The Cinematography of Roger Corman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth. September 2014 Declaration Whilst registered as a candidate for the above degree, I have not been registered for any other research award. The results and conclusions embodied in this thesis are the work of the named candidate and have not been submitted for any other academic award. Word count: 85,810 Abstract Extreme art cinema, has, in recent film scholarship, become an important area of study. Many of the existing practices are motivated by a Franco-centric lens, which ultimately defines transgressive art cinema as a new phenomenon. The thesis argues that a study of extreme art cinema needs to consider filmic production both within and beyond France. It also argues that it requires an historical analysis, and I contest the notion that extreme art cinema is a recent mode of Film production. The study considers extreme art cinema as inhabiting a space between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art forms, noting the slippage between the two often polarised industries. The study has a focus on the paratext, with an analysis of DVD extras including ‘making ofs’ and documentary featurettes, interviews with directors, and cover sleeves. This will be used to examine audience engagement with the artefacts, and the films’ position within the film market. Through a detailed assessment of the visual symbols used throughout the films’ narrative images, the thesis observes the manner in which they engage with the taste structures and pictorial templates of art and exploitation cinema. -

How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime Pdf

FREE HOW I MADE A HUNDRED MOVIES IN HOLLYWOOD AND NEVER LOST A DIME PDF Roger Corman | 254 pages | 01 Sep 1998 | The Perseus Books Group | 9780306808746 | English | Cambridge, MA, United States How I Made A Hundred Movies In Hollywood And Never Lost A Dime by Roger Corman Roger Corman borna filmmaker with several hundred films to his credit, has rightly been called the "King of the B Movies. Since Corman has operated successful independent film production and distribution companies. Roger Corman's childhood gave few clues that, in later years, he would create hundreds of low-budget films that would make him one of Hollywood's best-known directors. He was born in Detroit, Michigan, on April 5,the first child of European immigrants William and Ann Corman; his brother Gene who also became a producer was born 18 months later. As a child Corman was more interested in sports and building model airplanes than in film. William Corman, an engineer, was forced to take a huge pay cut during the Great Depression that began in The family moved to the "poor side" of Beverly Hills, California, while Corman was in high school. He became fascinated with the stories of Edgar Allan Poe asking for a complete set of Poe's works as a giftbut he planned to become an engineer like his father. After graduating from high How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime, Corman studied engineering How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime Stanford University and participated in the Navy's officer training program. -

Why Call Them "Cult Movies"? American Independent Filmmaking and the Counterculture in the 1960S Mark Shiel, University of Leicester, UK

Why Call them "Cult Movies"? American Independent Filmmaking and the Counterculture in the 1960s Mark Shiel, University of Leicester, UK Preface In response to the recent increased prominence of studies of "cult movies" in academic circles, this essay aims to question the critical usefulness of that term, indeed the very notion of "cult" as a way of talking about cultural practice in general. My intention is to inject a note of caution into that current discourse in Film Studies which valorizes and celebrates "cult movies" in particular, and "cult" in general, by arguing that "cult" is a negative symptom of, rather than a positive response to, the social, cultural, and cinematic conditions in which we live today. The essay consists of two parts: firstly, a general critique of recent "cult movies" criticism; and, secondly, a specific critique of the term "cult movies" as it is sometimes applied to 1960s American independent biker movies -- particularly films by Roger Corman such as The Wild Angels (1966) and The Trip (1967), by Richard Rush such as Hell's Angels on Wheels (1967), The Savage Seven, and Psych-Out (both 1968), and, most famously, Easy Rider (1969) directed by Dennis Hopper. Of course, no-one would want to suggest that it is not acceptable to be a "fan" of movies which have attracted the label "cult". But this essay begins from a position which assumes that the business of Film Studies should be to view films of all types as profoundly and positively "political", in the sense in which Fredric Jameson uses that adjective in his argument that all culture and every cultural object is most fruitfully and meaningfully understood as an articulation of the "political unconscious" of the social and historical context in which it originates, an understanding achieved through "the unmasking of cultural artifacts as socially symbolic acts" (Jameson, 1989: 20). -

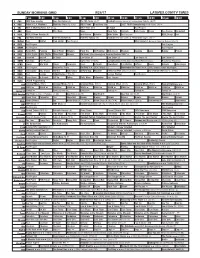

Sunday Morning Grid 9/24/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/24/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Houston Texans at New England Patriots. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Presidents Cup 2017 TOUR Championship Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Rock-Park Outback Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football New York Giants at Philadelphia Eagles. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program MLS Soccer LA Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Cooking Jazzy Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons DW News: Live Coverage of German Election 2017 Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La Comadrita (1978, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana The Reef ›› (2006, Niños) (G) Remember the Titans ››› (2000, Drama) Denzel Washington. -

12 Hours Opens Under Blue Skies and Yellow Flags

C M Y K INSPIRING Instead of loading up on candy, fill your kids’ baskets EASTER with gifts that inspire creativity and learning B1 Devils knock off county EWS UN s rivals back to back A9 NHighlands County’s Hometown Newspaper-S Since 1927 75¢ Cammie Lester to headline benefit Plan for spray field for Champion for Children A5 at AP airport raises a bit of a stink A3 www.newssun.com Sunday, March 16, 2014 Health A PERFECT DAY Dept. in LP to FOR A RACE be open To offer services every other Friday starting March 28 BY PHIL ATTINGER Staff Writer SEBRING — After meet- ing with school and coun- ty elected officials Thurs- day, Florida Department of Health staff said the Lake Placid office at 106 N, Main Ave. will be reopen- ing, but with a reduced schedule. Tom Moran, depart- ment spokesman, said in a Katara Simmons/News-Sun press release that the Flor- The Mobil 1 62nd Annual 12 Hours of Sebring gets off to a flawless start Saturday morning at Sebring International Raceway. ida Department of Health in Highlands County is continuing services at the Lake Placid office ev- 12 Hours opens under blue ery other Friday starting March 28. “The Department con- skies and yellow flags tinues to work closely with local partners to ensure BY BARRY FOSTER Final results online at Gurney Bend area of the health services are avail- News-Sun Correspondent www.newssun.com 3.74-mile course. Emergen- able to the people of High- cy workers had a tough time lands County. -

Vision, Desire and Economies of Transgression in the Films of Jess Franco

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 1 Journeys into Perversion: Vision, Desire and Economies of Transgression in the Films of Jess Franco Glenn Ward Doctor of Philosophy University of Sussex May 2011 2 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been, and will not be, submitted whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature:……………………………………… 3 Summary Due to their characteristic themes (such as „perverse‟ desire and monstrosity) and form (incoherence and excess), exploitation films are often celebrated as inherently subversive or transgressive. I critically assess such claims through a close reading of the films of the Spanish „sex and horror‟ specialist Jess Franco. My textual and contextual analysis shows that Franco‟s films are shaped by inter-relationships between authorship, international genre codes and the economic and ideological conditions of exploitation cinema. Within these conditions, Franco‟s treatment of „aberrant‟ and gothic desiring subjectivities appears contradictory. Contestation and critique can, for example, be found in Franco‟s portrayal of emasculated male characters, and his female vampires may offer opportunities for resistant appropriation. -

Contenido Estrenos Mexicanos

Contenido estrenos mexicanos ............................................................................120 programas especiales mexicanos .................................. 122 Foro de los Pueblos Indígenas 2019 .......................................... 122 Programa Exilio Español ....................................................................... 123 introducción ...........................................................................................................4 Programa Luis Buñuel ............................................................................. 128 Presentación ............................................................................................................... 5 El Día Después ................................................................................................ 132 ¡Bienvenidos a Morelia! ................................................................................... 7 Feratum Film Festival .............................................................................. 134 Mensaje de la Secretaría de Cultura ....................................................8 ......... 10 Mensaje del Instituto Mexicano de Cinematografía funciones especiales mexicanas .......................................137 17° Festival Internacional de Cine de Morelia ............................11 programas especiales internacionales................148 ...........................................................................................................................12 jurados Programa Agnès Varda ...........................................................................148 -

Nosferatu. Revista De Cine (Donostia Kultura)

Nosferatu. Revista de cine (Donostia Kultura) Título: No diga bajo presupuesto, diga ... Roger Connan Autor/es: Valencia, Manuel Citar como: Valencia, M. (1994). No diga bajo presupuesto, diga ... Roger Connan. Nosferatu. Revista de cine. (14):79-89. Documento descargado de: http://hdl.handle.net/10251/40892 Copyright: Reserva de todos los derechos (NO CC) La digitalización de este artículo se enmarca dentro del proyecto "Estudio y análisis para el desarrollo de una red de conocimiento sobre estudios fílmicos a través de plataformas web 2.0", financiado por el Plan Nacional de I+D+i del Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad del Gobierno de España (código HAR2010-18648), con el apoyo de Biblioteca y Documentación Científica y del Área de Sistemas de Información y Comunicaciones (ASIC) del Vicerrectorado de las Tecnologías de la Información y de las Comunicaciones de la Universitat Politècnica de València. Entidades colaboradoras: Roger Corman :rj c--~- ~ c• 4 e :) ·~ No diga bajo presupuesto, diga ... Roger Corman Manuel Valencia í, bajo presupuesto, por céntimo, Ed. Laertes, Barcelona, los niveles de audiencia empeza que como bien explica el 1992), jamás realizó una pelícu ron a bajar, los estudios estimu Spropio Corman en su es la de serie B: "La serie B databa laban al público a ir al cine con pléndida y socarrona autobio de la Depresión, sólo fue un su el incentivo de los programas grafía (Cómo hice cien films en i·eso hasta principios de los años dobles, donde podían verse dos Hollywood y nunca perdí ni un cincuenta. En los treinta, cuando películas al precio de una. -

The Dark Past Keeps Returning: Gender Themes in Neo-Noir by Heather Fireman

The Dark Past Keeps Returning: Gender Themes in Neo-Noir by Heather Fireman "Films are full of good things which really ought to be invented all over again. Again and again. Invented - not repeated. The good things should be found - found - in that precious spirit of the first time out, and images discovered - not referred to.... Sure, everything's been done.... Hell, everything had all been done when I started" -Orson Welles (Naremore 219). Film noir, an enigmatic and compelling mode, can and has been resurrected in many movies in recent years. So-called "neo-noirs" evoke the look, style, mood, or even just the feel of classic noir. Having sprung from a particular moment in history and resonating with the mentality of its audiences, noir should also be considered in terms of a context, which was vital to its ability to create meaning for its original audiences. We can never know exactly how those audiences viewed the noirs of the 1940s and 50s, but modern audiences obviously view them differently, in contexts "far removed from the ones for which they were originally intended" (Naremore 261). These films externalized fears and anxieties of American society of the time, generating a dark feeling or mood to accompany its visual style. But is a noir "feeling" historically bound? What does this mean for neo-noirs? Contemporary America has distinctive features that set it apart from the past. Even though neo-noir films may borrow generic conventions of classic noir, the "language" of noir is used to express anxieties belonging to modern times. -

The End of Japanese Cinema

THE END OF JAPANESE CINEMA TIMES ALEXANDER ZAHLTEN THE END OF JAPA NESE CINEMA studies of the weatherhead east asian institute, columbia university. The Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute of Columbia University w ere inaugurated in 1962 to bring to a wider public the results of significant new research on modern and con temporary East Asia. alexander zahlten THE END OF JAPA NESE CINEMA Industrial Genres, National Times, and Media Ecologies Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2017 © 2017 DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Text designed by Courtney Leigh Baker Typeset in Arno Pro and Din by Westchester Publishing Ser vices Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Zahlten, Alexander, [date] author. Title: The end of Japa nese cinema : industrial genres, national times, and media ecologies / Alexander Zahlten. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Series: Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version rec ord and cip data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers: lccn 2017012588 (print) lccn 2017015688 (ebook) isbn 9780822372462 (ebook) isbn 9780822369295 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822369448 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Motion pictures— Japan— History—20th century. | Mass media— Japan— History—20th century. Classification: lcc pn1993.5.j3 (ebook) | lcc pn1993.5.j3 Z34 2017 (print) -

JACK ARNOLD Di Renato Venturelli

JACK ARNOLD di Renato Venturelli Tra gli autori della fantascienza anni ‘50, che rinnovò la tradizione del cinema fantastico e dell’horror, il nome che si impone con più evidenza è quello di Jack Amold. Il motivo di questo rilievo non sta tanto nell’ aver diretto i capolavori assoluti del decennio (La cosa è di Hawks, L’invasione degli ultracorpi è di Siegel...), quanto nell’aver realizzato un corpus di film compatto per stile e notevole nel suo insieme per quantità e qualità. Gli otto film fantastici realizzati fra il 1953 e il 1959 testimoniano cioè un autore riconoscibile, oltre a scandire tappe fondamentali per la mitologia del cinema fantastico, dalla Creatura della Laguna Nera (unico esempio degli anni ‘50 ad essere entrato nel pantheon dei mostri classici) alla gigantesca tarantola, dalla metafora esistenziale di Radiazioni B/X agli scenari desertici in cui l’uomo si trova improvvisamente di fronte ai limiti delle proprie conoscenze razionali. Uno dei motivi di compattezza del lavoro di Amold sta nella notevole autonomia con cui poté lavorare. Il suo primo film di fantascienza, Destinazione… Terra (1953), segnava infatti il primo tentativo in questa direzione (e nelle tre dimensioni) da parte della Universal-International. Il successo che ottenne, e che assieme agli incassi del Mostro della laguna nera risollevò la compagnia da una difficile situazione economica, fu tale da permettere ad Arnold di ritagliarsi una zona di relativa autonomia all’interno dello studio: “Nessuno a quell’epoca era un esperto nel fare film di fantascienza, così io pretesi di esserlo. Non lo ero, naturalmente, ma lo studio non lo sapeva, e così non si misero mai a discutere, qualsiasi cosa facessi”. -

American International Pictures (AIP) Est Une Société De Production Et

American International Pictures (AIP) est une société de production et distribution américaine, fondée en 1956 depuis "American Releasing Corporation" (en 1955) par James H. Nicholson et Samuel Z. Arkoff, dédiée à la production de films indépendants à petits budgets, principalement à destination des adolescents des années 50, 60 et 70. 1 Né à Fort Dodge, Iowa à une famille juive russe, Arkoff a d'abord étudié pour être avocat. Il va s’associer avec James H. Nicholson et le producteur-réalisateur Roger Corman, avec lesquels il produira dix-huit films. Dans les années 1950, lui et Nicholson fondent l'American Releasing Corporation, qui deviendra plus tard plus connue sous le nom American International Pictures et qui produira plus de 125 films avant la disparition de l'entreprise dans les années 1980. Ces films étaient pour la plupart à faible budget, avec une production achevée en quelques jours. Arkoff est également crédité du début de genres cinématographiques, comme le Parti Beach et les films de motards, enfin sa société jouera un rôle important pour amener le film d'horreur à un niveau important avec Blacula, I Was a Teenage Werewolf et Le Chose à deux têtes. American International Pictures films engage très souvent de grands acteurs dans les rôles principaux, tels que Boris Karloff, Elsa Lanchester et Vincent Price, ainsi que des étoiles montantes qui, plus tard deviendront très connus comme Don Johnson, Nick Nolte, Diane Ladd, et Jack Nicholson. Un certain nombre d'acteurs rejetées ou 2 négligées par Hollywood dans les années 1960 et 1970, comme Bruce Dern et Dennis Hopper, trouvent du travail dans une ou plusieurs productions d’Arkoff.