Anatomy of a Public Inquiry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manitoba Police Boards: Policy and Procedure

2018 Manitoba Police Boards: Policy and Procedure Manitoba Police Commission 8/1/2018 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Chapter 2: Roles and Responsibilities of Policing Officials and Agencies ....................................................... 7 2.1 Role of the Minister of Justice ................................................................................................................ 8 2.2 Role of the Director of Policing .............................................................................................................. 8 2.3 Role of the Manitoba Police Commission .............................................................................................. 8 2.4 Role of Police Board................................................................................................................................ 8 2.5 Role of Municipal Council ....................................................................................................................... 9 2.6 Role of Police Chief ................................................................................................................................. 9 2.7 Role of Police Officer ............................................................................................................................. -

Alternative North Americas: What Canada and The

ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS What Canada and the United States Can Learn from Each Other David T. Jones ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20004 Copyright © 2014 by David T. Jones All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of author’s rights. Published online. ISBN: 978-1-938027-36-9 DEDICATION Once more for Teresa The be and end of it all A Journey of Ten Thousand Years Begins with a Single Day (Forever Tandem) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Borders—Open Borders and Closing Threats .......................................... 12 Chapter 2 Unsettled Boundaries—That Not Yet Settled Border ................................ 24 Chapter 3 Arctic Sovereignty—Arctic Antics ............................................................. 45 Chapter 4 Immigrants and Refugees .........................................................................54 Chapter 5 Crime and (Lack of) Punishment .............................................................. 78 Chapter 6 Human Rights and Wrongs .................................................................... 102 Chapter 7 Language and Discord .......................................................................... -

Benefits DID YOU FILE YOUR INCOME TAX? Even If You Make No Money, You Should File a Tax Return Each Year

FOR MANITOBA HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS: A TOOL TO ADDRESS povertY GET YOUR BENEFITS DID YOU FILE YOUR INCOME TAX? Even if you make no money, you should file a tax return each year. If you do not file your taxes you CANNOT get government benefits such as: RESOURCES Federal Income Tax Credits: GST Credit DID YOU FILE YOUR INCOME TAX? ......................................3 This is a tax-free quarterly payment that helps individuals/families with low or modest incomes to offset all or part of the GST or HST they pay. Employment & INCOME Assistance ........................ 4-5 Working Income Tax Benefit This is a refundable tax credit for working people with low incomes. FAMILIES WITH CHILDREN ................................................6 Provincial (MB) Income Tax Credits: PERSONS LIVING WITH DISABILITIES ................................7 Personal Tax Credit – a credit for low income Manitobans and their dependents. Education Property Tax Credit – for those who pay rent or property taxes in Manitoba. Seniors may qualify for additional amounts. SENIORS AND 55 PLUS .....................................................8 Primary Caregiver Tax Credit – for people who provide care and support to family members, friends or neighbours who need help in their home. ADDICTION Services ......................................................9 Tuition Fee Income Tax Rebate – for graduates of post-secondary programs who live and pay taxes in Manitoba. Health NEEDS ......................................................... 10-11 Child Tax Benefits (CTB): These are monthly payments to help support your children. You may have applied MENTAL Health ............................................................12 for child benefits when you asked for your child’s birth certificate. If you haven’t applied, you can do this by completing the form RC66-Canada Child Benefits FIRST Nations RESOURCES ...........................................13 Application and sending it to Canada Revenue. -

Police Boards

Manitoba Justice ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• Police Boards Board Members Members Carolyn Eva Penner, Altona Susan J. Meighen, Brandon Reginald Atkinson, Brandon Linda Doerksen, Morden Lorrie Dyer, Rivers Angela Temple, Dugald (bil) Anni Markmann, Ste. Anne Mandate: The Police Boards’ mandate, as outlined in the Police Services Act is to provide civilian governance respecting the enforcement of law, the maintenance of the public peace and the prevention of crime in the (insert Town name here), and to provide the administrative direction and organization required to provide an adequate and effective police service in the town or city. Authority: Police Services Act Responsibilities: As outlined in section 27 of the Police Services Act, the Police Boards’ responsibilities include consulting with the police chief to establish priorities and objectives for the police service; establishing policies for the effective management of the police service; directing the police chief and monitoring his/her performance; and performing any other prescribed duties. More specifically, the Police Board fulfills a community purpose. It ensures that community needs and values are reflected in policing priorities, objectives, programs and strategies. It acts as a liaison between the community and the respective town/city Police Service to ensure that services are delivered in a manner consistent with community needs, values, and expectations. The board also ensures that the police chief establishes programs and strategies to implement the priorities and objectives established by the board. Membership: Altona: Five members, with four appointed by the Town of Altona and one appointed through provincial order in council. Those appointed by the town are comprised as follows: a) Two members of Altona town council b) Two community members appointed by Altona town council Police Boards 2 Brandon: Seven members, with five appointed by the City of Brandon and one appointed through provincial order in council. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CHRETIEN LEGACY Introduction .................................................. i The Chr6tien Legacy R eg W hitaker ........................................... 1 Jean Chr6tien's Quebec Legacy: Coasting Then Stickhandling Hard Robert Y oung .......................................... 31 The Urban Legacy of Jean Chr6tien Caroline Andrew ....................................... 53 Chr6tien and North America: Between Integration and Autonomy Christina Gabriel and Laura Macdonald ..................... 71 Jean Chr6tien's Continental Legacy: From Commitment to Confusion Stephen Clarkson and Erick Lachapelle ..................... 93 A Passive Internationalist: Jean Chr6tien and Canadian Foreign Policy Tom K eating ......................................... 115 Prime Minister Jean Chr6tien's Immigration Legacy: Continuity and Transformation Yasmeen Abu-Laban ................................... 133 Renewing the Relationship With Aboriginal Peoples? M ichael M urphy ....................................... 151 The Chr~tien Legacy and Women: Changing Policy Priorities With Little Cause for Celebration Alexandra Dobrowolsky ................................ 171 Le Petit Vision, Les Grands Decisions: Chr~tien's Paradoxical Record in Social Policy M ichael J. Prince ...................................... 199 The Chr~tien Non-Legacy: The Federal Role in Health Care Ten Years On ... 1993-2003 Gerard W . Boychuk .................................... 221 The Chr~tien Ethics Legacy Ian G reene .......................................... -

Transparency International Canada Inc

Transparency International Canada Inc. COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS ON THE MECHANISM FOR FOLLOW-UP ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE INTER-AMERICAN CONVENTION AGAINST CORRUPTION REPORT ON THE IMPLEMENTATION IN CANADA OF THE CONVENTION PROVISIONS SELECTED FOR REVIEW IN THE THIRD ROUND, AND ON FOLLOW-UP TO THE RECOMMENDATIONS FORMULATED TO THAT COUNTRY IN PREVIOUS ROUNDS. I - INTRODUCTION 1. Contents of the Report a. This report presents, first, a review of the implementation in Canada of the Inter- American Convention against Corruption selected by the Committee of Experts of the Follow-up Mechanism (MESICIC) for review in the third round: Article III, paragraphs 7 and 10, and Articles VIII, IX, X and XIII. b. Second, the report will examine the follow up to the recommendations that were formulated by the MESICIC Committee of Experts in the previous rounds, which are contained in the reports adopted by the Committee and published at the following web pages: i. http://www.oas.org/juridico/english/mec_rep_can.pdf (First Round) ii. http://www.oas.org/juridico/english/mesicic_II_inf_can_en.pdf (Second Round) c. This report was prepared primarily based on inputs from members including Directors of Transparency International Canada. The Directors of Transparency International Canada and its members comprise an extensive resource of experience. There is a significant representation from members of the legal profession engaged in international trade practices and from the accountancy profession – in particular those engaged in forensic practices. There is representation from academics and from industry. d. Mr. Thomas C. Marshall, Q.C., is the Vice-chair and Director of Transparency International Canada, and Chair of the International Development Committee of 1 the Canadian Bar Association. -

The Mulroney-Schreiber Affair - Our Case for a Full Public Inquiry

HOUSE OF COMMONS CANADA THE MULRONEY-SCHREIBER AFFAIR - OUR CASE FOR A FULL PUBLIC INQUIRY Report of the Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics Paul Szabo, MP Chair APRIL, 2008 39th PARLIAMENT, 2nd SESSION The Speaker of the House hereby grants permission to reproduce this document, in whole or in part for use in schools and for other purposes such as private study, research, criticism, review or newspaper summary. Any commercial or other use or reproduction of this publication requires the express prior written authorization of the Speaker of the House of Commons. If this document contains excerpts or the full text of briefs presented to the Committee, permission to reproduce these briefs, in whole or in part, must be obtained from their authors. Also available on the Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire: http://www.parl.gc.ca Available from Communication Canada — Publishing, Ottawa, Canada K1A 0S9 THE MULRONEY-SCHREIBER AFFAIR - OUR CASE FOR A FULL PUBLIC INQUIRY Report of the Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics Paul Szabo, MP Chair APRIL, 2008 39th PARLIAMENT, 2nd SESSION STANDING COMMITTEE ON ACCESS TO INFORMATION, PRIVACY AND ETHICS Paul Szabo Pat Martin Chair David Tilson Liberal Vice-Chair Vice-Chair New Democratic Conservative Dean Del Mastro Sukh Dhaliwal Russ Hiebert Conservative Liberal Conservative Hon. Charles Hubbard Carole Lavallée Richard Nadeau Liberal Bloc québécois Bloc québécois Glen Douglas Pearson David Van Kesteren Mike Wallace Liberal Conservative Conservative iii OTHER MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT WHO PARTICIPATED Bill Casey John Maloney Joe Comartin Hon. Diane Marleau Patricia Davidson Alexa McDonough Hon. Ken Dryden Serge Ménard Hon. -

Policing and Public Safety Strategy

Manitoba’s Policing and May 2019 Public Safety Strategy Keeping Manitobans safe through collaboration, criminal intelligence and provincial leadership. Manitoba’s Policing and Public Safety Strategy Minister’s Message On March 9, 2018, the Manitoba government announced the Criminal Justice System Modernization Strategy (CJSM), following an internal review of Manitoba’s criminal justice system. The CJSM is a four-point strategy. It emphasizes crime prevention. It targets resources for serious criminal cases. It more effectively uses restorative justice. And it supports the responsible reintegration of offenders. The goal of the CJSM is to transform the way we deal with complex issues related to the administration of justice in our province. It is designed to help create safe communities and ensure timely access to justice for all Manitobans. We have made significant progress since the launch of the CJSM. Criminal cases are moving more quickly, fewer people are in custody, and where appropriate, more matters are being referred to restorative justice to enhance accountability and reduce reliance on incarceration before trial. Manitoba is also taking action to improve road safety and reduce the number of fatal collisions on our roads. New legislation will create tougher sanctions for impaired drivers, utilizing a more efficient administrative system that allows police to remain on the road to apprehend more impaired drivers and dedicate more of their resources to arresting violent offenders. Manitoba Justice has already taken concrete actions to address many of the challenges in our criminal justice system. However, while early results show promise, challenges remain and there is much more to do. -

The Political Legitimacy of Cabinet Secrecy

51 The Political Legitimacy of Cabinet Secrecy Yan Campagnolo* La légitimité politique du secret ministériel La legitimidad política del secreto ministerial A legitimidade política do segredo ministerial 内阁机密的政治正当性 Résumé Abstract Dans le système de gouvernement In the Westminster system of re- responsable de type Westminster, les sponsible government, constitutional conventions constitutionnelles protègent conventions have traditionally safe- traditionnellement le secret des délibéra- guarded the secrecy of Cabinet proceed- tions du Cabinet. Dans l’ère moderne, où ings. In the modern era, where openness l’ouverture et la transparence sont deve- and transparency have become funda- nues des valeurs fondamentales, le secret mental values, Cabinet secrecy is now ministériel est désormais perçu avec scep- looked upon with suspicion. The justifi- ticisme. La justification et la portée de la cation and scope of Cabinet secrecy re- règle font l’objet de controverses. Cet ar- main contentious. The aim of this article ticle aborde ce problème en expliquant les is to address this problem by explaining raisons pour lesquelles le secret ministériel why Cabinet secrecy is, within limits, es- est, à l’intérieur de certaines limites, essen- sential to the proper functioning of our tiel au bon fonctionnement de notre sys- system of government. Based on the rele- * Assistant Professor, Common Law Section, University of Ottawa. This article is based on the first chapter of a dissertation which was submitted in connection with fulfilling the requirements for a doctoral degree in law at the University of Toronto. The research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. For helpful comments on earlier versions, I am indebted to Kent Roach, David Dyzenhaus, Hamish Stewart, Peter Oliver and the anonymous reviewers of the Revue juridique Thémis. -

Manitoba Government Job Opportunities Feb 25, 2021 No

Manitoba Government Job Opportunities Feb 25, 2021 No. 1031 Page 1 of 4 For complete information on these job opportunities, please visit our website at: http://www.gov.mb.ca/govjobs Employment Equity is a factor in selection. Applicants are requested to indicate in their covering letter, resumé and/or application if they are from any of the following groups: women, Aboriginal people, visible minorities and persons with a disability. Advertisement No. 37118 - Protective Services Officer, BG Protective Services Officer, Term/full-time, Protective Services, Community Safety, The Pas MB, Thompson MB, Portage la Prairie MB, Brandon MB Department(s): Manitoba Justice Salary(s): BG $17.86 - $20.77 per hour Closing Date: March 05, 2021 Apply To: Advertisement No. 37118, Manitoba Justice, Human Resource Services, 1130-405 Broadway, Winnipeg, MB, MB, R3C 3L6, Ph: 204-945-3204, Fax: 204-948-7373, Email: [email protected] Advertisement No. 37164 - Administrative Secretary, AY3 Administrative Secretary 3, Regular/full-time, Public Utilities Board, Winnipeg MB Department(s): Manitoba Finance Salary(s): AY3 $41,136.00 - $47,018.00 per year Closing Date: March 07, 2021 Apply To: Advertisement No. 37164, Manitoba Finance, Human Resource Services, 600-155 Carlton Street, Winnipeg, MB, MB, R3C 3H8, Ph: 204-945-8819, Fax: 204-948-3382, Email: [email protected] Advertisement No. 37209 - Marine Maintenance Superintendent, CU2 Construction Supervisor 2, Regular/full- time, Northern Airports and Marine Operations, Engineering and Operations, Selkirk MB Department(s): Manitoba Infrastructure Salary(s): CU2 $63,548.00 - $73,774.00 per year Closing Date: March 07, 2021 Apply To: Advertisement No. -

Integration Guide CDE.Pdf

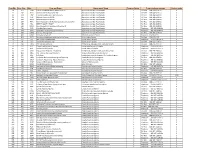

Prog Nbr Error Clue Abbr Program Name Department Name Program Active Program phone number Contact code 10 159 PFRA Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Y Toll-Free 800-282-6249 Ext 0 11 160 NISA Farm Income Directorate (FIPD) Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Y Toll-Free 800-282-6249 Ext 0 12 161 TRSP Tripartite Stabilization / Special Grains Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Y Toll-Free 800-282-6249 Ext 0 13 162 PGAP Advance Payments (CWB) Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Y Toll-Free 800-282-6249 Ext 0 14 163 APCA Advance Payments (FGPD) Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Y Toll-Free 800-282-6249 Ext 0 15 164 FIMC Farm Improvement & Marketing Cooperative Loans Act Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Y Toll-Free 800-282-6249 Ext 0 16 165 HILL WGTPP / AASPP / HILLRP Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Y Toll-Free 800-282-6249 Ext 0 17 166 FSAM Farm Support and Adjustment Measures II Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Y Toll-Free 800-282-6249 Ext 0 18 713 CFIP Canadian Farm Income Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Y Telephone 800-282-6249 Ext 0 19 714 AIDA Agricultural Income Disaster Assistance Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Y Telephone 800-282-6249 Ext 0 20 788 AGRM Revenue Management Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Y Toll-Free 800-282-6249 Ext 0 21 900 NRSO Salary overpayments Natural Resources Canada N Telephone 343-292-6715 0 30 901 PSED Recovery of employee debts due to the Crown Public Safety Canada N Toll-Free 800-830-3118 1 50 127 FAIT SMFR Accounts Receivable Global Affairs Canada Y Telephone 343-203-8004 -

Manitoba Justice Annual Report 2019

Manitoba Justice Annual Report 2019 - 2020 This publication is available in alternate formats, upon request, by contacting: Manitoba Justice Administration and Finance Room 1110-405 Broadway Winnipeg, MB R3C 3L6 Phone: 204-945-4378 Fax: 204-945-6692 Email: [email protected] Electronic format: https://www.gov.mb.ca/justice/publications/annualreports/index.html La présente publication est accessible à l'adresse suivante : http://www.gov.mb.ca/justice/publications/annualreports/index.fr.html Veuillez noter que la version intégrale du rapport n'existe qu'en anglais. Nous vous invitons toutefois à consulter la lettre d'accompagnement en français qui figure en début du document. ATTORNEY GENERAL MINISTER OF JUSTICE Room 104 Legislacivc Building Winnipeg, Manitoba R3C 0V8 CANADA Her Honour the Honourable Janice C. Filmon, C.M., O.M. Lieutenant Governor of Manitoba Room 234 Legislative Building Winnipeg MB R3C OV8 May it Please Your Honour: I have the privilege of presenting, for the information of Your Honour, the Annual Report of Manitoba Justice, for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2020. Respectfully submitted, &f(� Honourable Cliff Cullen Minister of Justice Attorney General have included the expanded use of technology and improvement of existing technological infrastructure across the department, and expanded remote service delivery and work arrangements. As the pandemic continues, additional challenges and responses will emerge. I am confident that the Department will meet those challenges and develop, with our justice system partners, innovative and effective responses. I conclude by again acknowledging the tremendous efforts of our staff and of our justice system partners. Their exceptional innovation, dedication and collaboration assure me that together we will overcome the challenges we will face.