The Foundation and Early Years of the News of the World: 'Capacious Double Sheets'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social and Cultural Functions of the Local Press in Preston, Lancashire, 1855-1900

Reading the local paper: Social and cultural functions of the local press in Preston, Lancashire, 1855-1900 by Andrew Hobbs A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire November 2010 ABSTRACT This thesis demonstrates that the most popular periodical genre of the second half of the nineteenth century was the provincial newspaper. Using evidence from news rooms, libraries, the trade press and oral history, it argues that the majority of readers (particularly working-class readers) preferred the local press, because of its faster delivery of news, and because of its local and localised content. Building on the work of Law and Potter, the thesis treats the provincial press as a national network and a national system, a structure which enabled it to offer a more effective news distribution service than metropolitan papers. Taking the town of Preston, Lancashire, as a case study, this thesis provides some background to the most popular local publications of the period, and uses the diaries of Preston journalist Anthony Hewitson as a case study of the career of a local reporter, editor and proprietor. Three examples of how the local press consciously promoted local identity are discussed: Hewitson’s remoulding of the Preston Chronicle, the same paper’s changing treatment of Lancashire dialect, and coverage of professional football. These case studies demonstrate some of the local press content that could not practically be provided by metropolitan publications. The ‘reading world’ of this provincial town is reconstructed, to reveal the historical circumstances in which newspapers and the local paper in particular were read. -

The Technology, Media and Telecommunications Review

The Technology, Media and Telecommunications Review Third Edition Editor John P Janka Law Business Research The Technology, Media and Telecommunications Review THIRD EDITION Reproduced with permission from Law Business Research Ltd. This article was first published in TheT echnology, Media and Telecommunications Review, 3rd edition (published in October 2012 – editor John P Janka). For further information please email [email protected] 2 The Technology, Media and Telecommunications Review THIRD EDITION Editor John P Janka Law Business Research Ltd The Law Reviews THE MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS REVIEW THE RESTRUCTURING REVIEW THE PRIVATE COMPETITION ENFORCEMENT REVIEW THE DISPUTE RESOLUTION REVIEW THE EMPLOYMENT LAW REVIEW THE PUBLIC COMPETITION ENFORCEMENT REVIEW THE BANKING REGULATION REVIEW THE INTERNATIONAL ARBITRATION REVIEW THE MERGER CONTROL REVIEW THE TECHNOLOGY, MEDIA AND TELECOMMUNICATIONS REVIEW THE INWARD INVESTMENT AND INTERNATIONAL TAXATION REVIEW THE CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REVIEW THE CORPORATE IMMIGRATION REVIEW THE INTERNATIONAL INVESTIGATIONS REVIEW THE PROJECTS AND CONSTRUCTION REVIEW THE INTERNATIONAL CAPITAL MARKETS REVIEW THE REAL ESTATE LAW REVIEW THE PRIVATE EQUITY REVIEW THE ENERGY REGULATION AND MARKETS REVIEW THE INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY REVIEW THE ASSET MANAGEMENT REVIEW THE PRIVATE WEALTH AND PRIVATE CLIENT REVIEW www.TheLawReviews.co.uk PUBLISHER Gideon Roberton BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT MANAGER Adam Sargent MARKETING MANAGERS Nick Barette, Katherine Jablonowska, Alexandra Wan PUBLISHING ASSISTANT Lucy Brewer EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Lydia Gerges PRODUCTION MANAGER Adam Myers PRODUCTION EDITOR Joanne Morley SUBEDITOR Caroline Rawson EDITor-in-CHIEF Callum Campbell MANAGING DIRECTOR Richard Davey Published in the United Kingdom by Law Business Research Ltd, London 87 Lancaster Road, London, W11 1QQ, UK © 2012 Law Business Research Ltd © Copyright in individual chapters vests with the contributors No photocopying: copyright licences do not apply. -

![[.Watch.] News of the World (2020) Movie Online Full 11 June 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7290/watch-news-of-the-world-2020-movie-online-full-11-june-2021-187290.webp)

[.Watch.] News of the World (2020) Movie Online Full 11 June 2021

[.Watch.] News of the World (2020) Movie Online Full 11 June 2021 11 secs ago. mAniAc.mAyhEm.XSTRETCHY/Watch News of the World (2021) Full Movie Online Free HD,News of the World Full Free, [#NewsoftheWorld2021] Full Movie Online, Watch News of the World Movie Online Free,News of the World Movie Full Watch Online Free Official STRETCHY Business Partner with watching NEWS OF THE WORLD Online (2021) Full ARCTIC/DESTRETCHY!!~watch News of the World (2021) FULL Movie Online Free? HQ Reddit&Youtube Video [STRETCHY] News of the World (2021) Full Movie Watch online free [#NewsoftheWorld2021] Google Drive/News of the World (2021) Full Movie Watch online No Sign Up English 123Movies #NewsoftheWorld2021 Online !! In News of the World, the gang is back but the game has changed. As they return to rescue one of their own, the players will have to brave parts unknown from arid deserts to snowy mountains, to escape the world’s most dangerous game. News of the World (2021) [STRETCHY] | Watch News of the World Online 2021 Full Movie Free HD.720Px|Watch News of the World Online 2021 Full MovieS Free HD !! News of the World (2021) with English Subtitles ready for download, News of the World 2021 720p, 1080p, BrRip, DvdRip, Youtube, Reddit, Multilanguage and High Quality. Watch News of the World Online Free Streaming, Watch News of the World Online Full Streaming In HD Quality, Let’s go to watch the latest movies of your favorite movies, News of the World. come on join us!! What happened in this movie? I have a summary for you. -

A History of the British Sporting Journalist, C.1850-1939

A History of the British Sporting Journalist, c.1850-1939 A History of the British Sporting Journalist, c.1850-1939: James Catton, Sports Reporter By Stephen Tate A History of the British Sporting Journalist, c.1850-1939: James Catton, Sports Reporter By Stephen Tate This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Stephen Tate All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-4487-7 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-4487-1 To the memory of my parents Kathleen and Arthur Tate CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................... x Introduction ............................................................................................... xi Chapter One ................................................................................................ 1 Stadium Mayhem Chapter Two ............................................................................................. 15 Unlawful and Disgraceful Gatherings Chapter Three ........................................................................................... 33 A Well-Educated Youth as Apprentice to Newspaper -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

History and Bibliography of American Newspapers 1690-1820

Additions and Corrections to History and Bibliography of American Newspapers 1690-1820 BY CLARENCE S. BRIGHAM FOREWORD HESE additions and corrections cover only certain T fields of the parent work which was published in 1947 in two volumes. All new titles are carefully entered and described, although only nine such titles have been dis- covered in the last thirteen years. Only unique issues acquired by libraries have been entered. Certain libraries, like the Library of Congress, the New York libraries, and especially the American Antiquarian Society, have acquired thousands of issues in the past few years, but these are all in long or complete files and generally are not mentioned. Libraries which have sent me lists of issues recently obtained should note this fact and not expect to find all copies listed. In a few cases long files acquired by libraries have been entered, on the assumption that they might contain a few issues not in the supposedly complete files in other libraries. New biographical facts concerning publishers, printers, and editors are entered. Frequently, the complete spellings of Christian names hitherto known only by initials are given. Important changes in the historical accounts of newspapers i6 AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY [April, have been entered. Most of these changes have been ob- tained through correspondence, or by noting the record of additions in printed reports or bulletins of libraries. There has been no attempt to visit the many libraries to re-examine the various files. Microfilm reproductions issued by various libraries in the past few years have been noted, although not the many libraries purchasing such microfilm files. -

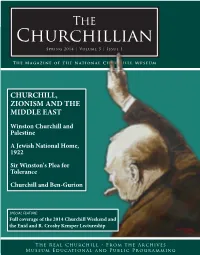

Spring 2014 | Volume 5 | Issue 1

The Churchillian Spring 2014 | Volume 5 | Issue 1 The Magazine of the National Churchill Museum CHURCHILL, ZIONISM AND THE MIDDLE EAST Winston Churchill and Palestine A Jewish National Home, 1922 Sir Winston's Plea for Tolerance Churchill and Ben-Gurion SPECIAL FEATURE: Full coverage of the 2014 Churchill Weekend and the Enid and R. Crosby Kemper Lectureship The Real Churchill • From the Archives Museum Educational and Public Programming Board of Governors of the Association of Churchill Fellows FROM THE Jean-Paul Montupet MESSAGE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Chairman & Senior Fellow St. Louis, Missouri A.V. L. Brokaw, III Warm greetings from the campus of St. Louis, Missouri Westminster College. As I write, we are Robert L. DeFer still recovering from a wonderful Churchill th Weekend. Tis weekend, marking the 68 Earle H. Harbison, Jr. St. Louis, Missouri anniversary of Churchill’s visit here and his William C. Ives Sinews of Peace address, was a special one for Chapel Hill, North Carolina several reasons. Firstly, because of the threat R. Crosby Kemper, III of bad weather which, while unpleasant, Kansas City, Missouri never realized the forecast’s dismal potential Barbara D. Lewington and because of the presence of members of St. Louis, Missouri the Churchill family, Randolph, Catherine St. Louis, Missouri and Jennie Churchill for a frst ever visit. William R. Piper Tis, in tandem with a wonderful Enid St. Louis, Missouri PHOTO BY DAK DILLON and R. Crosby Kemper Lecture delivered by Paul Reid, defed the weather and entertained a bumper crowd of St. Louis, Missouri Churchillians at both dinner, in the Museum, and at a special ‘ask the experts’ brunch. -

Press Freedom Under Attack

LEVESON’S ILLIBERAL LEGACY AUTHORS HELEN ANTHONY MIKE HARRIS BREAKING SASHY NATHAN PADRAIG REIDY NEWS FOREWORD BY PROFESSOR TIM LUCKHURST PRESS FREEDOM UNDER ATTACK , LEVESON S ILLIBERAL LEGACY FOREWORD EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. WHY IS THE FREE PRESS IMPORTANT? 2. THE LEVESON INQUIRY, REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS 2.1 A background to Leveson: previous inquiries and press complaints bodies 2.2 The Leveson Inquiry’s Limits • Skewed analysis • Participatory blind spots 2.3 Arbitration 2.4 Exemplary Damages 2.5 Police whistleblowers and press contact 2.6 Data Protection 2.7 Online Press 2.8 Public Interest 3. THE LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK – A LEGAL ANALYSIS 3.1 A rushed and unconstitutional regime 3.2 The use of statute to regulate the press 3.3 The Royal Charter and the Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Act 2013 • The use of a Royal Charter • Reporting to Parliament • Arbitration • Apologies • Fines 3.4 The Crime and Courts Act 2013 • Freedom of expression • ‘Provided for by law’ • ‘Outrageous’ • ‘Relevant publisher’ • Exemplary damages and proportionality • Punitive costs and the chilling effect • Right to a fair trial • Right to not be discriminated against 3.5 The Press Recognition Panel 4. THE WIDER IMPACT 4.1 Self-regulation: the international norm 4.2 International response 4.3 The international impact on press freedom 5. RECOMMENDATIONS 6. CONCLUSION 3 , LEVESON S ILLIBERAL LEGACY 4 , LEVESON S ILLIBERAL LEGACY FOREWORD BY TIM LUCKHURST PRESS FREEDOM: RESTORING BRITAIN’S REPUTATION n January 2014 I felt honour bound to participate in a meeting, the very ‘Our liberty cannot existence of which left me saddened be guarded but by the and ashamed. -

Imperial Japanese Propaganda and the Founding of the Japan Times 1897-1904

Volume 19 | Issue 12 | Number 2 | Article ID 5604 | Jun 15, 2021 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Imperial Japanese Propaganda and the Founding of The Japan Times 1897-1904 Alexander Rotard Abstract: Founded in 1897 as a semi-official government organ by Zumoto Motosada with the support of Itō Hirobumi and Fukuzawa Yukichi, The Japan Times played an essential role, as the first English-language newspaper to be edited by Japanese, in shaping Western understandings of Japan and Japanese modernisation in the late 19th to early 20th centuries. The Japan Times framed Japanese ‘modernisation’ in the language of Western civilisation, thus facilitating Japan’s rapprochement with the Western Powers (particularly with Great Britain) in the late 19th century by presenting Japan as a ‘civilised’ (i.e., Western) nation-state. The paper played an equally important role in manipulating Western public discourses in favour of Japan’s expansionist ambitions in Asia by framing justifications for Japanese foreign policy in concepts of Western civilisation. Keywords: Meiji-era Japanese propaganda, Zumoto Motosada, founder of The Japan Times1 The Japan Times, Zumoto Motosada, Japanese Imperialism, Anglo-Japanese rapprochement, colonisation of Korea. Introduction . Despite The Japan Times’ critical role as a Japanese Government propaganda organ, the paper has been greatly understudied in both the Japanese and English literature. Japanese- language studies of The Japan Times and Zumoto Motosada exist in small number2 but thorough research into The Japan Times’ role as a promoter of Meiji Government propaganda 1 19 | 12 | 2 APJ | JF has yet to be undertaken in English orthe Korean press has been well examined by Japanese. -

Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University In

79I /f NIGERIAN MILITARY GOVERNMENT AND PRESS FREEDOM, 1966-79 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Ehikioya Agboaye, B.A. Denton, Texas May, 1984 Agboaye, Ehikioya, Nigerian Military Government and Press Freedom, 1966-79. Master of Arts (Journalism), May, 1984, 3 tables, 111 pp., bibliography, 148 titles. The problem of this thesis is to examine the military- press relationship inNigeria from 1966 to 1979 and to determine whether activities of the military government contributed to violation of press freedom by prior restraint, postpublication censorship and penalization. Newspaper and magazine articles related to this study were analyzed. Interviews with some journalists and mili- tary personnel were also conducted. Materials collected show that the military violated some aspects of press freedom, but in most cases, however, journalists were free to criticize government activities. The judiciary prevented the military from arbitrarily using its power against the press. The findings show that although the military occasionally attempted suppressing the press, there are few instances that prove that journalists were denied press freedom. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES............ .P Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 1 Statement of the Problem Purpose of the Study Significant Questions Definition of Terms Review of the Literature Significance of the Study Limitations Methodology Organization II. PREMILITARY ERA,.... 1865-1966...18 . From Colonial to Indigenous Press The Press in the First Republic III. PRESS ACTIONS IN THE MILITARY'S EARLY YEARS 29 Before the Civil War The Nigeria-Biaf ran War and After IV. -

The Experiences of Mississippi Weekly Newspaper Editors As They

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Fall 12-2010 The Experiences of Mississippi Weekly Newspaper Editors as They Explore and Consider Producing Internet Editions Cassandra Denise Johnson University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Cassandra Denise, "The Experiences of Mississippi Weekly Newspaper Editors as They Explore and Consider Producing Internet Editions" (2010). Dissertations. 528. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/528 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi THE EXPERIENCES OF MISSISSIPPI WEEKLY NEWSPAPER EDITORS AS THEY EXPLORE AND CONSIDER PRODUCING INTERNET EDITIONS by Cassandra Denise Johnson Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2010 ABSTRACT THE EXPERIENCES OF MISSISSIPPI WEEKLY NEWSPAPER EDITORS AS THEY EXPLORE AND CONSIDER PRODUCING INTERNET EDITIONS by Cassandra Denise Johnson December 2010 This dissertation focused on the challenges Mississippi weekly newspaper editors faced when deciding to have an online edition and the issues these editors encountered when they adopted a Web newspaper. The study expounded on four areas – the operational changes weekly newspapers have had to make to produce Web editions, the different type of newsroom staff that are needed to create both editions, the content that is going in the online edition, and the financial pressures that editors work through to keep the newspapers profitable. -

The Electric Telegraph

To Mark, Karen and Paul CONTENTS page ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENTS TO 1837 13 Early experiments—Francis Ronalds—Cooke and Wheatstone—successful experiment on the London & Birmingham Railway 2 `THE CORDS THAT HUNG TAWELL' 29 Use on the Great Western and Blackwall railways—the Tawell murder—incorporation of the Electric Tele- graph Company—end of the pioneering stage 3 DEVELOPMENT UNDER THE COMPANIES 46 Early difficulties—rivalry between the Electric and the Magnetic—the telegraph in London—the overhouse system—private telegraphs and the press 4 AN ANALYSIS OF THE TELEGRAPH INDUSTRY TO 1868 73 The inland network—sources of capital—the railway interest—analysis of shareholdings—instruments- working expenses—employment of women—risks of submarine telegraphy—investment rating 5 ACHIEVEMENT IN SUBMARINE TELEGRAPHY I o The first cross-Channel links—the Atlantic cable— links with India—submarine cable maintenance com- panies 6 THE CASE FOR PUBLIC ENTERPRISE 119 Background to the nationalisation debate—public attitudes—the Edinburgh Chamber of Commerce— Frank Ives. Scudamore reports—comparison with continental telegraph systems 7 NATIONALISATION 1868 138 Background to the Telegraph Bill 1868—tactics of the 7 8 CONTENTS Page companies—attitudes of the press—the political situa- tion—the Select Committee of 1868—agreement with the companies 8 THE TELEGRAPH ACTS 154 Terms granted to the telegraph and railway companies under the 1868 Act—implications of the 1869 telegraph monopoly 9 THE POST OFFICE TELEGRAPH 176 The period 87o-1914—reorganisation of the