Archived Content Contenu Archivé

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manitoba Police Boards: Policy and Procedure

2018 Manitoba Police Boards: Policy and Procedure Manitoba Police Commission 8/1/2018 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Chapter 2: Roles and Responsibilities of Policing Officials and Agencies ....................................................... 7 2.1 Role of the Minister of Justice ................................................................................................................ 8 2.2 Role of the Director of Policing .............................................................................................................. 8 2.3 Role of the Manitoba Police Commission .............................................................................................. 8 2.4 Role of Police Board................................................................................................................................ 8 2.5 Role of Municipal Council ....................................................................................................................... 9 2.6 Role of Police Chief ................................................................................................................................. 9 2.7 Role of Police Officer ............................................................................................................................. -

Benefits DID YOU FILE YOUR INCOME TAX? Even If You Make No Money, You Should File a Tax Return Each Year

FOR MANITOBA HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS: A TOOL TO ADDRESS povertY GET YOUR BENEFITS DID YOU FILE YOUR INCOME TAX? Even if you make no money, you should file a tax return each year. If you do not file your taxes you CANNOT get government benefits such as: RESOURCES Federal Income Tax Credits: GST Credit DID YOU FILE YOUR INCOME TAX? ......................................3 This is a tax-free quarterly payment that helps individuals/families with low or modest incomes to offset all or part of the GST or HST they pay. Employment & INCOME Assistance ........................ 4-5 Working Income Tax Benefit This is a refundable tax credit for working people with low incomes. FAMILIES WITH CHILDREN ................................................6 Provincial (MB) Income Tax Credits: PERSONS LIVING WITH DISABILITIES ................................7 Personal Tax Credit – a credit for low income Manitobans and their dependents. Education Property Tax Credit – for those who pay rent or property taxes in Manitoba. Seniors may qualify for additional amounts. SENIORS AND 55 PLUS .....................................................8 Primary Caregiver Tax Credit – for people who provide care and support to family members, friends or neighbours who need help in their home. ADDICTION Services ......................................................9 Tuition Fee Income Tax Rebate – for graduates of post-secondary programs who live and pay taxes in Manitoba. Health NEEDS ......................................................... 10-11 Child Tax Benefits (CTB): These are monthly payments to help support your children. You may have applied MENTAL Health ............................................................12 for child benefits when you asked for your child’s birth certificate. If you haven’t applied, you can do this by completing the form RC66-Canada Child Benefits FIRST Nations RESOURCES ...........................................13 Application and sending it to Canada Revenue. -

Police Boards

Manitoba Justice ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• Police Boards Board Members Members Carolyn Eva Penner, Altona Susan J. Meighen, Brandon Reginald Atkinson, Brandon Linda Doerksen, Morden Lorrie Dyer, Rivers Angela Temple, Dugald (bil) Anni Markmann, Ste. Anne Mandate: The Police Boards’ mandate, as outlined in the Police Services Act is to provide civilian governance respecting the enforcement of law, the maintenance of the public peace and the prevention of crime in the (insert Town name here), and to provide the administrative direction and organization required to provide an adequate and effective police service in the town or city. Authority: Police Services Act Responsibilities: As outlined in section 27 of the Police Services Act, the Police Boards’ responsibilities include consulting with the police chief to establish priorities and objectives for the police service; establishing policies for the effective management of the police service; directing the police chief and monitoring his/her performance; and performing any other prescribed duties. More specifically, the Police Board fulfills a community purpose. It ensures that community needs and values are reflected in policing priorities, objectives, programs and strategies. It acts as a liaison between the community and the respective town/city Police Service to ensure that services are delivered in a manner consistent with community needs, values, and expectations. The board also ensures that the police chief establishes programs and strategies to implement the priorities and objectives established by the board. Membership: Altona: Five members, with four appointed by the Town of Altona and one appointed through provincial order in council. Those appointed by the town are comprised as follows: a) Two members of Altona town council b) Two community members appointed by Altona town council Police Boards 2 Brandon: Seven members, with five appointed by the City of Brandon and one appointed through provincial order in council. -

Policing and Public Safety Strategy

Manitoba’s Policing and May 2019 Public Safety Strategy Keeping Manitobans safe through collaboration, criminal intelligence and provincial leadership. Manitoba’s Policing and Public Safety Strategy Minister’s Message On March 9, 2018, the Manitoba government announced the Criminal Justice System Modernization Strategy (CJSM), following an internal review of Manitoba’s criminal justice system. The CJSM is a four-point strategy. It emphasizes crime prevention. It targets resources for serious criminal cases. It more effectively uses restorative justice. And it supports the responsible reintegration of offenders. The goal of the CJSM is to transform the way we deal with complex issues related to the administration of justice in our province. It is designed to help create safe communities and ensure timely access to justice for all Manitobans. We have made significant progress since the launch of the CJSM. Criminal cases are moving more quickly, fewer people are in custody, and where appropriate, more matters are being referred to restorative justice to enhance accountability and reduce reliance on incarceration before trial. Manitoba is also taking action to improve road safety and reduce the number of fatal collisions on our roads. New legislation will create tougher sanctions for impaired drivers, utilizing a more efficient administrative system that allows police to remain on the road to apprehend more impaired drivers and dedicate more of their resources to arresting violent offenders. Manitoba Justice has already taken concrete actions to address many of the challenges in our criminal justice system. However, while early results show promise, challenges remain and there is much more to do. -

Manitoba Government Job Opportunities Feb 25, 2021 No

Manitoba Government Job Opportunities Feb 25, 2021 No. 1031 Page 1 of 4 For complete information on these job opportunities, please visit our website at: http://www.gov.mb.ca/govjobs Employment Equity is a factor in selection. Applicants are requested to indicate in their covering letter, resumé and/or application if they are from any of the following groups: women, Aboriginal people, visible minorities and persons with a disability. Advertisement No. 37118 - Protective Services Officer, BG Protective Services Officer, Term/full-time, Protective Services, Community Safety, The Pas MB, Thompson MB, Portage la Prairie MB, Brandon MB Department(s): Manitoba Justice Salary(s): BG $17.86 - $20.77 per hour Closing Date: March 05, 2021 Apply To: Advertisement No. 37118, Manitoba Justice, Human Resource Services, 1130-405 Broadway, Winnipeg, MB, MB, R3C 3L6, Ph: 204-945-3204, Fax: 204-948-7373, Email: [email protected] Advertisement No. 37164 - Administrative Secretary, AY3 Administrative Secretary 3, Regular/full-time, Public Utilities Board, Winnipeg MB Department(s): Manitoba Finance Salary(s): AY3 $41,136.00 - $47,018.00 per year Closing Date: March 07, 2021 Apply To: Advertisement No. 37164, Manitoba Finance, Human Resource Services, 600-155 Carlton Street, Winnipeg, MB, MB, R3C 3H8, Ph: 204-945-8819, Fax: 204-948-3382, Email: [email protected] Advertisement No. 37209 - Marine Maintenance Superintendent, CU2 Construction Supervisor 2, Regular/full- time, Northern Airports and Marine Operations, Engineering and Operations, Selkirk MB Department(s): Manitoba Infrastructure Salary(s): CU2 $63,548.00 - $73,774.00 per year Closing Date: March 07, 2021 Apply To: Advertisement No. -

Integration Guide CDE.Pdf

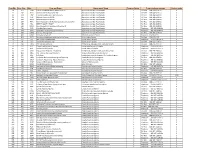

Prog Nbr Error Clue Abbr Program Name Department Name Program Active Program phone number Contact code 10 159 PFRA Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Y Toll-Free 800-282-6249 Ext 0 11 160 NISA Farm Income Directorate (FIPD) Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Y Toll-Free 800-282-6249 Ext 0 12 161 TRSP Tripartite Stabilization / Special Grains Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Y Toll-Free 800-282-6249 Ext 0 13 162 PGAP Advance Payments (CWB) Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Y Toll-Free 800-282-6249 Ext 0 14 163 APCA Advance Payments (FGPD) Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Y Toll-Free 800-282-6249 Ext 0 15 164 FIMC Farm Improvement & Marketing Cooperative Loans Act Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Y Toll-Free 800-282-6249 Ext 0 16 165 HILL WGTPP / AASPP / HILLRP Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Y Toll-Free 800-282-6249 Ext 0 17 166 FSAM Farm Support and Adjustment Measures II Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Y Toll-Free 800-282-6249 Ext 0 18 713 CFIP Canadian Farm Income Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Y Telephone 800-282-6249 Ext 0 19 714 AIDA Agricultural Income Disaster Assistance Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Y Telephone 800-282-6249 Ext 0 20 788 AGRM Revenue Management Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Y Toll-Free 800-282-6249 Ext 0 21 900 NRSO Salary overpayments Natural Resources Canada N Telephone 343-292-6715 0 30 901 PSED Recovery of employee debts due to the Crown Public Safety Canada N Toll-Free 800-830-3118 1 50 127 FAIT SMFR Accounts Receivable Global Affairs Canada Y Telephone 343-203-8004 -

Manitoba Justice Annual Report 2019

Manitoba Justice Annual Report 2019 - 2020 This publication is available in alternate formats, upon request, by contacting: Manitoba Justice Administration and Finance Room 1110-405 Broadway Winnipeg, MB R3C 3L6 Phone: 204-945-4378 Fax: 204-945-6692 Email: [email protected] Electronic format: https://www.gov.mb.ca/justice/publications/annualreports/index.html La présente publication est accessible à l'adresse suivante : http://www.gov.mb.ca/justice/publications/annualreports/index.fr.html Veuillez noter que la version intégrale du rapport n'existe qu'en anglais. Nous vous invitons toutefois à consulter la lettre d'accompagnement en français qui figure en début du document. ATTORNEY GENERAL MINISTER OF JUSTICE Room 104 Legislacivc Building Winnipeg, Manitoba R3C 0V8 CANADA Her Honour the Honourable Janice C. Filmon, C.M., O.M. Lieutenant Governor of Manitoba Room 234 Legislative Building Winnipeg MB R3C OV8 May it Please Your Honour: I have the privilege of presenting, for the information of Your Honour, the Annual Report of Manitoba Justice, for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2020. Respectfully submitted, &f(� Honourable Cliff Cullen Minister of Justice Attorney General have included the expanded use of technology and improvement of existing technological infrastructure across the department, and expanded remote service delivery and work arrangements. As the pandemic continues, additional challenges and responses will emerge. I am confident that the Department will meet those challenges and develop, with our justice system partners, innovative and effective responses. I conclude by again acknowledging the tremendous efforts of our staff and of our justice system partners. Their exceptional innovation, dedication and collaboration assure me that together we will overcome the challenges we will face. -

Association of Manitoba Municipalities Position Paper

ASSOCIATION OF MANITOBA MUNICIPALITIES POSITION PAPER MINISTER OF JUSTICE|CAMERON FRIESEN| MARCH 1, 2021 PRIORITY ITEMS: LOCAL CRIME AND COMMUNITY SAFETY POLICE SERVICES ACT REVIEW REVIEW OF POLICING STRUCTURE & PROVINCIAL FUNDING SUPPORT FOR MUNICIPALITIES PATIENT TRANSFERS UNDER THE MENTAL HEALTH ACT ENFORCEMENT OF WEIGHT RESTRICTIONS The AMM appreciates the This document outlines the AMM’s PARTNERS IN GROWTH opportunity to meet with Minister position and recommendations on a Cameron Friesen and number of important municipal issues The AMM looks forward representatives of Manitoba relevant to the Justice portfolio. to working with the Justice. Province of Manitoba to strengthen provincial- The AMM encourages the Province municipal growth and to consider municipal concerns as partnership well as the effects of funding opportunities. decisions on local communities throughout the budget process. Priority Item #1 Local Crime and Community Safety Issues The AMM recommends the government: ✓ Increase support to police services to address increasing rates of rural crime and help mitigate illicit drug use in local communities. • According to a study by the Angus Reid Institute, half of Canadians (48%) now say that crime has increased in their community over the past five years. The Crime Severity Index (CSI) has also risen for the fifth straight year. • Meanwhile, Manitoba municipalities have been ringing the alarm on increasing crime rates in their communities since the Prairie Provinces are experiencing higher rates of rural crime compared to other areas of the country. • Thus, the AMM welcomes the provincial government seeking feedback from rural Manitoba to help combat rural crime in partnership with municipal officials and stakeholders. -

Department of Justice Canada

THE CHILD-CENTRED FAMILY LAW STRATEGY SUMMATIVE EVALUATION Final Report June 2008 Evaluation Division Office of Strategic Planning and Performance Management TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Context and Purpose of the Summative Evaluation ......................................................... 1 1.2. Organization of the Report................................................................................................ 2 2. BACKGROUND AND DESCRIPTION OF THE STRATEGY........................................ 3 2.1. Issues and Trends in Families........................................................................................... 3 2.2. Family Law and Family Justice Activities in Canada ...................................................... 5 2.3. Description of the Child-centred Family Law Strategy.................................................... 6 2.3.1. Pillars of the Strategy.............................................................................................. 7 2.3.2. CCFLS Governance, Structure and Activities........................................................ 8 2.3.3. Provincial/Territorial Involvement ....................................................................... 10 3. EVALUATION METHODOLOGY ................................................................................... 13 3.1. Evaluation Objectives .................................................................................................... -

Manitoba Justice Is Responsible for the Administration of Civil and Criminal Justice in Manitoba

Annual Report 2011 - 2012 Table of Contents Title Page Introduction 9 Report Structure 9 Vision and Mission 9 Organization Chart 11 Administration, Finance and Justice Innovation 12 Executive Administration Component 12 Minister‟s Salary 12 Executive Support 12 Policy Development and Analysis 13 Operational Administration Component 14 Financial and Administrative Services (includes Justice Innovation) 14 Computer Services 15 Criminal Justice 17 Administration 17 Manitoba Prosecutions Service 17 Provincial Policing 19 Aboriginal and Community Law Enforcement 19 Victim Services 21 Compensation for Victims of Crime 22 Law Enforcement Review Agency 23 Office of the Chief Medical Examiner 23 Criminal Property Forfeiture 24 Manitoba Police Commission 25 Independent Investigation Unit 26 Phoenix Sinclair Inquiry 26 Civil Justice 27 Manitoba Human Rights Commission 27 Legislative Counsel 28 Manitoba Law Reform Commission – Grant 29 Family Law 29 Constitutional Law 30 Legal Aid Manitoba 31 Civil Legal Services 32 The Public Trustee 32 Corrections 33 Corporate Services 34 Adult Corrections 34 Youth Corrections 35 Justice Initiatives Fund – Corrections 37 7 Courts 38 Court Services 39 Winnipeg Courts 40 Regional Courts 41 Judicial Services 42 Sheriff Services 43 Costs Related to Capital Assets 44 Financial Information Section 45 Reconciliation Statement of Printed Vote 45 Expenditure Summary 46 Revenue Summary 53 Five-year Expenditure and Staffing Summary 54 Performance Reporting 58 The Public Interest Disclosure (Whistleblower Protection) Act 65 -

Declaration of Income for Minor Applicants

..................................................................................... Healthy Child Manitoba Office 3rd Floor – 332 Bannatyne Avenue, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada R3A 0E2 T 204-945-1301 F 204-948-2303 Toll-Free 1-888-848-0140 www.manitoba.ca DECLARATION OF INCOME FOR MINOR APPLICANTS PERSONAL INFORMATION: You must be 18 or under and have never filed income tax to use this form. (Please print) Last Name: _________________________ First Name: _____________________ ___ Date of Birth: ________________________ SIN: __________________________ ____ Mailing Address: ________________________ Home telephone: ____________________ Postal Code: __________________ APPLICANT’S DECLARATION: Please check the box that describes your situation. □ I have never worked □ I have worked but made less than $11,809.00 (basic personal income tax exemption by Canada Revenue Agency) I understand that the information contained on this form will be added to my application for Healthy Baby: Manitoba Prenatal Benefits. I consent to Healthy Child Manitoba using this information for the general administration and enforcement of the program. Any other use or any disclosure of this information by Healthy Child Manitoba must be authorized by me or authorized under the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act of Manitoba. I understand that I am not automatically entitled to program consideration and that the Manitoba Prenatal Benefit office will review the information I am providing on this form. The office will decide if program consideration will apply to me. APPLICANT: (Signature is required) Signature: __________________________________ Date: ___________________________ NOTE: It is in your best interest to file income tax, even if you have never worked or made less than the basic exemption. Doing so will create eligibility for other programs such as the National Child Benefit. -

Aboriginal Policing in Manitoba

ABORIGINAL POLICING IN MANITOBA A REPORT TO THE ABORIGINAL JUSTICE IMPLEMENTATION COMMISSION Rick Linden University of Manitoba Donald Clairmont Chris Murphy Dalhousie University 2 SECTION 1 A REVIEW OF CANADIAN POLICING TRENDS AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS FOR ABORIGINAL POLICING IN MANITOBA1. POLICE RESOURCES - TRENDS AND ISSUES 1. Increasing Policing Costs During the 1960s and 1970s, a combination of economic prosperity and increasing crime led governments to dramatically increase the number of police officers in Canada, to raise their salaries, and to supply them with expensive police equipment and technology. This transformed public policing into a well-staffed and expensive public service. By the end of the 1980s, mounting government debt, tax-weary citizens and more fiscally conservative governments began to reverse government spending patterns by reducing or limiting budget increases for public policing. Nevertheless as salary and infrastructure costs increased, the cost of public policing continued to grow, even as overall government spending declined. The rising cost of public policing has made the issue of police funding and service rationalization a focus of increasing political and public debate. Implications for Aboriginal Policing ! Most Aboriginal police services are more costly to operate than their comparable non- Aboriginal counterparts. This higher cost is primarily due to higher staffing levels (Statistics Canada, 1997). Research suggests that most Aboriginal police services 1The analysis for this section of the report is based on a recently completed study of Canadian policing trends conducted for the Police Futures Group of the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police (Murphy 2001). The application of these findings to Aboriginal policing is based on two recent research studies on Aboriginal police and policing in Canada co-authored with D.