Estienne Roger's Foreign Composers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9. Vivaldi and Ritornello Form

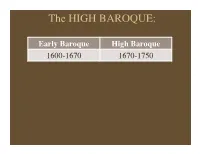

The HIGH BAROQUE:! Early Baroque High Baroque 1600-1670 1670-1750 The HIGH BAROQUE:! Republic of Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! Grand Canal, Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio VIVALDI (1678-1741) Born in Venice, trains and works there. Ordained for the priesthood in 1703. Works for the Pio Ospedale della Pietà, a charitable organization for indigent, illegitimate or orphaned girls. The students were trained in music and gave frequent concerts. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Thus, many of Vivaldi’s concerti were written for soloists and an orchestra made up of teen- age girls. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO It is for the Ospedale students that Vivaldi writes over 500 concertos, publishing them in sets like Corelli, including: Op. 3 L’Estro Armonico (1711) Op. 4 La Stravaganza (1714) Op. 8 Il Cimento dell’Armonia e dell’Inventione (1725) Op. 9 La Cetra (1727) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO In addition, from 1710 onwards Vivaldi pursues career as opera composer. His music was virtually forgotten after his death. His music was not re-discovered until the “Baroque Revival” during the 20th century. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Vivaldi constructs The Model of the Baroque Concerto Form from elements of earlier instrumental composers *The Concertato idea *The Ritornello as a structuring device *The works and tonality of Corelli The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The term “concerto” originates from a term used in the early Baroque to describe pieces that alternated and contrasted instrumental groups with vocalists (concertato = “to contend with”) The term is later applied to ensemble instrumental pieces that contrast a large ensemble (the concerto grosso or ripieno) with a smaller group of soloists (concertino) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Corelli creates the standard concerto grosso instrumentation of a string orchestra (the concerto grosso) with a string trio + continuo for the ripieno in his Op. -

Natura Artificiale Di Vivaldi

TORINO Martedì 5 settembre Conservatorio Giuseppe Verdi ore 17 LA NATURA ARTIFICIALE DI VIVALDI natura www.mitosettembremusica.it LA NATURA ARTIFICIALE DI VIVALDI Nei primissimi anni del Settecento, intrisi di razionalismo, si parla in continuazione di «Natura» come modello, e la naturalezza è il fine d’ogni arte. Quello che crea Vivaldi, molto baroccamente, è una finta natura: l’estremo artificio formale mascherato da gesto normale, spontaneo. E tutti ci crederanno. Il concerto è preceduto da una breve introduzione di Stefano Catucci Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) Concerto in la minore per due violini e archi da L’Estro Armonico op. 3 n. 8 RV 522a Allegro – [Adagio] – [Allegro] Sonata in sol maggiore per violino, violoncello e basso continuo RV 820 Allegro – Adagio – Allegro Concerto in re minore per violino, archi e basso continuo RV 813 (ms. Wien, E.M.) Allegro – [Adagio] – Allegro – Adagio – Andante – Largo – Allegro Concerto in sol maggiore per flauto traversiere, archi e basso continuo RV 438 Allegro – Larghetto – Allegro Sonata in re minore per due violini e basso continuo “La follia” op. 1 n. 12 RV 63 Tema (Adagio). Variazioni Giovanni Stefano Carbonelli (1694-1772) Sonata op. 1 n. 2 in re minore Adagio – Allegro Allegro Andante Aria Antonio Vivaldi Concerto in mi minore per violino, archi e basso continuo da La Stravaganza op. 4 n. 2 RV 279 Allegro – Largo – Allegro Modo Antiquo Federico Guglielmo violino principale Raffaele Tiseo, Paolo Cantamessa, Stefano Bruni violini Pasquale Lepore viola Bettina Hoffmann violoncello Federico Bagnasco contrabbasso Andrea Coen clavicembalo Federico Maria Sardelli direttore e flauto traversiere /1 Vivaldi natura renovatur. -

New York City Ballet MOVES Tuesday and Wednesday, October 24–25, 2017 7:30 Pm

New York City Ballet MOVES Tuesday and Wednesday, October 24–25, 2017 7:30 pm Photo:Photo: Benoit © Paul Lemay Kolnik 45TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON 2017/2018 Great Artists. Great Audiences. Hancher Performances. ARTISTIC DIRECTOR PETER MARTINS ARTISTIC ADMINISTRATOR JEAN-PIERRE FROHLICH THE DANCERS PRINCIPALS ADRIAN DANCHIG-WARING CHASE FINLAY ABI STAFFORD SOLOIST UNITY PHELAN CORPS DE BALLET MARIKA ANDERSON JACQUELINE BOLOGNA HARRISON COLL CHRISTOPHER GRANT SPARTAK HOXHA RACHEL HUTSELL BAILY JONES ALEC KNIGHT OLIVIA MacKINNON MIRIAM MILLER ANDREW SCORDATO PETER WALKER THE MUSICIANS ARTURO DELMONI, VIOLIN ELAINE CHELTON, PIANO ALAN MOVERMAN, PIANO BALLET MASTERS JEAN-PIERRE FROHLICH CRAIG HALL LISA JACKSON REBECCA KROHN CHRISTINE REDPATH KATHLEEN TRACEY TOURING STAFF FOR NEW YORK CITY BALLET MOVES COMPANY MANAGER STAGE MANAGER GREGORY RUSSELL NICOLE MITCHELL LIGHTING DESIGNER WARDROBE MISTRESS PENNY JACOBUS MARLENE OLSON HAMM WARDROBE MASTER MASTER CARPENTER JOHN RADWICK NORMAN KIRTLAND III 3 Play now. Play for life. We are proud to be your locally-owned, 1-stop shop Photo © Paul Kolnik for all of your instrument, EVENT SPONSORS accessory, and service needs! RICHARD AND MARY JO STANLEY ELLIE AND PETER DENSEN ALLYN L. MARK IOWA HOUSE HOTEL SEASON SPONSOR WEST MUSIC westmusic.com Cedar Falls • Cedar Rapids • Coralville Decorah • Des Moines • Dubuque • Quad Cities PROUD to be Hancher’s 2017-2018 Photo: Miriam Alarcón Avila Season Sponsor! Play now. Play for life. We are proud to be your locally-owned, 1-stop shop for all of your instrument, accessory, and service needs! westmusic.com Cedar Falls • Cedar Rapids • Coralville Decorah • Des Moines • Dubuque • Quad Cities PROUD to be Hancher’s 2017-2018 Season Sponsor! THE PROGRAM IN THE NIGHT Music by FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN Choreography by JEROME ROBBINS Costumes by ANTHONY DOWELL Lighting by JENNIFER TIPTON OLIVIA MacKINNON UNITY PHELAN ABI STAFFORD AND AND AND ALEC KNIGHT CHASE FINLAY ADRIAN DANCHIG-WARING Piano: ELAINE CHELTON This production was made possible by a generous gift from Mrs. -

Antonio Lucio VIVALDI

AN IMPORTANT NOTE FROM Johnstone-Music ABOUT THE MAIN ARTICLE STARTING ON THE FOLLOWING PAGE: We are very pleased for you to have a copy of this article, which you may read, print or save on your computer. You are free to make any number of additional photocopies, for johnstone-music seeks no direct financial gain whatsoever from these articles; however, the name of THE AUTHOR must be clearly attributed if any document is re-produced. If you feel like sending any (hopefully favourable) comment about this, or indeed about the Johnstone-Music web in general, simply vis it the ‘Contact’ section of the site and leave a message with the details - we will be delighted to hear from you ! Una reseña breve sobre VIVALDI publicado por Músicos y Partituras Antonio Lucio VIVALDI Antonio Lucio Vivaldi (Venecia, 4 de marzo de 1678 - Viena, 28 de julio de 1741). Compositor del alto barroco, apodado il prete rosso ("el cura rojo" por ser sacerdote y pelirrojo). Compuso unas 770 obras, entre las cuales se cuentan 477 concerti y 46 óperas; especialmente conocido a nivel popular por ser el autor de Las cuatro estaciones. johnstone-music Biografia Vivaldi un gran compositor y violinista, su padre fue el violinista Giovanni Batista Vivaldi apodado Rossi (el Pelirrojo), fue miembro fundador del Sovvegno de’musicisti di Santa Cecilia, organización profesional de músicos venecianos, así mismo fue violinista en la orquesta de la basílica de San Marcos y en la del teatro de S. Giovanni Grisostomo., fue el primer maestro de vivaldi, otro de los cuales fue, probablemente, Giovanni Legrenzi. -

BMC 36 - VIVALDI-BACH: Concerto Transcriptions for Harpsichord

BMC 36 - VIVALDI-BACH: Concerto Transcriptions for Harpsichord Antonio Vivaldi was born in Venice on March 4th, 1678. Though ordained a priest in 1703, within a year of being ordained – according to his own account – he no longer wished to celebrate mass because of physical complaints ("tightness of the chest") which pointed to angina pectoris, asthmatic bronchitis, or a nervous disorder. It is also possible that Vivaldi was simulating illness – there is a story that he sometimes left the altar in order quickly to jot down a musical idea in the sacristy.... In any event he had become a priest against his own will, perhaps because, in his day, training for the priesthood was often the only possible way for a poor family to obtain free schooling. Vivaldi was employed for most of his working life by the Ospedale della Pietà. Often termed an "orphanage", this Ospedale was in fact a home for the female offspring of noblemen and their numerous dalliances with their mistresses. The Ospedale was thus well endowed by the "anonymous" fathers; its furnishings bordered on the opulent, the young ladies were well looked-after, and the musical standards among the highest in Venice. Many of Vivaldi's Concerti would have been performed before Venetian audiences with his many talented pupils. In 1711 twelve new Concerto compositions were published in Amsterdam by the music publisher Estienne Roger under the title l'Estro armonico (Harmonic Inspiration). This was to be the start of an important alliance which greatly expedited the dissemination of Vivaldi's music throughout Europe. L'estro armonico was followed by La stravaganza in 1714, Duo and Trio Sonatas, Op. -

Antonio Vivaldi from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Antonio Vivaldi From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Antonio Lucio Vivaldi (Italian: [anˈtɔːnjo ˈluːtʃo viˈvaldi]; 4 March 1678 – 28 July 1741) was an Italian Baroque composer, virtuoso violinist, teacher and cleric. Born in Venice, he is recognized as one of the greatest Baroque composers, and his influence during his lifetime was widespread across Europe. He is known mainly for composing many instrumental concertos, for the violin and a variety of other instruments, as well as sacred choral works and more than forty operas. His best-known work is a series of violin concertos known as The Four Seasons. Many of his compositions were written for the female music ensemble of the Ospedale della Pietà, a home for abandoned children where Vivaldi (who had been ordained as a Catholic priest) was employed from 1703 to 1715 and from 1723 to 1740. Vivaldi also had some success with expensive stagings of his operas in Venice, Mantua and Vienna. After meeting the Emperor Charles VI, Vivaldi moved to Vienna, hoping for preferment. However, the Emperor died soon after Vivaldi's arrival, and Vivaldi himself died less than a year later in poverty. Life Childhood Antonio Lucio Vivaldi was born in 1678 in Venice, then the capital of the Republic of Venice. He was baptized immediately after his birth at his home by the midwife, which led to a belief that his life was somehow in danger. Though not known for certain, the child's immediate baptism was most likely due either to his poor health or to an earthquake that shook the city that day. -

JAMES CUMMINS Bookseller Catalogue 124

JAMES CUMMINS bookseller catalogue 124 JAMES CUMMINS bookseller catalogue 124 To place your order, call, write, e-mail or fax: james cummins bookseller 699 Madison Avenue, New York City, 10065 Telephone (212) 688-6441 Fax (212) 688-6192 [email protected] jamescumminsbookseller.com hours: Monday – Friday 10:00 – 6:00, Saturday 10:00 – 5:00 Members A.B.A.A., I.L.A.B. front cover: item 67 inside front cover: item 78 inside rear cover: item 76 rear cover: item 8 photography by nicole neenan terms of payment: All items, as usual, are guaranteed as described and are returnable within 10 days for any reason. All books are shipped UPS (please provide a street address) unless otherwise requested. Overseas orders should specify a shipping preference. All postage is extra. New clients are requested to send remittance with orders. Libraries may apply for deferred billing. All New York and New Jersey residents must add the appropriate sales tax. We accept American Express, Master Card, and Visa. “adrift in the streets” of new york city: presentation copy ALGER, Horatio, Jr. The Young Outlaw, or, Adrift in the Streets. With four plates (frontispiece, pictorial title for Tattered Tom, Second Series preceding title, 2 plates at pp. 108, 208). [2] f. (blanks); [4, ads], viii, [9]-256, [2, blank] pp. 8vo, Boston: Loring, [1875]. First edition. Original purple publisher’s cloth, title in gilt, boards stamped in blind. Spine and fore edge of upper board faded, else near fne. Presentation copy, inscribed on the fyleaf, “Robert Lloyd from the Author.” “Canal Street’s about a mile of. -

Concerto.MUS

ANTONIO VIVALDI (Venezia 1678 - Wien 1741) CONCERTO RV 93 (F. XII n. 15) con 2 Violini Leuto, e Basso Del Vivaldi P.S.E. Il Conte Wrttby Urtext edition by Fabio Rizza based on the original manuscript housed in the Biblioteca Nazionale, Turin, Italy, "Renzo Giordani Collection", vol. 35, fol. 297 - 302 [email protected] PREFACE 3 CONCERTO RV 93 4 1. [Allegro giusto] 4 2. Largo 8 3. Allegro 10 BIBLIOGRAPHY/BIBLIOGRAFIA 13 DISCOGRAPHY/DISCOGRAFIA 14 PREFACE Probably this Concerto con 2 Violini Leuto, e Basso has been written in the early 1730s, when Vivaldi was in Prague, and it's dedicated to a Bohemian Count, Johann Joseph von Wrtby (Jan Josef Vrtba, according to the Czech form). The present edition is a faithful copy of the autograph housed in the Biblioteca Nazionale, Turin (Italy), "Renzo Giordani Collection", vol. 35, fol. 297 - 302. I've corrected only an obvious mistake (a C-sharp instead of a B) in measure 9 of the second movement. The music has been engraved in Finale 98. PREFAZIONE È probabile che questo Concerto con 2 Violini Leuto, e Basso sia stato scritto intorno al 1730, mentre Vivaldi si trovava a Praga, ed è dedicato al conte boemo Johann Joseph von Wrtby (o Jan Josef Vrtba, secondo la grafia ceca). Questa edizione è una copia fedele del manoscritto autografo conservato presso la Biblioteca Nazionale di Torino, fondo "Renzo Giordani", vol. 35, fol. 297 - 302. Mi sono limitato a correggere un palese errore (un do diesis al posto di un si) a misura 9 del secondo movimento. -

The Journal of the Viola Da Gamba Society

The Journal of the Viola da Gamba Society Text has been scanned with OCR and is therefore searchable. The format on screen does not conform with the printed Chelys. The original page numbers have been inserted within square brackets: e.g. [23]. Footnotes here run in sequence through the whole article rather than page by page. The pages labelled ‘The Viola da Gamba Society Provisional Index of Viol Music’ in some early volumes are omitted here since they are up-dated as necessary as The Viola da Gamba Society Thematic Index of Music for Viols, ed. Gordon Dodd and Andrew Ashbee, 1982-, available on-line. All items have been bookmarked. Contents of Volume 30 (2002) Editorial, p.2 Virginia Brookes: In Nomine: an obscure designation Chelys vol. 30, pp. 4-10 Ian Payne: New Light on ‘New Fashions’ by William Cobbold (1560-1639) of Norwich Chelys vol. 30, pp. 11-37 Anne Graf and David A. Ramsey: A Seventeenth-Century Music Manuscript from Ratby, Leicestershire Chelys vol. 30, pp. 38-46 Samantha Owens: The Viol at the Württemberg Court c1717: Identification of the Hand Gamba Chelys vol. 30, pp. 47-59 Review: Chelys vol. 30, pp. 60-61 Letters to the editor: Chelys vol. 30, pp. 62-64 EDITORIAL The contents of the present issue of Chelys serve as a reminder, if any were needed, that we see the music of the past through a glass, darkly. The first article describes the long-standing mystery of the In Nomine, now happily solved, but the other three all deal with topics which still involve a degree of uncertainty: we are never going to be completely sure what was in a missing part, or why a fragment of lyra tablature turned up in a Leicestershire farmhouse, and we may never discover absolute confirmation of what German musicians meant by a 'handt Gamba'. -

Irish Spurge (Euphorbia Hyberna) in England: Native Or Naturalised?

British & Irish Botany 1(3): 243-249, 2019 Irish Spurge (Euphorbia hyberna) in England: native or naturalised? John Lucey* Kilkenny, Ireland *Corresponding author: John Lucey, email: [email protected] This pdf constitutes the Version of Record published on 13th August 2019 Abstract Most modern authorities have considered Euphorbia hyberna to be native in Britain but with the possibility that it could have been introduced from Ireland. The results from a literature survey, on the historical occurrence of the species, strongly suggest that it was introduced and has become naturalised at a few locations in south-west England. Keywords: status; Cornwall; Devon; Lusitanian; horticulture Introduction The Irish Spurge (Euphorbia hyberna L.) is an extremely rare plant in England with only recent occurrences for west Cornwall, north Devon and south Somerset (Stace, 2010) although now extinct in the last vice-county (Crouch, 2014). The earliest records for the three vice-counties contained in the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland (BSBI) Database (DDb) are: 1842 v.c.4 Lynton (Ward, N.B. More, W.S.) 1883 vc.1 Portreath (Marquand, E.D.) 1898 v.c.5 Badgworthy Valley (Salmon, C.E.) As the only element of the so-called Lusitanian flora in England, with an extremely restricted distribution pattern in the south-west, the species represents an unresolved biogeographical conundrum: native or naturalised? A review of the historical literature can provide valuable information on a species’ occurrence and thus may help in determining if it may have been introduced to a region. Botanical and other literature sources on the historical occurrence of E. -

Colista Or Corelli? a «Waiting Room» for the Trio Sonata Ahn. 16*

Philomusica on-line 16 (2017) Colista or Corelli? A «waiting room» for the trio sonata Ahn. 16* Antonella D’Ovidio Università di Firenze [email protected] § Studi recenti sulle fonti, manoscritte e § Recent research on manuscript and a stampa, dei lavori corelliani hanno printed sources of Corelli’s output riaperto la discussione attorno alle have re-opened discussion on doubt- opere dubbie e a quelle ‘senza numero ful works and have led to a new d’opera’ del compositore, portando così revision of Marx’s classification of ad una parziale revisione dei criteri Corelli’s catalogue. utilizzati da Marx nel suo catalogo While the solo sonatas of doubtful corelliano. attribution have already been re- Mentre la trasmissione manoscritta examined, there is still much to be delle sonate per violino è stata profon- done on doubtful trio sonatas. In this damente riesaminata, molto ancora respect, this essay focuses on a spe- resta da fare nel caso delle sonate a tre cific case: the conflicting attribution non attribuibili con certezza a Corelli. A of trio sonata Ahn. 16 classified by tale proposito, l’articolo si focalizza su Marx among Corelli’s doubtful works un caso specifico, ovvero la sonata a tre and attested in a group of English Ahn. 16. Essa è oggi attestata da un sources, only rarely examined by gruppo di testimoni di provenienza Corelli scholars. In some sources inglese, solo raramente esaminati dagli Ahn. 16 is attributed to Corelli, in studiosi corelliani. La sonata presenta others to the Roman lutenist and un’attri-buzione conflittuale: in alcuni composer Lelio Colista, in others no manoscritti è assegnata a Corelli, in ascription is reported. -

Music Migration in the Early Modern Age

Music Migration in the Early Modern Age Centres and Peripheries – People, Works, Styles, Paths of Dissemination and Influence Advisory Board Barbara Przybyszewska-Jarmińska, Alina Żórawska-Witkowska Published within the Project HERA (Humanities in the European Research Area) – JRP (Joint Research Programme) Music Migrations in the Early Modern Age: The Meeting of the European East, West, and South (MusMig) Music Migration in the Early Modern Age Centres and Peripheries – People, Works, Styles, Paths of Dissemination and Influence Jolanta Guzy-Pasiak, Aneta Markuszewska, Eds. Warsaw 2016 Liber Pro Arte English Language Editor Shane McMahon Cover and Layout Design Wojciech Markiewicz Typesetting Katarzyna Płońska Studio Perfectsoft ISBN 978-83-65631-06-0 Copyright by Liber Pro Arte Editor Liber Pro Arte ul. Długa 26/28 00-950 Warsaw CONTENTS Jolanta Guzy-Pasiak, Aneta Markuszewska Preface 7 Reinhard Strohm The Wanderings of Music through Space and Time 17 Alina Żórawska-Witkowska Eighteenth-Century Warsaw: Periphery, Keystone, (and) Centre of European Musical Culture 33 Harry White ‘Attending His Majesty’s State in Ireland’: English, German and Italian Musicians in Dublin, 1700–1762 53 Berthold Over Düsseldorf – Zweibrücken – Munich. Musicians’ Migrations in the Wittelsbach Dynasty 65 Gesa zur Nieden Music and the Establishment of French Huguenots in Northern Germany during the Eighteenth Century 87 Szymon Paczkowski Christoph August von Wackerbarth (1662–1734) and His ‘Cammer-Musique’ 109 Vjera Katalinić Giovanni Giornovichi / Ivan Jarnović in Stockholm: A Centre or a Periphery? 127 Katarina Trček Marušič Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Migration Flows in the Territory of Today’s Slovenia 139 Maja Milošević From the Periphery to the Centre and Back: The Case of Giuseppe Raffaelli (1767–1843) from Hvar 151 Barbara Przybyszewska-Jarmińska Music Repertory in the Seventeenth-Century Commonwealth of Poland and Lithuania.