Study of Behavior: Science Or Pseudoscience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jackson: Choosing a Methodology: Philosophical Underpinning

JACKSON: CHOOSING A METHODOLOGY: PHILOSOPHICAL UNDERPINNING Choosing a Methodology: Philosophical Practitioner Research Underpinning In Higher Education Copyright © 2013 University of Cumbria Vol 7 (1) pages 49-62 Elizabeth Jackson University of Cumbria [email protected] Abstract As a university lecturer, I find that a frequent question raised by Masters students concerns the methodology chosen for research and the rationale required in dissertations. This paper unpicks some of the philosophical coherence that can inform choices to be made regarding methodology and a well-thought out rationale that can add to the rigour of a research project. It considers the conceptual framework for research including the ontological and epistemological perspectives that are pertinent in choosing a methodology and subsequently the methods to be used. The discussion is exemplified using a concrete example of a research project in order to contextualise theory within practice. Key words Ontology; epistemology; positionality; relationality; methodology; method. Introduction This paper arises from work with students writing Masters dissertations who frequently express confusion and doubt about how appropriate methodology is chosen for research. It will be argued here that consideration of philosophical underpinning can be crucial for both shaping research design and for explaining approaches taken in order to support credibility of research outcomes. It is beneficial, within the unique context of the research, for the researcher to carefully -

The Rhetoric of Positivism Versus Interpretivism: a Personal View1

Weber/Editor’s Comments EDITOR’S COMMENTS The Rhetoric of Positivism Versus Interpretivism: A Personal View1 Many years ago I attended a conference on interpretive research in information systems. My goal was to learn more about interpretive research. In my Ph.D. education, I had studied primarily positivist research methods—for example, experiments, surveys, and field studies. I knew little, however, about interpretive methods. I hoped to improve my knowledge of interpretive methods with a view to using them in due course in my research work. A plenary session at the conference was devoted to a panel discussion on improving the acceptance of interpretive methods within the information systems discipline. During the session, a number of speakers criticized positivist research harshly. Many members in the audience also took up the cudgel to denigrate positivist research. If any other positivistic researchers were present at the session beside me, like me they were cowed. None of us dared to rise and speak in defence of positivism. Subsequently, I came to understand better the feelings of frustration and disaffection that many early interpretive researchers in the information systems discipline experienced when they attempted to publish their work. They felt that often their research was evaluated improperly and treated unfairly. They contended that colleagues who lacked knowledge of interpretive research methods controlled most of the journals. As a result, their work was evaluated using criteria attuned to positivism rather than interpretivism. My most-vivid memory of the panel session, however, was my surprise at the way positivism was being characterized by my colleagues in the session. -

A Comprehensive Framework to Reinforce Evidence Synthesis Features in Cloud-Based Systematic Review Tools

applied sciences Article A Comprehensive Framework to Reinforce Evidence Synthesis Features in Cloud-Based Systematic Review Tools Tatiana Person 1,* , Iván Ruiz-Rube 1 , José Miguel Mota 1 , Manuel Jesús Cobo 1 , Alexey Tselykh 2 and Juan Manuel Dodero 1 1 Department of Informatics Engineering, University of Cadiz, 11519 Puerto Real, Spain; [email protected] (I.R.-R.); [email protected] (J.M.M.); [email protected] (M.J.C.); [email protected] (J.M.D.) 2 Department of Information and Analytical Security Systems, Institute of Computer Technologies and Information Security, Southern Federal University, 347922 Taganrog, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Systematic reviews are powerful methods used to determine the state-of-the-art in a given field from existing studies and literature. They are critical but time-consuming in research and decision making for various disciplines. When conducting a review, a large volume of data is usually generated from relevant studies. Computer-based tools are often used to manage such data and to support the systematic review process. This paper describes a comprehensive analysis to gather the required features of a systematic review tool, in order to support the complete evidence synthesis process. We propose a framework, elaborated by consulting experts in different knowledge areas, to evaluate significant features and thus reinforce existing tool capabilities. The framework will be used to enhance the currently available functionality of CloudSERA, a cloud-based systematic review Citation: Person, T.; Ruiz-Rube, I.; Mota, J.M.; Cobo, M.J.; Tselykh, A.; tool focused on Computer Science, to implement evidence-based systematic review processes in Dodero, J.M. -

PDF Download Starting with Science Strategies for Introducing Young Children to Inquiry 1St Edition Ebook

STARTING WITH SCIENCE STRATEGIES FOR INTRODUCING YOUNG CHILDREN TO INQUIRY 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Marcia Talhelm Edson | 9781571108074 | | | | | Starting with Science Strategies for Introducing Young Children to Inquiry 1st edition PDF Book The presentation of the material is as good as the material utilizing star trek analogies, ancient wisdom and literature and so much more. Using Multivariate Statistics. Michael Gramling examines the impact of policy on practice in early childhood education. Part of a series on. Schauble and colleagues , for example, found that fifth grade students designed better experiments after instruction about the purpose of experimentation. For example, some suggest that learning about NoS enables children to understand the tentative and developmental NoS and science as a human activity, which makes science more interesting for children to learn Abd-El-Khalick a ; Driver et al. Research on teaching and learning of nature of science. The authors begin with theory in a cultural context as a foundation. What makes professional development effective? Frequently, the term NoS is utilised when considering matters about science. This book is a documentary account of a young intern who worked in the Reggio system in Italy and how she brought this pedagogy home to her school in St. Taking Science to School answers such questions as:. The content of the inquiries in science in the professional development programme was based on the different strands of the primary science curriculum, namely Living Things, Energy and Forces, Materials and Environmental Awareness and Care DES Exit interview. Begin to address the necessity of understanding other usually peer positions before they can discuss or comment on those positions. -

Principles of Scientific Inquiry

Chapter 2 PRINCIPLES OF SCIENTIFIC INQUIRY Introduction This chapter provides a summary of the principles of scientific inquiry. The purpose is to explain terminology, and introduce concepts, which are explained more completely in later chapters. Much of the content has been based on explanations and examples given by Wilson (1). The Scientific Method Although most of us have heard, at some time in our careers, that research must be carried out according to “the scientific method”, there is no single, scientific method. The term is usually used to mean a systematic approach to solving a problem in science. Three types of investigation, or method, can be recognized: · The Observational Method · The Experimental (and quasi-experimental) Methods, and · The Survey Method. The observational method is most common in the natural sciences, especially in fields such as biology, geology and environmental science. It involves recording observations according to a plan, which prescribes what information to collect, where it should be sought, and how it should be recorded. In the observational method, the researcher does not control any of the variables. In fact, it is important that the research be carried out in such a manner that the investigations do not change the behaviour of what is being observed. Errors introduced as a result of observing a phenomenon are known as systematic errors because they apply to all observations. Once a valid statistical sample (see Chapter Four) of observations has been recorded, the researcher analyzes and interprets the data, and develops a theory or hypothesis, which explains the observations. The experimental method begins with a hypothesis. -

Advancing Science Communication.Pdf

SCIENCETreise, Weigold COMMUNICATION / SCIENCE COMMUNICATORS Scholars of science communication have identified many issues that may help to explain why sci- ence communication is not as “effective” as it could be. This article presents results from an exploratory study that consisted of an open-ended survey of science writers, editors, and science communication researchers. Results suggest that practitioners share many issues of concern to scholars. Implications are that a clear agenda for science communication research now exists and that empirical research is needed to improve the practice of communicating science. Advancing Science Communication A Survey of Science Communicators DEBBIE TREISE MICHAEL F. WEIGOLD University of Florida The writings of science communication scholars suggest twodominant themes about science communication: it is important and it is not done well (Hartz and Chappell 1997; Nelkin 1995; Ziman 1992). This article explores the opinions of science communication practitioners with respect to the sec- ond of these themes, specifically, why science communication is often done poorly and how it can be improved. The opinions of these practitioners are important because science communicators serve as a crucial link between the activities of scientists and the public that supports such activities. To intro- duce our study, we first review opinions as to why science communication is important. We then examine the literature dealing with how well science communication is practiced. Authors’Note: We would like to acknowledge NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center for provid- ing the funds todothis research. We alsowant tothank Rick Borcheltforhis help with the collec - tion of data. Address correspondence to Debbie Treise, University of Florida, College of Journalism and Communications, P.O. -

Philosophical Approaches to Qualitative Research

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons School of Social Work: Faculty Publications and Other Works Faculty Publications 2014 Philosophical Approaches to Qualitative Research Julia Pryce [email protected] Renée Spencer Jill Walsh Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/socialwork_facpubs Part of the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Pryce, Julia; Spencer, Renée; and Walsh, Jill. Philosophical Approaches to Qualitative Research. The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods, , : 81-98, 2014. Retrieved from Loyola eCommons, School of Social Work: Faculty Publications and Other Works, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/ 9780199811755.001.0001 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Social Work: Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. © Oxford University Press, 2014. CHAPTER Philosophical Approaches to 5 Qualitative Research Renée Spencer, Julia M. Pryce, and Jill Walsh Abstract This chapter reviews some of the major overarching philosophical approaches to qualitative inquiry and includes some historical background for each. Taking a “big picture” view, the chapter discusses post-positivism, constructivism, critical theory, feminism, and queer theory and offers a brief history of these -

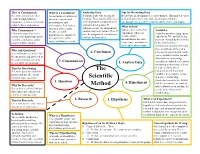

The Scientific Method Is a It Is a Possible Answer and Logical Problem-Solving Explanation to Your Question Process Used by Scientists

How to Communicate What is a Conclusion? Analyzing Data Tips for Recording Data Scientist communicate their A conclusion is a statement Scientists study data to look for Record data in an organized, accurate manner. This makes it easier results through journals, based on experimental meaning. They look for differences to identify patterns/ trends, make predictions, and draw magazines, websites, television, measurements and in the dependent variable between conclusions. Use a scientific journal, tables, charts, and graphs. radio, lectures, and posters. control and test groups. If observations. It includes a What is Data? summary of the results, differences exist, the independent Data are the results of the Variables Why Communicate? whether or not the variable may have had an effect. If Communicating discoveries experiment. They can Variables are what change in an hypothesis was supported, not, the independent variable may advances the knowledge of the include number experiment. The variable being the significance of the not have had any effect. scientific community, and it measurements like time, tested or changed by the scientist study, and future research. improves future studies. temperature, and mass, or is the independent or they can be observations. manipulated variable. Normally, there is only one of these at a Why Ask Questions? time so that experimental results It is important to clearly define 6. Conclusion can be attributed to that variable. the question being answered or Dependent or responding the problem being solved by 7. Communicate variables are what the scientist is the scientific investigation. 5. Analyze Data measuring or observing. If there Tips for Questioning is a direct link between Scientific questions should be The independent and dependent narrow and specific. -

Outdoor Education – Research Summary

Outdoor Education – Research Summary Research on outdoor education is synthesized below. Links to specific research papers and summaries are provided at the bottom. School performance increases when children learn outdoors1 A number of studies have documented increased school performance through outdoor education. Research has document increased standardized test scores, enhanced attitude about school, improved in-school behavior, improved attendance and overall enhanced student achievement when students learn in and about nature. In addition, outdoor education effectively employs a greater range of children’s intelligences. Many researchers contribute the increase in performance to increased relevance and hands-on experience of learning outdoors. Learning outdoors is healthy2 Learning outdoors is active and increases students’ physical, mental and social health. Some studies have even shown follow-up (e.g., non-school) physical activity increases with outdoor learning. Access to nature has also been shown to decrease the symptoms of ADHD. Outdoor learning and access to nature also decrease stress levels of students and teachers. Learning outdoors supports child development3 Children greatly benefit developmentally from being outdoors. Outdoor education and play support emotional, behavioral and intellectual development. Studies have shown that students who learn outdoors develop: a sense of self, independence, confidence, creativity, decision-making and problem-solving skills, empathy towards others, motor skills, self-discipline and initiative. Teaching and learning outdoors is fun4 Often, the outdoors provides a change of pace from the classroom, which students and teachers enjoy. Studies have shown increased student enthusiasm for learning outdoors. Learning outdoors helps develop a sense of place and civic attitudes and behaviors5 Outdoor experiences help students increase their understanding of their natural and human communities which leads to a sense of place. -

Deconstructing Public Administration Empiricism

Deconstructing Public Administration Empiricism A paper written for Anti-Essentialism in Public Administration a conference in Fort Lauderdale, Florida March 2 and 3, 2007 Larry S. Luton Graduate Program in Public Administration Eastern Washington University 668 N. Riverpoint Blvd., Suite A Spokane, WA 99202-1660 509/358-2247 voice 509/358-2267 fax [email protected] Deconstructing Public Administration Empiricism: Short Stories about Empirical Attempts to Study Significant Concepts and Measure Reality Larry S. Luton Eastern Washington University Like much social science empiricism, public administration empiricism at its best recognizes that it presents probabilistic truth claims rather than universalistic ones. In doing so, public administration empiricists are (to a degree) recognizing the tenuousness of their claim that their approach to research is better connected to reality than research that does not adhere to empiricist protocols. To say that one is 95% confident that an empirical model explains 25% of the variation being studied is not a very bold claim about understanding reality. They are also masking a more fundamental claim that they know an objective reality exists. The existence of an objective reality is the essential foundation upon which empiricism relies for its claim to provide a research approach that is superior to all others and, therefore, is in a position to set the standards to which all research should be held (King, Keohane, & Verba 1994; Brady & Collier, 2004). In one of the most direct expressions of this claim, Meier has stated “There is an objective reality” (Meier 2005, p. 664). In support of that claim, he referenced 28,000 infant deaths in the U.S. -

2 Research Philosophy and Qualitative Interviews

CHAPTER 2 RESEARCH PHILOSOPHY AND QUALITATIVE INTERVIEWS IN THIS CHAPTER: CHOOSING A PHILOSOPHY OF RESEARCH DIFFERENCES BETWEEN POSITIVIST AND NATURALIST–CONSTRUCTIONIST PARADIGMS AN ILLUSTRATION OF THE DIFFERENCES IN PRACTICE VARIATIONS ON THE CORE PARADIGM Positivism Yields to Postpositivism Naturalist and Interpretive Constructionist Perspectives Critical, Feminist, and Postmodern Perspectives TOWARD THE RESPONSIVE INTERVIEWING MODEL 13 14 QUALITATIVE INTERVIEWING v INTRODUCTION Which data-gathering tools you use depends largely on the research question at hand. You do not use interviewing to analyze census data; you don’t count to get descriptions of what happened in a closed-door meeting. In practice, researchers choose topics that lend themselves to quantitative or qualitative techniques based on their interests, personalities, and talents. If you enjoy talking with people and shudder just thinking about endless streams of numbers, you are more likely to choose a project suitable for in-depth interviewing than one requiring reams of statistical data. In addition, the choice of techniques also depends Not that long ago, many quantitative on your willingness to accept the assumptions researchers looked down on any project that did underlying each set of tools. Researchers who not involve precise measurement; they rejected use quantitative tools, techniques that empha- observational research and open-ended inter- size measuring and counting, are called posi- viewing as unscientific. Qualitative researchers tivists; those who prefer the qualitative tools were equally critical of positivists’ work, arguing of observation, questioning, and description are that the positivists’ search for generalizable rules called naturalists. Positivists and naturalists dif- and their focus on quantification ignored mat- fer in their assumptions about what is important ters that are important but not easily counted to study, what can be known, what research and denied the complexity and the conditional tools and designs are appropriate, and what nature of reality. -

Postpositivism and Accounting Research : a (Personal) Primer on Critical Realism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Online Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal Volume 4 Issue 4 Australasian Accounting Business and Article 2 Finance Journal 2010 Postpositivism and Accounting Research : A (Personal) Primer on Critical Realism Jayne Bisman Charles Sturt University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/aabfj Copyright ©2010 Australasian Accounting Business and Finance Journal and Authors. Recommended Citation Bisman, Jayne, Postpositivism and Accounting Research : A (Personal) Primer on Critical Realism, Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, 4(4), 2010, 3-25. Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Postpositivism and Accounting Research : A (Personal) Primer on Critical Realism Abstract This paper presents an overview and primer on the postpositivist philosophy of critical realism. The examination of this research paradigm commences with the identification of the underlying motivations that prompted a personal exploration of critical realism. A brief review of ontology, epistemology and methodology and the research philosophies and methods popularly applied in accounting is then provided. The meta-theoretical basis of critical realism and the ontological and epistemological assumptions that go towards establishing the ‘truth’ and validity criteria underpinning this paradigm are detailed, and the relevance and potential applications of critical realism to accounting research are also discussed. The purpose of this discussion is to make a call to diversify the approaches to accounting research, and – specifically – ot assist researchers to realise the potential for postpositivist multiple method research designs in accounting.