Improving the Resilience of Mixed-Farm Systems to Pending Climate Change in Far Western Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Security Bulletin 29

Nepal Food Security Bulletin Issue 29, October 2010 The focus of this edition is on the Mid and Far Western Hill and Mountain region Situation summary Figure 1. Percentage of population food insecure* 26% This Food Security Bulletin covers the period July-September and is focused on the Mid and Far Western Hill and Mountain (MFWHM) 24% region (typically the most food insecure region of the country). 22% July – August is an agricultural lean period in Nepal and typically a season of increased food insecurity. In addition, flooding and 20% landslides caused by monsoon regularly block transportation routes and result in localised crop losses. 18 % During the 2010 monsoon 1,600 families were reportedly 16 % displaced due to flooding, the Karnali Highway and other trade 14 % routes were blocked by landslides and significant crop losses were Oct -Dec Jan-M ar Apr-Jun Jul-Sep Oct -Dec Jan-M ar Apr-Jun Jul-Sep reported in Kanchanpur, Dadeldhura, western Surkhet and south- 08 09 09 09 09 10 10 10 eastern Udayapur. NeKSAP District Food Security Networks in MFWHM districts Rural Nepal Mid-Far-Western Hills&Mountains identified 163 VDCs in 12 districts that are highly food insecure. Forty-four percent of the population in Humla and Bajura are reportedly facing a high level of food insecurity. Other districts with households that are facing a high level of food insecurity are Mugu, Kalikot, Rukum, Surkhet, Achham, Doti, Bajhang, Baitadi, Dadeldhura and Darchula. These households have both very limited food stocks and limited financial resources to purchase food. Most households are coping by reducing consumption, borrowing money or food and selling assets. -

Food Security Bulletin - 21

Food Security Bulletin - 21 United Nations World Food Programme FS Bulletin, November 2008 Food Security Monitoring and Analysis System Issue 21 Highlights Over the period July to September 2008, the number of people highly and severely food insecure increased by about 50% compared to the previous quarter due to severe flooding in the East and Western Terai districts, roads obstruction because of incessant rainfall and landslides, rise in food prices and decreased production of maize and other local crops. The food security situation in the flood affected districts of Eastern and Western Terai remains precarious, requiring close monitoring, while in the majority of other districts the food security situation is likely to improve in November-December due to harvesting of the paddy crop. Decreased maize and paddy production in some districts may indicate a deteriorating food insecurity situation from January onwards. this period. However, there is an could be achieved through the provision Overview expectation of deteriorating food security of return packages consisting of food Mid and Far-Western Nepal from January onwards as in most of the and other essentials as well as A considerable improvement in food Hill and Mountain districts excessive agriculture support to restore people’s security was observed in some Hill rainfall, floods, landslides, strong wind, livelihoods. districts such as Jajarkot, Bajura, and pest diseases have badly affected In the Western Terai, a recent rapid Dailekh, Rukum, Baitadi, and Darchula. maize production and consequently assessment conducted by WFP in These districts were severely or highly reduced food stocks much below what is November, revealed that the food food insecure during April - July 2008 normally expected during this time of the security situation is still critical in because of heavy loss in winter crops, year. -

Download 4.06 MB

Environmental Compliance Monitoring Report Semi-Annual Report Project Number: 44214-024 Grant Number: 0357-NEP July 2020 Nepal: Building Climate Resilience of Watersheds in Mountain Eco-Regions Project Prepared by the Government of Nepal for the Asian Development Bank. This environmental Compliance Monitoring Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Government of Nepal Department of Forests and Soil Conservation Building Climate Resilience of Watersheds in Mountain Eco-Regions (BCRWME) Project (ADB Loan/Grant No.: GO357/0358-NEP) Semiannual Environemntal Monitoring Report of BCRWME Sub-projects (January to June 2020) Preparaed By BCRWME Project Project Management Unit Dadeldhura July, 2020 ABBREVIATION ADB : Asian Development Bank BCRWME : Building Climate Resilience of Watersheds in Mountain Eco- Regions BOQ : Bills of Quantity CDG : Community Development Group CFUG : Community Forest User Group CO : Community Organizer CPC : Consultation, Participation and Communications (Plan) CS : Construction Supervisor DDR : Due Diligence -

Khaptad Chhededaha Rural Municipality Invitation for Bids

Khaptad Chhededaha Rural Municipality Office Of The Municipal Executive Dogadi, Bajura Far-Western Province, Nepal Invitation for Bids IFB No: 1/075/076 Date of publication: 2075/12/29 Method of Procurement: NCB, Eligibility Procedure 1. Khaptad Chhetedaha Rural Municipality Office invites sealed Bids from all eligible Nepalese Bidders for Construction & Maintenance of Following Roads with construction detail as follows. (Name and Identification no of Contract are as follows.) Estimated Bid Cost Contract Bid S. Amount (NRS.) Security of Bid Identification Description of Work Security N. [Excluding VAT Validity Document No: amount & Contingencies] Period (NRs.) KCRM/NCB/ Chhededaha-Thamlekh 1 42,97,362.11 1,25,000.00 3,000.00 W/R/01/2075-076 Sadak Stharunnati KCRM/NCB/ Dungrikhola-Baddaune 2 43,06,503.61 1,25,000.00 3,000.00 W/R/02/2075-076 Sadak Stharunnati KCRM/NCB/ Adharikhola-Chhadipatal 3 43,05,041.53 1,25,000.00 3,000.00 W/R/03/2075-076 Sadak Stharunnati KCRM/NCB/ Atichaur-Chhededaha 4. 43,08,802.32 1,25,000.00 3,000.00 W/R/04/2075-076 Stharunnati Road Maurekhola- KCRM/NCB/ 5. Jayabageshwori-Raan- 87,94,058.32 2,55,000.00 last date of bid submission 3,000.00 W/R/05/2075-076 up to 120 days from the Validity Singada Sadak Stharunnati. 2. Eligible Bidders may obtain further information and inspect the Bidding Documents at the Khaptad-Chhededaha Rural Municipality office Bajura, Email Address: [email protected], Contact No: 096-690801 or may visit PPMO website www.bolpatra.gov.np. -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Pray for Nepal

Pray for Nepal Bajhang Bajura Doti Achham Kailali Seti, Bajura Greetings in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, Thank-You for committing to join with us to pray for the well-being of every village in our wonderful country. Jesus modeled his love for every village when he was going from one city and village to another with his disciples. Next, Jesus would mentor his disciples to do the same by sending them out to all the villages. Later, he would monitor the work of the disciples and the 70 as they were sent out two-by-two to all the villages. (Luke 8-10) But, how can we pray for the 3,984 VDCs in our Country? In the time of Nehemiah, his brother brought him news that the walls of Jerusalem were torn down. The wall represented protection, safety, blessing, and a future. Nehemiah prayed, fasted, and repented for the sins of the people. God answered Nehemiah’s prayers. The huge task to re-build the walls became possible through God’s blessings, each person building in front of their own houses, and the builders continuing even in the face of great persecution. For us, each village is like a brick in the wall. Let us pray for every village so that there are no holes in the wall. Each person praying for the villages in their respective areas would ensure a systematic approach so that all the villages of the state would be covered in prayer. Some have asked, “How do you eat an Elephant?” (How do you work on a giant project?) Others have answered, “One bite at a time.” (One step at a time - in small pieces). -

Decentralized Rural Infrastructure and Livelihood Project- Additional Financing

Indigenous People Planning Document Due Diligence Report Loan Number: 2796 and Grant Number: 0267 NEP May 2012 Nepal: Decentralized Rural Infrastructure and Livelihood Project- Additional Financing Barabis-Delta Bazar Road Subproject Bajura Prepared by the Government of Nepal The Due Diligence Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. District Development Committee, Bajura Office of District Development Committee, Bajura District Technical Office, Bajura Decentralized Rural Infrastructure and Livelihood Project-Additional Financing (DRILP-AF) District Project Office, Bajura Decentralized Rural Infrastructure and Livelihood Project-Additional Financing (DRILP-AF) Detailed Project Report Barabis-Delta Bazar Road Sub Project Section III: Safeguards Volume III: Impact Screening Report on Indigenous Peoples May 2012 TABLE OF CONTENT Page No. 1. Project Background………………………………………………………………………… 1 2. Road Sub-project’s Background…………………………………………………………. 1 3. Demographic information of ZOI…………………………………………………………. 2 4. Identification of IPs…………………………………………………………………………. 3 5. Sub-project activity………………………………………………………………………… 4 6. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………… 4 ANNEXES Annex 1: Indigenous People Screening checklist Annex 2: Meeting minute about consultation with stakeholders Annex 3: Certified letters from VDCs 1 1. PROJECT BACKGROUND 1. The Decentralized Rural Infrastructure and Livelihood Project-Additional -

TSLC PMT Result

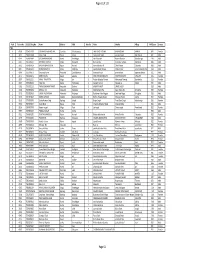

Page 62 of 132 Rank Token No SLC/SEE Reg No Name District Palika WardNo Father Mother Village PMTScore Gender TSLC 1 42060 7574O15075 SOBHA BOHARA BOHARA Darchula Rithachaupata 3 HARI SINGH BOHARA BIMA BOHARA AMKUR 890.1 Female 2 39231 7569013048 Sanju Singh Bajura Gotree 9 Gyanendra Singh Jansara Singh Manikanda 902.7 Male 3 40574 7559004049 LOGAJAN BHANDARI Humla ShreeNagar 1 Hari Bhandari Amani Bhandari Bhandari gau 907 Male 4 40374 6560016016 DHANRAJ TAMATA Mugu Dhainakot 8 Bali Tamata Puni kala Tamata Dalitbada 908.2 Male 5 36515 7569004014 BHUVAN BAHADUR BK Bajura Martadi 3 Karna bahadur bk Dhauli lawar Chaurata 908.5 Male 6 43877 6960005019 NANDA SINGH B K Mugu Kotdanda 9 Jaya bahadur tiruwa Muga tiruwa Luee kotdanda mugu 910.4 Male 7 40945 7535076072 Saroj raut kurmi Rautahat GarudaBairiya 7 biswanath raut pramila devi pipariya dostiya 911.3 Male 8 42712 7569023079 NISHA BUDHa Bajura Sappata 6 GAN BAHADUR BUDHA AABHARI BUDHA CHUDARI 911.4 Female 9 35970 7260012119 RAMU TAMATATA Mugu Seri 5 Padam Bahadur Tamata Manamata Tamata Bamkanda 912.6 Female 10 36673 7375025003 Akbar Od Baitadi Pancheswor 3 Ganesh ram od Kalawati od Kalauti 915.4 Male 11 40529 7335011133 PRAMOD KUMAR PANDIT Rautahat Dharhari 5 MISHRI PANDIT URMILA DEVI 915.8 Male 12 42683 7525055002 BIMALA RAI Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Man Bahadur Rai Gauri Maya Rai Ghodghad 915.9 Female 13 42758 7525055016 SABIN AALE MAGAR Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Raj Kumar Aale Magqar Devi Aale Magar Ghodghad 915.9 Male 14 42459 7217094014 SOBHA DHAKAL Dolakha GhangSukathokar 2 Bishnu Prasad Dhakal -

Food Security Bulletin 26

Nepal Food Security Bulletin Issue 26, October - December 2009 Situation Summary Figure 1. Percentage of population food insecure • The recent completion of the major harvest period of the year has improved the overall short-term food security situation 17.0% across the country. At a national level WFP household surveys revealed that food stocks and consumption levels have seen 16.5% an improvement since late last year when the harvest begun. • However, a number of districts in the Karnali and Far Western 16.0% Hills are suffering high or severe levels of food insecurity due to successive periods of drought, poor recent harvest, 15.5% insufficient supply of food in local markets and overall lack of economic opportunity. Over 50 percent of households 15.0% surveyed reported crop losses at 30-70 percent. • WFP Food for Work programming, which targeted 1.6 million 14.5% people in 2008/09, has significantly reduced the portion of Oct-Dec 08 Jan-Mar 09 Apr-Jun 09 Jul-Sep 09 Oct-Dec09 the total population which are highly and severely food Harvesting of the Summer crop and initiation of new WFP insecure. However, 145 VDCs across 12 districts of Nepal Food/Cash for Work programming have reduced the (mostly in the Mid– and Far-Western Regions but including 2 number of food insecure in the East in Sankhuwasabha) have been identified by the NeKSAP District Food Security Networks as being highly or severely food insecure. In these areas the estimated population which are unable to sustain their basic food consumption needs is 395,500. -

The Current Food Security Qtr

Nepal Food Security Bulletin Issue 25, July - October 2009 Situation Summary • The total number of food insecure people across Nepal is Figure 1. Percentage of population food insecure estimated to be 3.7 million, this represents approximately 16.4% of the rural population. WFP Nepal is feeding 1.6 17.0% million people which has had a significant impact on reducing 2009 winter drought this figure. 16.5% • July—August is typically a period of heightened food insecurity across Nepal. This year’s lean period was particularly severe in several areas of the country due to the 2008/09 winter 16.0% drought which led to reduced household food stocks and in the worst affected areas household food shortages. 15.5% • During the coming months, short term food security should continue to improve across most of Nepal as the current 15.0% harvest of summer crops (paddy, millet and maize) will be completed. However, the longer term outlook is that food security will decline within the next 6 months as summer crop 14.5% production at a national level is expected to be generally weak. Oct-Dec 09 Jan-Mar 09 Apr-Jun 09 Jul-Sep 09 Poor summer crop production is the result of late plantation (caused by late monsoon rains) combined with erratic and generally low rainfall during the monsoon. • Of the 476 households surveyed by WFP between July and September, summer crop losses of more than 30% have been experienced or are expected by more than 40% of households. Of critical concern is the situation in Bajura, Achham, Darchula, Jumla, Humla, Mugu, Dailekh, Rukum, and Taplejung where the main summer crops (paddy,millet and/or maize) have failed by 30-70% across multiple VDCs. -

Unite of Ed States F Democ

United States Agency for International Development Bureau of Democracy, Conflict and Humanitarian Assistance Office of Food for Peace Fiscal Year 2016 Quarter 1 Report (1 October 2015 – 31 December 2015) PAHAL Program Awardee Name and Host Country Mercy Corps/Nepal Award Number AID-OAA-15-00001 Project Name Promoting Agriculture, Health & Alternative Livelihoods (PAHAL) Submission Date 01/30/2016 Reporting Fiscal Yeara FY 2016 Awardee HQ Contact Name Jared Rowell, Senior Program Officer, South and Easst Asia Awardee HQ Contact Address 45 SW Ankeny St NW Portland, OR 92704 Awardee HQ Contact Telephone Number 1-503-8896-5853 Awardee HQ Contact Email Address [email protected] Host Country Office Contact Name Cary Farley, PAHAL Chief of Party Host Country Office Contact Telephone +977-1-501-2571 Number Host Country Office Contact Email Address [email protected] i Table of Contents Acronyms ..................................................................................................................................................... iii Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Annual Food Assistance Program Activities and Results ............................................................... 7 Sub-IO 1: Increased Access to Quality Health and Nutrition Services and Information ......... 7 1.1 Farmer Groups Trained on Nutritious Food Production Practices and for Household Consumption ........................................................................................................................... -

VOL.1 MINISTRYOF WORKS and TRANSPORT DEPARTMENTOF ROADS Public Disclosure Authorized

E-257 HIS MAJESTY'S GOVERNMENTOF NEPAL VOL.1 MINISTRYOF WORKS AND TRANSPORT DEPARTMENTOF ROADS Public Disclosure Authorized - t--i is £ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT Public Disclosure Authorized ASSESSMENT ROAD MAINTENANCE AND _ , DEVELOPMENTPROJECT s .~~~~~~ - -- *-=E-'''|*-.---._ Public Disclosure Authorized "SMEEC SMECInternational Pty. Ltd., Public Disclosure Authorized Cooma,NSW, Australia in associationwith CEMATConsultants (Pvt.) Ltd., Nepal April 1999 Table of Contents Project Proponent Executive Summary ii Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Project Description 1 1.3 Aims of Environmental Assessment 3 2. Legislation, Policies and Standards 5 2.1 Environmental Assessment Requirements 5 2.1.1 National Legislation 5 2.1.2 World Bank Requirements 6 2.1.3 Department of Roads Standards 7 2.2 Road Development Requirements 7 2.2.1 National Legislation 7 2.2.2 International Conventions and Treaties 9 2.2.3 National Policies 9 3. Methodology 11 3.1 EIA Scoping 11 3.2 Aligrnent Inspection 12 3.2.1 Alignment Selection 12 3.2.2 Collection of Alignment Information 13 3.3 District Interviews 14 3.4 Inspection of Existing Roads 14 3.5 Assessment of Environmental Issues 15 4. Analysis of Alternatives 20 4.1 Alternative Roads 20 4.1.1 Priority Investment Plan Project 20 4.1.2 RMD Project Screening 21 4.2 Alternative Road Alignments 28 4.3 Alignment Refinement 31 9 5. Existing Access, Proposed Alignments and Projected Traffic 33 5.1 Existing Access 33 5.1.1 Darchula Access 33 5.1.2 Martadi Access 34 5.1.3 Mangalsen Access 34 5.1.4 Jumla Access 35 5.1.5 Jajarkot Access 35 5.2 Existing Traffic Volumes 36 5.3 Proposed Alignments 6 5.4 Projected Vehicle Traffic 37 6.