Polygonaceae) in Coastal Central California Christopher P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plant List for Web Page

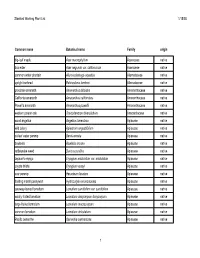

Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 Common name Botanical name Family origin big-leaf maple Acer macrophyllum Aceraceae native box elder Acer negundo var. californicum Aceraceae native common water plantain Alisma plantago-aquatica Alismataceae native upright burhead Echinodorus berteroi Alismataceae native prostrate amaranth Amaranthus blitoides Amaranthaceae native California amaranth Amaranthus californicus Amaranthaceae native Powell's amaranth Amaranthus powellii Amaranthaceae native western poison oak Toxicodendron diversilobum Anacardiaceae native wood angelica Angelica tomentosa Apiaceae native wild celery Apiastrum angustifolium Apiaceae native cutleaf water parsnip Berula erecta Apiaceae native bowlesia Bowlesia incana Apiaceae native rattlesnake weed Daucus pusillus Apiaceae native Jepson's eryngo Eryngium aristulatum var. aristulatum Apiaceae native coyote thistle Eryngium vaseyi Apiaceae native cow parsnip Heracleum lanatum Apiaceae native floating marsh pennywort Hydrocotyle ranunculoides Apiaceae native caraway-leaved lomatium Lomatium caruifolium var. caruifolium Apiaceae native woolly-fruited lomatium Lomatium dasycarpum dasycarpum Apiaceae native large-fruited lomatium Lomatium macrocarpum Apiaceae native common lomatium Lomatium utriculatum Apiaceae native Pacific oenanthe Oenanthe sarmentosa Apiaceae native 1 Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 wood sweet cicely Osmorhiza berteroi Apiaceae native mountain sweet cicely Osmorhiza chilensis Apiaceae native Gairdner's yampah (List 4) Perideridia gairdneri gairdneri Apiaceae -

Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plant List

UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plants Below is the most recently updated plant list for UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve. * non-native taxon ? presence in question Listed Species Information: CNPS Listed - as designated by the California Rare Plant Ranks (formerly known as CNPS Lists). More information at http://www.cnps.org/cnps/rareplants/ranking.php Cal IPC Listed - an inventory that categorizes exotic and invasive plants as High, Moderate, or Limited, reflecting the level of each species' negative ecological impact in California. More information at http://www.cal-ipc.org More information about Federal and State threatened and endangered species listings can be found at https://www.fws.gov/endangered/ (US) and http://www.dfg.ca.gov/wildlife/nongame/ t_e_spp/ (CA). FAMILY NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME LISTED Ferns AZOLLACEAE - Mosquito Fern American water fern, mosquito fern, Family Azolla filiculoides ? Mosquito fern, Pacific mosquitofern DENNSTAEDTIACEAE - Bracken Hairy brackenfern, Western bracken Family Pteridium aquilinum var. pubescens fern DRYOPTERIDACEAE - Shield or California wood fern, Coastal wood wood fern family Dryopteris arguta fern, Shield fern Common horsetail rush, Common horsetail, field horsetail, Field EQUISETACEAE - Horsetail Family Equisetum arvense horsetail Equisetum telmateia ssp. braunii Giant horse tail, Giant horsetail Pentagramma triangularis ssp. PTERIDACEAE - Brake Family triangularis Gold back fern Gymnosperms CUPRESSACEAE - Cypress Family Hesperocyparis macrocarpa Monterey cypress CNPS - 1B.2, Cal IPC -

Low-Effect Habitat Conservation Plan for the Mount Hermon June Beetle

Low-Effect Habitat Conservation Plan for the Mount Hermon June Beetle, the Ben Lomond Wallflower, and the Ben Lomond Spineflower, at Bean Creek Estates, a 13-unit residential development site (APN 022-631-22), Located on Bean Creek Road in Scotts Valley, Santa Cruz County, California Prepared for: Mr. Tom Masters 28225 Robinson Canyon Road Carmel, CA 93923 (831) 625-0413 Prepared by: Richard A. Arnold, Ph.D. Entomological Consulting Services, Ltd. 104 Mountain View Court Pleasant Hill, CA 94523-2188 (925) 825-3784 and Kathy Lyons Biotic Resources Group 2551 So. Rodeo Gulch Road, Suite 12 Soquel, CA 95073-2057 (831) 476-4803 and Todd Graff and Norman Schwartz Bolton Hill Company, Inc. 303 Potrero Street, Suite 42-204 Santa Cruz, CA 95060 (831) 457-8696 Revised Draft March 2007 [Type text] EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Mr. Tom Masters (“Applicant”) has applied for a permit pursuant to section 10 (a)(1)(B) of the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (16 U.S.C. 1531-1544, 87 Stat. 884) (ESA), as amended, from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (the Service) for the incidental take of the endangered Mount Hermon June beetle (Polyphylla barbata). In addition, Mr. Masters is requesting that the Service include the Ben Lomond Wallflower (Erysimum teretifolium), and the Ben Lomond Spineflower (Chorizanthe pungens var. hartwegiana) on the incidental take permit, but that the permit is not being sought for incidental take of these two plant taxa. The potential taking would occur incidental to development of 13 single-family residences at an undeveloped, 18.07-acre parcel (APN 022-631-22) owned by the Applicant and located on Bean Creek Road in Scotts Valley (Santa Cruz, County), CA. -

Northern Coastal Scrub and Coastal Prairie

GRBQ203-2845G-C07[180-207].qxd 12/02/2007 05:01 PM Page 180 Techbooks[PPG-Quark] SEVEN Northern Coastal Scrub and Coastal Prairie LAWRENCE D. FORD AND GREY F. HAYES INTRODUCTION prairies, as shrubs invade grasslands in the absence of graz- ing and fire. Because of the rarity of these habitats, we are NORTHERN COASTAL SCRUB seeing increasing recognition and regulation of them and of Classification and Locations the numerous sensitive species reliant on their resources. Northern Coastal Bluff Scrub In this chapter, we describe historic and current views on California Sagebrush Scrub habitat classification and ecological dynamics of these ecosys- Coyote Brush Scrub tems. As California’s vegetation ecologists shift to a more Other Scrub Types quantitative system of nomenclature, we suggest how the Composition many different associations of dominant species that make up Landscape Dynamics each of these systems relate to older classifications. We also Paleohistoric and Historic Landscapes propose a geographical distribution of northern coastal scrub Modern Landscapes and coastal prairie, and present information about their pale- Fire Ecology ohistoric origins and landscapes. A central concern for describ- Grazers ing and understanding these ecosystems is to inform better Succession stewardship and conservation. And so, we offer some conclu- sions about the current priorities for conservation, informa- COASTAL PRAIRIE tion about restoration, and suggestions for future research. Classification and Locations California Annual Grassland Northern Coastal Scrub California Oatgrass Moist Native Perennial Grassland Classification and Locations Endemics, Near-Endemics, and Species of Concern Conservation and Restoration Issues Among the many California shrub vegetation types, “coastal scrub” is appreciated for its delightful fragrances AREAS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH and intricate blooms that characterize the coastal experi- ence. -

Point Isabel Regional Shoreline Checklist of Wild Plants Sorted Alphabetically by Growth Form, Scientific Name

Point Isabel Regional Shoreline Checklist of Wild Plants Sorted Alphabetically by Growth Form, Scientific Name This is a comprehensive list of the wild plants reported to be found in Point Isabel Regional Shoreline. The plants are sorted alphabetically by growth form, then by sci- entific name. This list includes the common name, family, status, invasiveness rating, origin, longevity, habitat, and bloom dates. EBRPD plant names that have changed since the 1993 Jepson Manual are listed alphabetically in an appendix. Column Heading Description Checklist column for marking off the plants you observe Scientific Name According to The Jepson Manual: Vascular Plants of California, Second Edition (JM2) and eFlora (ucjeps.berkeley.edu/IJM.html) (JM93 if different) If the scientific name used in the 1993 edition of The Jepson Manual (JM93) is different, the change is noted as (JM93: xxx) Common Name According to JM2 and other references (not standardized) Family Scientific family name according to JM2, abbreviated by replacing the “aceae” ending with “-” (ie. Asteraceae = Aster-) Status Special status rating (if any), listed in 3 categories, divided by vertical bars (‘|’): Federal/California (Fed./Calif.) | California Native Plant Society (CNPS) | East Bay chapter of the CNPS (EBCNPS) Fed./Calif.: FE = Fed. Endangered, FT = Fed. Threatened, CE = Calif. Endangered, CR = Calif. Rare CNPS (online as of 2012-01-23): 1B = Rare, threatened or endangered in Calif, 3 = Review List, 4 = Watch List; 0.1 = Seriously endangered in California, 0.2 = Fairly endangered in California EBCNPS (online as of 2012-01-23): *A = Statewide listed rare; A1 = 2 East Bay regions or less; A1x = extirpated; A2 = 3-5 regions; B = 6-9 Inv California Invasive Plant Council Inventory (Cal-IPCI) Invasiveness rating: H = High, L = Limited, M = Moderate, N = Native OL Origin and Longevity. -

Natural Environment Study Addendum

Natural Environment Study Addendum State Route 1 HOV Lanes Tier I Corridor Analysis of High Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) Lanes and Transportation System Management (TSM) Alternatives (05 SCR-1-PM 7.24-16.13) and Tier II Build Project Analysis 41st Avenue to Soquel Avenue/Drive Auxiliary Lanes and Chanticleer Avenue Pedestrian-Bicycle Overcrossing (05 SCR-1-PM 13.5-14.9) EA 0C7300 April 2018 For individuals with sensory disabilities, this document is available in Braille, large print, on audiocassette, or computer disk. To obtain a copy in one of these alternate formats, please call or write to Caltrans, Attn: Matt Fowler, California Department of Transportation – District 5, 50 Higuera Street, San Luis Obispo, CA 93401; 805-542-4603 Voice, or use the California Relay Service 1 (800) 735-2929 (TTY), 1 (800) 735-2929 (Voice), or 711. This page intentionally left blank. State Route 1 HOV Lanes Project Natural Environmental Study Addendum CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 NATURAL ENVIRONMENT STUDY ADDENDUM METHODS .......................................... 1 2 RESOURCES AND IMPACTS EVALUATION............................................................................... 1 2.1 SPECIAL-STATUS PLANT SPECIES ....................................................................................... 1 2.2 SPECIAL STATUS ANIMAL SPECIES .................................................................................... 3 2.2.1 California -

Vascular Plants of Santa Cruz County, California

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST of the VASCULAR PLANTS of SANTA CRUZ COUNTY, CALIFORNIA SECOND EDITION Dylan Neubauer Artwork by Tim Hyland & Maps by Ben Pease CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY, SANTA CRUZ COUNTY CHAPTER Copyright © 2013 by Dylan Neubauer All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without written permission from the author. Design & Production by Dylan Neubauer Artwork by Tim Hyland Maps by Ben Pease, Pease Press Cartography (peasepress.com) Cover photos (Eschscholzia californica & Big Willow Gulch, Swanton) by Dylan Neubauer California Native Plant Society Santa Cruz County Chapter P.O. Box 1622 Santa Cruz, CA 95061 To order, please go to www.cruzcps.org For other correspondence, write to Dylan Neubauer [email protected] ISBN: 978-0-615-85493-9 Printed on recycled paper by Community Printers, Santa Cruz, CA For Tim Forsell, who appreciates the tiny ones ... Nobody sees a flower, really— it is so small— we haven’t time, and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time. —GEORGIA O’KEEFFE CONTENTS ~ u Acknowledgments / 1 u Santa Cruz County Map / 2–3 u Introduction / 4 u Checklist Conventions / 8 u Floristic Regions Map / 12 u Checklist Format, Checklist Symbols, & Region Codes / 13 u Checklist Lycophytes / 14 Ferns / 14 Gymnosperms / 15 Nymphaeales / 16 Magnoliids / 16 Ceratophyllales / 16 Eudicots / 16 Monocots / 61 u Appendices 1. Listed Taxa / 76 2. Endemic Taxa / 78 3. Taxa Extirpated in County / 79 4. Taxa Not Currently Recognized / 80 5. Undescribed Taxa / 82 6. Most Invasive Non-native Taxa / 83 7. Rejected Taxa / 84 8. Notes / 86 u References / 152 u Index to Families & Genera / 154 u Floristic Regions Map with USGS Quad Overlay / 166 “True science teaches, above all, to doubt and be ignorant.” —MIGUEL DE UNAMUNO 1 ~ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ~ ANY THANKS TO THE GENEROUS DONORS without whom this publication would not M have been possible—and to the numerous individuals, organizations, insti- tutions, and agencies that so willingly gave of their time and expertise. -

Thomas Coulter's Californian Exsiccata

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 37 Issue 1 Issue 1–2 Article 2 2019 Plantae Coulterianae: Thomas Coulter’s Californian Exsiccata Gary D. Wallace California Botanic Garden, Claremont, CA Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Wallace, Gary D. (2020) "Plantae Coulterianae: Thomas Coulter’s Californian Exsiccata," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 37: Iss. 1, Article 2. Available at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol37/iss1/2 Aliso, 37(1–2), pp. 1–73 ISSN: 0065-6275 (print), 2327-2929 (online) PLANTAE COULTERIANAE: THOMAS COULTER’S CALIFORNIAN EXSICCATA Gary D. Wallace California Botanic Garden [formerly Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden], 1500 North College Avenue, Claremont, California 91711 ([email protected]) abstract An account of the extent, diversity, and importance of the Californian collections of Thomas Coulter in the herbarium (TCD) of Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland, is presented here. It is based on examination of collections in TCD, several other collections available online, and referenced literature. Additional infor- mation on historical context, content of herbarium labels and annotations is included. Coulter’s collections in TCD are less well known than partial duplicate sets at other herbaria. He was the first botanist to cross the desert of southern California to the Colorado River. Coulter’s collections in TCD include not only 60 vascular plant specimens previously unidentified as type material but also among the first moss andmarine algae specimens known to be collected in California. A list of taxa named for Thomas Coulter is included. -

A Checklist of Vascular Plants Endemic to California

Humboldt State University Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University Botanical Studies Open Educational Resources and Data 3-2020 A Checklist of Vascular Plants Endemic to California James P. Smith Jr Humboldt State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Smith, James P. Jr, "A Checklist of Vascular Plants Endemic to California" (2020). Botanical Studies. 42. https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps/42 This Flora of California is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources and Data at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Botanical Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A LIST OF THE VASCULAR PLANTS ENDEMIC TO CALIFORNIA Compiled By James P. Smith, Jr. Professor Emeritus of Botany Department of Biological Sciences Humboldt State University Arcata, California 13 February 2020 CONTENTS Willis Jepson (1923-1925) recognized that the assemblage of plants that characterized our flora excludes the desert province of southwest California Introduction. 1 and extends beyond its political boundaries to include An Overview. 2 southwestern Oregon, a small portion of western Endemic Genera . 2 Nevada, and the northern portion of Baja California, Almost Endemic Genera . 3 Mexico. This expanded region became known as the California Floristic Province (CFP). Keep in mind that List of Endemic Plants . 4 not all plants endemic to California lie within the CFP Plants Endemic to a Single County or Island 24 and others that are endemic to the CFP are not County and Channel Island Abbreviations . -

Interim-Programmatic Habitat Conservation Plan (IPHCP), and the Associated Implementing Agreement

Interim‐Programmatic Habitat Conservation Plan for the Endangered Mount Hermon June Beetle and Ben Lomond Spineflower Prepared for: Citizens of the City of Scotts Valley and County of Santa Cruz Proposing Small-Scale Residential Development Projects in the Zayante Sandhills, Santa Cruz County, California Prepared by: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Ventura, California; Santa Cruz County; and City of Scotts Valley June 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 10 1.0 Project Background ....................................................................................................... 10 1.1 Scope of the Interim Programmatic HCP/Permit Duration .......................................... 15 1.2 Regulatory Framework ................................................................................................. 15 1.2.1 Federal Endangered Species Act .......................................................................... 15 1.2.2 National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) ........................................................ 17 1.2.3 California Endangered Species Act ...................................................................... 18 1.2.4 California Environmental Quality Act .................................................................. 18 1.2.5 Sensitive Habitat Protection Ordinance ................................................................ 18 1.2.6 Tree Removal Ordinances .................................................................................... -

Rio Park-Larson Field

CITY OF CARMEL‐BY‐THE‐SEA R IO PARK/LARSON F IELD PATHWAY PROJECT DRAFT INITIAL STUDY/MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION VOLUME II: APPENDICES CITY OF CARMEL‐BY‐THE‐SEA P.O. BOX G E/S MONTE VERDE BETWEEN OCEAN AND 7TH CARMEL, CA 93921 Prepared by: 60 GARDEN COURT, SUITE 230 MONTEREY, CA 93940 SEPTEMBER 2015 C ITY OF CARMEL‐ BY‐ THE‐S EA R IO P ARK/ L ARSON F IELD P ATHWAY P ROJECT DRAFT INITIAL STUDY/ MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION VOLUME II: APPENDICES Prepared for: CITY OF CARMEL‐BY‐THE‐SEA P.O. BOX G E/S MONTE VERDE BETWEEN OCEAN AND 7TH CARMEL, CA 93921 Prepared by: 60 GARDEN COURT, SUITE 230 MONTEREY, CA 93940 SEPTEMBER 2015 Table of Contents Appendices Appendix A1 Biological Resources ‐ Database Query Results Appendix A2 Biological Resources ‐ Local Policy Consistency Table Appendix A3 Biological Resources – Species Summary Table Appendix B Archaeological Records Search and Site Reconnaissance Appendix C Traffic Analysis APPENDICES Appendix A1 Biological Resources - Database Query Results Michael Baker International IMAPS Print Preview Page 1 of 13 CNDDB 9-Quad Species List 234 records. CA Element Common Federal State CDFW Rare Quad Quad Scientific Name Element Code Data Status Taxonomic Sort Type Name Status Status Status Plant Code Name Rank Animals - California Amphibians - Animals - Ambystoma Mt. Mapped and tiger AAAAA01180 Threatened Threatened SSC - 3612147 Ambystomatidae Amphibians californiense Carmel Unprocessed salamander - Ambystoma californiense Animals - California Amphibians - Animals - Ambystoma Mapped and tiger AAAAA01180 -

Current Issue of Arnoldia

The Magazine of the Arnold Arboretum VOLUME 78 • NUMBER 3 The Magazine of the Arnold Arboretum VOLUME 78 • NUMBER 3 • 2021 CONTENTS Arnoldia (ISSN 0004–2633; USPS 866–100) 2 Building a Comprehensive Plant Collection is published quarterly by the Arnold Arboretum Jeffrey D. Carstens of Harvard University. Periodicals postage paid at Boston, Massachusetts. 5 A Conservation SOS: Polygonum hickmanii Holly Forbes Annual subscriptions are $20.00 domestic or $25.00 international, payable in U.S. dollars. 7 An Unusual Autumn at the Dana Greenhouses Subscribe and purchase back issues online at Tiffany Enzenbacher https://arboretum.harvard.edu/arnoldia/ or send orders, remittances, change-of-address notices, 10 A Brief History of Juglandaceae and all other subscription-related communica- Jonas Frei tions to Circulation Manager, Arnoldia, Arnold Arboretum, 125 Arborway, Boston, MA 02130- 18 Discovering the Majestic Mai Hing Sam of Laos 3500. Telephone 617.524.1718; fax 617.524.1418; Gretchen C. Coffman e-mail [email protected] 28 Backyard Climate Solutions Arnold Arboretum members receive a subscrip- Edward K. Faison tion to Arnoldia as a membership benefit. To become a member or receive more information, 38 A New Look at Boston Common Trees please call Wendy Krauss at 617.384.5766 or Kelsey Allen and W. Wyatt Oswald email [email protected] 42 Case of the Anthropocene Postmaster: Send address changes to Jonathan Damery Arnoldia Circulation Manager 44 Planting Edo: Pinus thunbergii The Arnold Arboretum Rachel Saunders 125 Arborway Boston, MA 02130–3500 Front and back cover: Jonas Frei’s collection of walnut family fruits includes a disc-shaped wheel wingnut (Cyc- Jonathan Damery, Editor locarya paliurus, back cover) among other more familiar- David Hakas, Editorial Intern Andy Winther, Designer looking species.