W Ho Killed M G Rover?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

*2021 British Car Showdown Rules.Docx

BRITISH CAR SHOWDOWN Saturday, June 26, 2021 Welcome to the British Car Showdown at Mid-Ohio Sports Car Course! We appreciate your efforts to prepare for this event. This show will be a popular vote format among the participants. Please make sure you have picked up a voting ballot from registration. We want everyone to have fun, so every effort will be made to keep this show low-key and as enjoyable as possible. ________________________________________________________________________________________________ IMPORTANT INFORMATION . PLEASE READ! 1) PARKING: Please park your car in the designated class in which you would like your car judged. There is also a general parking corral for miscellaneous British vehicles. 2) JUDGING CLASSES: Listed below are all the classes for which awards will be presented. First, second and third place awards will be presented to each class. Class Awards Austin Healey 100 & 3000 MINI Classic (1959-2000) Austin Healey Sprite / MG Midget MINI New (2001-Present) Griffith / TVR Morgan Jaguar Sedan Spitfire & GT6 Jaguar XK & E-Type Sunbeam Lotus Triumph TR2, TR3, TR4 MGB & MGC Triumph TR6, TR7, TR8 MG-T Misc. British Additional Awards Most Miles Driven to Mid-Ohio Best of Show (Peoples Choice & Judges Choice) 3) REGISTRATION: Please check in at the show registration tent near the super pavilion. You will receive a BLUE registration form for your car and a commemorative souvenir. Please fill out both parts of the registration form and turn in the bottom half at Registration. You will need to display the top half of the registration form on your windshield to enter the track for the parade lap on Saturday. -

ALL-NEW DISCOVERY FIRST EDITION Ever Since the First Land Rover Vehicle Was Conceived in 1947, We Have Built Vehicles That Challenge What Is Possible

ALL-NEW DISCOVERY FIRST EDITION Ever since the first Land Rover vehicle was conceived in 1947, we have built vehicles that challenge what is possible. These in turn have challenged their owners to explore new territories and conquer difficult terrains. Our vehicles epitomise the values of the designers and engineers who have created them. Each one instilled with iconic British design cues, delivering capability with composure. Which is how we continue to break new ground, defy conventions and encourage each other to go further. Land Rover truly enables you to make more of your world, to go above and beyond. “THE FIRST EDITION GIVES CUSTOMERS THE OPPORTUNITY TO HAVE A UNIQUE VERSION CONTENTS OF THE NEW DISCOVERY. WITH INTRODUCTION STUNNING DESIGN, EXQUISITE All-New Discovery First Edition. DETAILS AND EFFORTLESS Following a Proud History. 4 VERSATILITY, THIS COMPELLING The Concept of All-New Discovery First Edition 5 VEHICLE REDEFINES THE All-New Discovery First Edition – The Facts 6 MEANING OF DESIRABILITY.” DESIGN Exterior 7 Professor Gerry McGovern. Interior 10 Land Rover Design Director and Chief Creative Officer. Seven Full-Size Seats 12 Remote Intelligent Seat Fold 12 DRIVING TECHNOLOGY Permanent 4 Wheel Drive Systems 13 Terrain Response 2 13 All Terrain Progress Control 13 Towing Aids 14 CONNECTIVITY. ENTERTAINMENT. COMFORT Land Rover InControl 15 Meridian™ Sound System 18 ENGINES Engine Performance 20 Diesel Engine 21 Petrol Engine 21 SPECIFICATIONS Choose Your Colour 22 Choose Your Wheels 23 Choose Your Interior 24 Standard and Optional Features 25 Land Rover Approved Accessories 26 TECHNICAL DETAILS 28 A WORLD OF LAND ROVER 30 Vehicles shown are from the Land Rover global range. -

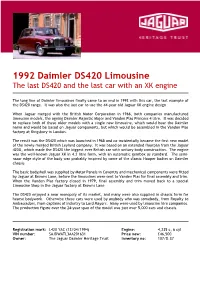

1992 Daimler DS420 Limousine the Last DS420 and the Last Car with an XK Engine

1992 Daimler DS420 Limousine The last DS420 and the last car with an XK engine The long line of Daimler limousines finally came to an end in 1992 with this car, the last example of the DS420 range. It was also the last car to use the 44-year old Jaguar XK engine design When Jaguar merged with the British Motor Corporation in 1966, both companies manufactured limousine models, the ageing Daimler Majestic Major and Vanden Plas Princess 4 litre. It was decided to replace both of these older models with a single new limousine, which would bear the Daimler name and would be based on Jaguar components, but which would be assembled in the Vanden Plas factory at Kingsbury in London. The result was the DS420 which was launched in 1968 and co-incidentally became the first new model of the newly-merged British Leyland company. It was based on an extended floorpan from the Jaguar 420G, which made the DS420 the biggest ever British car with unitary body construction. The engine was the well-known Jaguar XK in 4.2 litre form, with an automatic gearbox as standard. The semi- razor edge style of the body was probably inspired by some of the classic Hooper bodies on Daimler chassis The basic bodyshell was supplied by Motor Panels in Coventry and mechanical components were fitted by Jaguar at Browns Lane, before the limousines were sent to Vanden Plas for final assembly and trim. When the Vanden Plas factory closed in 1979, final assembly and trim moved back to a special Limousine Shop in the Jaguar factory at Browns Lane The DS420 enjoyed a near monopoly of its market, and many were also supplied in chassis form for hearse bodywork. -

Plant Tour Information. Information on Plant Tours at the Mini Plant Oxford

Werk Oxford PLANT TOUR INFORMATION. INFORMATION ON PLANT TOURS AT THE MINI PLANT OXFORD. Around 10,000 people visit No animals. Minimum age. Plant Oxford every year to see Pets or animals of any We differentiate between two booking how MINIs are made. Please kind are not allowed. types, Exclusive group and public. note the following information For an exclusive group children aged before booking a plant tour. Maximum group size. between 10-13 must be accompanied The maximum size for one group by an adult, with a maximum of Booking in advance. is 15 persons. The tour is planned two children to each adult. For Booking in advance is essential. according to the number of people ages 14-18 the ratio is 14 children Plant tours are offered only on days you have registered. Please note that to one adult. For our public tours with running production (normally the tour is held for the registered children aged between 10-17 must be Monday to Friday). Plant tours number of visitors only. Please accompanied by an adult on a ratio usually take place at 9:00/9:30, inform our Service Centre in case the of two children to one adult. To avoid 13:15/13:30 and 16:30/17:30. number of participants has changed. disappointment, please make sure to comply with these requirements. Admission Fee. Filming and photographing. Visitors not complying will not be Reduced admission fee with a Photography and filming is strictly able to take tours as a result. relevant proof: Children and young prohibited in production areas. -

Classic Vehicle Auctionauctionauction

Classic Vehicle AuctionAuctionAuction Friday 28th April 2017 Commencing at 11AM Being held at: South Western Vehicle Auctions Limited 61 Ringwood Road, Parkstone, Poole, Dorset, BH14 0RG Tel:+44(0)1202745466 swva.co.ukswva.co.ukswva.co.uk £5 CLASSIC VEHICLE AUCTIONS EXTRA TERMS & CONDITIONS NB:OUR GENERAL CONDITIONS OF SALE APPLY THE ESTIMATES DO NOT INCLUDE BUYERS PREMIUM COMMISSION – 6% + VAT (Minimum £150 inc VAT) BUYERS PREMIUM – 8% + VAT (Minimum £150 inc VAT) ONLINE AND TELEPHONE BIDS £10.00 + BUYERS PREMIUM + VAT ON PURCHASE 10% DEPOSIT, MINIMUM £500, PAYABLE ON THE FALL OF THE HAMMER AT THE CASH DESK. DEPOSITS CAN BE PAID BY DEBIT CARD OR CASH (Which is subject to 1.25% Surcharge) BALANCES BY NOON ON THE FOLLOWING MONDAY. BALANCES CAN BE PAID BY DEBIT CARD, BANK TRANSFER, CASH (Which is subject to 1.25% surcharge), OR CREDIT CARD (Which is subject to 3.5% surcharge) ALL VEHICLES ARE SOLD AS SEEN PROSPECTIVE PURCHASERS ARE ADVISED TO SATISFY THEMSELVES AS TO THE ACCURACY OF ANY STATEMENT MADE, BE THEY STATEMENTS OF FACT OR OPINION. ALL MILEAGES ARE SOLD AS INCORRECT UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED CURRENT ENGINE AND CHASSIS NUMBERS ARE SUPPLIED BY HPI. ALL VEHICLES MUST BE COLLECTED WITHIN 3 WEEKS, AFTER 3 WEEKS STORAGE FEES WILL INCUR Lot 1 BENTLEY - 4257cc ~ 1949 LLG195 is the second Bentley (see lot 61) that the late Mr Wells started to make into a special in the 1990's. All the hard work has been done ie moving the engine back 18 inches, shortening the propshaft and making a new bulkhead, the aluminium special body is all there bar a few little bits which need finishing. -

Automotive Sector in Tees Valley

Invest in Tees Valley A place to grow your automotive business Invest in Tees Valley Recent successes include: Tees Valley and the North East region has April 2014 everything it needs to sustain, grow and Nifco opens new £12 million manufacturing facility and Powertrain and R&D plant develop businesses in the automotive industry. You just need to look around to June 2014 see who is already here to see the success Darchem opens new £8 million thermal of this growing sector. insulation manufacturing facility With government backed funding, support agencies September 2014 such as Tees Valley Unlimited, and a wealth of ElringKlinger opens new £10 million facility engineering skills and expertise, Tees Valley is home to some of the best and most productive facilities in the UK. The area is innovative and forward thinking, June 2015 Nifco announces plans for a 3rd factory, helping it to maintain its position at the leading edge boosting staff numbers to 800 of developments in this sector. Tees Valley holds a number of competitive advantages July 2015 which have helped attract £1.3 billion of capital Cummins’ Low emission bus engine production investment since 2011. switches from China back to Darlington Why Tees Valley should be your next move Manufacturing skills base around half that of major cities and a quarter of The heritage and expertise of the manufacturing those in London and the South East. and engineering sector in Tees Valley is world renowned and continues to thrive and innovate Access to international markets Major engineering companies in Tees Valley export Skilled and affordable workforce their products around the world with our Tees Valley has a ready skilled labour force excellent infrastructure, including one of the which is one of the most affordable and value UK’s leading ports, the quickest road connections for money in the UK. -

P 01.Qxd 6/30/2005 2:00 PM Page 1

p 01.qxd 6/30/2005 2:00 PM Page 1 June 27, 2005 © 2005 Crain Communications GmbH. All rights reserved. €14.95; or equivalent 20052005 GlobalGlobal MarketMarket DataData BookBook Global Vehicle Production and Sales Regional Vehicle Production and Sales History and Forecast Regional Vehicle Production and Sales by Model Regional Assembly Plant Maps Top 100 Global Suppliers Contents Global vehicle production and sales...............................................4-8 2005 Western Europe production and sales..........................................10-18 North America production and sales..........................................19-29 Global Japan production and sales .............30-37 India production and sales ..............39-40 Korea production and sales .............39-40 China production and sales..............39-40 Market Australia production and sales..........................................39-40 Argentina production and sales.............45 Brazil production and sales ....................45 Data Book Top 100 global suppliers...................46-50 Mary Raetz Anne Wright Curtis Dorota Kowalski, Debi Domby Senior Statistician Global Market Data Book Editor Researchers [email protected] [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] Paul McVeigh, News Editor e-mail: [email protected] Irina Heiligensetzer, Production/Sales Support Tel: (49) 8153 907503 CZECH REPUBLIC: Lyle Frink, Tel: (49) 8153 907521 Fax: (49) 8153 907425 e-mail: [email protected] Tel: (420) 606-486729 e-mail: [email protected] Georgia Bootiman, Production Editor e-mail: [email protected] USA: 1155 Gratiot Avenue, Detroit, MI 48207 Tel: (49) 8153 907511 SPAIN, PORTUGAL: Paulo Soares de Oliveira, Tony Merpi, Group Advertising Director e-mail: [email protected] Tel: (35) 1919-767-459 Larry Schlagheck, US Advertising Director www.automotivenewseurope.com Douglas A. Bolduc, Reporter e-mail: [email protected] Tel: (1) 313 446-6030 Fax: (1) 313 446-8030 Tel: (49) 8153 907504 Keith E. -

Competition and the Workplace in the British Automobile Industry, 1945

Competition and the Workplace in the British Automobile Industry. 1945-1988 Steven To!!iday Harvard University This paper considers the impact of industrial relations on competitive performance. Recent changesin markets and technology have increased interest in the interaction of competitive strategies and workplace management and in particular have highlighted problems of adaptability in different national systems. The literature on the British automobile industry offers widely divergent views on these issues. One which has gained widespread acceptance is that defects at the level of industrial relations have seriously impaired company performance. Versions of this view have emanated from a variety of sources. The best known are the accountsof CPRS and Edwardes [3, 10], which argue that the crisis of the industry stemmed in large part from restrictive working practices, inadequate labor effort, excessive labor costs, and worker militancy. From a different vantage point, Lewchuk has recently argued that the long-run post-War production problems of the industry should be seen as the result of a conflict between the requirements of new American technology for greater direct management control of the production processand the constraints resulting from shopfloor "production institutions based on earlier craft technology." This contradiction was only resolved by the reassertion of managerial control in the 1980s and the "belated" introduction of Fordist techniques of labor management [13, 91. On the other hand Williams et al. have argued that industrial relations have been of only minor significance in comparison to other causes of market failure [30, 31], and Marsden et al. [15] and Willman and Winch [35] both concur that the importance of labor relations problems has been consistently magnified out of proportion. -

British Motor Industry Heritage Trust

British Motor Industry Heritage Trust COLLECTIONS DEVELOPMENT POLICY British Motor Museum Banbury Road, Gaydon, Warwick CV35 0BJ svl/2016 This Collections Development Policy relates to the collections of motor cars, motoring related artefacts and archive material held at the British Motor Museum, Gaydon, Warwick, United Kingdom. Name of governing body: British Motor Industry Heritage Trust (BMIHT) Date on which this policy was approved by governing body: 13th April 2016 The Collections Development Policy will be published and reviewed from time to time, at least once every five years. The anticipated date on which this policy will be reviewed is December 2019. Arts Council England will be notified of any changes to the Collections Development Policy and the implication of any such changes for the future of collections. 1. Relationship to other relevant polices/plans of the organisation: 1.1 BMIHT’s Statement of Purpose is: To collect, conserve, research and display for the benefit of the nation, motor vehicles, archives, artefacts and ancillary material relating to the motor industry in Britain. To seek the opportunity to include motor and component manufacturers in Britain. To promote the role the motor industry has played in the economic, technical and social development of both Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The motor industry in Britain is defined by companies that have manufactured or assembled vehicles or components within the United Kingdom for a continuous period of not less than five years. 1.2 BMIHT’s Board of Trustees will ensure that both acquisition and disposal are carried out openly and with transparency. 1.3 By definition, BMIHT has a long-term purpose and holds collections in trust for the benefit of the public in relation to its stated objectives. -

Report on the Affairs of Phoenix Venture Holdings Limited, Mg Rover Group Limited and 33 Other Companies Volume I

REPORT ON THE AFFAIRS OF PHOENIX VENTURE HOLDINGS LIMITED, MG ROVER GROUP LIMITED AND 33 OTHER COMPANIES VOLUME I Gervase MacGregor FCA Guy Newey QC (Inspectors appointed by the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry under section 432(2) of the Companies Act 1985) Report on the affairs of Phoenix Venture Holdings Limited, MG Rover Group Limited and 33 other companies by Gervase MacGregor FCA and Guy Newey QC (Inspectors appointed by the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry under section 432(2) of the Companies Act 1985) Volume I Published by TSO (The Stationery Office) and available from: Online www.tsoshop.co.uk Mail, Telephone, Fax & E-mail TSO PO Box 29, Norwich, NR3 1GN Telephone orders/General enquiries: 0870 600 5522 Fax orders: 0870 600 5533 E-mail: [email protected] Textphone 0870 240 3701 TSO@Blackwell and other Accredited Agents Customers can also order publications from: TSO Ireland 16 Arthur Street, Belfast BT1 4GD Tel 028 9023 8451 Fax 028 9023 5401 Published with the permission of the Department for Business Innovation and Skills on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown Copyright 2009 All rights reserved. Copyright in the typographical arrangement and design is vested in the Crown. Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to the Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU. First published 2009 ISBN 9780 115155239 Printed in the United Kingdom by the Stationery Office N6187351 C3 07/09 Contents Chapter Page VOLUME -

Annual Report 2018/19 (PDF)

JAGUAR LAND ROVER AUTOMOTIVE PLC Annual Report 2018/19 STRATEGIC REPORT 1 Introduction THIS YEAR MARKED A SERIES OF HISTORIC MILESTONES FOR JAGUAR LAND ROVER: TEN YEARS OF TATA OWNERSHIP, DURING WHICH WE HAVE ACHIEVED RECORD GROWTH AND REALISED THE POTENTIAL RATAN TATA SAW IN OUR TWO ICONIC BRANDS; FIFTY YEARS OF THE EXTRAORDINARY JAGUAR XJ, BOASTING A LUXURY SALOON BLOODLINE UNLIKE ANY OTHER; AND SEVENTY YEARS SINCE THE FIRST LAND ROVER MOBILISED COMMUNITIES AROUND THE WORLD. TODAY, WE ARE TRANSFORMING FOR TOMORROW. OUR VISION IS A WORLD OF SUSTAINABLE, SMART MOBILITY: DESTINATION ZERO. WE ARE DRIVING TOWARDS A FUTURE OF ZERO EMISSIONS, ZERO ACCIDENTS AND ZERO CONGESTION – EVEN ZERO WASTE. WE SEEK CONSCIOUS REDUCTIONS, EMBRACING THE CIRCULAR ECONOMY AND GIVING BACK TO SOCIETY. TECHNOLOGIES ARE CHANGING BUT THE CORE INGREDIENTS OF JAGUAR LAND ROVER REMAIN THE SAME: RESPONSIBLE BUSINESS PRACTICES, CUTTING-EDGE INNOVATION AND OUTSTANDING PRODUCTS THAT OFFER OUR CUSTOMERS A COMPELLING COMBINATION OF THE BEST BRITISH DESIGN AND ENGINEERING INTEGRITY. CUSTOMERS ARE AT THE HEART OF EVERYTHING WE DO. WHETHER GOING ABOVE AND BEYOND WITH LAND ROVER, OR BEING FEARLESSLY CREATIVE WITH JAGUAR, WE WILL ALWAYS DELIVER EXPERIENCES THAT PEOPLE LOVE, FOR LIFE. The Red Arrows over Solihull at Land Rover’s 70th anniversary celebration 2 JAGUAR LAND ROVER AUTOMOTIVE PLC ANNUAL REPORT 2018/19 STRATEGIC REPORT 3 Introduction CONTENTS FISCAL YEAR 2018/19 AT A GLANCE STRATEGIC REPORT FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 3 Introduction 98 Independent Auditor’s report to the members -

5Th Annual Classic Go-Kart Challenge

May, 2005 vol. IV, no. 5 5th Annual Classic Go-Kart Challenge Which club took home the trophy? See page 3 Marque Clubs of the Upper Midwest British Iron Society of (www.mini-sota.com) MAY, 2005 Greater Fargo (701-293- VOLUME IV, ISSUE 5 MINI-sota Motoring Society 6882) ([email protected]) PUBLISHER Citroën Car Club of Minne- Minnesota Morgans Vintage Enterprises sota (www.citroenmn.com) ([email protected]) EDITOR Glacier Lakes Quatro Club Minnesota SAAB Club Andy Lindberg (www.glacierlakesqclub.org) (www.mnsaabclub.org) Minnesota Triumphs SENIOR COPY EDITOR Jaguar Club of Minnesota (www.mntriumphs.org) Linda Larson (www.jaguarminnesota.org) Lotus Eaters (TYPE45@aol. Nordstern Porsche Club (www. CONTRIBUTORS com) nordstern.org) Bob Groman Lotus Owners of the North - North Star BMW Car Club SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION LOON ([email protected]) (www.northstarbmw.org) To subscribe, send e-mail address to Pagoda Club of Minnesota andylindberg@ earthlink.net with the Mercedes Benz Club of secret message, “Subscribe me to America, Twin Cities (651-452-2807) the monthly.” Section (www.mbca-tc.org) The Regulars Twin Cities Vintage Scooter Club SUBSCRIPTION RATES Metropolitans from Minne- U.S. One Year: free; Two Years: free; (www.minnescoota.com) One year foreign: free; Overseas: sota (www.metropolitansfrom free. Subject to change with or minnesota.com) Stella del Nord Alfa Romeo without notice. Owners Club (esolstad@ Minnesota Austin-Healey pressenter.com) ADDRESS CHANGES Club (www.mnhealey.com) To insure no issues are missed, send Twin Cities VW Club e-mail message to Minnesota Ferrari Club (www.twincitiesvwclub.com) ([email protected]) [email protected] Vintage Sports Car Racing COPYRIGHT 2005 by IMM.