Murder Ballads.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies Teaching English Language and Literature for Secondary Schools Petr Husseini Nick Cave’s Lyrics in Official and Amateur Czech Translations Master‟s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Renata Kamenická, Ph.D. 2009 Declaration I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. .................................................. Author‟s signature 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Mgr. Renata Kamenická, Ph.D., for her kind help, support and valuable advice. 3 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 5 1. Translation of Lyrics and Poetry .............................................................................. 9 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................... 9 1.2 General Nature of Lyrics and Poetry ........................................................ 11 1.3 Tradition of Lyrics Translated into Czech ............................................... 17 1.4 Conclusion ................................................................................................... 20 2. Nick Cave’s Lyrics in King Ink and King Ink II ................................................... 22 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................. 22 -

Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds Till Ericsson Globe

2017-02-07 11:37 CET Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds till Ericsson Globe Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds återvänder till Sverige. Denna gång är det Stockholm och Ericsson Globe som står värd när ett av vår tids mest kritikerhyllade band kommer på efterlängtat besök den 18 oktober. Biljetterna släpps fredagen den 17 februari kl 10.00. Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds har sålt över 5 miljoner album och deras sound har påverkat och inspirerat tusentals artister och fans världen över. I september förra året släpptes deras femtonde album ”Skeleton Tree” – dagen efter den tunga och vackra dokumentären ”One More Time With Feeling”, om bandets arbete med albumet hade premiär. Albumet gick in på albumlistans förstaplats i åtta länder, och topp-5-placeringar i ytterligare elva länder. Albumet blev bandets största listframgång i både England (2) och i USA (27). När bandet nu äntligen kommer till Sverige i höstmörkret består de av Nick Cave, Warren Ellis, Martyn Casey, Thomas Wydler, Jim Sclavunos, Conway Savage, George Vjestica och Larry Mullins. Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds i Ericsson Globe - detta vill man inte missa. Datum 18.10 - Ericsson Globe, Stockholm Biljetter Biljetterna kostar 495-850 kr + serviceavgift och säljs via www.LiveNation.se, www.AXS.com samt Stockholm Lives biljettkassa 0771 31 00 00 Live Nation är Sveriges största arrangör av konserter, turnéer och evenemang. Varje år har vi via över 2000 evenemang äran att få vara med och ge över en miljon svenskar den unika upplevelse som endast livemusik och liveunderhållning kan ge – musik är allra bäst live. Vi producerar det mesta från mindre klubbspelningar via riksomfattande turnéer och stora utomhuskonserter till turnéer med våra svenska artister utomlands. -

A Message to MTV

textploitationtefl A message to MTV Do you know anything about these people? What do you think they might do? (try to use some of the language below) Target language He might be / she could be … He looks like a … I guess she is probably a … They both look as if they are … Listening 1 – Gist Listen and answer the following questions 1. Who is the letter to? 2. What is the letter about? 3. What is he grateful for? 4. What does the writer ask for? 5. What does the writer say he feels unhappy with? Listening 2 – Vocab building Which words complete these phrases? Listen to check nominations I have ________ feel more ________ with ________ appreciated I have always been of the ________ my ________ thanks at the ________ of times ________ said that, glittering ________ textploitationtefl Listening 3 - Attitude Listen again and decide how you think the reader, Kylie, feels about the letter? a) Serious c) Amused b) Concerned d) Happy Reflection What do you think of this decision? Why might other musicians want to take part in awards shows and ceremonies? Should the arts in general be evaluated by competition and prizes? (why/why not) Writing "My muse is not a horse and I am in no horse race." 1. What is the register of the letter you have just heard, formal or informal? Why? 2. Now read the letter on the next page, are there any words which would be typically formal? _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ 3. What typical features of a formal letter are there in this letter? 4. -

Special Issue

ISSUE 750 / 19 OCTOBER 2017 15 TOP 5 MUST-READ ARTICLES record of the week } Post Malone scored Leave A Light On Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 with “sneaky” Tom Walker YouTube scheme. Relentless Records (Fader) out now Tom Walker is enjoying a meteoric rise. His new single Leave } Spotify moves A Light On, released last Friday, is a brilliant emotional piano to formalise pitch led song which builds to a crescendo of skittering drums and process for slots in pitched-up synths. Co-written and produced by Steve Mac 1 as part of the Brit List. Streaming support is big too, with top CONTENTS its Browse section. (Ed Sheeran, Clean Bandit, P!nk, Rita Ora, Liam Payne), we placement on Spotify, Apple and others helping to generate (MusicAlly) love the deliberate sense of space and depth within the mix over 50 million plays across his repertoire so far. Active on which allows Tom’s powerful vocals to resonate with strength. the road, he is currently supporting The Script in the US and P2 Editorial: Paul Scaife, } Universal Music Support for the Glasgow-born, Manchester-raised singer has will embark on an eight date UK headline tour next month RotD at 15 years announces been building all year with TV performances at Glastonbury including a London show at The Garage on 29 November P8 Special feature: ‘accelerator Treehouse on BBC2 and on the Today Show in the US. before hotfooting across Europe with Hurts. With the quality Happy Birthday engagement network’. Recent press includes Sunday Times Culture “Breaking Act”, of this single, Tom’s on the edge of the big time and we’re Record of the Day! (PRNewswire) The Sun (Bizarre), Pigeons & Planes, Clash, Shortlist and certain to see him in the mix for Brits Critics’ Choice for 2018. -

The Story of Sonny Boy Slim

THE STORY OF SONNY BOY SLIM Ever since 2010, when Gary Clark Jr. wowed audiences with electrifying live sets everywhere from the Crossroads Festival to Hollywood’s historic Hotel Café, his modus operandi has remained crystal clear: “I listen to everything…so I want to play everything.” The revelation that is the Austin-born virtuoso guitarist, vocalist and songwriter finds him just as much an amalgamation of his myriad influences and inspirations. Anyone who gravitated towards Clark’s, 2011’s Bright Lights EP, heard both the evolution of rock and roll and a savior of blues. The following year’s full-length debut, Blak And Blu, illuminated Clark’s vast spectrum - “Please Come Home” is reminiscent of Smokey Robinson, while “Ain’t Messin’ Around” recalls Sly and the Family Stone. 2014’s double disc Gary Clark Jr–Live projected Clark into 3D by adding palpable dimension and transcendent power –– songs soared and drifted from the epic, psychedelic-blues of “When My Train Comes In” to his anthemic, hip-hop, rock-crunch calling card, “Bright Lights”, all the way down to the deep, dark, muddy water of “When The Sun Goes Down”. There are a handful of folks who have informed for the mélange of genres and styles, which comprise the genius of Clark. One is Michael Jackson. It was on Denver stop of MJ’s Bad Tour where a four-year-old Gary’s life was altered after witnessing The King of Pop. By the sixth grade, Clark would own his first set of strings (Ibanez RX20). As a teen, Clark began making a local name by jamming with adult musicians around nearby clubs. -

Full Results of Survey of Songs

Existential Songs Full results Supplementary material for Mick Cooper’s Existential psychotherapy and counselling: Contributions to a pluralistic practice (Sage, 2015), Appendix. One of the great strengths of existential philosophy is that it stretches far beyond psychotherapy and counselling; into art, literature and many other forms of popular culture. This means that there are many – including films, novels and songs that convey the key messages of existentialism. These may be useful for trainees of existential therapy, and also as recommendations for clients to deepen an understanding of this way of seeing the world. In order to identify the most helpful resources, an online survey was conducted in the summer of 2014 to identify the key existential films, books and novels. Invites were sent out via email to existential training institutes and societies, and through social media. Participants were invited to nominate up to three of each art media that ‘most strongly communicate the core messages of existentialism’. In total, 119 people took part in the survey (i.e., gave one or more response). Approximately half were female (n = 57) and half were male (n = 56), with one of other gender. The average age was 47 years old (range 26–89). The participants were primarily distributed across the UK (n = 37), continental Europe (n = 34), North America (n = 24), Australia (n = 15) and Asia (n = 6). Around 90% of the respondents were either qualified therapists (n = 78) or in training (n = 26). Of these, around two-thirds (n = 69) considered themselves existential therapists, and one third (n = 32) did not. There were 235 nominations for the key existential song, with enormous variation across the different respondents. -

THE CALLAS: Athenian Psych-Post-Punks Prepare New Album in Collaboration with Sonic Youth's Lee Ranaldo | Dirty Water Records

The Callas With Lee Ranaldo Jun 19, 2018 10:11 BST THE CALLAS: Athenian Psych-Post-Punks Prepare New Album in Collaboration with Sonic Youth's Lee Ranaldo | Dirty Water Records Promo Access THE CALLASis the tip of an artistic squad producing music, artworks, films, magazines, events, art shows, initiated by the brothers Lakis & Aris Ionas. The group worked with Lee Ranaldoon the soundtrack of their new feature film “The Great Eastern” and on their new full-length album, “Trouble and Desire” which is due for release on October, 26th 2018 on Inner Ear and Dirty Water Records. Their last two albums, "Am I Vertical?” and “Half Kiss, Half Pain" were produced byJim Sclavunos (Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds, Lydia Lunch, The Cramps). “As multi-media artists and filmmakers, they approach music making from a very different perspective than the average musician and come up with some quite unexpected results,” says Sclavunos. “ The sonic palette of the new album is diverse and exploratory, with songs that range in style from dreamy subversive pop to brutal post-punk skronk to deconstructed rebetiko.” Watch video on YouTube here Lee Ranaldo described his experience on collaborating with the Callas: “It’s been a pleasure for me to know and collaborate with The Callas on their new album Trouble and Desire - we met a few years ago and I’ve been drawn into their artistic world in Athens. I’m a fan of their visual art tapestries and their art studio/venue and I’ve been having a great time making music with these like-minded travelers. -

Olivia Rodrigo's 'Sour' Returns to No. 1 on Billboard 200 Albums Chart

Bulletin YOUR DAILY ENTERTAINMENT NEWS UPDATE JUNE 28, 2021 Page 1 of 24 INSIDE Olivia Rodrigo’s ‘Sour’ Returns to • BTS’ ‘Butter’ Leads Hot 100 for Fifth No. 1 on Billboard 200 Albums Chart Week, Dua Lipa’s ‘Levitating’ Becomes BY KEITH CAULFIELD Most-Heard Radio Hit livia Rodrigo’s Sour returns to No. 1 on five frames (charts dated Jan. 23 – Feb. 20). (It’s worth • Executive of the the Billboard 200 chart for a second total noting that Dangerous had 30 tracks aiding its SEA Week: Motown Records Chairman/ week, as the album steps 3-1 in its fifth and TEA units, while Sour only has 11.) CEO Ethiopia week on the list. It earned 105,000 equiva- Polo G’s Hall of Fame falls 1-2 in its second week Habtemariam Olent album units in the U.S. in the week ending June on the Billboard 200 with 65,000 equivalent album 24 (down 14%), according to MRC Data. The album units (down 54%). Lil Baby and Lil Durk’s former • Will Avatars Kill The Radio Stars? debuted at No. 1 on the chart dated June 5. leader The Voice of the Heroes former rises 4-3 with Inside Today’s Virtual The Billboard 200 chart ranks the most popular 57,000 (down 21%). Migos’ Culture III dips 2-4 with Artist Record Labels albums of the week in the U.S. based on multi-metric 54,000 units (down 58%). Wallen’s Dangerous: The consumption as measured in equivalent album units. Double Album is a non-mover at No. -

Dr. Richard Brown Faith, Selfhood and the Blues in the Lyrics of Nick Cave

Student ID: XXXXXX ENGL3372: Dissertation Supervisor: Dr. Richard Brown Faith, Selfhood and the Blues in the Lyrics of Nick Cave Table of Contents Introduction 2 Chapter One – ‘I went on down the road’: Cave and the holy blues 4 Chapter Two – ‘I got the abattoir blues’: Cave and the contemporary 15 Chapter Three – ‘Can you feel my heart beat?’: Cave and redemptive feeling 25 Conclusion 38 Bibliography 39 Appendix 44 Student ID: ENGL3372: Dissertation 12 May 2014 Faith, Selfhood and the Blues in the lyrics of Nick Cave Supervisor: Dr. Richard Brown INTRODUCTION And I only am escaped to tell thee. So runs the epigraph, taken from the Biblical book of Job, to the Australian songwriter Nick Cave’s collected lyrics.1 Using such a quotation invites anyone who listens to Cave’s songs to see them as instructive addresses, a feeling compounded by an on-record intensity matched by few in the history of popular music. From his earliest work in the late 1970s with his bands The Boys Next Door and The Birthday Party up to his most recent releases with long- time collaborators The Bad Seeds, it appears that he is intent on spreading some sort of message. This essay charts how Cave’s songs, which as Robert Eaglestone notes take religion as ‘a primary discourse that structures and shapes others’,2 consistently use the blues as a platform from which to deliver his dispatches. The first chapter draws particularly on recent writing by Andrew Warnes and Adam Gussow to elucidate why Cave’s earlier songs have the blues and his Christian faith dovetailing so frequently. -

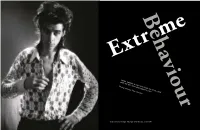

Laura Harker & Paul Sullivan on Nick Cave and the 80S East

Behaviour 11 Extr me LaurA HArKer & PAul SullIvAn On Nick CAve AnD THe 80S East KreuzBerg SCene Photography by Peter gruchot 10 ecords), 24 April 1986 Studio session for the single ‘The Singer’ (Mute r Cutting a discreet diagonal between Kottbusser Tor and Oranienplatz, Dresdener Straße is one of the streets that provides blissful respite from east Kreuzberg’s constant hustle and bustle. Here, the noise of the traffic recedes and the street’s charms surge subtly into focus: fashion boutiques and indie cafés tucked into the ground floors of 19th Century Altbauten, the elegantly run-down Kino Babylon and the dark and seductive cocktail bar Würgeengel, the “exterminating angel”, a name borrowed from a surrealist film by luis Buñuel. It all looked very different in the 80s of course, when the Berlin Wall stood just under a kilometre away and the façades of these houses – now expensively renovated and worth a pretty penny – were still pockmarked by World War Two bulletholes. Mostly devoid of baths, the interiors heated by coal, their inhabitants – mostly Turkish immigrants – shivered and shuffled their way through the Berlin winter. 12 13 It was during this pre-Wende milieu that a tall, skinny and largely unknown Australian musician named Nicholas Edward Cave moved into no. 11. Aside from brief spells in apartments on naumannstraße (Schöneberg), yorckstraße, and nearby Oranienstraße, Cave spent the bulk of his seven on-and-off years in Berlin living in a tiny apartment alongside filmmaker and musician Christoph Dreher, founder of local outfit Die Haut. It was in this house that Cave wrote the lyrics and music for several Birthday Party and Bad Seeds albums, penned his debut novel (And The Ass Saw The Angel) and wielded a sizeable influence over Kreuzberg’s burgeoning post-punk scene. -

Nick Cave Anthology Free

FREE NICK CAVE ANTHOLOGY PDF Nick Cave | 128 pages | 24 Aug 2001 | Music Sales Ltd | 9780711986817 | English | London, United Kingdom Read Download Nick Cave Anthology PDF – PDF Download Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want Nick Cave Anthology read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Nick Cave Anthology editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try Nick Cave Anthology. Open Preview See a Problem? Details Nick Cave Anthology other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return Nick Cave Anthology Book Page. Preview — Anthology by Nick Cave. Anthology by Nick Cave. Since the late seventies, Nick Cave has continually reaffirmed his position as one of the greatest Australian songwriters, rock musicians and Nick Cave Anthology of all time. This terrific anthology represents some of his his best moments including his time with the Bad Seeds as well as solo collaborations. This volume contains Piano, Vocal and Guitar arrangements of eighteen classic Since the late seventies, Nick Cave Anthology Cave has continually reaffirmed his position as one of the greatest Australian songwriters, rock musicians and authors of all time. This volume contains Piano, Vocal and Guitar arrangements of eighteen classic songs by Nick Cave, with full lyrics. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Original Title. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Anthologyplease sign up. Lists with This Book. This book is not Nick Cave Anthology featured on Listopia. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 4. Rating details. All Languages. More filters. -

Music on Screen

Music on Screen From Cinema Screens to Touchscreens Part I Edited by Sarah Hall James B. Williams Musicology Research Issue 2 Spring 2017 This page is left intentionally blank. Music on Screen From Cinema Screens to Touchscreens Part I Edited by Sarah Hall James B. Williams Musicology Research Issue 2 Spring 2017 MusicologyResearch The New Generation of Research in Music Spring 2017 © MusicologyResearch No part of this text, including its cover image, may be reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form by any electronic, mechanical, or others means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from MusicologyResearch and its contributors. MusicologyResearch offers a model whereby the authors retain the copyright of their contributions. Cover Image ‘Supreme’. Contemporary Abstract Painting, Acrylic, 2014. Used with permission by artist Elizabeth Chapman. © Elizabeth Chapman. http://melizabethchapman.artspan.com http://melizabethchapman.blogspot.co.uk Visit the MusicologyResearch website at http://www.musicologyresearch.co.uk for this issue http://www.musicologyresearch.co.uk/publications/ingridbols-programmingscreenmusic http://www.musicologyresearch.co.uk/publications/pippinbongiovanni-8-bitnostalgiaandhollywoodglamour http://www.musicologyresearch.co.uk/publications/emaeyakpetersylvanus-scoringwithoutscorsese http://www.musicologyresearch.co.uk/publications/salvatoremorra-thetunisianudinscreen http://www.musicologyresearch.co.uk/publications/andrewsimmons-giacchinoasstoryteller