Teaching Artistry of the Flute: a Summary of Dissertation Recitals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dynamicsanddissonance: Theimpliedharmonictheoryof

Intégral 30 (2016) pp. 67–80 Dynamics and Dissonance: The Implied Harmonic Theory of J. J. Quantz by Evan Jones Abstract. Chapter 17, Section 6 of Quantz’s Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte traver- siere zu spielen (1752) includes a short original composition entitled “Affettuoso di molto.” This piece features an unprecedented variety of dynamic markings, alternat- ing abruptly from loud to soft extremes and utilizing every intermediate gradation. Quantz’s discussion of this example provides an analytic context for the dynamic markings in the score: specific levels of relative amplitude are prescribed for particu- lar classes of harmonic events, depending on their relative dissonance. Quantz’s cat- egories anticipate Kirnberger’s distinction between essential and nonessential dis- sonance and closely coincide with even later conceptions as indicated by the various chords’ spans on the Oettingen–Riemann Tonnetz and on David Temperley’s “line of fifths.” The discovery of a striking degree of agreement between Quantz’s prescrip- tions for performance and more recent theoretical models offers a valuable perspec- tive on eighteenth-century musical intuitions and suggests that today’s intuitions might not be very different. Keywords and phrases: Quantz, Versuch, Affettuoso di molto, thoroughbass, disso- nance, dynamics, Kirnberger, Temperley, line of fifths, Tonnetz. 1. Dynamic Markings in Quantz’s ing. Like similarly conceived publications by C. P. E. Bach, “Affettuoso di molto” Leopold Mozart, and others, however, Quantz’s treatise en- gages -

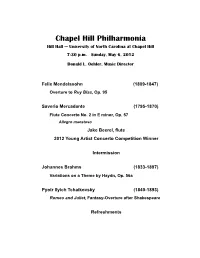

Concert Program

Chapel Hill Philharmonia Hill Hall — University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 7:30 p.m. Sunday, May 6, 2012 Donald L. Oehler, Music Director Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) Overture to Ruy Blas, Op. 95 Saverio Mercadante (1795-1870) Flute Concerto No. 2 in E minor, Op. 57 Allegro maestoso Jake Beerel, flute 2012 Young Artist Concerto Competition Winner Intermission Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Variations on a Theme by Haydn, Op. 56a Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) Romeo and Juliet, Fantasy-Overture after Shakespeare Refreshments Inspirations William Shakespeare conveyed the overwhelming impact of Julius Caesar in imperial Rome: “Why, man, he doth bestride the narrow world like a Colussus.” So might 19th century composers have viewed the figure of Ludwig van Beethoven. With his Symphony No. 3, known as Eroica, composed in 1803, Beethoven radically altered the evolution of symphonic music. The work was inspired by Napoléon Bonaparte’s republican ideals while rejecting that ‘hero’s’ assumption of an imperial mantle. Beethoven broke precedent by employing his art “as a vehicle to convey beliefs,” expanding beyond compositional technique to add the “dimension of meaning and interpretation. All the more remarkable…the high priest of absolute music, effected this change.” (composer W.A. DeWitt) Beethoven, in a word, brought Romanticism to the concert hall, “replac[ing] the Enlightenment cult of reason with a cult of instinct, passion, and the creative genius as virtual demigod. The Romantics seized upon Beethoven’s emotionalism, his sense of the individual as hero.” (composer/writer Jan Swafford) The expression of this new sensibility took many forms, ranging from intensified expression within classical forms, exemplified by Felix Mendelssohn or Johannes Brahms, to the unbridled fervor of Piyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, the revolutionary virtuosity and structural innovations of Franz Liszt, the hallucinatory visions of Hector Berlioz, and the megalomania of Richard Wagner. -

Eric Mandat's Chips Off the Ol' Block

California State University, Northridge FLUTTER, SWING, AND SQUAWK: ERIC MANDAT’S CHIPS OFF THE OL’ BLOCK A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Music in Performance By Nicole Irene Moran December 2012 Thesis of Nicole Irene Moran is approved: ___________________________________ ___________________ Dr. Lawrence Stoffel Date ___________________________________ ___________________ Professor Mary Schliff Date ___________________________________ ___________________ Dr. Julia Heinen, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Dedicated to: Robert Paul Moran (12/13/39- 8/6/11) iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ii Dedication iii Abstract v FLUTTER, SWING, AND SQUAWK: ERIC MANDAT’S CHIPS OFF THE OL’ BLOCK 1 Recital Program 26 Bibliography 27 iv ABSTRACT FLUTTER, SWING, AND SQUAWK: ERIC MANDAT’S CHIPS OFF THE OL’ BLOCK By Nicole Irene Moran Master of Music in Performance The bass clarinet first appeared in the music world as a supportive instrument in orchestras, wind ensembles and military bands, but thanks to Giuseppe Saverio Raffaele Mercadante’s opera Emma d'Antiochia (1834), the bass clarinet began to embody the role of a soloist. Important passages in orchestral works such as Strauss’ Don Quixote (1898) and Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring (1913) further advanced the perception of the bass clarinet as a solo instrument, and beginning in the 1970’s, composers such as Harry Sparnaay and Brian Ferneyhough began writing solo works for unaccompanied bass clarinet. In the twenty-first century, clarinet virtuoso and composer Eric Mandat experiments with the capabilities of the bass clarinet in his piece Chips Off the Ol’ Block, utilizing enormous registral leaps, techniques such as multiphonics and quarter-tone fingerings, as well as incorporating jazz-inspired rhythms into the music. -

Saverio MERCADANTE

SAVERIOMERCADANTE Flute Concertos Nos. 1, 2 and 4 Patrick Gallois, Flute and Conductor Sinfonia Finlandia Jyväskylä Saverio Mercadante (1795-1870): here, not only in the Largo, but also at various points in the which the soloist plays from the start, in the first of no fewer faster movements either side of it, providing an effective than five entries, one of which (the second) introduces a new Flute Concertos Nos. 1, 2 and 4 contrast to the more acrobatic writing and brighter rhythms. In theme and another (the fourth) sees a modulation to the Saverio Mercadante was born in 1795 in the southern Italian 18) and a trio for flute, violin and guitar (1816). The young the Allegro maestoso, the most demanding of the movements minor. These five sections alternate with four brief orchestral town of Altamura. Between 1808 and 1819 he studied the composer’s interest in the flute, an instrument which at that from a formal point of view, orchestral interludes separate interludes, reduced in both scale and significance. violin, cello, bassoon, clarinet and flute, as well as composition time had yet to be fully technically developed, stemmed three substantial passages in which the soloist is called on The title-page of the Flute Concerto No. 1, Op. 49, (under Giovanni Furno, Giacomo Tritto and Nicola Zingarelli), from his everyday life at the conservatory, where he was to play all kinds of embellishments, high-speed passages gives both its date of composition, 1813, and the name of its at the conservatory of Naples, then known as the Royal mixing with virtuoso teachers and fellow students – the best (including octave leaps, extended chromatic passages, dedicatee, Mercadante’s fellow student Pasquale Buongiorno, College of Music. -

Im Doppler-Affekt

Magazin der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien April 2013 Im Doppler-Affekt Eine philharmonische „Doppleriade“ mit Walter Auer und Karl-Heinz Schütz Franz und Karl Doppler: Im 19. Jahrhundert galten die beiden Brüder und Mitglieder der Wiener Philharmoniker als die Flötisten schlechthin. Walter Auer und Karl-Heinz Schütz, philharmonische Soloflötisten der Jetztzeit, widmen ihren Vorgängern einen Abend im Gläsernen Saal. Wem sind sie heute noch geläufig, die Namen der vielen virtuosen Pioniere des sich im 19. Jahrhundert institutionalisierenden öffentlichen Musiklebens? Wer weiß sie noch zu würdigen, jene stupenden Musiker, die durch ihre gewinnende Umtriebigkeit das Fundament für den modernen Konzertbetrieb legten, sich als verdienstvolle Pädagogen hervortaten und nebenbei die Spieltechniken ihrer jeweiligen Instrumente revolutionierten? Natürlich haben sich Niccolò Paganini, Frédéric Chopin und Franz Liszt unauslöschlich in die Musikgeschichte eingeschrieben. Aber wie steht es um die Klarinettisten Baermann und Hermstedt, die Cellisten Romberg, Dotzauer und Popper oder die Flötistenbrüder Franz und Karl Doppler? Ihre effektvollen Kompositionen werden heute zumeist nur noch bei Vortragsabenden des musikalischen Nachwuchses von Tanten und Großeltern beklatscht. So manchen Eltern und Nachbarn sollen die gefälligen Kantilenen und Läufe, abhängig von der jeweiligen Übeintensität, dagegen schon zu Kopf gestiegen sein … Wunderkinder an der Flöte Den Flötisten Franz und Karl Doppler wird nun im Musikverein die seltene Ehre zuteil, dem Milieu der Vortragsabende entrissen und von zwei Meistern ihres Fachs abendfüllend im besten Licht präsentiert zu werden. Walter Auer und Karl-Heinz Schütz, Soloflötisten an der Wiener Staatsoper und bei den Philharmonikern, nehmen den 130. Todestag von Franz, dem Älteren der beiden, zum Anlass, auf die Vielseitigkeit der sehr oft im Doppel in Erscheinung tretenden Brüder hinzuweisen. -

MWV Saverio Mercadante

MWV Saverio Mercadante - Systematisches Verzeichis seiner Werke vorgelegt von Michael Wittmann Berlin MW-Musikverlag Berlin 2020 „...dem Andenken meiner Mutter“ November 2020 © MW- Musikverlag © Michael Wittmann Alle Rechte vorbehalten, insbesondere die des Nachdruckes und der Übersetzung. !hne schriftliche Genehmigung des $erlages ist es auch nicht gestattet, dieses urheberrechtlich geschützte Werk oder &eile daraus in einem fototechnischen oder sonstige Reproduktionverfahren zu verviel"(ltigen oder zu verbreiten. Musikverlag Michael Wittmann #rainauerstraße 16 ,-10 777 Berlin /hone +049-30-21*-222 Mail4 m5 musikverlag@gmail com Vorwort In diesem 8ahr gedenkt die Musikwelt des hundertfünzigsten &odestages 9averio Merca- dantes ,er Autor dieser :eilen nimmt dies zum Anlaß, ein Systematisches Verzeichnis der Wer- ke Saverio Mercdantes vorzulegen, nachdem er vor einigen 8ahren schon ein summarisches Werkverzeichnis veröffentlicht hat <Artikel Saverio Mercadante in: The New Groves ictionary of Musik 2000 und erweitert in: Neue MGG 2008). ?s verbindet sich damit die @offnung, die 5eitere musikwissenschaftliche ?rforschung dieses Aomponisten zu befördern und auf eine solide philologische Grundlage zu stellen. $orliegendes $erzeichnis beruht auf einer Aus5ertung aller derzeit zugänglichen biblio- graphischen Bindmittel ?in Anspruch auf $ollst(ndigkeit 5(re vermessen bei einem Aom- ponisten 5ie 9averio Mercadante, der zu den scha"fensfreudigsten Meistern des *2 8ahrhunderts gehört hat Auch in :ukunft ist damit zu rechnen, da) 5eiter Abschriften oder bislang unbekannte Werke im Antiquariatshandel auftauchen oder im :uge der fortschreitenden Aata- logisierung kleinerer Bibliotheken aufgefunden 5erden. #leichwohl dürfte (mit Ausnahme des nicht vollst(ndig überlieferten Brüh5erks> mit dem Detzigen Borschungsstand der größte &eil seiner Werk greifbar sein. ,ie Begründung dieser Annahme ergibt sich aus den spezi"ischen #egebenheiten der Mercadante-Überlieferung4 abgesehen von der frühen Aonservatoriumszeit ist Mercdante sehr sorgfältig mit seinen Manuskripten umgegangen. -

An Historical and Analytical Study of Renaissance Music for the Recorder and Its Influence on the Later Repertoire Vanessa Woodhill University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1986 An historical and analytical study of Renaissance music for the recorder and its influence on the later repertoire Vanessa Woodhill University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Woodhill, Vanessa, An historical and analytical study of Renaissance music for the recorder and its influence on the later repertoire, Master of Arts thesis, School of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1986. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/2179 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] AN HISTORICAL AND ANALYTICAL STUDY OF RENAISSANCE MUSIC FOR THE RECORDER AND ITS INFLUENCE ON THE LATER REPERTOIRE by VANESSA WOODHILL. B.Sc. L.T.C.L (Teachers). F.T.C.L A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the School of Creative Arts in the University of Wollongong. "u»«viRsmr •*"! This thesis is submitted in accordance with the regulations of the University of Wotlongong in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. I hereby certify that the work embodied in this thesis is the result of original research and has not been submitted for a higher degree at any other University or similar institution. Copyright for the extracts of musical works contained in this thesis subsists with a variety of publishers and individuals. Further copying or publishing of this thesis may require the permission of copyright owners. Signed SUMMARY The material in this thesis approaches Renaissance music in relation to the recorder player in three ways. -

Johann Joachim Quantz

Johann Joachim Quantz Portrait by an unknown 18th-century artist An account of his life taken largely from his autobiography published in 1754–5 Greg Dikmans Johann Joachim Quantz (1697–1773) Quantz was a flute player and composer at royal courts, writer on music and flute maker, and one of the most famous musicians of his day. His autobiography, published in F.W. Marpurg’s Historisch-kritische Beyträge (1754– 5), is the principal source of information on his life. It briefly describes his early years and then focuses on his activities in Dresden (1716–41), his Grand Tour (1724– 27) and his work at the court of Frederick the Great in Berlin and Potsdam (from 1741). Quantz was born in the village Oberscheden in the province of Hannover (northwestern Germany) on 30 January 1697. His father was a blacksmith. At the age of 11, after being orphaned, he began an apprenticeship (1708–13) with his uncle Justus Quantz, a town musician in Merseburg. Quantz writes: I wanted to be nothing but a musician. In August … I went to Merseburg to begin my apprenticeship with the former town-musician, Justus Quantz. … The first instrument which I had to learn was the violin, for which I also seemed to have the greatest liking and ability. Thereon followed the oboe and the trumpet. During my years as an apprentice I worked hardest on these three instruments. Merseburg Matthäus Merian While still an apprentice Quantz also arranged to have keyboard lessons: (1593–1650) Due to my own choosing, I took some lessons at this time on the clavier, which I was not required to learn, from a relative of mine, the organist Kiesewetter. -

Schiller and Music COLLEGE of ARTS and SCIENCES Imunci Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures

Schiller and Music COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ImUNCI Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures From 1949 to 2004, UNC Press and the UNC Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures published the UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures series. Monographs, anthologies, and critical editions in the series covered an array of topics including medieval and modern literature, theater, linguistics, philology, onomastics, and the history of ideas. Through the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, books in the series have been reissued in new paperback and open access digital editions. For a complete list of books visit www.uncpress.org. Schiller and Music r.m. longyear UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures Number 54 Copyright © 1966 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons cc by-nc-nd license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses. Suggested citation: Longyear, R. M. Schiller and Music. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1966. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.5149/9781469657820_Longyear Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Longyear, R. M. Title: Schiller and music / by R. M. Longyear. Other titles: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures ; no. 54. Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [1966] Series: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: lccn 66064498 | isbn 978-1-4696-5781-3 (pbk: alk. paper) | isbn 978-1-4696-5782-0 (ebook) Subjects: Schiller, Friedrich, 1759-1805 — Criticism and interpretation. -

MUSIC for a PRUSSIAN KING Friday 23 September 6Pm, Salon Presented by Melbourne Recital Centre and Accademia Arcadia

Accademia Arcadia MUSIC FOR A PRUSSIAN KING Friday 23 September 6pm, Salon Presented by Melbourne Recital Centre and Accademia Arcadia ARTISTS Greg Dikmans, Quantz flute Lucinda Moon, baroque violin Josephine Vains, baroque cello Jacqueline Ogeil, Christofori pianoforte PROGRAM FREDERICK II (THE GREAT) (1712–1786) Sonata in E minor for flute and cembalo Grave – Allegro assai – Presto JOHANN JOACHIM QUANTZ (1697–1773) Sonata in E minor for flute, violin and cembalo, QV 2:21 Adagio – Allegro – Gratioso – Vivace FRANZ BENDA (1709–1786) Sonata per il Violino Solo et Cembalo col Violoncello in G Adagio – Allegretto – Presto CARL PHILIPP EMANUEL BACH (1714–1788) Sonata in A minor for flute, violin and bass, Wq 148 Allegretto – Adagio – Allegro assai ABOUT THE MUSIC No other statesman of his time did so much to promote music at court than Frederick the Great. During his years in Ruppin and Rheinsberg as Crown Prince, Frederick had already assembled a small chamber orchestra. The cultural life at the Prussian court was to receive an entirely new significance after Frederick’s accession to the throne in Berlin in 1740. Within a short time, Berlin’s musical life began to flower thanks to the young king’s decision to construct an opera house and to engage outstanding instrumentalists, singers and conductors. As a compensation for the demanding affairs of state, the Prussian king enjoyed playing and composing for the flute in a style closely following that of histeacher Johann Joachim Quantz. Quantz called this the mixed style, one that combined the German style with the bestelements of the Italian and French national styles. -

The Eminent Pedagogue Johann Joachim Quantz As Instructor Of

Kulturgeschichte Preuûens - Colloquien 6 (2018) Walter Kurt Kreyszig The Eminent Pedagogue Johann Joachim Quantz as Instructor of Frederick the Great During the Years 1728-1741: The Solfeggi, the Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte traversière zu spielen, and the Capricen, Fantasien und Anfangsstücke of Quantz, the Flötenbuch of Frederick the Great and Quantz, and the Achtundzwanzig Variationen über die Arie "Ich schlief, da träumte mir" of Quantz (QV 1:98) Abstract Johann Joachim Quantz (1697-1773), the flute instructor of Frederick the Great (1712-1786), played a seminal role in the development of the Prussian Court Music, during its formative years between 1713 and 1806. As a result of his lifetime appointment to the Court of Potsdam in 1741 by King Frederick the Great, Quantz was involved in numerous facets of the cultural endeavors at the Court, including his contributions to composition, performance and organology. Nowhere was his presence more acutely felt than in his formulation of music-pedagogical materials an activity where his knowledge as a preminent pedagogue and his skills as a composer, organologist and performer fused together in most astounding fashion. Quantz's effectiveness in his teaching of his most eminent student, Frederick the Great, is fully borne out in a number of documents, including the Solfeggi, the Versuch, the Caprices, Fantasien und Anfangsstücke, and the Achtundzwanzig Variationen über die Arie "Ich schlief, da träumte mir". While each document touches on different aspects of the musical discipline, these sources vividly underscore the intersection between musica theorica and musica practica and as such provide testimony of Johann Joachim Quantz as a genuine musicus. -

"Mixed Taste," Cosmopolitanism, and Intertextuality in Georg Philipp

“MIXED TASTE,” COSMOPOLITANISM, AND INTERTEXTUALITY IN GEORG PHILIPP TELEMANN’S OPERA ORPHEUS Robert A. Rue A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2017 Committee: Arne Spohr, Advisor Mary Natvig Gregory Decker © 2017 Robert A. Rue All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Arne Spohr, Advisor Musicologists have been debating the concept of European national music styles in the Baroque period for nearly 300 years. But what precisely constitutes these so-called French, Italian, and German “tastes”? Furthermore, how do contemporary sources confront this issue and how do they delineate these musical constructs? In his Music for a Mixed Taste (2008), Steven Zohn achieves success in identifying musical tastes in some of Georg Phillip Telemann’s instrumental music. However, instrumental music comprises only a portion of Telemann’s musical output. My thesis follows Zohn’s work by identifying these same national styles in opera: namely, Telemann’s Orpheus (Hamburg, 1726), in which the composer sets French, Italian, and German texts to music. I argue that though identifying the interrelation between elements of musical style and the use of specific languages, we will have a better understanding of what Telemann and his contemporaries thought of as national tastes. I will begin my examination by identifying some of the issues surrounding a selection of contemporary treatises, in order explicate the problems and benefits of their use. These sources include Johann Joachim Quantz’s Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte zu spielen (1752), two of Telemann’s autobiographies (1718 and 1740), and Johann Adolf Scheibe’s Critischer Musikus (1737).