The End of Japanese Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film Funding Grants Programme 2013

Film Funding Grants Programme 2013 Film Funding Grants Programme 2013 Doha Film Institute established its Grants We contribute to films that have strong directorial Programme with the vision of fostering creative vision and that are challenging, creative and talent in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) thought-provoking. Support for grantees is holistic, region. We are proud that over its first three- with financial assistance bolstered by professional and-a-half years the programme supported the development, mentorship and creative development development of more than 137 projects from opportunities that are made available throughout 14 countries. a project’s life cycle. In 2013, the Institute embarked on a new phase of the Grants Programme designed to further the It is our hope that through the Grants Programme goal of nurturing emerging talent. Projects from and the growing number of its alumni, we will all over the world became eligible for funding, continue to widen our flourishing community with a special focus on first- and second-time of filmmakers. As we extend our reach, we also filmmakers. enable professional, cultural and creative exchanges between our local talent and the wider international Alongside this expansion, the Institute’s industry. commitment to talent from the MENA region remains strong, with specific categories and I am honoured to welcome our newest grant criteria in place. Our focus on first- and second- recipients to the Doha Film Institute family. time filmmakers will greatly enhance our ability to discover and nurture new voices, both at home in Abdulaziz Al-Khater Qatar and around the globe. -

Brittisk Noir Mörker, Våld Och Sjabbig Glamour

november–januari 1 Stockholm Brittisk noir Mörker, våld och sjabbig glamour November 2019–januari 2020: Trinh T. Minh-ha, Kinuyo Tanaka, Nils Poppe, Alfred Hitchcock, David Cronenberg 2 Innehåll november–januari Inledning ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 4 Alfred Hitchcock .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 The Master of Suspense. Trinh T. Minh-ha .................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Etnografisk film, essäer och lekfull fiktion. David Cronenberg ............................................................................................................................................................ 8 Body horror och ”tankeväckande skräp”. Kinuyo Tanaka ................................................................................................................................................................... 11 Berömd japansk skådespelare och regipionjär. 6 Walter Hill ................................................................................................................................................................................. 14 Kultförklarade filmer om sammanbitna män. Ermanno Olmi ................................................................................................................................................................... -

Jewish Identity and German Landscapes in Konrad Wolf's I Was Nineteen

Religions 2012, 3, 130–150; doi:10.3390/rel3010130 OPEN ACCESS religions ISSN 2077-1444 www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Article Homecoming as a National Founding Myth: Jewish Identity and German Landscapes in Konrad Wolf’s I was Nineteen Ofer Ashkenazi History Department, University of Minnesota, 1110 Heller Hall, 271 19th Ave S, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: 1-651-442-3030 Received: 5 January 2012; in revised form: 13 March 2012 / Accepted: 14 March 2012 / Published: 22 March 2012 Abstract: Konrad Wolf was one of the most enigmatic intellectuals of East Germany. The son of the Jewish Communist playwright Friedrich Wolf and the brother of Markus Wolf— the head of the GDR‘s Foreign Intelligence Agency—Konrad Wolf was exiled in Moscow during the Nazi era and returned to Germany as a Red Army soldier by the end of World War Two. This article examines Wolf‘s 1968 autobiographical film I was Nineteen (Ich war Neunzehn), which narrates the final days of World War II—and the initial formation of postwar reality—from the point of view of an exiled German volunteer in the Soviet Army. In analyzing Wolf‘s portrayals of the German landscape, I argue that he used the audio- visual clichés of Heimat-symbolism in order to undermine the sense of a homogenous and apolitical community commonly associated with this concept. Thrown out of their original contexts, his displaced Heimat images negotiate a sense of a heterogeneous community, which assumes multi-layered identities and highlights the shared ideology rather than the shared origins of the members of the national community. -

1 OR 2 THINGS I DON't KNOW ABOUT HIM Playing with DUMMY P37 UK Super16mm 11 Mins Director/Screenplay Maurizio Von Trapp Produc

1 OR 2 THINGS I DON’T KNOW ABOUT HIM THE AMBIENT MEDIUM THE BENT PENNY Playing with DUMMY p37 Playing with BLACKSPOT p64 Playing with SENSELESS p39 UK Super16mm 11 mins Director/Screenplay Maurizio Von USA MiniDV 10 mins Director/Producer/Screenplay/DoP UK HDCam 16 mins Director/Screenplay Darrel J Butlin Trapp Producer/DoP Carolina Costa Cast Pedro Reichert, Bill Domonkos Print Source [email protected] Producer Jeremy Vivian DoP Louie Blystad-Collins Cast James Nield Print Source [email protected] Inspired by nineteenth century spirit photography, science fic- Angus Barr, Guy Davies, Kay Curram, Olegar Fedoro Print What is one to do when left alone? Arising questions and sad- tion and paranormal phenomena, The Ambient Medium is the Source [email protected] ness. This is where Guido finds himself and he needs to talk. material surrounding or contacting an organism, through which Three stories are linked by a penny that travels from person to chemicals, energy or pollutants can reach the organism. person. DIRECTIONS DJ:LA EMMA’S LAST DATE Playing with WHO IS KK DOWNEY? p68 Playing with ANÕ UNÃ p56 Playing with ONE DAY REMOVALS p39 Australia Super35 15 mins Director/Screenplay Kasimir USA 4 mins Dir/S’play Jerry Chan Producer/DoP Mitchel UK HD 11 mins Director Chris Thomas Producer Leanne Savill Burgess Producer Chris Kamen DoP Adam Arkapaw Cast Dumlao Print Source [email protected] Screenplay Hugo Simms DoP Chris Bairstow Print Source Greg Muller Print Source [email protected] Remixes the frenzied sights and sounds of the Los Angeles [email protected] A desperate man finds inspiration in a broken shopping trolley. -

East-West Film Journal, Volume 3, No. 2

EAST-WEST FILM JOURNAL VOLUME 3 . NUMBER 2 Kurosawa's Ran: Reception and Interpretation I ANN THOMPSON Kagemusha and the Chushingura Motif JOSEPH S. CHANG Inspiring Images: The Influence of the Japanese Cinema on the Writings of Kazuo Ishiguro 39 GREGORY MASON Video Mom: Reflections on a Cultural Obsession 53 MARGARET MORSE Questions of Female Subjectivity, Patriarchy, and Family: Perceptions of Three Indian Women Film Directors 74 WIMAL DISSANAYAKE One Single Blend: A Conversation with Satyajit Ray SURANJAN GANGULY Hollywood and the Rise of Suburbia WILLIAM ROTHMAN JUNE 1989 The East- West Center is a public, nonprofit educational institution with an international board of governors. Some 2,000 research fellows, grad uate students, and professionals in business and government each year work with the Center's international staff in cooperative study, training, and research. They examine major issues related to population, resources and development, the environment, culture, and communication in Asia, the Pacific, and the United States. The Center was established in 1960 by the United States Congress, which provides principal funding. Support also comes from more than twenty Asian and Pacific governments, as well as private agencies and corporations. Kurosawa's Ran: Reception and Interpretation ANN THOMPSON AKIRA KUROSAWA'S Ran (literally, war, riot, or chaos) was chosen as the first film to be shown at the First Tokyo International Film Festival in June 1985, and it opened commercially in Japan to record-breaking busi ness the next day. The director did not attend the festivities associated with the premiere, however, and the reception given to the film by Japa nese critics and reporters, though positive, was described by a French critic who had been deeply involved in the project as having "something of the air of an official embalming" (Raison 1985, 9). -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

Filmography of Case Study Films (In Chronological Order of Release)

FILMOGRAPHY OF CASE STUDY FILMS (IN CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER OF RELEASE) Kairo / Pulse 118 mins, col. Released: 2001 (Japan) Director: Kiyoshi Kurosawa Screenplay: Kiyoshi Kurosawa Cinematography: Junichiro Hayashi Editing: Junichi Kikuchi Sound: Makio Ika Original Music: Takefumi Haketa Producers: Ken Inoue, Seiji Okuda, Shun Shimizu, Atsuyuki Shimoda, Yasuyoshi Tokuma, and Hiroshi Yamamoto Main Cast: Haruhiko Kato, Kumiko Aso, Koyuki, Kurume Arisaka, Kenji Mizuhashi, and Masatoshi Matsuyo Production Companies: Daiei Eiga, Hakuhodo, Imagica, and Nippon Television Network Corporation (NTV) Doruzu / Dolls 114 mins, col. Released: 2002 (Japan) Director: Takeshi Kitano Screenplay: Takeshi Kitano Cinematography: Katsumi Yanagijima © The Author(s) 2016 217 A. Dorman, Paradoxical Japaneseness, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-55160-3 218 FILMOGRAPHY OF CASE STUDY FILMS… Editing: Takeshi Kitano Sound: Senji Horiuchi Original Music: Joe Hisaishi Producers: Masayuki Mori and Takio Yoshida Main Cast: Hidetoshi Nishijima, Miho Kanno, Tatsuya Mihashi, Chieko Matsubara, Tsutomu Takeshige, and Kyoko Fukuda Production Companies: Bandai Visual Company, Offi ce Kitano, Tokyo FM Broadcasting Company, and TV Tokyo Sukiyaki uesutan jango / Sukiyaki Western Django 121 mins, col. Released: 2007 (Japan) Director: Takashi Miike Screenplay: Takashi Miike and Masa Nakamura Cinematography: Toyomichi Kurita Editing: Yasushi Shimamura Sound: Jun Nakamura Original Music: Koji Endo Producers: Nobuyuki Tohya, Masao Owaki, and Toshiaki Nakazawa Main Cast: Hideaki Ito, Yusuke Iseya, Koichi Sato, Kaori Momoi, Teruyuki Kagawa, Yoshino Kimura, Masanobu Ando, Shun Oguri, and Quentin Tarantino Production Companies: A-Team, Dentsu, Geneon Entertainment, Nagoya Broadcasting Network (NBN), Sedic International, Shogakukan, Sony Pictures Entertainment (Japan), Sukiyaki Western Django Film Partners, Toei Company, Tokyu Recreation, and TV Asahi Okuribito / Departures 130 mins, col. -

Exploring Films About Ethical Leadership: Can Lessons Be Learned?

EXPLORING FILMS ABOUT ETHICAL LEADERSHIP: CAN LESSONS BE LEARNED? By Richard J. Stillman II University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center Public Administration and Management Volume Eleven, Number 3, pp. 103-305 2006 104 DEDICATED TO THOSE ETHICAL LEADERS WHO LOST THEIR LIVES IN THE 9/11 TERROIST ATTACKS — MAY THEIR HEORISM BE REMEMBERED 105 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 106 Advancing Our Understanding of Ethical Leadership through Films 108 Notes on Selecting Films about Ethical Leadership 142 Index by Subject 301 106 PREFACE In his preface to James M cG regor B urns‘ Pulitzer–prizewinning book, Leadership (1978), the author w rote that ―… an im m ense reservoir of data and analysis and theories have developed,‖ but ―w e have no school of leadership.‖ R ather, ―… scholars have worked in separate disciplines and sub-disciplines in pursuit of different and often related questions and problem s.‖ (p.3) B urns argued that the tim e w as ripe to draw together this vast accumulation of research and analysis from humanities and social sciences in order to arrive at a conceptual synthesis, even an intellectual breakthrough for understanding of this critically important subject. Of course, that was the aim of his magisterial scholarly work, and while unquestionably impressive, his tome turned out to be by no means the last word on the topic. Indeed over the intervening quarter century, quite to the contrary, we witnessed a continuously increasing outpouring of specialized political science, historical, philosophical, psychological, and other disciplinary studies with clearly ―no school of leadership‖with a single unifying theory emerging. -

The Picture of Abjection: Film, Fetish, and the Nature of Difference

The Picture of Abjection: Film, Fetish, and the Nature of Difference By Tina Chanter Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008. ISBN: 9780253219183. 15 illustrations, 377 pp. £19.99 (pbk) A review by Adrienne Angelo, Angelo, University of West Georgia, USA How do scholars and others with an interest in film studies and psychoanalysis engage with existing theoretical discourses on race, gender, culture and sexual difference in order to bypass the often polemicized and contested paradigm of fetishism and voyeurism, two critical modes that have dominated and continue to dominate film theory? It is this problematic that Tina Chanter explores in The Picture of Abjection: Film, Fetish and the Nature of Difference. For Chanter, drawing largely upon Kristeva's theoretical considerations of abjection, a point of entry to this endeavor lies precisely in further developing the implications of abjection as a "staging of a defensive dynamic that has the potential to significantly rework the imaginary commitments of Oedipal theory, specifically its privileging of masculinity and femininity" (17). Chanter's primary goal appears to be to develop a new critical model at the very center of which lies that which is otherwise neglected, excluded and expelled from dominant cultural discourse for being "too much", too "other". However, for as much as Chanter promotes a consideration of film and film theory, there is less an in-depth reading of films per se than a highly informed reconsideration of theoretical notions of subjectivity and the subject, one read through the lens of abjection and its destabilizing and thus subversive potential for considering marginalized identities and their representation in film theory. -

The Dark Past Keeps Returning: Gender Themes in Neo-Noir by Heather Fireman

The Dark Past Keeps Returning: Gender Themes in Neo-Noir by Heather Fireman "Films are full of good things which really ought to be invented all over again. Again and again. Invented - not repeated. The good things should be found - found - in that precious spirit of the first time out, and images discovered - not referred to.... Sure, everything's been done.... Hell, everything had all been done when I started" -Orson Welles (Naremore 219). Film noir, an enigmatic and compelling mode, can and has been resurrected in many movies in recent years. So-called "neo-noirs" evoke the look, style, mood, or even just the feel of classic noir. Having sprung from a particular moment in history and resonating with the mentality of its audiences, noir should also be considered in terms of a context, which was vital to its ability to create meaning for its original audiences. We can never know exactly how those audiences viewed the noirs of the 1940s and 50s, but modern audiences obviously view them differently, in contexts "far removed from the ones for which they were originally intended" (Naremore 261). These films externalized fears and anxieties of American society of the time, generating a dark feeling or mood to accompany its visual style. But is a noir "feeling" historically bound? What does this mean for neo-noirs? Contemporary America has distinctive features that set it apart from the past. Even though neo-noir films may borrow generic conventions of classic noir, the "language" of noir is used to express anxieties belonging to modern times. -

Programmation Septembre 2020

Une sélection du meilleur du cinéma de patrimoine par Carlotta Films ! PROGRAMMATION SEPTEMBRE 2020 MIKIO NARUSE RÉALISATEUR DU MOIS 4 fi lms majeurs AU GRÉ DU COURANT (1956) QUAND UNE FEMME MONTE L’ESCALIER (1960) UNE FEMME DANS LA TOURMENTE (1964) NUAGES ÉPARS (1967) UNE FAMILLE DÉVOYÉE ÉVÉNEMENT SPÉCIAL : AVANT-PREMIÈRE EXCEPTIONNELLE un fi lm de Masayuki Suo (1984) - EXCLUSIVITÉ LE VIDÉO CLUB CARLOTTA FILMS (Int. -16 ans) - THE ENDLESS SUMMER DÉJÀ CULTE un fi lm de Bruce Brown (1966) THE EXTERMINATOR (LE DROIT DE TUER) DÉJÀ CULTE un fi lm de James Glickenhaus (1980) A FULLER LIFE DÉCOUVERTES & RARETÉS un fi lm de Samantha Fuller (2013) LE COUSIN JULES DÉCOUVERTES & RARETÉS un fi lm de Dominique Benicheti (1973) LE MONDE SUR LE FIL LE FILM FLEUVE un fi lm de Rainer Werner Fassbinder (1973) LEVIDEOCLUB.CARLOTTAFILMS.COM CARLOTTA FILMS 5-7, imp. Carrière-Mainguet 75011 Paris Tél. : 01 42 24 10 86 LE RÉALISATEUR DU MOIS MIKIO NARUSE DÉCOUVREZ 4 MAGNIFIQUES PORTRAITS DE FEMME PAR L’UN DES PLUS GRANDS CINÉASTES JAPONAIS AU GRÉ DU COURANT QUAND UNE FEMME MONTE L’ESCALIER UNE FEMME DANS LA TOURMENTE NUAGES ÉPARS Longtemps méconnue en Occident, l’œuvre de Mikio Naruse est aujourd’hui élevée au même rang que celle de ses compatriotes Mizoguchi, Ozu et Kurosawa. À partir des années 1950, il se spécialise dans le shomin geki, genre qui vise à dépeindre le quotidien des gens de la classe moyenne. Son œuvre à la fois poétique et réaliste, pleinement ancrée dans son temps, donne à voir de magnifiques portraits de femmes, portés par les plus grandes actrices du cinéma nippon comme Hideko Takamine, sa muse, ou Yoko Tsukasa. -

Class Schedule Listing Mar 28, 2018

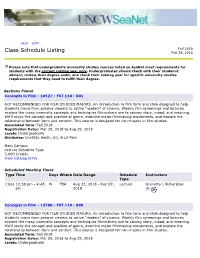

HELP | EXIT Fall 2018 Class Schedule Listing Mar 28, 2018 Please note that undergraduate university studies courses listed on SeaNet meet requirements for students with the current catalog year only. Undergraduates should check with their academic advisor, review their degree audit, and check their catalog year for specific university studies requirements that they need to fulfill their degree. Sections Found Concepts in Film - 10527 - FST 110 - 001 NOT RECOMMENDED FOR FILM STUDIES MAJORS. An introduction to film form and style designed to help students move from passive viewers to active “readers” of cinema. Weekly film screenings and lectures explore the many cinematic concepts and techniques filmmakers use to convey story, mood, and meaning. We’ll study the concept and practice of genre, examine major filmmaking movements, and explore the relationship between form and content. This course is designed for non-majors in film studies. Associated Term: Fall 2018 Registration Dates: Mar 29, 2018 to Aug 29, 2018 Levels: Undergraduate Attributes: UnvStdy Aesth, Int, & Lit Pers Main Campus Lecture Schedule Type 3.000 Credits View Catalog Entry Scheduled Meeting Times Type Time Days Where Date Range Schedule Instructors Type Class 12:30 pm - 4:45 W TBA Aug 22, 2018 - Dec 07, Lecture Granetta L Richardson pm 2018 (P) Concepts in Film - 12780 - FST 110 - 800 NOT RECOMMENDED FOR FILM STUDIES MAJORS. An introduction to film form and style designed to help students move from passive viewers to active “readers” of cinema. Weekly film screenings and lectures explore the many cinematic concepts and techniques filmmakers use to convey story, mood, and meaning.