UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Talking to Strangers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Queerness and Chinese Modernity: the Politics of Reading Between East and East a Dissertati

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Queerness and Chinese Modernity: The Politics of Reading Between East and East A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Alvin Ka Hin Wong Committee in Charge: Professor Yingjin Zhang, Co-Chair Professor Lisa Lowe, Co-Chair Professor Patrick Anderson Professor Rosemary Marangoly George Professor Larissa N. Heinrich 2012 Copyright Alvin Ka Hin Wong, 2012 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Alvin Ka Hin Wong is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair ________________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2012 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page …………………………………………………….……………….….…iii Table of Contents ………………………………………………………………..…….…iv List of Illustrations ……………………………………………………………….…........v Acknowledgments …………………………………………………………………….....vi Vita …………………………………………………….…………………………….…...x Abstract of the Dissertation ………………………………………………….……….….xi INTRODUCTION.……………………………………………………………….……....1 CHAPTER ONE. Queering Chineseness and Kinship: Strategies of Rewriting by Chen Ran, Chen Xue and Huang Biyun………………………….………...33 -

Climate-Change Journalism in China: Opportunities for International

Climate-change journalism in China: opportunities for international cooperation By Sam Geall Foreword by Hu Shuli 中国气候变化报道: 国际合作中的机遇 山姆·吉尔 序——胡舒立 Climate-change journalism in China: opportunities for international cooperation 中国气候变化报道:国际合作中的机遇 © International Media Support 2011. Any reproduction, modification, publication, transmission, transfer, sale distribution, display or exploitation of this information, in any form or by any means, or its storage in a retrieval system, whether in whole or in part, without the express written permission of the individual copyright holder is prohibited without prior approval by IMS. Cover image by Angel Hsu. © 国际媒体支持组织 版权所有 2011 任何媒体、网站或个人未经“国际媒体支持组织”的书面许可,不得引用、复 制、转载、摘编、发售、储存于检索系统,或以其他任何方式非法使用本报告全 部或部分内容。 封面照片由徐安琪摄。 International Media Support (IMS) Communications Unit, Nørregade 18, Copenhagen K 1165, Denmark Phone: +4588327000, Fax: +4533120099 Email: [email protected] www.i-m-s.dk Caixin Media Floor 15/16, Tower A, Winterless Center, No.1 Xidawanglu, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100026, P.R.China http://english.caing.com/ chinadialogue Suite 306 Grayston Centre, 28 Charles Square, London N1 6HT, United Kingdom Phone: +442073244767 Email: [email protected] www.chinadialogue.net Climate-change journalism in China: opportunities for international cooperation By Sam Geall1 Foreword by Hu Shuli2 p4 1. Sam Geall is deputy editor of chinadialogue. The author acknowledges generous contributions to the research and analysis in this report from Li Hujun, Wang Haotong, Eliot Gao and Lisa Lin. Essential input and support were also provided by Martin Breum, Martin Gottske, Isabel Hilton, Tan Copsey, Li Dawei, Ma Ling, Hu Shuli, Bruce Lewenstein and Jia Hepeng. 2. Hu Shuli is editor-in-chief of Caixin Media (the Beijing-based media group that publishes Century Weekly and China Reform), the former founding editor of Caijing magazine and a prominent investigative journalist and commentator. -

1 Comrade China on the Big Screen

COMRADE CHINA ON THE BIG SCREEN: CHINESE CULTURE, HOMOSEXUAL IDENTITY, AND HOMOSEXUAL FILMS IN MAINLAND CHINA By XINGYI TANG A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN MASS COMMUNICATION UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Xingyi Tang 2 To my beloved parents and friends 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First of all, I would like to thank some of my friends, for their life experiences have inspired me on studying this particular issue of homosexuality. The time I have spent with them was a special memory in my life. Secondly, I would like to express my gratitude to my chair, Dr. Churchill Roberts, who has been such a patient and supportive advisor all through the process of my thesis writing. Without his encouragement and understanding on my choice of topic, his insightful advices and modifications on the structure and arrangement, I would not have completed the thesis. Also, I want to thank my committee members, Dr. Lisa Duke, Dr. Michael Leslie, and Dr. Lu Zheng. Dr. Duke has given me helpful instructions on qualitative methods, and intrigued my interests in qualitative research. Dr. Leslie, as my first advisor, has led me into the field of intercultural communication, and gave me suggestions when I came across difficulties in cultural area. Dr. Lu Zheng is a great help for my defense preparation, and without her support and cooperation I may not be able to finish my defense on time. Last but not least, I dedicate my sincere gratitude and love to my parents. -

TRANSFORMATIONS Acomparative Study of Social Transfomtions

' TRANSFORMATIONS acomparative study of social transfomtions CSST WORKING PAPERS The University of Michigan Ann Arbor "Reclaiming the Epistemological 'Other': Narrative and the Social Constitution of Identity" Margaret R. Somers and Gloria D. Gibson CSST Working CRSO Working Paper #94 Paper #499 June 1993 RECLAIMING THE EPISTEMOLOGICAL "OTHER": NARRATIVE AND THE SOCIAL CONSTITUTION OF IDENTITY* Margaret R. Somers and Gloria D. Gibson Department of Sociology University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI 48109 (313) 764-6324 Bitnet: userGD52@umichum or Internet: [email protected] Forthcoming in Craig Calhoun ed., From Persons to Nations: The Social Constitution of Identities, London: Basil Blackwell. *An earlier version of this chapter (by Somers) was presented at the 1992 American Sociological Association Meetings, Pittsburgh, Pa. We are very grateful to Elizabeth Long for her comments as the discussant on that panel, and to Renee Anspach, Craig Calhoun, and Marc Steinberg for their useful suggestions on that earlier version. RECLAIMING THE EPISTEMOLOGICAL "OTHER": NARRATIVE AND THE SOCIAL CONSTITUTION OF IDENTITY "A Word on Categories" As I write, my editor at Harvard University Press is waging something of a struggle with the people at the Library of Congress about how this book is to be categorized for cataloging purposes. The librarians think "Afro- Americans--Civil Rights" and "Law Teachers" would be nice. I told my editor to hold out for "Autobiography," "Fiction," "Gender Studies," and "Medieval Medicine." This battle seems appropriate enough since the book is not exclusively about race or law but also about boundary. While being black has been the powerful social attribution in my life, it is only one of a number of governing narratives or presiding fictions by which I am constantly reconfiguring myself in the world. -

1 Craig Calhoun Administrative and Leadership Experience

Craig Calhoun Administrative and Leadership Experience University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Founding Director, Program in Social Theory and Cross-Cultural Studies, 1989-96 (Acting Director, 1988-89); Director, Office of International Programs and Chair, Curriculum in International Studies, 1989- 93; Oversaw study abroad, Fulbright and other faculty exchanges, and one of the largest majors on campus Founding Director, University Center for International Studies, 1993-96; Led successful effort to bring 5 Title VI Centers to UNC; Directed one Center Dean of the Graduate School, 1994-96. Founded Carolina Society of Fellows substantially increasing PhD student funding Other: Administrative Board of the Library, 1981-84; Committee on Computers in the Arts and Sciences, 1982; Graduate School Nominating Committee, Social Sciences, 1982-83; 1986-87 (chair); Committee on Research in African Studies, 1984-85; Faculty Advisor, Carolina Symposium, 1985-86; 1987-8; Faculty Council, 1985- 88, Executive Committee, 1993-94; Organizer, Institute for Research in Social Science Working Group on Social Theory, 1985-87; Advisory Committee on International Programs, 1985-88; Campus Housing Committee, 1986-7; Chancellor's Bicentennial Task Force on the University and Undergraduate Education, 1986-87; Faculty Advisor and Instructor, UNITAS: An Experiment in Multicultural Living and Learning, 1986-88; Chair, UNITAS Advisory Committee, 1990-96; Honors Advisory Board, 1987-90; Division of Social Sciences Advisory Council, 1987-90; Faculty Advisor, Fine Arts -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Across the Geo-political Landscape Chinese Women Intellectuals’ Political Networks in the Wartime Era 1937-1949 Guo, Xiangwei Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 Across the Geo-political Landscape: Chinese Women Intellectuals’ Political -

1.2 the Age and Gender Composition of the Labour Market

Copyright Undertaking This thesis is protected by copyright, with all rights reserved. By reading and using the thesis, the reader understands and agrees to the following terms: 1. The reader will abide by the rules and legal ordinances governing copyright regarding the use of the thesis. 2. The reader will use the thesis for the purpose of research or private study only and not for distribution or further reproduction or any other purpose. 3. The reader agrees to indemnify and hold the University harmless from and against any loss, damage, cost, liability or expenses arising from copyright infringement or unauthorized usage. IMPORTANT If you have reasons to believe that any materials in this thesis are deemed not suitable to be distributed in this form, or a copyright owner having difficulty with the material being included in our database, please contact [email protected] providing details. The Library will look into your claim and consider taking remedial action upon receipt of the written requests. Pao Yue-kong Library, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong http://www.lib.polyu.edu.hk GENDER IN FACTORY LIFE: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF MIGRANT WORKERS IN SHENZHEN FOXCONN DENG YUNXUE M.Phil The Hong Kong Polytechnic University 2012 THE HONG KONG POLYTECHNIC UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF APPLIED SOCIAL SCIENCES Gender in factory life: An ethnographic study of migrant workers in Shenzhen Foxconn Deng Yunxue A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy July 2012 Certificate of Originality I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it reproduces no material previously published or written, nor material that has been accepted for the award of any other degree of diploma, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. -

Historical Sociology in International Relations: Open Society, Research Programme and Vocation

George Lawson Historical sociology in international relations: open society, research programme and vocation Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Lawson, George (2007) Historical sociology in international relations: open society, research programme and vocation. International politics, 44 (4). pp. 343-368. DOI: 10.1057/palgrave.ip.8800195 © 2007 Palgrave Macmillan This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/2742/ Available in LSE Research Online: August 2012 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final manuscript accepted version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer review process. Some differences between this version and the published version may remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Historical Sociology in International Relations: Open Society, Research Programme and Vocation Article for International Politics forum on Historical Sociology April 2006 Abstract Over the last twenty years, historical sociology has become an increasingly conspicuous part of the broader field of International Relations (IR) theory, with advocates making a series of interventions in subjects as diverse as the origins and varieties of international systems over time and place, to work on the co-constitutive relationship between the international realm and state-society relations in processes of radical change. -

China's Foreign Policy Dilemma

February 2013 ANALYSIS LINDA JAKOBSON China’s Foreign Policy Program Director East Asia Dilemma Tel: +61 2 8238 9070 [email protected] E xecutive summary Foreign policy will not be a top priority of China’s new leader Xi Jinping. Xi is under pressure from many sectors of society to tackle China’s formidable domestic problems. To stay in power Xi must ensure continued economic growth and social stability. Due to the new leadership’s preoccupation with domestic issues, Chinese foreign policy can be expected to be reactive. This may have serious consequences because of the potentially explosive nature of two of China’s most pressing foreign policy challenges: how to decrease tensions with Japan over the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands and with Southeast Asian states over territorial claims in the South China Sea. A lack of attention by China’s senior leaders to these sovereignty disputes is a recipe for disaster. If a maritime or aerial incident occurs, nationalist pressure will narrow the room for manoeuvre of leaders in each of the countries involved in the incident. There are numerous foreign and security policy actors within China who favour Beijing taking a more forceful stance in its foreign policy. Regional stability could be at risk if China’s new leadership merely reacts as events unfold, as has too often been the case in recent years. LOWY INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL POLICY 31 Bligh Street Sydney NSW 2000 Tel: +61 2 8238 9000 Fax: +61 2 8238 9005 www.lowyinstitute.org The Lowy Institute for International Policy is an independent policy think tank. -

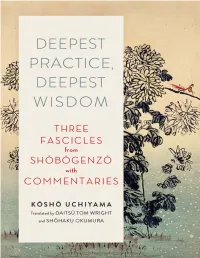

Deepest Practice, Deepest Wisdom

“A magnificent gift for anyone interested in the deep, clear waters of Zen—its great foundational master coupled with one of its finest modern voices.” —JISHO WARNER, former president of the Soto Zen Buddhist Association FAMOUSLY INSIGHTFUL AND FAMOUSLY COMPLEX, Eihei Dōgen’s writings have been studied and puzzled over for hundreds of years. In Deepest Practice, Deepest Wisdom, Kshō Uchiyama, beloved twentieth-century Zen teacher, addresses himself head-on to unpacking Dōgen’s wisdom from three fascicles (or chapters) of his monumental Shōbōgenzō for a modern audience. The fascicles presented here from Shōbōgenzō, or Treasury of the True Dharma Eye, include “Shoaku Makusa” or “Refraining from Evil,” “Maka Hannya Haramitsu” or “Practicing Deepest Wisdom,” and “Uji” or “Living Time.” Daitsū Tom Wright and Shōhaku Okumura lovingly translate Dōgen’s penetrating words and Uchiyama’s thoughtful commentary on each piece. At turns poetic and funny, always insightful, this is Zen wisdom for the ages. KŌSHŌ UCHIYAMA was a preeminent Japanese Zen master instrumental in bringing Zen to America. The author of over twenty books, including Opening the Hand of Thought and The Zen Teaching of Homeless Kodo, he died in 1998. Contents Introduction by Tom Wright Part I. Practicing Deepest Wisdom 1. Maka Hannya Haramitsu 2. Commentary on “Maka Hannya Haramitsu” Part II. Refraining from Evil 3. Shoaku Makusa 4. Commentary on “Shoaku Makusa” Part III. Living Time 5. Uji 6. Commentary on “Uji” Part IV. Comments by the Translators 7. Connecting “Maka Hannya Haramitsu” to the Pāli Canon by Shōhaku Okumura 8. Looking into Good and Evil in “Shoaku Makusa” by Daitsū Tom Wright 9. -

User Modeling and Personalization in the Microblogging Sphere

User Modeling and Personalization in the Microblogging Sphere Qi Gao . User Modeling and Personalization in the Microblogging Sphere Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Technische Universiteit Delft, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof.ir. K.C.A.M. Luyben, voorzitter van het College voor Promoties, in het openbaar te verdedigen op maandag 28 oktober 2013 om 15:00 uur door Qi GAO Bachelor of Engineering in Automation, Tongji University, geboren te Jiashan, Zhejiang, China. Dit proefschrift is goedgekeurd door de promotoren: Prof.dr.ir. G.J.P.M. Houben Samenstelling promotiecommissie: Rector Magnificus voorzitter Prof.dr.ir. G.J.P.M. Houben Technische Universiteit Delft, promotor Prof.dr. P. Brusilovsky University of Pittsburgh Prof.dr. P.M.E. De Bra Technische Universiteit Eindhoven Prof.dr. V.G. Dimitrova University of Leeds Prof.dr. A. Hanjalic Technische Universiteit Delft Dr. F. Abel XING AG Prof.dr.ir. D.H.J. Epema Technische Universiteit Delft (reservelid) SIKS Dissertation Series No. 2013-33 The research reported in this thesis has been carried out under the auspices of SIKS, the Dutch Research School for Information and Knowledge Systems. Published and distributed by: Qi Gao E-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 978-94-6186-227-3 Keywords: user modeling, personalization, recommender systems, semantic web, social web, microblog, twitter, sina weibo Copyright c 2013 by Qi Gao All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, in- cluding photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission of the author. -

Weibo's Role in Shaping Public Opinion and Political

Blekinge Institute of Technology School of Computing Department of Technology and Aesthetics WEIBO’S ROLE IN SHAPING PUBLIC OPINION AND POLITICAL PARTICIPATION IN CHINA Shajin Chen 2014 BACHELOR THESIS B.S. in Digital Culture Supervisor: Maria Engberg Chen 1 Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................2 2. INTERNET AND MICROBLOGGING IN CHINA ......................................................5 2.1 INTERNET, MEDIA AND POLITICAL LANDSCAPE IN CHINA: AN OVERVIEW .......................... 5 2.2 MICROBLOGGING AND CHINESE WEIBO .........................................................................7 2.3 SINA WEIBO: THE KING OF MICROBLOGGING IN CHINA ................................................... 8 3. DOMINANT FEATURES OF WEIBO IN SHAPING PUBLIC OPINION AND POLITICAL SPHERE ........................................................................................................10 3.1 INFORMATION DIFFUSION ............................................................................................11 3.2 OPINION LEADERS AND VERIFIED IDENTITY ..................................................................12 3.3 PLATFORM FOR FREE SPEECH, COLLECTIVE VOICE AND EXPOSURE ................................. 14 3.4 PARTICIPATION OF MASS MEDIA AND GOVERNMENT ......................................................15 4. CASE STUDIES ..............................................................................................................18 4.1