Women on Fire: Sati, Consent, and the Revolutionary Subject

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Great Calcutta Killings Noakhali Genocide

1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE 1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE A HISTORICAL STUDY DINESH CHANDRA SINHA : ASHOK DASGUPTA No part of this publication can be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the author and the publisher. Published by Sri Himansu Maity 3B, Dinabandhu Lane Kolkata-700006 Edition First, 2011 Price ` 500.00 (Rupees Five Hundred Only) US $25 (US Dollars Twenty Five Only) © Reserved Printed at Mahamaya Press & Binding, Kolkata Available at Tuhina Prakashani 12/C, Bankim Chatterjee Street Kolkata-700073 Dedication In memory of those insatiate souls who had fallen victims to the swords and bullets of the protagonist of partition and Pakistan; and also those who had to undergo unparalleled brutality and humility and then forcibly uprooted from ancestral hearth and home. PREFACE What prompted us in writing this Book. As the saying goes, truth is the first casualty of war; so is true history, the first casualty of India’s struggle for independence. We, the Hindus of Bengal happen to be one of the worst victims of Islamic intolerance in the world. Bengal, which had been under Islamic attack for centuries, beginning with the invasion of the Turkish marauder Bakhtiyar Khilji eight hundred years back. We had a respite from Islamic rule for about two hundred years after the English East India Company defeated the Muslim ruler of Bengal. Siraj-ud-daulah in 1757. But gradually, Bengal had been turned into a Muslim majority province. -

Conspiracy Rises Again Racial Sympathy and Radical Solidarity Across Empires

Conspiracy Rises Again Racial Sympathy and Radical Solidarity across Empires poulomi saha When in 1925 members of the Jugantar, a secret revolutionary asso- ciation in colonial India, began to conceive of what they believed to be a more effective strategy of anticolonial revolt than that of non- violence promoted at the time by the mainstream Congress Party in Chittagong, they chose for themselves a new name: the Indian Re- publican Army (IRA). In so doing, they explicitly constructed a rev- olutionary genealogy from which their future actions were to draw inspiration, a direct link between the anticolonial revolt in East Ben- gal and the 1916 Easter Uprising in Ireland.1 The 1930 attack on the Chittagong Armory, the first in a series of revolutionary actions tak- en by the IRA, also marked the anniversary of the Irish rebellion. The very language of Irish revolt seeped into the practices of the Indian organization as they smuggled in illegal copies of the writings of Dan Breen and Éamon de Valera and began each meeting with a reading of the Proclamation of the Irish Provisional Government. The ideological and textual kinship between these two anticolo- nial communities and another former holding of the British empire, the United States, illuminates transcolonial circuits that formed a qui parle Vol. 28, No. 2, December 2019 doi 10.1215/10418385-7861837 © 2019 Editorial Board, Qui Parle Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/28/2/307/740477/307saha.pdf by UNIV CA BERKELEY PERIODICALS user on 05 February 2020 308 qui parle december 2019 vol. -

Interim Government ● 2Nd September 1946: Jawaharlal Nehru Was Chosen As the Head of Interim Government

Interim Government ● 2nd September 1946: Jawaharlal Nehru was chosen as the head of interim government. ● It was boycotted by Muslim League. ● After the initial boycott, League joined interim government in the last week of October 1946. ● 5 League members were made ministers in Interim government including Liaquat Ali Khan who was made the Finance Minister. ● 20th Feb 1947: Attlee declared that India would be freed by June 1948 & also announced that Lord Mountbatten would be the last Governor General of India. ● Lord Mountbatten announced Mountbatten plan on 3rd June. Mountbatten Plan ● On 15th August India would be freed. ● If one group of Punjab & Bengal assembly demands for partition, it would be done. ● If partition happened, then there would be boundary commission headed by Radcliffe. ● Princely states had to join either state & were not allowed to remain free. ● Each dominion state will have its own Governor General India Independence Act July 18, 1947 ● The British Parliament ratified the Mountbatten Plan as the "Independence of India Act-1947". The Act was implemented on August 15, 1947. ● The Act provided for the creation of 2 independent dominions of India & Pakistan. ● M.A. Jinnah became the 1st Governor-General of Pakistan. ● India, however, decided to request Lord Mountbatten to continue. ● C Rajagopalachari Revolutionaries Revolutionary Movement q Emerged in 1st decade of 20th century in Bengal (Kolkata) & Maharashtra (Pune) q Anushilan Samiti, Sandhya, Yuganthar were the groups formed in Bengal & Mithra Mela, Abhinav Bharat were formed in Maharashtra Alipore Conspiracy Case ● Also called the Maniktala bomb conspiracy was the trial of a number of revolutionaries in Calcutta under charges of "Waging war against the Government" of the British Raj between May 1908 & May 1909. -

Independence Day

INDEPENDENCE DAY ‘Swaraj is my Birthright and I shall have it’- Bal Gangadhar Tilak India celebrates its Independence Day on 15th August every year. Independence Day reminds us of all the sacrifices that were made by our freedom fighters to make India free from British rule. On 15th August 1947, India was declared independent from British colonialism and became the largest democracy in the world. "Tryst with Destiny" was an English-language speech delivered by Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of India, to the Indian Constituent Assembly in the Parliament, on the eve of India's Independence, towards midnight on 14 August 1947. The speech spoke on the aspects that transcended Indian history. It is considered to be one of the greatest speeches of the 20th century and to be a landmark oration that captures the essence of the triumphant culmination of the Indian independence movement against British colonial rule in India. The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events with the ultimate aim of ending British rule in India. The movement spanned from 1857 to 1947. The first nationalistic revolutionary movement for Indian independence emerged from Bengal. It later took root in the newly formed Indian National Congress with prominent moderate leaders seeking only their fundamental right to appear for Indian Civil Service examinations in British India, as well as more rights (economical in nature) for the people of the soil. The early part of the 20th century saw a more radical approach towards political self-rule proposed by leaders such as the Lal Bal Pal triumvirate, Aurobindo Ghosh and V. -

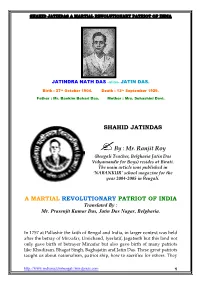

JATINDRA NATH DAS -Alias- JATIN DAS

JATINDRA NATH DAS -alias- JATIN DAS. Birth : 27 th October 1904. Death : 13 th September 1929. Father : Mr. Bankim Behari Das. Mother : Mrs. Suhashini Devi. SHAHID JATINDAS ?By : Mr. Ranjit Roy (Bengali Teacher, Belgharia Jatin Das Vidyamandir for Boys) resides at Birati. The main article was published in ‘NABANKUR’ school magazine for the year 2004-2005 in Bengali. A MARTIAL REVOLUTIONARY PATRIOT OF INDIA Translated By : Mr. Prasenjit Kumar Das, Jatin Das Nagar, Belgharia. In 1757 at Pallashir the faith of Bengal and India, in larger context was held after the betray of Mirzafar, Umichand, Iyerlatif, Jagatseth but this land not only gave birth of betrayer Mirzafar but also gave birth of many patriots like Khudiram, Bhagat Singh, Baghajatin and Jatin Das. These great patriots taught us about nationalism, patriot ship, how to sacrifice for others. They http://www.indianactsinbengali.wordpress.com 1 have tried their best to uphold the head of a unified, independent and united nation. Let us discuss about one of them, Jatin Das and his great sacrifice towards the nation. on 27 th October 1904 Jatin Das (alias Jatindra Nath Das) came to free the nation from the bondage of the British Rulers. He born at his Mother’s house at Sikdar Bagan. He was the first child of father Bankim Behari Das and mother Suhashini Devi. After birth the newborn did not cried for some time then the child cried loudly, it seems that the little one was busy in enchanting the speeches of motherland but when he saw that his motherland is crying for her bondage the little one cant stop crying. -

Oneway Regulation

ONEWAY REGULATION Guard Name Road Name Road New Oneway Oneway Direction Time Remarks Name Stretch Stretch1 BHAWANIPORE Baker Road Biplabi Kanai Entire Entire N-S 08.00- TRAFFIC GUARD Bhattacharya Sarani 20.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Chakraberia Pandit Modan From Sarat Bose From Sarat E-W 08.00- TRAFFIC GUARD Road (North) Mohan Malaviya Rd to B/ Circular Bose Rd to B/ 14.00hrs Sarani Rd Circular Rd BHAWANIPORE Elgin Road Lala Lajpat Rai Entire Entire W-E 14.00- TRAFFIC GUARD Sarani 20.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Harish Mukherjee Entire Entire N-S 14.00- TRAFFIC GUARD Road 21.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Harish Mukherjee Entire Entire S-N 08.00- TRAFFIC GUARD Road 14.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Hasting Park Entire Entire S-N 08.00- Except Sunday TRAFFIC GUARD Road 20.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Justice Ch Entire Entire E-W 14.00- TRAFFIC GUARD Madhab Road 20.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Justice Ch Entire Entire W-E 08.00- TRAFFIC GUARD Madhab Road 14.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Kali Temple Road Entire Entire E-W 08.00- TRAFFIC GUARD 14.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Kalighat Rd Manya Sardar B K Hazra Rd to Hazra Rd to N-S 08.00- TRAFFIC GUARD (portion) Maitra Road Harish Mukherjee Harish 14.00hrs Rd Mukherjee Rd BHAWANIPORE Kalighat Rd Manya Sardar B K Hazra Rd to Hazra Rd to S-N 14.00- TRAFFIC GUARD (portion) Maitra Road Harish Mukherjee Harish 21.00hrs Rd Mukherjee Rd BHAWANIPORE Lee Road O C Ganguly Sarani Entire Entire N-S 08.00- TRAFFIC GUARD 14.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Lee Road O C Ganguly Sarani Entire Entire S-N 14.00- TRAFFIC GUARD 21.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Motilal Nehru N-S 14.00- TRAFFIC GUARD Road 21.00hrs BHAWANIPORE -

Rare– Day 8 Synopsis 2021

RaRe– Day 8 Synopsis 2021 1.There has always been a debate whether freedom was seized by the Indians or power was transferred voluntarily by the British as an act of positive statesmanship. What are your views on this debate? Substantiate. Approach Candidates expected here to argue on both side of the debate with substantive views on issues and events in freedom struggle then in conclusion candidates can write how to save international image and under global pressure transferred power which was a right of Indians. Introduction British decision to quit was partly based on the non - governability of India in the 1940s is beyond doubt. It is difficult to argue that there was consistent policy of devolution of power, which came to its logical culmination in August 1947 through the granting of independence to India. Body • Colonial historiography always believed that Britain will devolve power to Indian subjects but Indians are not politically mature enough for self- government until 1947. • To substantiate their view, they give evidence of 1917 Montague declaration that gradual development of self-governing Institutions with a view to the progressive realisation of responsible governments in India remained objective of British rule in India. • Constitutional reforms after certain interval of time were again part of ultimate aim of self-government to India. • However, it is unliKely that British left India voluntarily in 1947 in pursuance of well-designed policy of decolonisation or that freedom was gift to the Indians. • Constitutional arrangements of 1919 and 1935 were meant to secure British hegemony over the Indian empire through consolidation of control over the central government rather than to make Indians masters of their own affairs. -

Volume9 Issue11(5)

Volume 9, Issue 11(5), November 2020 International Journal of Multidisciplinary Educational Research Published by Sucharitha Publications Visakhapatnam Andhra Pradesh – India Email: [email protected] Website: www.ijmer.in Editorial Board Editor-in-Chief Dr.K. Victor Babu Associate Professor, Institute of Education Mettu University, Metu, Ethiopia EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS Prof. S. Mahendra Dev Prof. Igor Kondrashin Vice Chancellor The Member of The Russian Philosophical Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Society Research, Mumbai The Russian Humanist Society and Expert of The UNESCO, Moscow, Russia Prof.Y.C. Simhadri Vice Chancellor, Patna University Dr. Zoran Vujisiæ Former Director Rector Institute of Constitutional and Parliamentary St. Gregory Nazianzen Orthodox Institute Studies, New Delhi & Universidad Rural de Guatemala, GT, U.S.A Formerly Vice Chancellor of Benaras Hindu University, Andhra University Nagarjuna University, Patna University Prof.U.Shameem Department of Zoology Prof. (Dr.) Sohan Raj Tater Andhra University Visakhapatnam Former Vice Chancellor Singhania University, Rajasthan Dr. N.V.S.Suryanarayana Dept. of Education, A.U. Campus Prof.R.Siva Prasadh Vizianagaram IASE Andhra University - Visakhapatnam Dr. Kameswara Sharma YVR Asst. Professor Dr.V.Venkateswarlu Dept. of Zoology Assistant Professor Sri.Venkateswara College, Delhi University, Dept. of Sociology & Social Work Delhi Acharya Nagarjuna University, Guntur I Ketut Donder Prof. P.D.Satya Paul Depasar State Institute of Hindu Dharma Department of Anthropology Indonesia Andhra University – Visakhapatnam Prof. Roger Wiemers Prof. Josef HÖCHTL Professor of Education Department of Political Economy Lipscomb University, Nashville, USA University of Vienna, Vienna & Ex. Member of the Austrian Parliament Dr.Kattagani Ravinder Austria Lecturer in Political Science Govt. Degree College Prof. -

Government of India Press Santragachi, Howrah

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA PRESS SANTRAGACHI, HOWRAH Information as per Clause(b) of Sub-section 1 of Section 4 of Right to Information Act, 2005 (1) IV (1) bi : The particulars of Govt. of India Press, Santragachi, Howrah, Function and duties. In the year 1863 the Govt. of India decided to establish in Calcutta and Central Press in which administration reports, codes and miscellaneous work could be printed. The Secretariate Printing Offices then in existence confining themselves to current despatches and proceedings. In January, 1864, the orders of the various department of Govt. of India and the Acts and Bills of Governor General’s Council which were formerly published in Calcutta Gazette were transferred to a new publication, the Gazette of India to which was appended a supplement containing official correspondence on the subject of interest of officers and to the general public. In 1876 a system of payment of piece rates was introduced in the composing Branch and subsequently in the distributing, printing and book binding Branches. In June, 1885, the presses of the Home and Public works Department were amalgamated with the Central press. The expansion of the Central Press from a strength of 109 employees, 1863, to that 2114 in 1889 necessiated the provision of additional accommodation pending the building of the Secretariate, the press was located from 1882 to 1885 at 165, Dharmatala Street. On completion of the Secretariate Building the Composing, Machine, press and warehouse, with the administration, Accounts and computing Branches were removed to 8, Hastings Street in 1886. During the World War II, work mostly in Connection with the war increased by leaps and bounds and to cope with the increases of volume of work the minimum strength of additional staff was recruited as a temporary measure and Night Shift was started in the year 1944 with the advent of Independence and consequent expansion of Govt. -

Modern India 1857-1972

mathematics HEALTH ENGINEERING DESIGN MEDIA management GEOGRAPHY EDUCA E MUSIC C PHYSICS law O ART L agriculture O BIOTECHNOLOGY G Y LANGU CHEMISTRY TION history AGE M E C H A N I C S psychology Modern India (1857 – 1969) Subject: MODERN INDIA (1857 – 1969) Credits: 4 SYLLABUS Historical background – British rule and its legacies, National movement, Partition and Independence Origins and goals of the Indian National Congress, Formation of the Muslim League Roles played by Gandhi, Nehru, Jinnah and the British in the development of the Movement for independence Challenges faced by the Government of India, Making the Constitution, Political, Economic and Social developments from 1950-1990, The Nehru Years – challenges of modernization and diversity, Brief on Indira Gandhi Developments post-1990, Economic liberalization, Rise of sectarianism and caste based politics, Challenges to internal security Foreign Policy: post – Nehru years, Pakistan and Kashmir, Nuclear policy, China and the U. S. Suggested Readings: 1. Ramachandra Guha, Makers of Modern India, Belknap Press 2. Akash Kapur, India Becoming: A Portrait of Life in Modern India, Riverhead Hardcover 3. Bipin Chandra, History Of Modern India, Orient Blackswan 4. Barbara D. Metcalf, Thomas R. Metcalf, A Concise History of Modern India, Cambridge University Press CHAPTER 1 IMPERIALISM, COLONIALISM AND NATIONALISM STRUCTURE Learning objectives Imperialism and colonialism: A theoretical perspective Imperialism: Its effects The rise of national consciousness The revolt of 1857 Colonialism: -

Calcutta & West Bengal, 1950S

People, Politics and Protests I Calcutta & West Bengal, 1950s – 1960s Sucharita Sengupta & Paula Banerjee Anwesha Sengupta 2016 1. Refugee Movement: Another Aspect of Popular Movements in West Bengal in the 1950s and 1960s Sucharita Sengupta & Paula Banerjee 1 2. Tram Movement and Teachers’ Movement in Calcutta: 1953-1954 Anwesha Sengupta 25 Refugee Movement: Another Aspect of Popular Movements in West Bengal in the 1950s and 1960s ∗ Sucharita Sengupta & Paula Banerjee Introduction By now it is common knowledge how Indian independence was born out of partition that displaced 15 million people. In West Bengal alone 30 lakh refugees entered until 1960. In the 1970s the number of people entering from the east was closer to a few million. Lived experiences of partition refugees came to us in bits and pieces. In the last sixteen years however there is a burgeoning literature on the partition refugees in West Bengal. The literature on refugees followed a familiar terrain and set some patterns that might be interesting to explore. We will endeavour to explain through broad sketches how the narratives evolved. To begin with we were given the literature of victimhood in which the refugees were portrayed only as victims. It cannot be denied that in large parts these refugees were victims but by fixing their identities as victims these authors lost much of the richness of refugee experience because even as victims the refugee identity was never fixed as these refugees, even in the worst of times, constantly tried to negotiate with powers that be and strengthen their own agency. But by fixing their identities as victims and not problematising that victimhood the refugees were for a long time displaced from the centre stage of their own experiences and made “marginal” to their narratives. -

Journal of Literature, Linguistics and Cultural Studies

RAINBOW Vol. 9 (2) 2020 Journal of Literature, Linguistics and Cultural Studies https://journal.unnes.ac.id/sju/index.php/rainbow Pre-partition India and the Rise of Indian Nationalism in Amitav Ghosh’s The Shadow Lines: A Postcolonial Analysis Sheikh Zobaer* * Lecturer, Department of English and Modern Languages, North South University, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Article Info Abstract Article History: The Shadow Lines is mostly celebrated for capturing the agony and trauma of the artificial Received segregation that divided the Indian subcontinent in 1947. However, the novel also 17 August 2020 provides a great insight into the undivided Indian subcontinent during the British colonial Approved period. Moreover, the novel aptly captures the rise of Indian nationalism and the struggle 13 October 2020 against the British colonial rule through the revolutionary movements. Such image of pre- Published partition India is extremely important because the picture of an undivided India is what 30 October 2020 we need in order to compare the scenario of pre-partition India with that of a postcolonial India divided into two countries, and later into three with the independence of Keywords: Partition, Bangladesh in 1971. This paper explores how The Shadow Lines captures colonial India Nationalism, and the rise of Indian nationalism through the lens of postcolonialism.s. Colonialism, Amitav Ghosh © 2020 Universitas Negeri Semarang Corresponding author: Bashundhara, Dhaka-1229, Bangladesh E-mail: [email protected] but cannot separate the people who share the INTRODUCTION same history and legacy of sharing the same territory and living the same kind of life for The Shadow Lines is arguably the most centuries.