KEL.112 Cover Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BTCCT-20061212AVR Communications, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CCF, et al. (Transferors) ) BTCH-20061212BYE, et al. and ) BTCH-20061212BZT, et al. Shareholders of Thomas H. Lee ) BTC-20061212BXW, et al. Equity Fund VI, L.P., ) BTCTVL-20061212CDD Bain Capital (CC) IX, L.P., ) BTCH-20061212AET, et al. and BT Triple Crown Capital ) BTC-20061212BNM, et al. Holdings III, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CDE, et al. (Transferees) ) BTCCT-20061212CEI, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212CEO For Consent to Transfers of Control of ) BTCH-20061212AVS, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212BFW, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting – Fresno, LLC ) BTC-20061212CEP, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting Operations, LLC; ) BTCH-20061212CFF, et al. AMFM Broadcasting Licenses, LLC; ) BTCH-20070619AKF AMFM Radio Licenses, LLC; ) AMFM Texas Licenses Limited Partnership; ) Bel Meade Broadcasting Company, Inc. ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; ) CC Licenses, LLC; CCB Texas Licenses, L.P.; ) Central NY News, Inc.; Citicasters Co.; ) Citicasters Licenses, L.P.; Clear Channel ) Broadcasting Licenses, Inc.; ) Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; and Jacor ) Broadcasting of Colorado, Inc. ) ) and ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BAL-20070619ABU, et al. Communications, Inc. (Assignors) ) BALH-20070619AKA, et al. and ) BALH-20070619AEY, et al. Aloha Station Trust, LLC, as Trustee ) BAL-20070619AHH, et al. (Assignee) ) BALH-20070619ACB, et al. ) BALH-20070619AIT, et al. For Consent to Assignment of Licenses of ) BALH-20070627ACN ) BALH-20070627ACO, et al. Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; ) BAL-20070906ADP CC Licenses, LLC; AMFM Radio ) BALH-20070906ADQ Licenses, LLC; Citicasters Licenses, LP; ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; and ) Clear Channel Broadcasting Licenses, Inc. ) Federal Communications Commission ERRATUM Released: January 30, 2008 By the Media Bureau: On January 24, 2008, the Commission released a Memorandum Opinion and Order(MO&O),FCC 08-3, in the above-captioned proceeding. -

Just Rewards? Local Politics and Public Resource Allocation in South India

Just Rewards? Local Politics and Public Resource Allocation in South India Timothy Besley, Rohini Pande, and Vijayendra Rao What factors determine the nature of political opportunism in local government in South India? To answer this question, we study two types of policy decisions that have been delegated to local politicians—beneficiary selection for transfer programs and the allocation of within-village public goods. Our data on village councils in South India show that, relative to other citizens, elected councillors are more likely to be selected as beneficiaries of a large transfer program. The chief councillor’s village also obtains more public goods, relative to other villages. These findings can be inter- preted using a simple model of the logic of political incentives in the context that we study. JEL codes: R51, H11, H72 Locally elected officials increasingly are responsible for the allocation of local public goods and for selecting beneficiaries for transfer programs in many low- income settings. Yet when it comes to how citizens access and use their polit- ical clout as politicians and as voters, our knowledge remains limited. In this paper, we use village and household data on resource allocation by elected village councils in South India to evaluate the nature of political opportunism in a decentralized setting. In 1993, a constitutional amendment in India instituted village-level self gov- ernment, or Gram Panchayats (GP). A typical GP comprises several villages with chief village councillor (the Pradhan) resident in one of them. The amend- ment also required political reservation of a fraction of councillor positions for historically disadvantaged groups (low castes and women). -

Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014

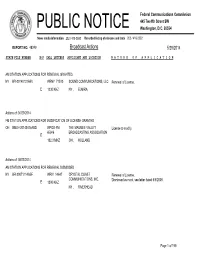

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL GRANTED NY BR-20140131ABV WENY 71510 SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Renewal of License. E 1230 KHZ NY ,ELMIRA Actions of: 04/29/2014 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR MODIFICATION OF LICENSE GRANTED OH BMLH-20140415ABD WPOS-FM THE MAUMEE VALLEY License to modify. 65946 BROADCASTING ASSOCIATION E 102.3 MHZ OH , HOLLAND Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL DISMISSED NY BR-20071114ABF WRIV 14647 CRYSTAL COAST Renewal of License. COMMUNICATIONS, INC. Dismissed as moot, see letter dated 5/5/2008. E 1390 KHZ NY , RIVERHEAD Page 1 of 199 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED NY BAL-20140212AEC WGGO 9409 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License From: PEMBROOK PINES, INC. E 1590 KHZ NY , SALAMANCA To: SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Form 314 NY BAL-20140212AEE WOEN 19708 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. -

MMR 24-7 Song Airplay Detail 5/27/14, 11:45 AM

MMR 24-7 Song Airplay Detail 5/27/14, 11:45 AM 7 Day NICO & VINZ Please set all print margins to 0.50 Song Analysis Am I Wrong Warner Bros. Mediabase - All Stations (U.S.) - by Format LW: May 13 - May 19 TW: May 20 - May 26 Updated: Tue May 27 3:17 AM PST N Sng Rnk Spins Station (Click Graphic for Mkt e @Station Market Format Trade TW lw +/- -1 -2 -3 -4 -5 -6 -7to Airplay Trends) Rank w (currents) Date KDWB-FM * 1 16 Minneapolis Top 40 Mediabase 114 70 44 19 15 13 16 17 16 18 453 WZEE-FM * 5 99 Madison, WI Top 40 Mediabase 80 36 44 13 9 11 13 10 13 11 264 WXXL-FM * 3 33 Orlando Top 40 Mediabase 78 73 5 12 8 9 12 12 13 12 326 WKCI-FM * 5 121 New Haven, CT Top 40 Mediabase 77 40 37 14 8 8 12 13 15 7 292 WFBC-FM * 8 59 Greenville, SC Top 40 Mediabase 73 69 4 10 10 11 10 11 10 11 367 WNOU-FM * 10 40 Indianapolis Top 40 Mediabase 73 63 10 9 10 9 11 12 10 12 319 WVHT-FM * 9 43 Norfolk Top 40 Mediabase 71 34 37 10 9 9 10 11 11 11 199 WKXJ-FM * 6 107 Chattanooga Top 40 Mediabase 69 40 29 13 6 6 14 12 12 6 210 KMVQ-FM * 6 4 San Francisco Top 40 Mediabase 67 68 -1 10 8 7 11 11 10 10 384 KFRH-FM * 11 32 Las Vegas Top 40 Mediabase 67 65 2 9 8 10 9 10 11 10 420 WXZO-FM * 13 143 Burlington, VT Top 40 Mediabase 66 44 22 11 7 8 10 11 11 8 228 KBFF-FM * 5 23 Portland, OR Top 40 Mediabase 65 72 -7 7 8 7 10 12 10 11 327 KREV-FM 9 4 San Francisco Top 40 Mediabase 65 60 5 9 9 12 9 9 9 8 192 WDJX-FM * 5 54 Louisville Top 40 Mediabase 64 61 3 10 9 10 10 8 9 8 318 WKSC-FM * 10 3 Chicago Top 40 Mediabase 63 38 25 10 7 9 9 10 9 9 200 WJHM-FM * 10 33 Orlando Top -

The New Nuclear Weapons by John Laforge John Reed and the Russian

The new nuclear weapons by john laforge john reed and The russian revoluTion by p. sainaTh The presidenT and The porn sTar by ruTh fowler mexico’s big elecTions by kenT paTerson The fbi aT work by paul krassner TELLS THE FACTS AND NAMES THE NAMES · VOLUME 25 NUMBER 2 2018 AND NAMES THE · VOLUME THE FACTS TELLS editorial: 1- year digital edition (PDF) $25 [email protected] 1- year institutions/supporters $100 www.counterpunch.org business: [email protected] 1- year print/digital for student/low CounterPunch Magazine, Volume 25, subscriptions and merchandise: income $40 (ISSN 1086-2323) is a journal of progres- [email protected] 1-year digital for student/low income $20 sive politics, investigative reporting, civil All subscription orders must be prepaid— liberties, art, and culture published by The Submissions we do not invoice for orders. Renew by Institute for the Advancment of Journalis- CounterPunch accepts a small number of telephone, mail, or on our website. For tic Clarity, Petrolia, California, 95558.Visit submissions from accomplished authors mailed orders please include name, ad- counterpunch.org to read dozens of new and newer writers. Please send your pitch dress and email address with payment, or articles daily, purchase subscriptions, or- to [email protected]. Due call 1 (800) 840-3683 or 1 (707) 629-3683. der books and access 18 years of archives. to the large volume of submissions we re- Add $25.00 per year for subscriptions Periodicals postage pending ceive we are able to respond to only those mailed to Canada and $45 per year for all at Eureka, California. -

Buffy & Angel Watching Order

Start with: End with: BtVS 11 Welcome to the Hellmouth Angel 41 Deep Down BtVS 11 The Harvest Angel 41 Ground State BtVS 11 Witch Angel 41 The House Always Wins BtVS 11 Teacher's Pet Angel 41 Slouching Toward Bethlehem BtVS 12 Never Kill a Boy on the First Date Angel 42 Supersymmetry BtVS 12 The Pack Angel 42 Spin the Bottle BtVS 12 Angel Angel 42 Apocalypse, Nowish BtVS 12 I, Robot... You, Jane Angel 42 Habeas Corpses BtVS 13 The Puppet Show Angel 43 Long Day's Journey BtVS 13 Nightmares Angel 43 Awakening BtVS 13 Out of Mind, Out of Sight Angel 43 Soulless BtVS 13 Prophecy Girl Angel 44 Calvary Angel 44 Salvage BtVS 21 When She Was Bad Angel 44 Release BtVS 21 Some Assembly Required Angel 44 Orpheus BtVS 21 School Hard Angel 45 Players BtVS 21 Inca Mummy Girl Angel 45 Inside Out BtVS 22 Reptile Boy Angel 45 Shiny Happy People BtVS 22 Halloween Angel 45 The Magic Bullet BtVS 22 Lie to Me Angel 46 Sacrifice BtVS 22 The Dark Age Angel 46 Peace Out BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part One Angel 46 Home BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part Two BtVS 23 Ted BtVS 71 Lessons BtVS 23 Bad Eggs BtVS 71 Beneath You BtVS 24 Surprise BtVS 71 Same Time, Same Place BtVS 24 Innocence BtVS 71 Help BtVS 24 Phases BtVS 72 Selfless BtVS 24 Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered BtVS 72 Him BtVS 25 Passion BtVS 72 Conversations with Dead People BtVS 25 Killed by Death BtVS 72 Sleeper BtVS 25 I Only Have Eyes for You BtVS 73 Never Leave Me BtVS 25 Go Fish BtVS 73 Bring on the Night BtVS 26 Becoming, Part One BtVS 73 Showtime BtVS 26 Becoming, Part Two BtVS 74 Potential BtVS 74 -

Farm Bureau News October 2013 Bytes

Farm Bureau News October 2013 bytes WVU Extension Sponsors General Motors Announces Added Discount for Farm Oil & Gas Drilling Bureau Members Only Educational Programs Effective immediately, and You must be a Farm Bureau West Virginia is home of one of continuing through April 1, 2014, member for at least 60 days to take the largest Marcellus Shale natural Chevrolet and GMC are offering advantage of this offer, and the gas deposits on the East Coast. exclusively to Farm Bureau address on your drivers license must As landowners and community members an additional $1,000 match your home mailing address. members began asking questions incentive on the purchase of any new Every member of your household of WVU Extension agents about 2013 or 2014 regular cab heavy duty can take advantage of this offer! this topic, they organized a series (2500/3500) And remember of workshops to help the public series truck. to remind learn about aspects of the oil and This is in dealers of your gas industry and how it could affect addition to the Farm Bureau them. standard $500 membership Farm Bureau so that you can “Gas Well Drilling and Your incentive - take advantage Private Water Supply” will be for a total of of all the presented on November 18, 6:00 $1500! This incentives you p.m., at the Winfield Community private offer is are eligible for! Building, Fairmont, WV; and also stackable November 19, 6:00 p.m., at the with all retail Can’t access Doddridge County Park Building, promotions - the website? West Union, WV. -

2021 Iheartradio Music Festival Win Before You Can Buy Flyaway Sweepstakes Appendix a - Participating Stations

2021 iHeartRadio Music Festival Win Before You Can Buy Flyaway Sweepstakes Appendix A - Participating Stations Station Market Station Website Office Phone Mailing Address WHLO-AM Akron, OH 640whlo.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WHOF-FM Akron, OH sunny1017.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WHOF-HD2 Akron, OH cantonsnewcountry.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WKDD-FM Akron, OH wkdd.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WRQK-FM Akron, OH wrqk.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WGY-AM Albany, NY wgy.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WGY-FM Albany, NY wgy.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WKKF-FM Albany, NY kiss1023.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WOFX-AM Albany, NY foxsports980.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WPYX-FM Albany, NY pyx106.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WRVE-FM Albany, NY 995theriver.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WRVE-HD2 Albany, NY wildcountry999.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WTRY-FM Albany, NY 983try.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 KABQ-AM Albuquerque, NM abqtalk.iheart.com 505-830-6400 5411 Jefferson NE, Ste 100, Albuquerque, NM 87109 KABQ-FM Albuquerque, NM hotabq.iheart.com 505-830-6400 -

Sojourner Adjustment : a Diary Study

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1992 Sojourner Adjustment : A Diary Study Susan Elizabeth Hemstreet Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Applied Linguistics Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hemstreet, Susan Elizabeth, "Sojourner Adjustment : A Diary Study" (1992). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4377. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6261 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Susan Elizabeth Hemstreet for the Master of Arts in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages presented January 21, 1992. Title: Sojourner Adjustment: A Diary Study. APPROVED BY THE MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: Maqone ~. Terdal, Chair Suwako Watanabe The focus of the ethnographic diary study is introduced and contextualized in the opening chapter with a site description. The thesis examines the diaries written during a sojourn of over two years in Japan . and proposes to answer the question, "How did the sojourner's initial maladjustment subsequently develop into satisfactory adjustment?" 2 The literature on diary studies, culture shock and sojourner adjustment is reviewed in order to establish standards of the diary study genre and a framework from which to analyze the diary. Using the qualitative methods of a diary study, salient themes of the adjustment are examined. The diarist's progression through the adjustment stages as proposed by the literature is supported, and the coping strategies of escapism, reaching out to people, writing, positive thinking, religious beliefs, compulsive behaviors, goal-setting and seeing the experience as finite are discussed in depth. -

UPOA-Volume-94.Pdf

Utah Peace Officers Association Board of Directors UPOA BOARD OF DIRECTORS Rev. 1-3-18 PRESIDENT/PUB. SAFETY REGION B REPRESENTATIVE REGION J REPRESENTATIVE RETIREMENT Vacant Cory Norman, SCI PD Arlow Hancock, UHP, Cache Co. SO 435-705-0795 801-381-5417 [email protected] [email protected] PRESIDENT ELECT REGION B REPRESENTATIVE REGION K REPRESENTATIVE Arlow Hancock, UHP, Cache Co. SO Merv Taylor, Weber State Univ. PD Jeff Jones, UHP 801-381-5417 801-549-7434 435-743-6530 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] VICE PRESIDENT REGION C REPRESENTATIVE UTAH ALARM SYS SEC. LIC. BD Damon Orr, San Juan County SO Phil Kirk, Park City PD Larry Gillett, Retired/Corrections 435-979-2116 435-615-5512 801-968-9797 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT REGION C REPRESENTATIVE ULELC - LEGISLATIVE CHAIR Eric Whitehead, Lindon PD Domonic Adamson, Pleasant Grv PD Brian Locke, Cache County SO 801-769-8600 801-404-1514 435-755-1280 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] SECRETARY REGION C REPRESENTATIVE PISTOL CHAIR Mike Galieti, Retired PD Kirk Folsom, Lehi PD Greg Severson, Sandy PD 801-707-8610 801-768-7110 801-568-7237 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] TREASURER & ADMIN. ASST. REGION D REPRESENTATIVE MULTI GUN CHAIR Kent Curtis, Retired U of U PD Skyler Jensen, Cache County SO Jeremy Dunn, Enoch PD 801-560-7367 435-754-4798 435-704-4344 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] SERGEANT AT ARMS REGION E REPRESENTATIVE K -9 TRIALS CHAIR Shalon Shaver, Iron County SO Jeremy Dunn, Enoch PD Rose Cox, Retired SLC PD 435-867-7555 435-704-4344 385-229-0742 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] LEGAL COUNSEL REGION F REPRESENTATIVE CORRECTIONS REP. -

Chronology of Women in the West Virginia Legislature

Chronology Wof men in the West Virginia Legislature 1922-2020 West Virginia Legislature’s Office of Reference & Information, Joint Committee on Government & Finance. 2019. Chronology of Women IN THE West Virginia Legislature When the first woman was elected to office in the mountain state in 1922, West Virginia couldn’t have prepared for the unstoppable force that would become the female politicians the state has to offer. Since Mrs. Anna Gates’s election as a Delegate in 1922, hundreds of empowered women from all over the state have won elections and held a seat in the statehouse, where they helped to craft the policies that have shaped West Virginia for decades. Without the courage and stamina of these women to challenge the men who occupied these seats and hold their own on the chamber floors, West Virginia would look drastically different today. This extensive Chronology of Women in the West Virginia Legislature helps to commemorate the legacies of the hard-working and powerful women who overcame societal expectations to make a difference in the state that they loved and called home. Revised NOVEMBER 2019 7 Delegates 1920s (4 elected, 3 appointed) Delegates 1922 - 1 Delegate (elected) Mrs. Tom (Anna) Gates (D) Kanawha, elected (First woman elected to the West Virginia Legislature.) 1924 - 2 Delegates (both elected) Mrs. Thomas J. Davis (R) Fayette, elected 192 Dr. Harriet B. Jones (R) Marshall, elected 0s 1926 - 2 Delegates (both appointed) Hannah Cooke (D) Jefferson (Appointed Jan. 27 by Gov. Howard Mason Gore upon the death of her husband.) Mrs. Fannie Anshutz Hall (D) Wetzel (Appointed Apr. -

Chronology of Women in the West Virginia Legislature Revised July 30, 2009 7 Delegates 0 Senators 1920S (4 Elected, 3 Appointed)

Chronology Wof men in the West Virginia Legislature 1922-2009 West Virginia Legislature’s Office of Reference & Information, Joint Committee on Government & Finance - January 2009 The Chronology of Women in the West Virginia Legislature Revised July 30, 2009 7 Delegates 0 Senators 1920s (4 elected, 3 appointed) Delegates 1922 - 1 Delegate (elected) Mrs. Tom (Anna) Gates (D) Kanawha, elected (first woman elected to the West Virginia Legislature) 1924 - 2 Delegates (both elected) Mrs. Thomas J. Davis (R) Fayette, elected Dr. Harriet B. Jones (R) Marshall, elected 1920s1926 - 2 Delegates (both appointed) Hannah Cooke (D) Jefferson (Appointed Jan. 27 by Gov. Howard Mason Gore upon the death of her husband.) Mrs. Fannie Anshutz Hall (D) Wetzel (Appointed Apr. 2 by Gov. Gore upon the death of her husband.) 1928 - 2 Delegates (1 elected, 1 appointed) Mrs. Minnie Buckingham Harper (R) McDowell (Appointed Jan. 10 by Gov. Gore upon the death of her husband.) Frances Irving Radenbaugh (R) Wood, elected 7 Delegates 2 Senators 1930s (4 elected, 3 appointed) (both appointed) Senators 1934 - 1 Senator (appointed) Mrs. Hazel E. Hyre (D) Jackson (Appointed Mar. 12 by Gov. Herman Guy Kump upon the death of her husband.) 1939 - Mrs. John C. Dice (D) Greenbrier (Appointed in Dec. by Gov. Homer Holt upon the death of Sen. William Jasper.) 1930sDelegates 1931 - Mrs. Lucille Scott Strite (D) Morgan (Appointed by Gov. William Conley upon the death of James C. Scott.) 1932 - 2 Delegates (both elected) Mrs. Pearl Theressa Harman (R) McDowell, elected Eddie Seiver Suddarth (D) Taylor, elected 1934 - 1 Delegate (elected) Mrs. S.W.