Permanent Spring Dilip Simeon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contribution of Bengal in Freedom Struggle by CDT Nikita Maity Reg No

Contribution of Bengal in freedom struggle By CDT Nikita Maity Reg No: WB19SWN136584 No 1 Bengal Naval NCC Unit Kol-C, WB&Sikkim Directorate Freedom is something which given to every organism who has born on this Earth. It is that right which is given to everyone irrespective of anything. India (Bharat) was one of prosperous country of the world and people from different parts of world had come to rule over her, want to take her culture and heritage but she had always been brave and protected herself from various invaders. The last and the worst invader was British East India Company. BEIC not only drained India‟s wealth but also had destroyed our rich culture and knowledge. They had tried to completely destroy India in every aspect. But we Indian were not going to let them be successful in their dirty plan. Every section of Indian society had revolved in their own way. One of the major and consistent revolved was going in then Bengal province. In Bengal, from writer to fighter and from men to women everyone had given everything for freedom. One of the prominent forefront freedom fighter was Netaji Shubhas Chandra Bose. Netaji was born on 23rd January, 1897 in Cuttack. He had studied in Presidency College. In 1920 he passed the civil service examination, but in April 1921, after hearing of the nationalist turmoil in India, he resigned his candidacy and hurried back to India. He started the newspaper 'Swaraj'. He was founder of Indian National Army(INA) or Azad Hind Fauj. There was also an all-women regiment named after Rani of Jhanshi, Lakshmibai. -

Women on Fire: Sati, Consent, and the Revolutionary Subject

,%-.%/& 0121 Women on Fire: Immolation, Consent, and the Revolutionary Subject Sisters-in-Arms On September 23, 1932, Pritilata Waddedar, a twenty-year-old schoolteacher and member of the Indian Republican Army (&31),¹ became the first woman to die in the commission of an anticolonial attack when she committed suicide after leading a raid on the Pahartali Railway Institute in Chittagong. Police found Waddedar’s body outside the club, dressed in men’s clothes and with no visible injuries, and discovered, tucked into her shirt, several pamphlets of her own writing, including “Long Live Revolution” and “An Appeal to Women.” In the latter, she had written, “Women to day have taken the firm resolution that they will not remain in the background. For the freedom of their motherland they are willing to stand side by side with their brothers in every action however hard or fearful it may be. To offer proof I have taken upon myself the leadership of this expedition to be launched today” (122).² Her body, spectacularly still outside the site of her attack, offers proof of another order. Of what it offers proof, the modes of reading and memorialization it invites, and the afterlives of that body and its articu- lations constitute the terms of a colonial and postcolonial struggle over Volume 24, Number 3 $%& 10.1215/10407391-2391959 © 2014 by Brown University and differences : A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 64 Women on Fire meaning making. At the time, Waddedar’s dead body took on a kind of evidentiary status in the prosecution of her comrades, a colonial assertion of authority in the courtroom—a prophecy, perhaps, of the ways in which it would come again to be, decades later, the disputed object of historical narrative. -

Contributions of Lala Har Dayal As an Intellectual and Revolutionary

CONTRIBUTIONS OF LALA HAR DAYAL AS AN INTELLECTUAL AND REVOLUTIONARY ABSTRACT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF ^ntiat ai pijtl000pi{g IN }^ ^ HISTORY By MATT GAOR CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2007 ,,» '*^d<*'/. ' ABSTRACT India owes to Lala Har Dayal a great debt of gratitude. What he did intotality to his mother country is yet to be acknowledged properly. The paradox ridden Har Dayal - a moody idealist, intellectual, who felt an almost mystical empathy with the masses in India and America. He kept the National Independence flame burning not only in India but outside too. In 1905 he went to England for Academic pursuits. But after few years he had leave England for his revolutionary activities. He stayed in America and other European countries for 25 years and finally returned to England where he wrote three books. Har Dayal's stature was so great that its very difficult to put him under one mould. He was visionary who all through his life devoted to Boddhi sattava doctrine, rational interpretation of religions and sharing his erudite knowledge for the development of self culture. The proposed thesis seeks to examine the purpose of his returning to intellectual pursuits in England. Simultaneously the thesis also analyses the contemporary relevance of his works which had a common thread of humanism, rationalism and scientific temper. Relevance for his ideas is still alive as it was 50 years ago. He was true a patriotic who dreamed independence for his country. He was pioneer for developing science in laymen and scientific temper among youths. -

Nationalism in India Lesson

DC-1 SEM-2 Paper: Nationalism in India Lesson: Beginning of constitutionalism in India Lesson Developer: Anushka Singh Research scholar, Political Science, University of Delhi 1 Institute of Lifelog learning, University of Delhi Content: Introducing the chapter What is the idea of constitutionalism A brief history of the idea in the West and its introduction in the colony The early nationalists and Indian Councils Act of 1861 and 1892 More promises and fewer deliveries: Government of India Acts, 1909 and 1919 Post 1919 developments and India’s first attempt at constitution writing Government of India Act 1935 and the building blocks to a future constitution The road leading to the transfer of power The theory of constitutionalism at work Conclusion 2 Institute of Lifelog learning, University of Delhi Introduction: The idea of constitutionalism is part of the basic idea of liberalism based on the notion of individual’s right to liberty. Along with other liberal notions,constitutionalism also travelled to India through British colonialism. However, on the one hand, the ideology of liberalism guaranteed the liberal rightsbut one the other hand it denied the same basic right to the colony. The justification to why an advanced liberal nation like England must colonize the ‘not yet’ liberal nation like India was also found within the ideology of liberalism itself. The rationale was that British colonialism in India was like a ‘civilization mission’ to train the colony how to tread the path of liberty.1 However, soon the English educated Indian intellectual class realised the gap between the claim that British Rule made and the oppressive and exploitative reality of colonialism.Consequently,there started the movement towards autonomy and self-governance by Indians. -

History, Amnesia and Public Memory the Chittagong Armoury Raid, 1930-34

History, Amnesia and Public Memory The Chittagong Armoury Raid, 1930-34 Sachidananda Mohanty In this essay, I reconstruct the main It is impossible to think of the 1905.The chief architect of this phase outline of the Chittagong Armoury Chittagong movement without the was Sri Aurobindo, then known as Raid and the uprising against the intellectual, political and martial Aurobindo Ghosh. His maternal British at Chittagong (former East leadership of Surjya Sen. During his grandfather, Rajnarayan Bose, had Bengal, now Bangladesh) between college days, he came under the in 1876 formed a secret society called 1930 and 34. I also explore the reasons influence of the national movement Sanjibani Sabha of which several that might help explain the erasure of and vowed to dedicate his life to members of the Tagore family were this significant episode from public national liberation. According to other members. In a series of articles in memory in India as well as accounts, Surjya Sen, Ambika Induprakash, a weekly from Bombay Bangladesh. I rely, in the main, on Chakraborty and others were initiated edited by KG Deshpande, Sri available historical evidence including into the movement by Hemendra Aurobindo severely criticised the Manini Chatterjee’s well documented Mukhoti, an absconder in the Barisal Congress policies for sticking to non- volume Do and Die: The Chittagong Conspiracy Case. violence. He sent a Bengali soldier of Uprising 1930 and 34 (Penguin The Chittagong group’s early the Baroda army, named Jatin Books, India, 1999). I supplement this inspiration came from the Bengal Banerjee to Bengal with the objective with information based on a recent visit revolutionaries who came into of establishing a secret group to to Bangladesh and my conversations prominence especially during the undertake revolutionary propaganda Partition of Bengal Movement in and recruitment. -

BA III, Paper VI, Anuradha Jaiswal Phase 1 1) Anusilan S

Revolutionaries In India (Indian National Movement) (Important Points) B.A III, Paper VI, Anuradha Jaiswal Phase 1 1) Anusilan Samiti • It was the first revolutionary organisation of Bengal. • Second Branch at Baroda. • Their leader was Rabindra Kumar Ghosh • Another important leader was P.Mitra who was the actual leader of the group. • In 1908, the samiti published a book called Bhawani Mandir. • In 1909 they published Vartaman Ranniti. • They also published a book called Mukti Kon Pathe (which way lie salvation) • Barindra Ghosh tried to explore a bomb in Maniktala in Calcutta. • Members – a) Gurudas Banerjee. b) B.C.Pal • Both of them believed in the cult of Durga. • Aurobindo Ghosh started Anushilan Samiti in Baroda. • He sent Jatindra Nath Banerjee to Calcutta and his association merged with Anusilan Samiti in Calcutta. 2) Prafull Chaki and Khudi Ram Bose • They tried to kill Kings Ford, Chief Presidency Magistrate, who was a judge at Muzaffarpur in Bihar but Mrs Kennedy and her daughter were killed instead in the blast. • Prafulla Chaki was arrested but he shot himself dead and Khudiram was hanged. This bomb blast occurred on 30TH April 1908. 3) Aurobindo Ghosh and Barindra Ghosh • They were arrested on May 2, 1908. • Barindra was sentenced for life imprisonment (Kalapani) and Aurobindo Ghosh was acquitted. • This conspiracy was called Alipore conspiracy. • The conspiracy was leaked by the authorities by Narendra Gosain who was killed by Kanhiya Lal Dutta and Satyen Bose within the jail compound. 4. Lala Hardayal, Ajit Singhand &Sufi Amba Prasad formed a group at Saharanpur in 1904. 5. -

Conspiracy Rises Again Racial Sympathy and Radical Solidarity Across Empires

Conspiracy Rises Again Racial Sympathy and Radical Solidarity across Empires poulomi saha When in 1925 members of the Jugantar, a secret revolutionary asso- ciation in colonial India, began to conceive of what they believed to be a more effective strategy of anticolonial revolt than that of non- violence promoted at the time by the mainstream Congress Party in Chittagong, they chose for themselves a new name: the Indian Re- publican Army (IRA). In so doing, they explicitly constructed a rev- olutionary genealogy from which their future actions were to draw inspiration, a direct link between the anticolonial revolt in East Ben- gal and the 1916 Easter Uprising in Ireland.1 The 1930 attack on the Chittagong Armory, the first in a series of revolutionary actions tak- en by the IRA, also marked the anniversary of the Irish rebellion. The very language of Irish revolt seeped into the practices of the Indian organization as they smuggled in illegal copies of the writings of Dan Breen and Éamon de Valera and began each meeting with a reading of the Proclamation of the Irish Provisional Government. The ideological and textual kinship between these two anticolo- nial communities and another former holding of the British empire, the United States, illuminates transcolonial circuits that formed a qui parle Vol. 28, No. 2, December 2019 doi 10.1215/10418385-7861837 © 2019 Editorial Board, Qui Parle Downloaded from https://read.dukeupress.edu/qui-parle/article-pdf/28/2/307/740477/307saha.pdf by UNIV CA BERKELEY PERIODICALS user on 05 February 2020 308 qui parle december 2019 vol. -

Swap an Das' Gupta Local Politics

SWAP AN DAS' GUPTA LOCAL POLITICS IN BENGAL; MIDNAPUR DISTRICT 1907-1934 Theses submitted in fulfillment of the Doctor of Philosophy degree, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 1980, ProQuest Number: 11015890 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11015890 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis studies the development and social character of Indian nationalism in the Midnapur district of Bengal* It begins by showing the Government of Bengal in 1907 in a deepening political crisis. The structural imbalances caused by the policy of active intervention in the localities could not be offset by the ’paternalistic* and personalised district administration. In Midnapur, the situation was compounded by the inability of government to secure its traditional political base based on zamindars. Real power in the countryside lay in the hands of petty landlords and intermediaries who consolidated their hold in the economic environment of growing commercialisation in agriculture. This was reinforced by a caste movement of the Mahishyas which injected the district with its own version of 'peasant-pride'. -

Khudiram Bose the Symbol of Valiance and Death Defying Youth

Khudiram Bose The Symbol of Valiance and Death Defying Youth The silent night was approaching dawn. Footsteps of the guards in the jail corridor broke the silence. Slowly it stopped before the ‘condemned cell’. When the get was opened, a teenage boy with a smiling innocent face greeted them. He advanced in fearless strides to embrace death, with the guards merely following him. He stood upright on the execution platform, with the smile unfaded. His face was covered with green cloth, hands were tied behind, the rope encircled his neck. The boy stood unflinched. With the signal of the jailor Mr. Woodman, hangman pulled the lever. The rope swinging a little became still. It was 6 am. The day was 11th August 1908. The martyrdom of death defying Khudiram demarcated the onset of a new era in the course of Indian freedom movement. The martyrdom of Khudiram rocked the entire nation. The dormant youth of a subject nation, oblivious of its own strength, dignity and valor shook off its hibernation. Khudiram’s martyrom brought a new meaning of life, new concept of dignity to the youth of his day. In his wake, like wave after wave, hundreds and thousands of martyrs upheld the truth that the only way to lead a dignified life is by dedicating it for the noblest cause, freedom. They came one after another, incessantly, shed their bloods, faced terrible torture, but never bowed their heads down. 3rd December 1889. Khudiram was born at Habibpur village, adjacent to Midnapore town. His father was Troilokyanath and his mother was Laksmipriya Devi. -

Independence Day

INDEPENDENCE DAY ‘Swaraj is my Birthright and I shall have it’- Bal Gangadhar Tilak India celebrates its Independence Day on 15th August every year. Independence Day reminds us of all the sacrifices that were made by our freedom fighters to make India free from British rule. On 15th August 1947, India was declared independent from British colonialism and became the largest democracy in the world. "Tryst with Destiny" was an English-language speech delivered by Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of India, to the Indian Constituent Assembly in the Parliament, on the eve of India's Independence, towards midnight on 14 August 1947. The speech spoke on the aspects that transcended Indian history. It is considered to be one of the greatest speeches of the 20th century and to be a landmark oration that captures the essence of the triumphant culmination of the Indian independence movement against British colonial rule in India. The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events with the ultimate aim of ending British rule in India. The movement spanned from 1857 to 1947. The first nationalistic revolutionary movement for Indian independence emerged from Bengal. It later took root in the newly formed Indian National Congress with prominent moderate leaders seeking only their fundamental right to appear for Indian Civil Service examinations in British India, as well as more rights (economical in nature) for the people of the soil. The early part of the 20th century saw a more radical approach towards political self-rule proposed by leaders such as the Lal Bal Pal triumvirate, Aurobindo Ghosh and V. -

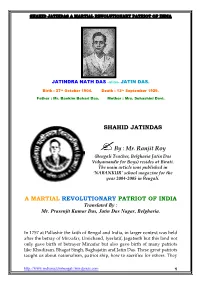

JATINDRA NATH DAS -Alias- JATIN DAS

JATINDRA NATH DAS -alias- JATIN DAS. Birth : 27 th October 1904. Death : 13 th September 1929. Father : Mr. Bankim Behari Das. Mother : Mrs. Suhashini Devi. SHAHID JATINDAS ?By : Mr. Ranjit Roy (Bengali Teacher, Belgharia Jatin Das Vidyamandir for Boys) resides at Birati. The main article was published in ‘NABANKUR’ school magazine for the year 2004-2005 in Bengali. A MARTIAL REVOLUTIONARY PATRIOT OF INDIA Translated By : Mr. Prasenjit Kumar Das, Jatin Das Nagar, Belgharia. In 1757 at Pallashir the faith of Bengal and India, in larger context was held after the betray of Mirzafar, Umichand, Iyerlatif, Jagatseth but this land not only gave birth of betrayer Mirzafar but also gave birth of many patriots like Khudiram, Bhagat Singh, Baghajatin and Jatin Das. These great patriots taught us about nationalism, patriot ship, how to sacrifice for others. They http://www.indianactsinbengali.wordpress.com 1 have tried their best to uphold the head of a unified, independent and united nation. Let us discuss about one of them, Jatin Das and his great sacrifice towards the nation. on 27 th October 1904 Jatin Das (alias Jatindra Nath Das) came to free the nation from the bondage of the British Rulers. He born at his Mother’s house at Sikdar Bagan. He was the first child of father Bankim Behari Das and mother Suhashini Devi. After birth the newborn did not cried for some time then the child cried loudly, it seems that the little one was busy in enchanting the speeches of motherland but when he saw that his motherland is crying for her bondage the little one cant stop crying. -

Oneway Regulation

ONEWAY REGULATION Guard Name Road Name Road New Oneway Oneway Direction Time Remarks Name Stretch Stretch1 BHAWANIPORE Baker Road Biplabi Kanai Entire Entire N-S 08.00- TRAFFIC GUARD Bhattacharya Sarani 20.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Chakraberia Pandit Modan From Sarat Bose From Sarat E-W 08.00- TRAFFIC GUARD Road (North) Mohan Malaviya Rd to B/ Circular Bose Rd to B/ 14.00hrs Sarani Rd Circular Rd BHAWANIPORE Elgin Road Lala Lajpat Rai Entire Entire W-E 14.00- TRAFFIC GUARD Sarani 20.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Harish Mukherjee Entire Entire N-S 14.00- TRAFFIC GUARD Road 21.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Harish Mukherjee Entire Entire S-N 08.00- TRAFFIC GUARD Road 14.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Hasting Park Entire Entire S-N 08.00- Except Sunday TRAFFIC GUARD Road 20.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Justice Ch Entire Entire E-W 14.00- TRAFFIC GUARD Madhab Road 20.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Justice Ch Entire Entire W-E 08.00- TRAFFIC GUARD Madhab Road 14.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Kali Temple Road Entire Entire E-W 08.00- TRAFFIC GUARD 14.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Kalighat Rd Manya Sardar B K Hazra Rd to Hazra Rd to N-S 08.00- TRAFFIC GUARD (portion) Maitra Road Harish Mukherjee Harish 14.00hrs Rd Mukherjee Rd BHAWANIPORE Kalighat Rd Manya Sardar B K Hazra Rd to Hazra Rd to S-N 14.00- TRAFFIC GUARD (portion) Maitra Road Harish Mukherjee Harish 21.00hrs Rd Mukherjee Rd BHAWANIPORE Lee Road O C Ganguly Sarani Entire Entire N-S 08.00- TRAFFIC GUARD 14.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Lee Road O C Ganguly Sarani Entire Entire S-N 14.00- TRAFFIC GUARD 21.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Motilal Nehru N-S 14.00- TRAFFIC GUARD Road 21.00hrs BHAWANIPORE