his favorite companion? PATROCLUS 5. Responde Latine: homines multa agunt. Mercator negotium gerit. Quid agricola gerit? LABORAT IN AGRIS/AGRUM COLIT, ETC. B1: Quid ianitor gerit? IANUAM CUSTODIT B2: Quid mango aut venalicius gerit? SERVOS VENDIT 6. Which emperor thought that he was the reincarnation of Hercules? COMMODUS B1. Who was the father of Commodus and emperor until 180 AD? MARCUS AURELIUS B2. What was the name of Commodus’ mistress, believed to have been a Christian? MARCIA 7. Make the phrase “lx t vrits” accusative plural. LCS T VRITTS B1. Make “lcs t vritts” genitive plural. -

Getting Acquainted with the Myths Search the GML Advanced

Document belonging to the Greek Mythology Link, a web site created by Carlos Parada, author of Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology Characters • Places • Topics • Images • Bibliography • PDF Editions About • Copyright © 1997 Carlos Parada and Maicar Förlag. Getting acquainted with the myths Search the GML advanced Sections in this Page I. Getting acquainted with the myths II. Four "gateways" of mythology III. A strategy for reading the myths I. Getting acquainted with the myths What "getting acquainted" may mean We'll first try to clarify the meaning that the expression "getting acquainted" may have in this context: In a practical sense, I mean by "acquaintance" a general knowledge of the tales of mythology, including how they relate to each other. This concept includes neither analysis nor interpretation of the myths nor plunging too deep into one tale or another. In another sense, the expression "getting acquainted" has further implications that deserve elucidation: First of all, let us remember that we naturally investigate what we ignore, and not what we already know; accordingly, we set out to study the myths not because we feel we know them but because we feel we know nothing or very little about them. I mention this obvious circumstance because I believe that we should bear in mind that, in this respect, we are not in the same position as our remote ancestors, who may be assumed to have made their acquaintance with the myths more or less in the same way one learns one's mother tongue, and consequently did not have to study them in any way. -

Senecan Tragedy and Virgil's Aeneid: Repetition and Reversal

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 Senecan Tragedy and Virgil's Aeneid: Repetition and Reversal Timothy Hanford Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/427 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SENECAN TRAGEDY AND VIRGIL’S AENEID: REPETITION AND REVERSAL by TIMOTHY HANFORD A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Classics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 ©2014 TIMOTHY HANFORD All Rights Reserved ii This dissertation has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in Classics in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Ronnie Ancona ________________ _______________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Dee L. Clayman ________________ _______________________________ Date Executive Officer James Ker Joel Lidov Craig Williams Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract SENECAN TRAGEDY AND VIRGIL’S AENEID: REPETITION AND REVERSAL by Timothy Hanford Advisor: Professor Ronnie Ancona This dissertation explores the relationship between Senecan tragedy and Virgil’s Aeneid, both on close linguistic as well as larger thematic levels. Senecan tragic characters and choruses often echo the language of Virgil’s epic in provocative ways; these constitute a contrastive reworking of the original Virgilian contents and context, one that has not to date been fully considered by scholars. -

128 13) It Is to Be Noted That the Theory of These Remarks Is Not Put

128 13) It is to be noted that the theory of these remarks is not put into practice in the Il.: it is taken for granted that Trojans and Greeks communicate with each other without the help of interpreters. The author of the HomericHymn to Aphrodite, indeed, goes one step further, since he makes Aphrodite (who pretends to be a Phrygian princess) say to the Trojan Anchises: (113-6) On this subject see further: J. Werner, NichtgriechischeSprachen imBewusstsein der antikenGriechen, in: P. Händel, W. Meid (ed.), Festschrift für Robert Muth(Innsbruck 1983), 583-95. THE FIRST SONG OF DEMODOCUS The quarrel of Odysseus and Achilles, about which the Phaeacian singer Demodocus sings at the beginning of a feast being held in Odysseus' honour, is neither attested to by any reliable tradition nor easily explicable from the internal standpoint of the epics'). It is thus not surprising that alongside attempts to discover the tradition to which it should be attributed, it has been argued that the subject of Demodocus' first song was simply invented by Homer. In his article on the Odysseyin RE, P. Von der Mfhll assumed that the quarrel of Odysseus and Achilles was an autoschediasma created with the intention of supplying Demodocus with material for his performance2). Though Von der Mfhll later abandoned this theory in favour of the hypothesis that the episode could be traced back to the Cypria3), the view that Demodocus' first song is an "Augenblickserfindung" was revived by W. Marg. According to Marg's theory, the quarrel between Odysseus and Achilles was invented in order to generate an allusion to the proem of the Iliad, to which it bears a striking resemblance4). -

On History and Political Thought in Homer's Iliad, with a Focus on Books

Defining Politics: On History and Political Thought in Homer’s Iliad, With a Focus on Books 1-9 by Andrew M. Gross A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science University of Toronto © Copyright by Andrew M. Gross 2017 Defining Politics: On History and Political Thought in Homer’s Iliad, With a Focus on Books 1-9 Andrew M. Gross Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science University of Toronto 2017 ii Abstract The Iliad is a work of great literary complexity that contains profound insights and a wide- ranging account of the human condition. Some of the most important recent scholarly work on the poem has also emphasized the political dimension of Homer’s account. In this dissertation, I aim to contribute to our understanding of the Iliad as a work of political thought. Focusing on books 1 through 9 of the Iliad, I will try to show how we can discover in it a consistent chronological or historical account, even though at many points that history is not presented in a linear way, in the poem itself. Through various references we are able to discern an historical account of the entire cosmic order. Homer focuses on the newly established Olympian gods and, therewith, their need to enforce the crucial separation between themselves and human beings: that is, between their own status as immortals, and our condition as mortals. Homer’s history of the Trojan War, in turn, conveys crucial lessons about politics and the human condition. The dissertation traces the history of the war as it emerged from a private struggle and developed into a public war. -

Homer and Hesiod

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (Classical Studies) Classical Studies at Penn 1-1-1997 Homer and Hesiod Ralph M. Rosen University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Rosen, R. M. (1997). Homer and Hesiod. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/7 Postprint version. Published in A New Companion to Homer, edited by Barry Powell and Ian Morris, Mnemosyne: Bibliotheca classica Batava, Supplementum 163 (New York: Brill, 1997), pages 463-488. The author has asserted his right to include this material in ScholarlyCommons@Penn. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Homer and Hesiod Abstract One of the most frustrating aspects of Homeric studies is that so little literary material outside the Homeric corpus itself survives to enhance our understanding of the cultural landscape of the period. Recent scholarship suggests that a large and diverse poetic tradition lay behind the figure we refer to as "Homer," but little of it survives. Indeed we have little continuous written Greek for another century. The one exception is Hesiod, who composed two extant poems, the Theogony and Works and Days, and possibly several others, including the Shield of Heracles and the Catalogue of Women. As we shall see, while Hesiodic poetry was not occupied specifically with heroic themes, it was part of the same formal tradition of epic, sharing with Homer key metrical, dialectal, and dictional features. -

Heroic Death in Ancient Greek Poetry and Art

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Classical Studies Faculty Research Classical Studies Department 2009 The Hero Beyond Himself: Heroic Death in Ancient Greek Poetry and Art Corinne Ondine Pache Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/class_faculty Part of the Classics Commons Repository Citation Pache, C.O. (2009). The hero beyond himself: Heroic death in ancient Greek poetry and art. In S. Albersmeier (Ed.), Heroes: Mortals and myths in ancient Greece (pp. 88-107). Walters Art Museum. This Contribution to Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Classical Studies Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classical Studies Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. In all those stories the hero is beyond himself into the next thing, be it those labors of Hercules, or Aeneas going into death. I thought the instant of the one humanness in Virgil's plan of it was that it was of course human enough to die, yet to come back, as he said, hoc opus, hie labor est. That was the Cumaean Sibyl speaking. This is Robert Creeley, and Virgil is dead now two thousand years, yet Hercules and the Aeneid, yet all that industrious wis- dom lives in the way the mountains and the desert are waiting for the heroes, and death also can still propose the old labors. -Robert Creeley, "Heroes" HEROISM AND DEATH The modern mind likes its heroism served with death. -

Minor Characters in the Aeneid Page 1

Minor Characters in the Aeneid Page 1 The following characters are described in the pages that follow the list. Page Order Alphabetical Order Aeolus 2 Achaemenides 8 Neptune 2 Achates 2 Achates 2 Aeolus 2 Ilioneus 2 Allecto 19 Cupid 2 Amata 17 Iopas 2 Andromache 8 Laocoon 2 Anna 9 Sinon 3 Arruns 22 Coroebus 3 Caieta 13 Priam 4 Camilla 22 Creusa 6 Celaeno 7 Helen 6 Coroebus 3 Celaeno 7 Creusa 6 Harpies 7 Cupid 2 Polydorus 7 Dēiphobus 11 Achaemenides 8 Drances 30 Andromache 8 Euryalus 27 Helenus 8 Evander 24 Anna 9 Harpies 7 Iarbas 10 Helen 6 Palinurus 10 Helenus 8 Dēiphobus 11 Iarbas 10 Marcellus 12 Ilioneus 2 Caieta 13 Iopas 2 Latinus 13 Juturna 31 Lavinia 15 Laocoon 2 Lavinium 15 Latinus 13 Amata 17 Lausus 20 Allecto 19 Lavinia 15 Mezentius 20 Lavinium 15 Lausus 20 Marcellus 12 Camilla 22 Mezentius 20 Arruns 22 Neptune 2 Evander 24 Nisus 27 Nisus 27 Palinurus 10 Euryalus 27 Polydorus 7 Drances 30 Priam 4 Juturna 31 Sinon 2 An outline of the ACL presentation is at the end of the handout. Minor Characters in the Aeneid Page 2 Aeolus – with Juno as minor god, less than Juno (tributary powers), cliens- patronus relationship; Juno as bargainer and what she offers. Both of them as rulers, in contrast with Neptune, Dido, Aeneas, Latinus, Evander, Mezentius, Turnus, Metabus, Ascanius, Acestes. Neptune – contrast as ruler with Aeolus; especially aposiopesis. Note following sympathy and importance of rhetoric and gravitas to control the people. Is the vir Aeneas (bringing civilization), Augustus (bringing order out of civil war), or Cato (actually -

Efi – Virgil and the World of the Hero

FROM TROY TO ROME: THE WORLD OF THE HERO IN VIRGIL’S AENEID Dr Efi Spentzou Royal Holloway, University of London [email protected] 1 A note on the translation A note on the text: the translation used in this presentation is by Robert Fagles for Penguin Classics. It is modern and vibrant and I hope you enjoy it! To create this free flow feel, and unlike other translations who try to adapt themselves so they are closer to the original line numberings, the lines in Fagles’ translation do not follow closely the lines in the original. So in order to make things easier for any of you who wish to look the text up in other translations or in the Latin text itself, I have given you the original text lines in the parenthesis. 2 Before Virgil… üAeneas mentioned in: Aeneas was only a minor figure in the ü Greek epic Iliad 20.307-8 narratives ü‘And now the might of Aeneas shall be lord over the Trojans and his sons’ sons, and those who are born of their seed hereafter.’ üHymn to Aphrodite 196-8 ü‘You will have a son of your own, who amongst the Trojans will rule, and children descended from him will never lack children themselves. His name will be Aeneas…’ 3 Aeneas: the Roman Achilles? v Aeneas = mythical and historical ◦ A figure more complicated than Achilles, carrying vHomeric hero (fight) Homeric, Hellenistic and v‘So let’s die, let’s rush to the thick Roman traits. of the fighting.’ (Aeneid 2) vHellenistic hero (emotion) v‘And I couldn’t believe I was bringing grief so intense, so painful to you.’ (Aeneas to Dido in Aeneid 6) vRoman hero (leadership) v‘You, who are Roman, recall how to govern mankind with your power.’ (Aeneid 6) 4 Book 1 The temple of Juno vThe strange sight of an ‘old’ and famous war: ◦ Aeneas now looking at ‘his’ ‘Here in this grove, a strange sight met his war from ‘the eyes and calmed his fears for the first time.