Securitas Im Perii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yalta Conference

Yalta Conference 1 The Conference All three leaders were attempting to establish an agenda for governing post-war Europe. They wanted to keep peace between post-world war countries. On the Eastern Front, the front line at the end of December 1943 re- mained in the Soviet Union but, by August 1944, So- viet forces were inside Poland and parts of Romania as part of their drive west.[1] By the time of the Conference, Red Army Marshal Georgy Zhukov's forces were 65 km (40 mi) from Berlin. Stalin’s position at the conference was one which he felt was so strong that he could dic- tate terms. According to U.S. delegation member and future Secretary of State James F. Byrnes, "[i]t was not a question of what we would let the Russians do, but what Yalta Conference in February 1945 with (from left to right) we could get the Russians to do.”[2] Moreover, Roosevelt Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin. Also hoped for a commitment from Stalin to participate in the present are Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov (far left); United Nations. Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Andrew Cunningham, RN, Marshal of the RAF Sir Charles Portal, RAF, Premier Stalin, insisting that his doctors opposed any (standing behind Churchill); General George C. Marshall, Chief long trips, rejected Roosevelt’s suggestion to meet at the of Staff of the United States Army, and Fleet Admiral William Mediterranean.[3] He offered instead to meet at the Black D. Leahy, USN, (standing behind Roosevelt). -

Please Download Issue 2 2012 Here

A quarterly scholarly journal and news magazine. June 2012. Vol. V:2. 1 From the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES) Academic life in newly Södertörn University, Stockholm founded Baltic States BALTIC WORLDSbalticworlds.com LANGUAGE &GYÖR LITERATUREGY DALOS SOFI OKSANEN STEVE sem-SANDBERG AUGUST STRINDBERG GYÖRGY DALOS SOFI OKSANEN STEVE sem-SANDBERG AUGUST STRINDBERG also in this issue ILL. LARS RODVALDR SIBERIA-EXILES / SOUNDPOETRY / SREBRENICA / HISTORY-WRITING IN BULGARIA / HOMOSEXUAL RIGHTS / RUSSIAN ORPHANAGES articles2 editors’ column Person, myth, and memory. Turbulence The making of Raoul Wallenberg and normality IN auGusT, the 100-year anniversary of seek to explain what it The European spring of Raoul Wallenberg’s birth will be celebrated. is that makes someone 2012 has been turbulent The man with the mission of protect- ready to face extraordinary and far from “normal”, at ing the persecuted Jewish population in challenges; the culture- least when it comes to Hungary in final phases of World War II has theoretical analyzes of certain Western Euro- become one of the most famous Swedes myth, monuments, and pean exemplary states, of the 20th century. There seem to have heroes – here, the use of affected as they are by debt been two decisive factors in Wallenberg’s history and the need for crises, currency concerns, astonishing fame, and both came into play moral exemplars become extraordinary political around the same time, towards the end of themselves the core of the solutions, and growing the 1970s. The Holocaust had suddenly analysis. public support for extremist become the focus of interest for the mass Finally: the historical political parties. -

YUGOSLAV-SOVIET RELATIONS, 1953- 1957: Normalization, Comradeship, Confrontation

YUGOSLAV-SOVIET RELATIONS, 1953- 1957: Normalization, Comradeship, Confrontation Svetozar Rajak Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy London School of Economics and Political Science University of London February 2004 UMI Number: U615474 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615474 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ” OF POUTICAL «, AN0 pi Th ^ s^ s £ £2^>3 ^7&2io 2 ABSTRACT The thesis chronologically presents the slow improvement of relations between Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, starting with Stalin’s death on 5 March 1953, through their full normalization in 1955 and 1956, to the renewed ideological confrontation at the end of 1956. The normalization of Yugoslav-Soviet relations brought to an end a conflict between Yugoslavia and the Eastern Bloc, in existence since 1948, which threatened the status quo in Europe. The thesis represents the first effort at comprehensively presenting the reconciliation between Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, between 1953 and 1957. It will also explain the motives that guided the leaderships of the two countries, in particular the two main protagonists, Josip Broz Tito and Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev, throughout this process. -

Organized Crime and the Russian State Challenges to U.S.-Russian Cooperation

Organized Crime and the Russian State Challenges to U.S.-Russian Cooperation J. MICHAEL WALLER "They write I'm the mafia's godfather. It was Vladimir Ilich Lenin who was the real organizer of the mafia and who set up the criminal state." -Otari Kvantrishvili, Moscow organized crime leader.l "Criminals Nave already conquered the heights of the state-with the chief of the KGB as head of a mafia group." -Former KGB Maj. Gen. Oleg Kalugin.2 Introduction As the United States and Russia launch a Great Crusade against organized crime, questions emerge not only about the nature of joint cooperation, but about the nature of organized crime itself. In addition to narcotics trafficking, financial fraud and racketecring, Russian organized crime poses an even greater danger: the theft and t:rafficking of weapons of mass destruction. To date, most of the discussion of organized crime based in Russia and other former Soviet republics has emphasized the need to combat conven- tional-style gangsters and high-tech terrorists. These forms of criminals are a pressing danger in and of themselves, but the problem is far more profound. Organized crime-and the rarnpant corruption that helps it flourish-presents a threat not only to the security of reforms in Russia, but to the United States as well. The need for cooperation is real. The question is, Who is there in Russia that the United States can find as an effective partner? "Superpower of Crime" One of the greatest mistakes the West can make in working with former Soviet republics to fight organized crime is to fall into the trap of mirror- imaging. -

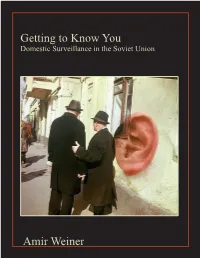

Getting to Know You. the Soviet Surveillance System, 1939-1957

Getting to Know You Domestic Surveillance in the Soviet Union Amir Weiner Forum: The Soviet Order at Home and Abroad, 1939–61 Getting to Know You The Soviet Surveillance System, 1939–57 AMIR WEINER AND AIGI RAHI-TAMM “Violence is the midwife of history,” observed Marx and Engels. One could add that for their Bolshevik pupils, surveillance was the midwife’s guiding hand. Never averse to violence, the Bolsheviks were brutes driven by an idea, and a grandiose one at that. Matched by an entrenched conspiratorial political culture, a Manichean worldview, and a pervasive sense of isolation and siege mentality from within and from without, the drive to mold a new kind of society and individuals through the institutional triad of a nonmarket economy, single-party dictatorship, and mass state terror required a vast information-gathering apparatus. Serving the two fundamental tasks of rooting out and integrating real and imagined enemies of the regime, and molding the population into a new socialist society, Soviet surveillance assumed from the outset a distinctly pervasive, interventionist, and active mode that was translated into myriad institutions, policies, and initiatives. Students of Soviet information systems have focused on two main features—denunciations and public mood reports—and for good reason. Soviet law criminalized the failure to report “treason and counterrevolutionary crimes,” and denunciation was celebrated as the ultimate civic act.1 Whether a “weapon of the weak” used by the otherwise silenced population, a tool by the regime -

The Marshall Plan and the Cold War ______

Background Essay: The Marshall Plan and the Cold War _____________________________________________ The Cold War was fought with words and threats rather than violent action. The two nations at war were the United States and the Soviet Union. Although the two superpowers had worked as allies to defeat Germany during World War II, tensions between them grew after the war. Feelings of mistrust and resentment began to form as early as the 1945 Potsdam Conference, where Harry S. Truman and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin met. Stalin was interested in expanding Russia’s power into Eastern Europe, and the U.S. feared that Russia was planning to take over the world and spread the political idea of Communism. Truman’s response to the Soviet Union’s sphere of influence and current conditions of war-torn Europe would become known as the Truman Doctrine. This doctrine proposed to give aid to countries that were suffering from the aftermath of World War II and threatened by Soviet oppression. The U.S. was especially concerned about Greece and Turkey. Due to the slow progress of Europe’s economic development following WWII, Truman devised another plan to offer aid called the Marshall Plan. The plan was named after Secretary of State George Marshall due to Truman’s respect for his military achievements. Truman hoped that by enacting the Marshall Plan two main goals would be accomplished. These goals were: 1.) It would lead to the recovery of production abroad, which was essential both to a vigorous democracy and to a peace founded on democracy and freedom, and which, in the eyes of the United States, the Soviet Union had thus far prevented. -

American Tourism to the Eastern Bloc, 1960-1975

Seeing Red: American Tourism to the Eastern Bloc, 1960-1975 A Thesis Presented to the Academic Faculty by Kayleigh Georgina Haskin In Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Requirements for the Bachelor of Science in History, Technology, and Society with the Research Option Georgia Institute of Technology May 2018 Acknowledgements I am extremely grateful to everyone who played a large or small role in the completion of this project. I would especially like to thank Dr. Kate Pride Brown, my research mentor, for all of her encouragement and guidance during this project; Dr. Laura Bier for being a flexible second-reader; Dr. Tobias Wilson-Bates for his detailed and constructive comments on the drafts I submitted; Kayla McManus-Viana for her enthusiasm and willingness to help edit, even during finals week; and finally, I would like to thank my parents for all of their inspiration and support over the past twenty years. Abstract Theoretical literature asserts that tourism should lead to better interactions between nations with different ideas and cultures. However, empirical studies find that this is often not the case, and certain pre-trip factors are more influential in changing tourists’ opinions than the experience itself. This study examines one of these potential factors: the role that the news media plays in shaping public opinion about foreign countries prior to travel. Using a case study of American tourists to the Eastern Bloc from 1960-1975, this paper suggests that media portrayal contributed to the negative views Americans held of the Soviet Union and the lack of opinion change after travel. -

The Folklore of Deported Lithuanians Essay by Vsevolod Bashkuev

dislocating literature 15 Illustration: Moa Thelander Moa Illustration: Songs from Siberia The folklore of deported Lithuanians essay by Vsevolod Bashkuev he deportation of populations in the Soviet Union oblast, and the Buryat-Mongolian Autonomous Soviet Social- accommodation-sharing program. Whatever the housing ar- during Stalin’s rule was a devious form of political ist Republic. A year later, in March, April, and May 1949, in rangements, the exiles were in permanent contact with the reprisal, combining retribution (punishment for the wake of Operation Priboi, another 9,633 families, 32,735 local population, working side by side with them at the facto- being disloyal to the regime), elements of social people, were deported from their homeland to remote parts ries and collective farms and engaging in barter; the children engineering (estrangement from the native cultural environ- of the Soviet Union.2 of both exiled and local residents went to the same schools ment and indoctrination in Soviet ideology), and geopolitical The deported Lithuanians were settled in remote regions and attended the same clubs and cultural events. Sometimes imperatives (relocation of disloyal populations away from of the USSR that were suffering from serious labor shortages. mixed marriages were contracted between the exiles and the vulnerable borders). The deportation operations were ac- Typically, applications to hire “new human resources” for local population. companied by the “special settlement” of sparsely populated their production facilities were -

Remembering George Kennan Does Not Mean Idolizing Him

UNITED STATES InsTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Melvyn P. Leffler This report originated while Melvyn P. Leffler was a Jennings Randolph Fellow at the United States Institute of Peace. He was writing his book on what appeared to be the most intractable and ominous conflict of the post–World War II era—the Cold War. He was addressing the questions of why the Cold War lasted as long as it did and why it ended when Remembering it did. As part of the ongoing dialogue at the United States Institute of Peace, he was repeatedly asked about the lessons of the Cold War for our contemporary problems. George Kennan His attention was drawn to the career of George F. Kennan, the father of containment. Kennan was a rather obscure and frustrated foreign service officer at the U.S. embassy in Lessons for Today? Moscow when his “Long Telegram” of February 1946 gained the attention of policymakers in Washington and transformed his career. Leffler reviews Kennan’s legacy and ponders the implications of his thinking for the contemporary era. Is it Summary possible, Leffler wonders, to reconcile Kennan’s legacy with the newfound emphasis on a “democratic peace”? • Kennan’s thinking and policy prescriptions evolved quickly from the time he wrote the Melvyn P. Leffler, a former senior fellow at the United States “Long Telegram” in February 1946 until the time he delivered the Walgreen Lectures Institute of Peace, won the Bancroft Prize for his book at the University of Chicago in 1950. -

Leps A. Soviet Power Still Thrives in Estonia

Leps A. ♦ The Soviet power still thrives in Estonia Abstract: It is a historical fact that world powers rule on the fate of small countries. Under process of privatization in the wake of the newly regained independence of Estonia in 1991, a new Estonian elite emerged, who used to be managers of ministries, industries, collective farms and soviet farms. They were in a position to privatize the industrial and agricultural enterprises and they quite naturally became the crème de la crème of the Estonian people, having a lot of power and influence because they had money, knowledge, or special skills. They became capitalists, while the status of the Soviet-time salaried workers remained vastly unchanged: now they just had to report to the nouveaux riches, who instituted the principles of pre-voting (a run-up to the election proper) and electronic voting, to be able to consolidate their gains. However those principles are concepts, unknown to the basic law (Constitution) of the Republic of Estonia – hence the last elections of the 13th composition of the Parliament held in 2015 are null and void ab initio. Keywords: elite of the Republic of Estonia; deportation; „every kitchen maid can govern the state“; industry; agriculture; banking; privatisation; basic law of the Republic of Estonia (Constitution); pre-voting; electronic voting. How they did the Republic of Estonia in It is a very sad story in a nutshell, evolving from 1939, when events and changes started to happen in Europe, having important effects on Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania that couldn’t be stopped. Two major European powers - Germany and the Soviet Union reared their ugly heads and, as had invariably happened in the past, took to deciding on destiny of the small states. -

Purifying National Historical Narratives in Russia

A Trial in Absentia: Purifying National Historical Narratives in Russia Author(s): Olga Bertelsen Source: Kyiv-Mohyla Humanities Journal 3 (2016): 57–87 Published by: National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy http://kmhj.ukma.edu.ua/ A Trial in Absentia: Purifying National Historical Narratives in Russia1 Olga Bertelsen Columbia University, Harriman Institute Abstract This study explores contemporary Russian memory politics, and analyzes the ideological underpinnings of the 2011 Moscow court verdict that criminalized a Ukrainian scholarly publication, accusing it of inciting ethnic, racial, national, social, and religious hatred. This accusation is examined in the context of Russia’s attempts to control the official historical narrative. Special attention is paid to the role of Russian cultural and democratic civic institutions, such as the Moscow library of Ukrainian literature and Memorial, in the micro- history of this publication. Deconstructing the judicial reaction of Russian lawmakers toward the Ukrainian publication, the study analyzes the Russian political elite’s attitudes toward the “Ukrainian” historical interpretations of Stalin’s terror and other aspects of common Soviet history, and demonstrates the interconnectedness of the preceding Soviet and modern Russian methods of control over education, history, and culture. Language and legislation play an important role in Russian memory politics that shape the popular historical imagination and camouflage the authoritarian methods of governing in Russia. The case of the Ukrainian -

The Militarization of the Russian Elite Under Putin What We Know, What We Think We Know (But Don’T), and What We Need to Know

Problems of Post-Communism, vol. 65, no. 4, 2018, 221–232 Copyright © 2018 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 1075-8216 (print)/1557-783X (online) DOI: 10.1080/10758216.2017.1295812 The Militarization of the Russian Elite under Putin What We Know, What We Think We Know (but Don’t), and What We Need to Know David W. Rivera and Sharon Werning Rivera Department of Government, Hamilton College, Clinton, NY This article reviews the vast literature on Russia’s transformation into a “militocracy”—a state in which individuals with career experience in Russia’s various force structures occupy important positions throughout the polity and economy—during the reign of former KGB lieutenant colonel Vladimir Putin. We show that (1) elite militarization has been extensively utilized both to describe and explain core features of Russian foreign and domestic policy; and (2) notwithstanding its widespread usage, the militocracy framework rests on a rather thin, and in some cases flawed, body of empirical research. We close by discussing the remaining research agenda on this subject and listing several alternative theoretical frameworks to which journalists and policymakers arguably should pay equal or greater attention. In analyses of Russia since Vladimir Putin came to I was an officer for almost twenty years. And this is my own power at the start of the millennium, this master narrative milieu.… I relate to individuals from the security organs, from the Ministry of Defense, or from the special services as has been replaced by an entirely different set of themes. ’ if I were a member of this collective. —Vladimir Putin One such theme is Putin s successful campaign to remove (“Dovol’stvie voennykh vyrastet v razy” 2011) the oligarchs from high politics (via prison sentences, if necessary) and renationalize key components of the nat- In the 1990s, scholarly and journalistic analyses of Russia ural resource sector.