Copyright by John Samuel Wagle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cessna 172 in Flight 1964 Cessna 172E 1965 Cessna F172G

Cessna 172 in flight 1964 Cessna 172E 1965 Cessna F172G 1971 Cessna 172 The 1957 model Cessna 172 Skyhawk had no rear window and featured a "square" fin design Airplane Cessna 172 single engine aircraft, flies overhead after becoming airborne. Catalina Island airport, California (KAVX) 1964 Cessna 172E (G- ASSS) at Kemble airfield, Gloucestershire, England. The Cessna 172 Skyhawk is a four-seat, single-engine, high-wing airplane. Probably the most popular flight training aircraft in the world, the first production models were delivered in 1957, and it is still in production in 2005; more than 35,000 have been built. The Skyhawk's main competitors have been the popular Piper Cherokee, the rarer Beechcraft Musketeer (no longer in production), and, more recently, the Cirrus SR22. The Skyhawk is ubiquitous throughout the Americas, Europe and parts of Asia; it is the aircraft most people visualize when they hear the words "small plane." More people probably know the name Piper Cub, but the Skyhawk's shape is far more familiar. The 172 was a direct descendant of the Cessna 170, which used conventional (taildragger) landing gear instead of tricycle gear. Early 172s looked almost identical to the 170, with the same straight aft fuselage and tall gear legs, but later versions incorporated revised landing gear, a lowered rear deck, and an aft window. Cessna advertised this added rear visibility as "Omnivision". The final structural development, in the mid-1960s, was the sweptback tail still used today. The airframe has remained almost unchanged since then, with updates to avionics and engines including (most recently) the Garmin G1000 glass cockpit. -

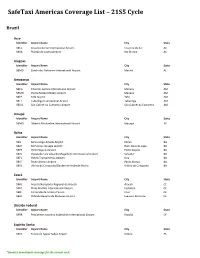

Safetaxi Americas Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Americas Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Brazil Acre Identifier Airport Name City State SBCZ Cruzeiro do Sul International Airport Cruzeiro do Sul AC SBRB Plácido de Castro Airport Rio Branco AC Alagoas Identifier Airport Name City State SBMO Zumbi dos Palmares International Airport Maceió AL Amazonas Identifier Airport Name City State SBEG Eduardo Gomes International Airport Manaus AM SBMN Ponta Pelada Military Airport Manaus AM SBTF Tefé Airport Tefé AM SBTT Tabatinga International Airport Tabatinga AM SBUA São Gabriel da Cachoeira Airport São Gabriel da Cachoeira AM Amapá Identifier Airport Name City State SBMQ Alberto Alcolumbre International Airport Macapá AP Bahia Identifier Airport Name City State SBIL Bahia-Jorge Amado Airport Ilhéus BA SBLP Bom Jesus da Lapa Airport Bom Jesus da Lapa BA SBPS Porto Seguro Airport Porto Seguro BA SBSV Deputado Luís Eduardo Magalhães International Airport Salvador BA SBTC Hotéis Transamérica Airport Una BA SBUF Paulo Afonso Airport Paulo Afonso BA SBVC Vitória da Conquista/Glauber de Andrade Rocha Vitória da Conquista BA Ceará Identifier Airport Name City State SBAC Aracati/Aeroporto Regional de Aracati Aracati CE SBFZ Pinto Martins International Airport Fortaleza CE SBJE Comandante Ariston Pessoa Cruz CE SBJU Orlando Bezerra de Menezes Airport Juazeiro do Norte CE Distrito Federal Identifier Airport Name City State SBBR Presidente Juscelino Kubitschek International Airport Brasília DF Espírito Santo Identifier Airport Name City State SBVT Eurico de Aguiar Salles Airport Vitória ES *Denotes -

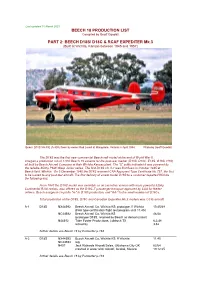

BEECH D18S/ D18C & RCAF EXPEDITER Mk.3 (Built at Wichita, Kansas Between 1945 and 1957)

Last updated 10 March 2021 BEECH 18 PRODUCTION LIST Compiled by Geoff Goodall PART 2: BEECH D18S/ D18C & RCAF EXPEDITER Mk.3 (Built at Wichita, Kansas between 1945 and 1957) Beech D18S VH-FIE (A-808) flown by owner Rod Lovell at Mangalore, Victoria in April 1984. Photo by Geoff Goodall The D18S was the first new commercial Beechcraft model at the end of World War II. It began a production run of 1,800 Beech 18 variants for the post-war market (D18S, D18C, E18S, G18S, H18), all built by Beech Aircraft Company at their Wichita Kansas plant. The “S” suffix indicated it was powered by the reliable 450hp P&W Wasp Junior series. The first D18S c/n A-1 was first flown in October 1945 at Beech field, Wichita. On 5 December 1945 the D18S received CAA Approved Type Certificate No.757, the first to be issued to any post-war aircraft. The first delivery of a new model D18S to a customer departed Wichita the following day. From 1947 the D18C model was available as an executive version with more powerful 525hp Continental R-9A radials, also offered as the D18C-T passenger transport approved by CAA for feeder airlines. Beech assigned c/n prefix "A-" to D18S production, and "AA-" to the small number of D18Cs. Total production of the D18S, D18C and Canadian Expediter Mk.3 models was 1,035 aircraft. A-1 D18S NX44592 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS: prototype, ff Wichita 10.45/48 (FAA type certification flight test program until 11.45) NC44592 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS 46/48 (prototype D18S, retained by Beech as demonstrator) N44592 Tobe Foster Productions, Lubbock TX 6.2.48 retired by 3.52 further details see Beech 18 by Parmerter p.184 A-2 D18S NX44593 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS: ff Wichita 11.45 NC44593 reg. -

Va-Vol-44-No-6-Nov-Dec-2016

NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2016 Cruising the Vintage Line Vintage Airplane Straight & Level STAFF GEOFF ROBISON EAA Publisher/Chairman of the Board VAA PRESIDENT, EAA Lifetime 268346, VAA Lifetime 12606 . Jack J. Pelton Editor ............... Jim Busha . [email protected] VAA Executive Administrator . Hannah Hupfer 2016 — Certainly, a year to remember! 920-426-6110 .......... [email protected] Art Director ............ Olivia Phillip Trabbold Happy Thanksgiving and Merry Christmas to all of our members! Graphic Designer .......Amanda Million I believe 2016 was certainly an exceptional year for the membership of the VAA. But for me personally, I felt it was just a great year for some of the ADVERTISING: Vice President of Business Development best accomplishments we as an organization have executed on in recent Dave Chaimson ......... [email protected] times. I am always amazed every year to see how generous the VAA mem- Advertising Manager bership is to this organization. We actually received significant financial Sue Anderson .......... [email protected] support from a very broad base of our membership. Whether it’s you sup- porting the Friends of the Red Barn fund, or donating dollars designated VAA, PO Box 3086, Oshkosh, WI 54903 toward supporting the new construction at the Vintage Tall Pines Cafe, or Website: www.vintageaircraft.org Email: [email protected] incoming funds directed toward the funding of the numerous individual programs we offer each year during AirVenture, they all add up to being VISIT very significant in our endeavors to constantly improve the offerings we www.vintageaircraft.org provide the membership at Oshkosh each year. for the latest in information and news AirVenture Oshkosh 2016 was an absolute success story when you take and for the electronic newsletter: a true measurement of the number and quality of the features and attrac- Vintage AirMail tions on the field this year. -

Cessna Aircraft Company-A Short History

Cessna Aircraft Company Info from (address no longer valid) http://www.wingsoverkansas.com/history/article.asp?id=627 Clyde Vernon Cessna, whose 250-year American lineage stemmed from French and German ancestry, was born in Hawthorne, Iowa, December 5, 1879. At the age of two, he traveled the long overland journey with his parents to Kingman County, Kansas, where they settled on a homestead along the Chickasaw River. In early boyhood his aptitudes revealed visionary creativity and mechanical talents that found instant outlets in the dire necessities and rugged demands of pioneer life. In this environment he became a self taught expert in developing and improving farm machinery and farming methods for producing food and for services that were non-existent. As the family increased to nine, the challenges and opportunities presented themselves in an extended world of the early automobile. Becoming the owner of a first horseless carriage, he followed avidly the trends in improvement and in this way became a mechanic salesman and in time operated an automobile sales agency in Enid, Oklahoma. He became captivated with flying after learning of Louis Blériot's 1909 flight across the English Channel. Traveling east to New York, Cessna spent a month at the Queen Airplane Company factory, learning the fundamentals of flight and the art of plane building. He became so enthusiastic about flying that he spent his life savings of $7,500 to buy an exact copy of the Blériot XI monoplane, shipping it west to his home in Enid, Oklahoma. Cessna flew this aircraft, along with others he designed and built, in exhibition flights throughout the Midwest, continuously modifying the planes to improve their performance. -

“Working with Fire” (Mort’S Aviation Experiences & History)

“Working With Fire” (Mort’s Aviation Experiences & History) Mort Brown Photo by Don Wiley By Mort & Sharon Brown Copyrighted 2007 (All Rights Reserved) TO: All Aviation Enthusiasts FROM: Mort & Sharon Brown RE: “Working With Fire” (Mort’s Aviation Experiences) Dear Aviation Enthusiast: Mort is the (first) retired Chief Pilot of Production Flight Test, Cessna Aircraft Company, from 1937 - 1972. “Working With Fire” contains selected aviation experiences from Mort’s biography. The text in Mort’s first presentation and CD, “Pistons, Props, and Tail Draggers” was an excerpt from this chapter. We have created “Working With Fire” for your enjoyment, as our “Return to the Community”. (It contains historical photos, including Cessna Aircraft Company photos, that have been re-printed with permission.) “Working With Fire”, and all contents thereof, may be reproduced for the enjoyment of others. However, all copyrights are reserved. No part of the presentation, or the entirety of, may be sold, bartered, or have any financial negotiations associated with the distribution of its contents. We hope you enjoy “Working With Fire” as much as we enjoyed putting it together for you! Please visit us at our new website, www.mortbrown.info . Sincerely, Mort & Sharon Brown Wichita, Kansas [email protected] DISCLAIMER: Cessna Aircraft Company has not sponsored nor endorsed any part of this presentation. “Working With Fire” (Mort’s Aviation Experiences & History) Mort Brown Photo by Don Wiley By Mort & Sharon Brown Copyrighted 2007 (All Rights Reserved) TITLE PAGE TITLE PAGE 1. Cover Letter………………………………………………………………..1 2. Cover Page ………………………………..……………………….………2 3. Title Page ……..………………………………………………….………..3 4. Dedication………………..…………………………………………….…..4 5. Acknowledgements…..…………………………………………………..5 - 6 6. -

C172 Flight Manual Download

c172 flight manual download File Name: c172 flight manual download.pdf Size: 1505 KB Type: PDF, ePub, eBook Category: Book Uploaded: 14 May 2019, 23:29 PM Rating: 4.6/5 from 615 votes. Status: AVAILABLE Last checked: 7 Minutes ago! In order to read or download c172 flight manual download ebook, you need to create a FREE account. Download Now! eBook includes PDF, ePub and Kindle version ✔ Register a free 1 month Trial Account. ✔ Download as many books as you like (Personal use) ✔ Cancel the membership at any time if not satisfied. ✔ Join Over 80000 Happy Readers Book Descriptions: We have made it easy for you to find a PDF Ebooks without any digging. And by having access to our ebooks online or by storing it on your computer, you have convenient answers with c172 flight manual download . To get started finding c172 flight manual download , you are right to find our website which has a comprehensive collection of manuals listed. Our library is the biggest of these that have literally hundreds of thousands of different products represented. Home | Contact | DMCA Book Descriptions: c172 flight manual download This book is a property of Cessna Aircraft Company and all rights go to them. You can download the pdf version of the book here. POH Section 1, General Information. We presented the utter. Now, our extensive product Commercial vehicles With Specifications and Photos Page 2. Item Code Pipe Capacity line and broad geographical. Kindle Cloud Reader Read. Transport a crawler excavator or wheel loader with 2017 5 Fri, June 23, 2017 2 Runs for Doosan Construction Equipment, units 172 problems. -

Textron Inc. Annual Report 2018

Textron Inc. Annual Report 2018 Form 10-K (NYSE:TXT) Published: February 15th, 2018 PDF generated by stocklight.com UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K [ x ] ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 30, 2017 or [ ] TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to . Commission File Number 1-5480 Textron Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 05-0315468 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 40 Westminster Street, Providence, RI 02903 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) Registrants Telephone Number, Including Area Code: (401) 421-2800 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of Each Exchange on Which Title of Each Class Registered Common Stock par value $0.125 New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ü No___ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes No ü Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

•Flying a Helio Courier •Airventure Awards •Vin Fiz Straight & Level Vintage Airplane GEOFF ROBISON STAFF VAA PRESIDENT, EAA 268346, VAA 12606 EAA Publisher

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2013 Super CUB One •Flying a Helio Courier •AirVenture Awards •Vin Fiz Straight & Level Vintage Airplane GEOFF ROBISON STAFF VAA PRESIDENT, EAA 268346, VAA 12606 EAA Publisher . .Jack J . Pelton, . .Chairman of the Board Editor-in-Chief . J . Mac McClellan Editor . Jim Busha Oshkosh 2013 is now . [email protected] VAA Executive Administrator Max Platts in the history books 920-426-6110 . [email protected] Advertising Director . Katrina Bradshaw 202-577-9292 . [email protected] Uppermost in the minds of many of our members today is the Advertising Manager . Sue Anderson recent FAA action to assess operational fees for air traffic control ser- 920-426-6127 . [email protected] vices at AirVenture Oshkosh. To me, this is a particularly troublesome Art Director . Livy Trabbold development that arises out of the issues relevant to sequestration as VAA, PO Box 3086, Oshkosh, WI 54903 it was applied to the FAA. Early on in this debate Congress responded Website: www.VintageAircraft.org by exempting the FAA from the budget cuts that sequestration im- Email: [email protected] posed on them. Of course, we all wrongly assumed that this would eliminate the then “proposed” fees placed on AirVenture Oshkosh. This very burdensome level of fees is really an unfair tax on a signifi- cant aviation event that has been leveled by the FAA without any authority whatsoever to act in this manner. My real purpose here is to merely reach out to our membership and encourage you all to TM continue to communicate to your representatives in Washington our strong displeasure with this unauthorized attack on general aviation. -

PDF Version April May 2008

MIDWEST FLYER MAGAZINE APRIL/MAY 2008 Celebrating 30 Years Published For & By The Midwest Aviation Community Since 1978 midwestflyer.com Cessna Sales Team Authorized Representative for: J.A. Aero Aircraft Sales IL, WI & Upper MI Caravan Sales for: 630-584-3200 IL, WI & MO Largest Full-Service Cessna Dealer in Midwest See the Entire Cessna Propeller Line – From SkyCatcher Thru Caravan Delivery Positions on New Cessna 350 & 400! Scott Fank – Email: [email protected] Chicago’s DuPage Airport (DPA) Dave Kay – Email: [email protected] +2%.+ 6!./$%#+ Visit Us Online at (630) 584-3200 www.jaaero.com (630) 613-8408 Fax Upgrade or Replace? WWAASAAS isis Here!Here! The Choice is Yours Upgrade Your Unit OR Exchange for Brand New New Hardware / New Software / New 2 Year Warranty Call J.A. Air Center today to discuss which is the best option for you. Illinois 630-584-3200 + Toll Free 800-323-5966 Email [email protected] & [email protected] Web www.jaair.com * Certain Conditions= FBOand Services Restrictions Apply Avionics Sales and Service Instrument Sales and Service Piston and Turbine Maintenance Mail Order Sales Cessna Sales Team Authorized Representative for: J.A. Aero Aircraft Sales IL, WI & Upper MI VOL. 30, NO. 3 ISSN:0194-5068 Caravan Sales for: 630-584-3200 IL, WI & MO CONTENTS ON THE COVER: “Touch & Go At Sunset.” Photo taken at Middleton Municipal Airport – Morey Field (C29), Middleton, Wis. by Geoff Sobering MIDWEST FLYER MAGAZINE APRIL/MAY 2008 COLUMNS AOPA Great Lakes Regional Report - by Bill Blake ........................................................................ 24 Aviation Law - by Greg Reigel ......................................................................................................... 26 Largest Full-Service Cessna Dialogue - by Dave Weiman .......................................................................................................... -

Newsletter 0704-2.Pub

Fourth Quarter (Oct - Dec) 2007 Volume 20, Number 4 The Newsletter of the War Eagles Air Museum Editorial s subjects of in-depth articles for the newsletter of a Museum ded- A icated primarily to World War II and Korean War military “warbirds,” the two aircraft covered in this issue of Plane Talk may seem a little out of place. What do the diminutive, unarmed, easy-to-fly Piper Super Cub and Cessna 140 civilian aircraft have to do with the large, heavy, imposing, armed-to-the-teeth “warbirds” that make up most of the War Eagles Air Museum collection? The answer is, “Everything.” The histories of Piper Aircraft Corp- oration and Cessna Aircraft Company be- gan in the earliest days of American avia- tion. Aircraft that rolled off of these com- panies’ assembly lines inspired dreams of flight in countless wide-eyed boys—and, no doubt, some girls as well. Many of these nascent pilots joined the Army, Na- vy or Marines in World War II and went S The Museum’s “new” 1954 Piper PA-18 Super Cub, piloted by Terry Sunday (f) and on to become America’s fighter, bomber Featured Aircraft Chief Pilot Gene Dawson (r), flies over the and transport pilots. As you read this is- irplanes are very much like peo- New Mexico desert. Photo: Chuck Crepas. sue, keep in mind that the docile little air- Cessna 172N photo plane pilot: Carl Wright. planes that Mr. Piper and Mr. Cessna cre- ple. Each one has a distinct per- ated, while they may differ greatly from A sonality. -

Form 10-K Textron Inc

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K [ x ] ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 29, 2018 or [ ] TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to . Commission File Number 1-5480 Textron Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 05-0315468 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 40 Westminster Street, Providence, RI 02903 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) Registrant’s Telephone Number, Including Area Code: (401) 421-2800 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Common Stock — par value $0.125 New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicat e by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ü No___ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes No ü Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days.