Authenticity and Practicality: Evaluating and Performing Multicultural Choral Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celebrate Hispanic Heritage Month! for People Who Love Books And

Calendar of Events September 2016 For People Who Love Books and Enjoy Experiences That Bring Books to Life. “This journey has always been about reaching your own other shore, no matter what it is, and that dream continues.” Diana Nyad The Palm Beach County Library System is proud to present the third annual Book Life series, a month of activities and experiences designed for those who love to read. This year, Celebrate Hispanic we have selected two books exploring journeys; the literal and figurative, the personal and shared, and their power to define Heritage Month! or redefine all who proceed along the various emerging paths. The featured books for Book Life 2016 are: By: Maribel de Jesús • “Carrying Albert Home: The Somewhat True Story Multicultural Outreach Services Librarian of a Man, His Wife, and Her Alligator,” by Homer For the eleventh consecutive year the Palm Beach County Library System Hickham celebrates our community’s cultural diversity, the beautiful traditions of • “Find a Way,” by Diana Nyad Latin American countries, and the important contributions Hispanics have Discover the reading selections and enjoy a total of 11 made to American society. educational, engaging experiences inspired by the books. The national commemoration of Hispanic Heritage Month began with a Activities, events and book discussions will be held at various week-long observance, started in 1968 by President Lyndon B. Johnson. library branches and community locations throughout the Twenty years later, President Ronald Reagan expanded the observation month of September. to September 15 - October 15, a month-long period which includes several This series is made possible through the generous support of Latin American countries’ anniversaries of independence. -

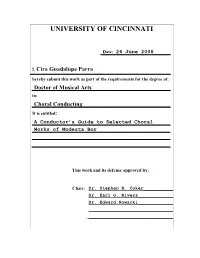

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 26 June 2006 I, Cira Guadalupe Parra hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in: Choral Conducting It is entitled: A Conductor’s Guide to Selected Choral Works of Modesta Bor This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Dr. Stephen R. Coker___________ Dr. Earl G. Rivers_____________ Dr. Edward Nowacki_____________ _______________________________ _______________________________ A Conductor’s Guide to Selected Choral Works of Modesta Bor A document submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Ensembles and Conducting Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2006 by Cira Parra 620 Clinton Springs Ave Cincinnati, Ohio 45229 [email protected] B.M., University of Cincinnati, College-Conservatory of Music, 1987 M.M., University of Cincinnati, College-Conservatory of Music, 1989 Committee Chair: Stephen R. Coker ABSTRACT Modesta Bor (1926-98) was one of the outstanding Venezuelan composers, conductors, music educators and musicologists of the twentieth century. She wrote music for orchestra, chamber music, piano solo, piano and voice, and incidental music. She also wrote more than 95 choral works for mixed voices and 130 for equal-voice choir. Her style is a mixture of Venezuelan nationalism and folklore with European traits she learned in her studies in Russia. Chapter One contains a historical background of the evolution of Venezuelan art music since the colonial period, beginning in 1770. Knowing the state of art music in Venezuela helps one to understand the unusual nature of the Venezuelan choral movement that developed in the first half of the twentieth century. -

Gene Pitney, 1940-2006

10 Grapevine GRAPELEAVES Gene Pitney, 1940-2006 Singer/songwriter and News & notes: The James Gang rides Yoakam and others... There are two new Rock And Roll Hall Of again! For the first time in 35 years James titles in Music Video Distributors’ Under Fame member (2002), Gang members Joe Walsh, Jim Fox, and Review series, Velvet Underground, Gene Francis Allan Dale Peters will tour together. The first Under Review and Captain Beefheart, Pitney, age 66, died show kicks off Aug. 9 at Colorado’s Red Under Review. Each DVD features rare unexpectedly of natural Rocks Amphitheatre. Complete tour date performances and interviews along with causes in his Hilton info is available at jamesgang commentary and criticism from band Hotel room April 5, ridesagain.com... This spring will find members and music writers... Other 2006, in Cardiff, Wales. another band on the road for the first time recent DVD releases include Judas He was midway through in many years. Seattle’s Alice In Chains Priest, Live Vengeance ’82. This 17-song www.goldminemag.com GOLDMINE #673 May 12, 2006 • GOLDMINE #673 May www.goldminemag.com a 23-city United members Jerry Cantrell, Mike Inez, and set features the band’s 1982 Memphis, Kingdom tour; he had Sean Kinney haven’t toured together as a Tenn., show ripping out fan faves such just played Cardiff’s St. band since 1996. A re-linked Chains will as “The Hellion/Electric Eye,” “Heading David’s Hall and was hit the stage May 26 at Lisbon, Portugal’s Out To The Highway” and “Hell Bent scheduled to perform Super Bock Festival. -

SLS 19RS-33 ORIGINAL 2019 Regular Session SENATE

SLS 19RS-33 ORIGINAL 2019 Regular Session SENATE CONCURRENT RESOLUTION NO. 132 BY SENATOR PEACOCK COMMENDATIONS. Commends music legend James Burton of Shreveport, on the occasion of his eightieth birthday. 1 A CONCURRENT RESOLUTION 2 To commend James Burton for an outstanding career of over sixty years as a performer, 3 musician, and a Louisiana music legend and to congratulate him on the occasion of 4 his eightieth birthday. 5 WHEREAS, born in Dubberly, Louisiana, on August 21, 1939, James Edward Burton 6 grew up in Shreveport; he received his first guitar as a youngster and was playing 7 professionally by the age of fourteen; he was a self-taught musical phenomenon; and 8 WHEREAS, as he listened to KWKH radio, he was influenced by popular guitarists 9 of the day, such as Chet Atkins, Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, Elmore James, Lightnin' Hopkins 10 and many others whose genres covered Rock and Roll, Delta Blues, and Country music; and 11 WHEREAS, James was required to obtain a special permit to play in nightclubs due 12 to his age, however, his guitar playing showed such promise that he was asked to join the 13 "staff band" of the legendary radio show, the Louisiana Hayride, and he played backup for 14 the likes of George Jones, Billy Walker, and Johnny Horton and within a few years, James 15 would be a headliner at the show; and 16 WHEREAS, he honed his craft on a variety of guitar types that included acoustic, 17 steel guitar, slide dobro, and electric styles like Fender Telecasters; no matter who played 18 lead guitar, James Burton had the guitar "licks" to complement the lead note for note; and Page 1 of 3 SLS 19RS-33 ORIGINAL SCR NO. -

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

SHOEMAKER, ANN H., DMA the Pedagogy of Becoming

SHOEMAKER, ANN H., D.M.A. The Pedagogy of Becoming: Identity Formation through the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra’s OrchKids and Venezuela’s El Sistema. (2012) Directed by Drs. Michael Burns and Gavin Douglas. 153 pp. Rapid development of El Sistema-inspired music programs around the world has left many music educators seeking the tools to emulate El Sistema effectively. This paper offers information to these people by evaluating one successful program in the United States and how it reflects the intent and mission of El Sistema. Preliminary research on El Sistema draws from articles and from information provided by Mark Churchill, Dean Emeritus of New England Conservatory’s Department of Preparatory and Continuing Education and director of El Sistema USA. Travel to Baltimore, Maryland and to four cities in Venezuela allowed for observation and interviews with people from the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra’s OrchKids program and four núcleos in El Sistema, respectively. OrchKids and El Sistema aim to improve the lives of their students and their communities, but El Sistema takes action only through music while OrchKids has a broader spectrum of activities. OrchKids also uses a wider variety of musical genres than El Sistema does. Both programs impact their students by giving them a strong sense of personal identity and of belonging to community. The children learn responsibility to the communities around them such as their neighborhood and their orchestra, and also develop a sense of belonging to a larger international music community. THE PEDAGOGY OF BECOMING: IDENTITY FORMATION THROUGH THE BALTIMORE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA’S ORCHKIDS AND VENEZUELA’S EL SISTEMA by Ann H. -

CAROLS for CHRISTMAS Carols and Seasonal Readings for Christmas and Winter

Gerald Neufeld conductor Alison MacNeill accompanist CAROLS FOR CHRISTMAS Carols and Seasonal Readings for Christmas and Winter Sunday November 30, 2014 WINTER’S EVE TRIO St. George’s Anglican Church | 3:00 pm Sharlene Wallace Harp Joe Macerollo Accordion George Koller Bass concert sponsors soloist sponsors government & community support Program CAROLS FOR CHRISTMAS Carols and Seasonal Readings for Christmas and Winter Hodie . Gregorian Chant Wolcum Yole, from Ceremony of Carols . Benjamin Britten Herself a rose, who bore the Rose . Christina Rossetti Laurie McDonald, reader As dew in Aprille, from Ceremony of Carols . Benjamin Britten Birth of Jesus . Luke 2, 1–20 Scott Worsfold, reader This little Babe, from Ceremony of Carols . Benjamin Britten Interlude, from Ceremony of Carols . Benjamin Britten Greensleeves . .. Traditional Winter’s Eve Trio What Child is this . arr . John Stainer Winter’s Eve Trio, choir and audience 1. What child is this, who laid to rest 2. Why lies He in such mean estate, On Mary’s lap is sleeping? Where ox and ass are feeding? Whom angels greet with anthem sweet, Good Christian, fear: for sinners here While shepherds watch are keeping? The silent Word is pleading; This, this is Christ, the King; Nails, spear shall pierce Him through, Whom shepherds guard and angels sing; The Cross be born for me, for you; Haste, haste to bring Him laud, Hail, hail the Word made flesh, The Babe, the Son of Mary! The Babe, the Son of Mary! 3. So bring Him incense, gold, and myrrh, Come peasant, king to own Him; The King of kings salvation brings; Let loving hearts enthrone Him. -

Alan Lomax: Selected Writings 1934-1997

ALAN LOMAX ALAN LOMAX SELECTED WRITINGS 1934–1997 Edited by Ronald D.Cohen With Introductory Essays by Gage Averill, Matthew Barton, Ronald D.Cohen, Ed Kahn, and Andrew L.Kaye ROUTLEDGE NEW YORK • LONDON Published in 2003 by Routledge 29 West 35th Street New York, NY 10001 www.routledge-ny.com Published in Great Britain by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane London EC4P 4EE www.routledge.co.uk Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group. This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” All writings and photographs by Alan Lomax are copyright © 2003 by Alan Lomax estate. The material on “Sources and Permissions” on pp. 350–51 constitutes a continuation of this copyright page. All of the writings by Alan Lomax in this book are reprinted as they originally appeared, without emendation, except for small changes to regularize spelling. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lomax, Alan, 1915–2002 [Selections] Alan Lomax : selected writings, 1934–1997 /edited by Ronald D.Cohen; with introductory essays by Gage Averill, Matthew Barton, Ronald D.Cohen, Ed Kahn, and Andrew Kaye. -

Steve Sachse 2018

Copyright by Stephen Michael Sachse 2018 Root Motion: For Chamber Ensemble With Electronics by Stephen Michael Sachse Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2018 Acknowledgments I would like to express my most sincere appreciation to the entire composition faculty of the University of Texas at Austin: Russell Pinkston, Yevgeniy Sharlat, Bruce Pennycook, Donald Grantham, and Dan Welcher. I have needed every bit of help and knowledge you have provided along the way in staying on my feet and finding my path forward as an artist. You were there for me when I needed you the most, and I will forever be grateful to all of you for that. I would also like to thank my closest friends in the department who have also stuck by my side and encouraged me every step of the way: Eli, Jon, José, Kramer, Chris and Chris, Josh, Robert, Corey, Lauren, and Michael. I also want to extend my most heartfelt thanks to Dr. Russell Pinkston. With the utmost sincerity and respect I would like to congratulate you on your career as an educator, researcher, and leader within the fields of composition and electronic music. I can say beyond any shadow of doubt that you have been the most influential teacher in my life, and have been one of my most deeply respected friends and allies. Each one of us greatly appreciated the way that you organized the electronic music program and its concerts, cared for the studios, handled the electronic music forum, and the way that you have led by example. -

Harp Seattle 2018 Booklet WEB ONLY.Pub

General Information for HARP SEATTLE 2018 About Harp Seattle Rental Harps Harp Seattle is a three-day festival at Dusty Strings Music Once you register, you can indicate on your registration Store & School in Seattle, WA for harpers of all levels to form if you would like to rent a harp, and if so, what kind. participate in an event that has been part of the folk harp We will contact you a month before the event to set up community for over a decade. Seasoned performers pre- your rental. Availability is first-come-first-served. sent workshops created to enhance the skills and knowledge of players at all levels so there’s something for everyone. Refund Policy You may cancel your registration for a full refund less a Location $25 administrative fee through September 5 th , 2018. You All workshops, concerts, and happenings take place at may cancel your registration for a 50% refund less a $25 Dusty Strings Music Store & School, 3406 Fremont Avenue administrative fee through October 1 st , 2016. No refunds N, Seattle, except for the tour of the manufacturing facility, are available for partial attendance or for cancellations which is located at 3450 16 th Avenue W in the Interbay made after October 1 st . All workshops, presenters, and neighborhood. See page 12 for directions and parking times are subject to change. information for both locations. Harp Valet Registration Harp valets are ready to assist you with dropping off your Registration includes an all-access pass to the weekend’s harp on Friday morning, October 5 th and picking it up on workshops, concerts, and happenings. -

Concert & Dance Listings • Cd Reviews • Free Events

CONCERT & DANCE LISTINGS • CD REVIEWS • FREE EVENTS FREE BI-MONTHLY Volume 4 Number 6 Nov-Dec 2004 THESOURCE FOR FOLK/TRADITIONAL MUSIC, DANCE, STORYTELLING & OTHER RELATED FOLK ARTS IN THE GREATER LOS ANGELES AREA “Don’t you know that Folk Music is illegal in Los Angeles?” — WARREN C ASEY of the Wicked Tinkers Music and Poetry Quench the Thirst of Our Soul FESTIVAL IN THE DESERT BY ENRICO DEL ZOTTO usic and poetry rarely cross paths with war. For desert dwellers, poetry has long been another way of making war, just as their sword dances are a choreographic represen- M tation of real conflict. Just as the mastery of insideinside thisthis issue:issue: space and territory has always depended on the control of wells and water resources, words have been constantly fed and nourished with metaphors SomeThe Thoughts Cradle onof and elegies. It’s as if life in this desolate immensity forces you to quench two thirsts rather than one; that of the body and that KoreanCante Folk Flamenco Music of the soul. The Annual Festival in the Desert quenches our thirst of the spirit…Francis Dordor The Los Angeles The annual Festival in the Desert has been held on the edge Put On Your of the Sahara in Mali since January 2001. Based on the tradi- tional gatherings of the Touareg (or Tuareg) people of Mali, KlezmerDancing SceneShoes this 3-day event brings together participants from not only the Tuareg tradition, but from throughout Africa and the world. Past performers have included Habib Koité, Manu Chao, Robert Plant, Ali Farka Toure, and Blackfire, a Navajo band PLUS:PLUS: from Arizona. -

Download the File “Tackforalltmariebytdr.Pdf”

Käraste Micke med barn, Tillsammans med er sörjer vi en underbar persons hädangång, och medan ni har förlorat en hustru och en mamma har miljoner av beundrare världen över förlorat en vän och en inspirationskälla. Många av dessa kände att de hade velat prata med er, dela sina historier om Marie med er, om vad hon betydde för dem, och hur mycket hon har förändrat deras liv. Det ni håller i era händer är en samling av över 6200 berättelser, funderingar och minnen från människor ni förmodligen inte kän- ner personligen, men som Marie har gjort ett enormt intryck på. Ni kommer att hitta både sorgliga och glada inlägg förstås, men huvuddelen av dem visar faktiskt hur enormt mycket bättre världen har blivit med hjälp av er, och vår, Marie. Hon kommer att leva kvar i så många människors hjärtan, och hon kommer aldrig att glömmas. Tack för allt Marie, The Daily Roxette å tusentals beundrares vägnar. A A. Sarper Erokay from Ankara/ Türkiye: How beautiful your heart was, how beautiful your songs were. It is beyond the words to describe my sorrow, yet it was pleasant to share life on world with you in the same time frame. Many of Roxette songs inspired me through life, so many memories both sad and pleasant. May angels brighten your way through joining the universe, rest in peace. Roxette music will echo forever wihtin the hearts, world and in eternity. And you’ll be remembered! A.Frank from Germany: Liebe Marie, dein Tod hat mich zu tiefst traurig gemacht. Ich werde deine Musik immer wieder hören.