Beyond Modern & Postmodern Отвъд Модерното И

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulgarian Restaurant Chevermeto

EXHIBITIONS / Изложения January - June 2018 HELLO WINTER STORY Health and Sport FESTIVAL Здраве и спорт 20 - 21.01. International Tourist Fair HOLIDAY & SPA EXPO Международна туристическа борса 14 - 16.02. LUXURY WEDDINGS Wedding and Events Industry EXPO Сватбена и събитийна индустрия 23 - 25.02. BULGARIA BUILDING Building Materials and Machines WEEK Строителни материали и машини 07 - 10.03. Safety&Security SECURITY EXPO Цялостни решения за сигурност и безопасност 07 - 10.03. GRAND CHOCOLATE Chocolate and Chocolate Products FESTIVAL Шоколад и шоколадови продукти 10 - 11.03. BEBEMANIA – Baby and Kids Products SHOPPING Всичко за бъдещите и настоящи родители 16 - 18.03. VOLKSWAGEN CLUB Event for the Fans of the Brand FEST Събитие за феновете на марката 17 - 18.03. Machinery, Industrial Equipment and Innovative MACHTECH & Technologies INNOTECH EXPO Индустриални машини, оборудване 26- 29.03. и иновационни технологии Water and Water Management WATER SOFIA Води и воден мениджмънт 27 - 29.03. Woodworking and Furniture Industry TECHNOMEBEL Дървообработваща и мебелна промишленост 24 - 28.04. WORLD OF Furniture, Interior textile and home accessories Обзавеждане, интериорен текстил 24 - 28.04. FURNITURE и аксесоари за дома BULMEDICA / Medical and Dental Industry BULDENTAL Медицина 16 - 18.05. September - December 2018 HUNTING, FISHING, Hunting and Sport Weapons, Fishing Accessories, Sport Ловни и с портни оръжия, риболовни 27 - 30.09. SPORT принадлежности, спорт Communication Art, Print, Image, Sign COPI’S Рекламни и печатни комуникации 02 - 04.10. Aesthetics, Cosmetics, SPA, Health, Hair, ARENA OF BEAUTY Nail, Mackeup 05 - 07.10. Форум за здраве, красота и естетика Baby and Kids Products BEBEMANIA Всичко за бъдещите и настоящи родители 19 - 21.10. -

Zornitsa Markova the KTB STATE

Zornitsa Markova THE KTB STATE Sofia, 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or express written consent from Iztok-Zapad Publishing House. transmitted in any form or by any means without first obtaining © Zornitsa Markova, 2017 © Iztok-Zapad Publishing House, 2017 ISBN 978-619-01-0094-2 zornitsa markova THE KTB STATE CHRONICLE OF THE LARGEST BANK FAILURE IN BULGARIA — THE WORKINGS OF A CAPTURED STATE THAT SOLD OUT THE PUBLIC INTEREST FOR PRIVATE EXPEDIENCY CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS / 12 EDITOR’S FOREWORD / 13 SUMMARY / 15 READER’S GUIDE TO THE INVESTIGATION / 21 1. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND / 23 DEVELOPMENTS IN THE BULGARIAN BANKING SECTOR THAT PRE-DATE KTB ..........................................................25 Headed for a Banking Crisis .................................................................................................. 26 Scores of Banks Close Their Doors................................................................................... 29 First Private Bank — Backed by the Powerful, Favoured by the Government ......................................................... 33 Criminal Syndicates and Their Banks — the Birth of a State within the State ...........................................................................35 A Post-Crisis Change of Players ..........................................................................................37 A FRESH START FOR THE FLEDGLING KTB ..................................................... 40 KTB SALE ..........................................................................................................................................42 -

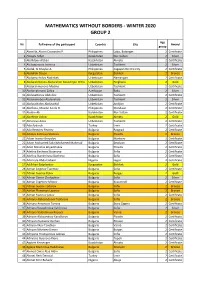

Mathematics Without Borders - Winter 2020 Group 2

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - WINTER 2020 GROUP 2 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abanilla, Alaina Cassandra P. Philippines Lobo, Batangas 2 Certificate 2 Abayev Aidyn Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 2 Silver 3 Abdildaev Alzhan Kazakhstan Almaty 2 Certificate 4 Abduazimova Jasmina Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Silver 5 Abdul, Al Khaylar A. Philippines Cagayan De Oro City 2 Certificate 6 Abdullah Dayan Kyrgyzstan Bishkek 2 Bronze 7 Abdumazhidov Nodirbek Uzbekistan Namangan 2 Certificate 8 Abdurahmonov Abdurahim Boxodirjon O'G'Li Uzbekistan Ferghana 2 Gold 9 Abdurahmonova Madina Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 10 Abdurrahmanli Zahra Azerbaijan Baku 2 Silver 11 Abdusattorov Abdullox Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 12 Abduvahobov Abduvahob Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Silver 13 Abduvohidov Abduvohid Uzbekistan Andijon 2 Certificate 14 Abellana, Maxine Anela O. Philippines Mandaue 2 Certificate 15 Abildin Ali Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 2 Certificate 16 Abirkhan Adina Kazakhstan Almaty 2 Gold 17 Abrorova Aziza Uzbekistan Tashkent 2 Certificate 18 Ada Aydınok Turkey Izmir 2 Certificate 19 Ada Remziev Fevziev Bulgaria Razgrad 2 Certificate 20 Adaliya Kalinova Stoilova Bulgaria Plovdiv 2 Bronze 21 Adam Ivanov Goryalov Bulgaria Markovo 2 Certificate 22 Adam Mohamed Sabri Mohamed Mahmud Bulgaria Smolyan 2 Certificate 23 Adeli Nikolova Boyadzhieva Bulgaria Plovdiv 2 Certificate 24 Adelina Encheva Stoianova Bulgaria Sofia 2 Certificate 25 Adelina Stanimirova Docheva Bulgaria Sofia 2 Certificate 26 Adenrele Abdul Jabaar Nigeria Lagos 2 Certificate -

Annual Report 2018

Annual Report 2018 Bulgaria 2 FINLAN D NO RWAY Helsinki Oslo Stockholm Tallinn BALT IC SEA ESTO NIA SWEDEN Riga LATVIA DENMAR K Moscow NORTH SEA Co penhagen LITHUANIA RUSSIA Vilnius Minsk RUSSIA Dublin IRELAND BELARUS UNITED KINGDOM Amsterdam Berlin POLAN D Warsaw Lo ndon NETHERLANDS G ERMA NY BELG IUM Brussels Frankfurt Kiev Prague LUXEMBOURG UKRAINE CZECH RE PUBLIC Paris SLOVAKIA KA ZAKHSTAN Vienna Bratislava MOLDOVA SWITZERLAN D AUSTRIA Budapest Chisinau FRANCE Bern LIECHTEN - STEIN Ma ribor HUNGARY SLOVENIA ROMA NIA Zagreb CR OA TI A ARAL Belgrade SEA BOSNIA AND SERBIA Bucha rest HERZ EGOWINA Sarajevo Pristina C UZBEKISTAN ITALY MONTEN EGRO Soa BLACK SEA ASPIAN KOSOVO Co rsica Podgorica BULG ARI A Skopje GEORGIA Rome Tbilisi Tirana MACEDONIA Istanbul PORTUGAL Madrid ALBANIA ARME NIA Baku Sardinia Yerevan ASERBAIJAN SE Lisbon GREECE Ankara A TURKMENISTA N SPAIN Athens TURKE Y Asgabat MEDITERRANEAN SEA Sicily Tunis Algiers IRAN SYRI A IRAQ Tehran ALGERIA TUNISIA MOROCCO CYPRUS Nico sia www.rbinternational.com HEAD OFFICE AND NE TW ORK BANKS BRANCHES, REPRESENTATIVE OFFICES AN D OTHER UNITS 3 FINLAN D NO RWAY Helsinki Oslo Stockholm Tallinn BALT IC SEA ESTO NIA SWEDEN Riga LATVIA DENMAR K Moscow NORTH SEA Co penhagen LITHUANIA RUSSIA Vilnius Minsk RUSSIA Dublin IRELAND BELARUS UNITED KINGDOM Amsterdam Berlin POLAN D Warsaw Lo ndon NETHERLANDS G ERMA NY BELG IUM Brussels Frankfurt Kiev Prague LUXEMBOURG UKRAINE CZECH RE PUBLIC Paris SLOVAKIA KA ZAKHSTAN Vienna Bratislava MOLDOVA SWITZERLAN D AUSTRIA Budapest Chisinau FRANCE Bern LIECHTEN -

Momowo · 100 Works in 100 Years: European Women in Architecture

MoMoWo · 100 WORKS IN 100 YEARS 100 WORKS IN YEARS EUROPEAN WOMEN IN ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN · 1918-2018 · MoMoWo ISBN 978-961-254-922-0 9 789612 549220 not for sale 1918-2018 · DESIGN AND ARCHITECTURE IN WOMEN EUROPEAN Ljubljana - Torino MoMoWo . 100 Works in 100 Years European Women in Architecture and Design . 1918-2018 Edited by Ana María FERNÁNDEZ GARCÍA, Caterina FRANCHINI, Emilia GARDA, Helena SERAŽIN MoMoWo Scientific Committee: POLITO (Turin | Italy) Emilia GARDA, Caterina FRANCHINI IADE-U (Lisbon | Portugal) Maria Helena SOUTO UNIOVI (Oviedo | Spain) Ana Mária FERNÁNDEZ GARCÍA LU (Leiden | The Netherlands) Marjan GROOT ZRC SAZU (Ljubljana | Slovenia) Helena SERAŽIN UGA (Grenoble | France) Alain BONNET SiTI (Turin | Italy) Sara LEVI SACERDOTTI English language editing by Marta Correas Celorio, Alberto Fernández Costales, Elizabeth Smith Grimes Design and layout by Andrea Furlan ZRC SAZU, Žiga Okorn Published by France Stele Institute of Art History ZRC SAZU, represented by Barbara Murovec Issued by Založba ZRC, represented by Oto Luthar Printed by Agit Mariogros, Beinasco (TO) First edition / first print run: 3000 Ljubljana and Turin 2016 © 2016, MoMoWo © 2016, Založba ZRC, ZRC SAZU, Ljubljana http://www.momowo.eu Publication of the project MoMoWo - Women’s Creativity since the Modern Movement This project has been co-funded 50% by the Creative Europe Programme of the European Commission This publication reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. This book was published on the occasion of the MoMoWo traveling exhibition MoMoWo · 100 Works in 100 Years · European Women in Architecture and Design · 1918-2018, which was first presented at the University of Oviedo Historical Building, Spain, from 1 July until 31 July 2016. -

България Bulgaria Държава Darzhava

Проект "Разбираема България" Вид Транслитера Собствено име Транслитерация на собственото име Вид обект Транслитерация Местоположение Транслитерация местоположение ция България Bulgaria държава darzhava Абаджиев Abadzhiev фамилно име familno ime Абаджийска Abadzhiyska улица ulitsa Сливен Sliven град grad Абаносов Abanosov фамилно име familno ime Абдовица Abdovitsa квартал kvartal София Sofia град grad Абланица Ablanitsa село selo Абланов Ablanov фамилно име familno ime Абланово Ablanovo улица ulitsa Сливен Sliven град grad Абланово Ablanovo улица ulitsa Ямбол Yambol град grad Аблановска низина Ablanovska nizina низина nizina Абоба Aboba улица ulitsa Бургас Burgas град grad Абоба Aboba улица ulitsa Разград Razgrad град grad Абоба Aboba улица ulitsa София Sofia град grad Абрашев Abrashev фамилно име familno ime Абрашков Abrashkov фамилно име familno ime Абрит Abrit село selo Абритус Abritus улица ulitsa Разград Razgrad град grad Ав. Гачев Av. Gachev улица ulitsa Габрово Gabrovo град grad Ав. Митев Av. Mitev улица ulitsa Враца Vratsa град grad Ав. Стоянов Av. Stoyanov улица ulitsa Варна Varna град grad Аваков Avakov фамилно име familno ime Авгостин Avgostin лично име lichno ime Август Avgust лично име lichno ime Август Попов Avgust Popov улица ulitsa Шумен Shumen град grad Августа Avgusta лично име lichno ime Августин Avgustin лично име lichno ime Августина Avgustina лично име lichno ime Авджиев Avdzhiev фамилно име familno ime Аверкий Averkiy улица ulitsa Кюстендил Kyustendil град grad Авксентий Велешки Avksentiy Veleshki улица ulitsa Варна -

Regatul Romaniei

RegatulRomaniei file:///C:/Programele%20Mele/IstorieRomania1/RegatulRomaniei/Regat... Regatul României Visul unirii tuturor românilor sub un singur steag a frământat mințile conducătorilor încă din cele mai vechi timpuri, dar alianțele militare și interesele de ordin comercial nu au fost în favoarea simplificării relațiilor dintre diferitele formațiuni statale. În vechime, țările românești au negociat protecția celor două mari imperii ale romanilor, apoi începând cu secolul al XIII-lea au întreținut legături de prietenie și ajutor mutual cu Polonia și Lituania. Din secolul al XV-lea, ca state vasale Imperiului Otoman dar sub protecția directă a Hanatului Crimeei, s-a pus problema formării unui eyalat turcesc comun. Proiectul a fost însă refuzat cu dârzenie, ca urmare a divergențelor de ordin religios. Ca o soluție de compromis, sultanii au permis independența religioasă a celor trei principate, în schimbul dependenței economice. Situația de criză a intervenit o dată cu revoluția și apoi războiul de independență purtat de greci și sârbi. Sub aripa ocrotitoare a Bisericii Ortodoxe Răsăritene, creștinii din toate țările Balcanice au ridicat la început glasul, apoi armele, cerând vehement ieșirea din situația de compromis religios. Ca rezultat, boierii și dragomanii greci au fost maziliți, iar mănăstirile filiale ale celor de la Muntele Athos au fost secularizate. În urma grecilor au rămas nenumăratele lor rude născute din alianțe cu casele boierești autohtone, practic aproape toată crema boierimii. Pentru a umple vidul administrativ rămas s-a hotărât instituirea unei locotenențe domnești, ajutată de o Adunare Constituantă a fruntașilor celor două țări. În ambele principate, toate sufragiile au fost întrunite în anul 1859 de Colonelul Alexandru Ioan Cuza, cu funcția de Ministru de Război, fost deputat de Galați și fost șef al Miliției de la Dunărea de Jos. -

Winter21-Group4

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS ‐ WINTER 2021 GROUP 4 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abdildin Amangeldy Kazakhstan Balkhash 4 Certificate 2 Abdiyev Amir Akmalevich Uzbekistan Fergana 4 Gold 3 Abdubannopov Behruzbek Behzodjon ugli Uzbekistan Fergana 4 Certificate 4 Abdukhakimov Firdavsbek Ulugbek ugli Uzbekistan Fergana 4 Certificate 5 ABDUL AAHAD HUSSAIN NIGERIA ABUJA 4 Certificate 6 Abdullaev Ulugbek Timur ugli Uzbekistan Fergana 4 Certificate 7 Abdullayeva Rumayso Alisher qizi Uzbekistan Fergana 4 Certificate 8 Abdullyaev Imronjon Inomjon ugli Uzbekistan Fergana 4 Gold 9 Adalia Miroslavova Hristova Bulgaria Burgas, Sarafovo 4 Bronze 10 Adelina Boykova Traykova Bulgaria Blagoevgrad 4 Certificate 11 Adelina Denislavova Atanasova Bulgaria Varna 4 Certificate 12 Adelina Radostinova Grozeva Bulgaria Varna 4 Bronze 13 Adem Fikret Adil Bulgaria Aytos 4 Bronze 14 Adil Ahmad Fazli Afghanistan Kandahar 4 Certificate 15 Adreana Andreanova Georgieva Bulgaria Varna 4 Certificate 16 Adriana Angelova Sotirova Bulgaria Sofia 4 Silver 17 Adriana Dimitrova Georgieva Bulgaria Burgas 4 Bronze 18 Adriana Ivanova Petkova Bulgaria Burgas 4 Bronze 19 Adriana Stefanova Tamahkyarova Bulgaria Sofia 4 Certificate 20 Adriyan Hristov Yabanozov Bulgaria Ruse 4 Certificate 21 Ahmadzhanov Xozhiakbar Uzbekistan Namangan 4 Certificate 22 Ahsanullah Popalzai Afghanistan Kandahar 4 Certificate 23 Akat Azima Kazakhstan Taldykorgan 4 Gold 24 Akish Yerdar Kazakhstan Almaty 4 Certificate 25 Akopdjanov Georgy Mikhaylovich Uzbekistan Fergana 4 Bronze -

Industry Report Architectural and Engineering Activities; Technical Testing and Analysis 2017 BULGARIA

Industry Report Architectural and engineering activities; technical testing and analysis 2017 BULGARIA seenews.com/reports This industry report is part of your subcription access to SeeNews | seenews.com/subscription CONTENTS I. KEY INDICATORS II. INTRODUCTION III. REVENUES IV. EXPENSES V. PROFITABILITY VI. EMPLOYMENT 1 SeeNews Industry Report In 2016 there were a total of 9,246 companies operating in I. KEY INDICATORS the industry. In 2015 their number totalled 9,173. The Architectural and engineering activities; technical NUMBER OF COMPANIES IN ARCHITECTURAL AND ENGINEERING testing and analysis industry in Bulgaria was represented by ACTIVITIES; TECHNICAL TESTING AND ANALYSIS INDUSTRY BY 8,898 companies at the end of 2017, compared to 9,246 in SECTORS the previous year and 9,173 in 2015. SECTOR 2017 2016 2015 ENGINEERING ACTIVITIES AND RELATED 5,770 6,070 5,997 The industry's net profit amounted to BGN 103,174,000 in TECHNICAL CONSULTANCY 2017. ARCHITECTURAL ACTIVITIES 2,323 2,355 2,352 TECHNICAL TESTING AND ANALYSIS 805 821 824 The industry's total revenue was BGN 1,366,322,000 in 2017, down by 4.68% compared to the previous year. The combined costs of the companies in the Architectural and engineering activities; technical testing and analysis III. REVENUES industry reached BGN 1,234,117,000 in 2017, up by 4.96% year-on-year. The total revenue in the industry was BGN 1,366,322,000 in 2017, BGN 1,433,434,000 in 2016 and 1,731,089,000 in 2015. The industry's total revenue makes up 1.42% to the country's Gross domestic product (GDP) in 2017, compared Total revenue to 1.55% for 2016 and 1.94% in 2015. -

Industry Report Other Personal Service Activities 2018 BULGARIA

Industry Report Other personal service activities 2018 BULGARIA seenews.com/reports This industry report is part of your subcription access to SeeNews | seenews.com/subscription CONTENTS I. KEY INDICATORS II. INTRODUCTION III. REVENUES IV. EXPENSES V. PROFITABILITY VI. EMPLOYMENT 1 SeeNews Industry Report NUMBER OF COMPANIES IN OTHER PERSONAL SERVICE I. KEY INDICATORS ACTIVITIES INDUSTRY BY SECTORS SECTOR 2018 2017 2016 The Other personal service activities industry in Bulgaria HAIRDRESSING AND OTHER BEAUTY 11,087 10,271 9,803 was represented by 18,979 companies at the end of 2018, TREATMENT compared to 17,610 in the previous year and 16,830 in OTHER PERSONAL SERVICE ACTIVITIES N.E.C. 6,330 5,823 5,589 2016. PHYSICAL WELL-BEING ACTIVITIES 535 506 469 WASHING AND (DRY-)CLEANING OF TEXTILE 522 518 507 The industry's net profit amounted to BGN 101,792,000 in AND FUR PRODUCTS 2018. FUNERAL AND RELATED ACTIVITIES 505 492 462 The industry's total revenue was BGN 707,489,000 in 2018, up by 28.28% compared to the previous year. III. REVENUES The combined costs of the companies in the Other personal service activities industry reached BGN The total revenue in the industry was BGN 707,489,000 in 598,653,000 in 2018, up by 30.04% year-on-year. 2018, BGN 551,511,000 in 2017 and 444,556,000 in 2016. The industry's total revenue makes up 0.71% to the country's Gross domestic product (GDP) in 2018, compared Total revenue to 0.57% for 2017 and 0.48% in 2016. -

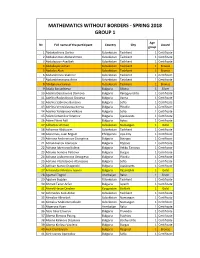

Mathematics Without Borders - Spring 2018 Group 1

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - SPRING 2018 GROUP 1 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abdukadirova Darina Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 2 Abdukarimov Abdurahmon Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 3 Abdulazizov Asadbek Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 4 Abdullayev Adnan Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Bronze 5 Abdulov Alan Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Bronze 6 Abdurahimov Shahrier Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 7 Abdurakhmanova Aziza Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 8 Abidjanova Sureya Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Bronze 9 Adalia Barutchieva Bulgaria Silistra 1 Silver 10 Adelina Desislavova Dankova Bulgaria Panagyurishte 1 Certificate 11 Adelina Radostinova Grozeva Bulgaria Varna 1 Certificate 12 Adelina Sabinova Borisova Bulgaria Sofia 1 Certificate 13 Adelina Ventsislavova Koeva Bulgaria Plovdiv 1 Certificate 14 Adelina Yordanova Velkova Bulgaria Sofia 1 Certificate 15 Adem Dzhemilov Ademov Bulgaria Lyaskovets 1 Certificate 16 Adem Fikret Adil Bulgaria Aytos 1 Certificate 17 Adhamov Ahmad Uzbekistan Namangan 1 Gold 18 Adkamov Abduazim Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 19 Adoremos, Juan Miguel Philippines Lipa City 1 Certificate 20 Adreana Andreanova Georgieva Bulgaria Bourgas 1 Certificate 21 Adrian Ivanov Atanasov Bulgaria Popovo 1 Certificate 22 Adriana Iskrenova Koleva Bulgaria Veliko Tarnovo 1 Certificate 23 Adriana Ivanova Petkova Bulgaria Burgas 1 Certificate 24 Adriana Lyubomirova Georgieva Bulgaria Plovdiv 1 Certificate 25 Adriana Vladislavova Atanasova Bulgaria Sofia 1 Certificate 26 Adriyan Ivanov Draganski Bulgaria -

Софийски Сюжети Sofia Themes © Редактор / Editor Веселина Филипова / Vesselina Filipova

65 години АБУЖЕТ Софийски сюжети 65 years ABUJET Sofia themes ABUJET Корица /Cover: Централна минерална баня/ Central mineral bath Фотограф/ Photograph: Донко Филипов / Donko Filipov Четвърта корица / Fourth cover: Централен военен клуб / Central Military Club Фотограф/ Photograph: Веселина Филипова / Vesselina Filipova С подкрепата на Столична община With the support of Sofia Municipality Софийски сюжети Sofia themes © Редактор / Editor Веселина Филипова / Vesselina Filipova © Автори / Authors: Антоанета Титянова / Antoaneta Tityanova Бойка Асиова / Boyka Asiova Бойка Велинова / Boyka Velinova Веселина Филипова / Vesselina Filipova Магдалена Гигова / Magdalena Gigova Мария Мира Христова/ Maria Mira Hristova Мария Петкова / Maria Petkova Оля Ал-Ахмед / Olya Al-Ahmed Славяна Манолова / Slavyana Manolova Соня Алексиева / Sonya Aleksieva Юлия Вълкова / Julia Valkova © Превод / Translation: Агенция „ПРЕВОДИ БГ“ / PREVODI BG Translation Agency © Графичен дизайн / Graphic design: Лиляна Дилова / Liliyana Dilova © Фотографии / Photographs: Авторите / The authors © Издател: ABUJET, 2021 ISBN 978-954-92596-9-8 Съдържание / Content Веселина Филипова / Vesselina Filipova............................................................ 7 Предговор / Preface Пламен Старев / Plamen Starev...................................................................... 8 65 години АБУЖЕТ – клубът на разказвачите на истории 65 years ABUJET – the storytellers’ club Антоанета Титянова / Antoaneta Tityanova................................................... 10 За чудото