The Fan Area Historic District CONTENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Follow in Lincoln's Footsteps in Virginia

FOLLOW IN LINCOLN’S FOOTSTEPS IN VIRGINIA A 5 Day tour of Virginia that follows in Lincoln’s footsteps as he traveled through Central Virginia. Day One • Begin your journey at the Winchester-Frederick County Visitor Center housing the Civil War Orientation Center for the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields National Historic District. Become familiar with the onsite interpretations that walk visitors through the stages of the local battles. • Travel to Stonewall Jackson’s Headquarters. Located in a quiet residential area, this Victorian house is where Jackson spent the winter of 1861-62 and planned his famous Valley Campaign. • Enjoy lunch at The Wayside Inn – serving travelers since 1797, meals are served in eight antique filled rooms and feature authentic Colonial favorites. During the Civil War, soldiers from both the North and South frequented the Wayside Inn in search of refuge and friendship. Serving both sides in this devastating conflict, the Inn offered comfort to all who came and thus was spared the ravages of the war, even though Stonewall Jackson’s famous Valley Campaign swept past only a few miles away. • Tour Belle Grove Plantation. Civil War activity here culminated in the Battle of Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864 when Gen. Sheridan’s counterattack ended the Valley Campaign in favor of the Northern forces. The mansion served as Union headquarters. • Continue to Lexington where we’ll overnight and enjoy dinner in a local restaurant. Day Two • Meet our guide in Lexington and tour the Virginia Military Institute (VMI). The VMI Museum presents a history of the Institute and the nation as told through the lives and services of VMI Alumni and faculty. -

Nomination Form Date Entered See Instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type All Entries-Complete Applicable Sections 1

OM6 No.1024-0018 Erp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory-Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries-complete applicable sections 1. Name hlstortc BRANCH HOUSE (VHLC File 6127-246) -- ----- - - and or common Same 2. Location 8 number 2501 Monument Avenue - N/Anot for publication city, town Richmond Fk4\ vicinity of stale Virginia code 5 1 county (in city) code 750 3.- Classification- - ~~ Category Ownership Status Present Use -district -public X occupied agriculture -museum X building@) X private unoccupied _.X_ commercial - _park -structure -both -work in progress -educational -private residence -site Public Acquisition Accessible -entertainment -.religious -object - in process x yes: restricted -governmani -scientific being considered yes: unrestricted -industrial -transportation TA -no -military -other: 4. Owner of Property name Robert E. and Janice W. Pogue street & number 3902 Sulgrave Ibad Virginia 23221 city, town N/Avicinity of state -- -- 5. Location of Leaal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Richmond City Hall Tax Assessor's Off ice street & number 900 East Broad Street - city, town Richmond state Virginia 23219 6. Representation in Existing $urveys(see continuation Sheet iil) (I) Monument Avenue HlstOrlc ulstrlct titleFile 11127-174 has this properly been determined eligible? -yes -noX - X 1969 -federal slate county .- local date ---- - --.-- 221 Governor Street depository for survey records -- - -. -- - - - Richmond Virginia 23219 state city, town -- . - 7. Description Condition Check one Check one _X excellent -deteriorated & unaltered -L original site -good -ruins -altered -moved date -..-.___--p-N/ A A fair -unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance SUMMARY DESCRIPTION The Branch House at 2501 Monument Avenue is situated on the southeast corner of Monument Avenue and Davis Street in the Fan District of Richmond. -

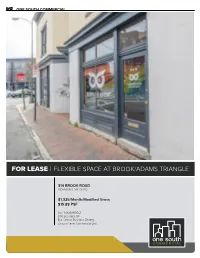

For Lease | Flexible Space at Brook/Adams Triangle

ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL FOR LEASE | FLEXIBLE SPACE AT BROOK/ADAMS TRIANGLE 314 BROOK ROAD RICHMOND, VA 23220 $1,325/Month/Modified Gross $19.88 PSF PID: N0000119012 800 Leasable SF B-4 Central Business Zoning Ground Level Commercial Unit PETERSBURG[1] MULTIFAMILY PORTFOLIO Downtown Arts District Storefront A perfect opportunity located right in the heart of the Brook/Adams Road triangle! This beautiful street level retail storefront boasts high ceilings, hardwood floors, exposed brick walls, and an expansive street-facing glass line. With flexible use options, this space could be a photographer studio, a small retail maker space, or the office of a local tech consulting firm. An unquestionable player in the rise of Broad Street’s revitalization efforts underway, this walkable neighborhood synergy includes such residents as Max’s on Broad, Saison, Cite Design, Rosewood Clothing Co., Little Nomad, Nama, and Gallery5. Come be a part of the creative community that is transforming Richmond’s Arts District and meet the RVA market at street level. Highlights Include: • Hardwood Floors • Exposed Brick • Restroom • Janitorial Closet • Basement Storage • Alternate Exterior Entrance ADDRESS | 314 Brook Rd PID | N0000119012 STREET LEVEL BASEMENT STOREFRONT STORAGE ZONING | B-4 Central Business LEASABLE AREA | 800 SF LOCATION | Street Level STORAGE | Basement PRICE | $1,325/Mo/Modified Gross 800 SF HISTORIC LEASABLE SPACE 1912 CONSTRUCTION PRICE | $19.88 PSF *Information provided deemed reliable but not guaranteed 314 BROOK RD | RICHMOND VA 314 BROOK RD | RICHMOND VA DOWNTOWN ARTS DISTRICT AREA FAN DISTRICT JACKSON WARD MONROE PARK 314 BROOK RD VCU MONROE CAMPUS RICHMOND CONVENTION CTR THE JEFFERSON BROAD STREET MONROE WARD RANDOLPH MAIN STREET VCU MED CENTER CARY STREET OREGON HILL CAPITOL SQUARE HOLLYWOOD CEMETERY DOWNTOWN RICHMOND CHURCH HILL ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL TEAM ANN SCHWEITZER RILEY [email protected] 804.723.0446 1821 E MAIN STREET | RICHMOND VA ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL 2314 West Main Street | Richmond VA 23220 | onesouthcommercial.com | 804.353.0009 . -

Fan District 24 Unit Multifamily

ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL DRAFT 607 E BROADWAY FOR SALE | FAN DISTRICT 24 UNIT MULTIFAMILY 2700 IDLEWOOD AVE RICHMOND, VA 23220 $3,600,000 PID: W0001198007 7,500 SF Parcel 13,095 SF Building Area 3,273 SF Basement Area 3 Stories 24 Residential Units R-63 Multifamily Urban Zoning 1912 Construction PETERSBURG[1] MULTIFAMILY PORTFOLIO TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 PROPERTY SUMMARY 4 PHOTOS 7 PROPERTY SURVEY R-63 MULTIFAMILY 8 FLOOR PLANS URBAN ZONING 11 SALES COMPARABLES 12 RICHMOND’S FAN DISTRICT 13 DEMOGRAPHICS & MARKET DATA 7,500 SF 14 MULTIFAMILY MARKET ANALYSIS PARCEL AREA 15 LOCATION MAP 16 ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL TEAM 13,095 SF BUILDING AREA 3,273 SF BASEMENT Communication: One South Commercial is the exclusive representative of Seller in its disposition of 2700 Idlewood Ave. All communications regarding the property should be directed to the One South Commercial listing team. 24 RESIDENTIAL Property Tours: UNITS Prospective purchasers should contact the listing team regarding property tours. Please provide at least 72 hours advance notice when requesting a tour date out of consideration for current residents. Offers: Offers should be submitted via email to the listing team in the form of a non- binding letter of intent and should include: 1) Purchase Price; 2) Earnest Money Deposit; 3) Due Diligence and Closing Periods. 1912 HISTORIC Disclaimer: CONSTRUCTION This offering memorandum is intended as a reference for prospective purchasers in the evaluation of the property and its suitability for investment. Neither One South Commercial nor Seller make any representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the materials contained in the offering memorandum. -

Human Rights, Collective Memory, and Counter Memory: Unpacking the Meaning of Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia Melanie L

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Art Education Publications Dept. of Art Education 2011 Human Rights, Collective Memory, and Counter Memory: Unpacking the Meaning of Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia Melanie L. Buffington Virginia Commonwealth University, [email protected] Erin Waldner Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/arte_pubs Part of the Art Education Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Social Policy Commons Copyright © 2011 Journal of Cultural Research in Art Education Downloaded from http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/arte_pubs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Dept. of Art Education at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art Education Publications by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Human Rights, Collective Memory,' and Counter Memory: Unpacking the Meaning of Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia M ELANIE L. BUFFI" GTO'l ' ''D ERI" W ALD " ER ABSTRACT Th is article addresses human rights issues of the built environment via the presence of monuments in publi c places. Because of their prominence, monuments and publi c art can offer teachers and students many opportunit ies for interdiscip li nary study that directly relates to the history of their location Through an exploration of the ideas of co llective memory and counter memory, t his articl e explores the spec ific example of Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia, Further; the aut hors investigate differences in t he ways monu ments may be understood at the time they were erected versus how they are understood in the present. -

Final Project Report Boulevard Diamond Stadium Highest & Best Use Analysis

Final Project Report Boulevard Diamond Stadium Highest & Best Use Analysis Prepared for The City of Richmond Richmond, VA Submitted by Economics Research Associates Davenport & Company LLC Chmura Economics & Analytics September 2008 ERA Project No. 17889 1101 Connecticut Avenue, NW Suite 750 Washington, DC 20036 202.496.9870 FAX 202.496.9877 www.econres.com Los Angeles San Francisco San Diego Chicago Washington DC London New York Table of Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 5 Executive Summary......................................................................................................................... 5 Key Findings ................................................................................................................................... 6 Discussion of Key Items & Assumptions...........................................................................................9 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................... 10 II. Methodology and Approach ...................................................................................... 13 Boulevard and Shockoe Bottom Site Considerations ...................................................................... 13 Land Planning Assumptions.......................................................................................................... 17 Market Demand Assumptions.......................................................................................................18 -

Confederate Monument REMIX"

Proposal for: Intent to Acquire Civil War Monument AKA: "Confederate Monument REMIX" City of Richmond, VA Richmond City Counsel Notice: Richmond City Council News Release, AuGust 17, 2020 Ord. No. 2020-154 DARNstudio 18 Forest Farm Drive Roxbury, CT 06783 www.DARNstudio.com 917.482.1142 CONFEDERATE MONUMENT REMIX SEPTEMBER 2020 1. LETTER OF INTENT September 8, 2020 Richmond City Council Richmond City Hall 900 E. Broad Street, Suite 305 Richmond, Virginia 23219 USA 804.646.2778 (tel) Attn: RE: Proposal to Acquire Civil War Monument September 8, 2020 Dear Chairperson, We are pleased to present our proposal for the City of Richmond's Civil War Monument DeaccessioninG Request. DARNstudio is a collaboration of artists David Anthone and Ron Norsworthy. Our work investigates the built, designed, or otherwise manifested world we live in, breaks down its components and uncouples them from their implicit and inherited meaninG(s). We then re- assemble in a way that disrupts its original function. Our work encourages alternative ways of understanding objects, ideas and structures through a process we refer to as “re:meaning” ThrouGh reassiGnment, remixinG, inversion, or juxtaposition DARNstudio’s work examines the purpose of things. These things may range from the macro and intangible (cultural institutions and norms) to the micro and concrete (mundane objects, words, expressions or phrases). We glean new meanings from these things in their disrupted reconfigurations which triggers new dialogue on the commonplace, the happenstance, and the “extraordinary ordinary”. Our Goal is to cast the familiar in an unexpected context so that it can be seen in an unfamiliar and new way. -

For Sale | Broad St Arts District Mixed Use

ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL DRAFT 607 E BROADWAY FOR SALE | BROAD ST ARTS DISTRICT MIXED USE 24 E BROAD ST RICHMOND, VA 23219 $615,000 PID: N0000076035 0.07 AC Parcel 8,134 SF Building Area 2,362 SF Basement Area 3 Stories B-4 Central Business Zoning 1915 Construction State & Fed Historic Tax Credit Eligible PETERSBURG[1] MULTIFAMILY PORTFOLIO TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 PROPERTY SUMMARY B-4 CENTRAL BUSINESS 4 GROUND LEVEL ZONING 5 SECOND LEVEL 6 THIRD LEVEL 7 EXTERIOR AND BASEMENT 8 RICHMOND METRO OVERVIEW 0.07 AC 10 RICHMOND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PARCEL AREA 11 MAJOR EMPLOYERS 12 DEMOGRAPHICS 13 MULTIFAMILY MARKET ANALYSIS 14 RETAIL MARKET ANALYSIS 8,134 SF BUILDING AREA 15 LOCATION MAP 16 ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL CONTACT 2,632 SF BASEMENT Communication: One South Commercial is the exclusive representative of Seller in its disposition of 24 E Broad St. All communications regarding the property should be directed HISTORIC to the One South Commercial listing team. TAX CREDIT ELIGIBLE Property Tours: Prospective purchasers should contact the listing team regarding property tours. Please provide at least 72 hours advance notice when requesting a tour date out of consideration for current residents. Offers: Offers should be submitted via email to the listing team in the form of a non- binding letter of intent and should include: 1) Purchase Price; 2) Earnest Money Deposit; 3) Due Diligence and Closing Periods. Disclaimer: This offering memorandum is intended as a reference for prospective purchasers in the evaluation of the property and its suitability for investment. Neither One South Commercial nor Seller make any representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the materials contained in the offering memorandum. -

Monument Avenue Historic District Richmond, Virginia ______Aerial View of Monument Ave

18 JuM south (left) of Monument Avenue, Park Avenue traces the htstonc path at the IP,*; ihe old Sydney grid (nou the Fan District) from the avenue precinct Virginia Si.tte ! Monument Avenue Historic District Richmond, Virginia ____________ Aerial view of Monument Ave. looking west ——————————————————— Photo: Sarah Driggs, June 1997 ————— Monument Avenue Historic District I Richmond, Virginia Aerial view of Monument Ave. looking west Photo: Sarah Driggs, June 1997 -k - !1 i ' ' . > •>* n , t \ • '• i; i " • i 1 ,. • i i •• ' i k , 1 kl 1 *• t •* j Uj i ~a K • it «• ' t:i' - : : t ,r.*• "' tf ' "ii ~"'~"m*•> » *j -. '.— 1. .1 - "r r. A ""~«"H "i •«• i' "j —— „ T~ . ~_ ———."•".' ^f T. i_J- Y 22 Somewhat idealized plal of the AJIen Addition, 1888, two ycare before the Monument Avenue Historic District Richmond, Virginia Lee Monument & 1800 Monument Ave., The JefFress House looking northwest Photo: Sarah Driees, June 1997 IT* Monument Avenue Historic District Richmond, Virginia 2314, 2320, & 2324 Monument Ave. looking west Photo: Sarah Driggs, June 1997 ——49Ktta£E£i Monument Avenue Historic District Richmond, Virginia 2200 & 2204 Monument Ave., porches looking west Photo: Sarah Driggs, June 1997 ,, f-ftf? Monument Avenue Historic District Richmond, Virginia Stuart Monument looking northwest Photo: Sarah Driggs, June 1997 Monument Avenue Historic District Richmond, Virginia Stonewall Jackson Monument & 622 North Boulevard looking southwest Photo: Sarah Driees, June 1997 Monument Avenue Historic District Richmond, Virginia Matthew Fontaine Maury Monument & 3101 Monument Ave., the Lord Fairfax Apartments Photo: Sarah Driggs, June 1997 !?*-sf* • •«.« r*x. • • V- ^-SK. ^*-'VlBr v» Monument Avenue Historic District I Richmond, VA Arthur Ashe Monument Photo: Sarah Prises. -

For Sale | Shockoe Bottom Office and Multifamily

ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL FOR SALE | SHOCKOE BOTTOM OFFICE AND MULTIFAMILY 1707 EAST MAIN STREET Richmond VA 23223 $750,000 PID: E0000109004 Ground and Lower Level Office Space 2 Residential Units on Second Level 4,860 SF Office Space B-5 Central Business Zoning Pulse BRT Corridor Location 0.05 AC Parcel Area Opportunity Zone PETERSBURG[1] MULTIFAMILY PORTFOLIO TABLE OF CONTENTS* 3 PROPERTY SUMMARY 4 PHOTOS 2 8 SHOCKOE BOTTOM NEIGHBORHOOD RESIDENTIAL UNITS 10 PULSE CORRIDOR PLAN 11 RICHMOND METRO AREA 12 RICHMOND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OFFICE 13 RICHMOND MAJOR EMPLOYERS 4,860 SF 14 DEMOGRAPHICS 15 ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL TEAM B-5 CENTRAL BUSINESS ZONING OPPORTUNITY ZONE 2008 RENOVATION Communication: One South Commercial is the exclusive representative of Seller in its disposition of the 1707 E Main St. All communications regarding the property should be directed to the One South Commercial listing team. Property Tours: Prospective purchasers should contact the listing team regarding property tours. Please provide at least 72 hours advance notice when requesting a tour date out of consideration for current residents. Offers: Offers should be submitted via email to the listing team in the form of a non- binding letter of intent and should include: 1) Purchase Price; 2) Earnest Money Deposit; 3) Due Diligence and Closing Periods. Disclaimer: This offering memorandum is intended as a reference for prospective purchasers in the evaluation of the property and its suitability for investment. Neither One South Commercial nor Seller make any representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the materials contained in the offering memorandum. -

Fan Overlay District (Fod) Guidelines

FAN OVERLAY DISTRICT (FOD) GUIDELINES I. INTRODUCTION A. Purpose The purpose of these guidelines is to protect and maintain the established historic architectural character of the Fan. The “Guidelines for New Construction” promote existing architectural coherence and harmony by controlling patterns of design and features. The “Guidelines for Demolition” preserve historic structures by managing the demolition process. Also included are “Recommendations for Alterations to Existing Structures.” Though purely aspirational, they are provided as a resource with the hope that they will be adhered to when making exterior alterations and renovations to structures in the Fan. B. Overview of the Fan and its Architecture Richmond’s Fan District is a predominately residential neighborhood of some hundred blocks. Largely built up between the 1890s and the 1920s, the district is an outgrowth of the demand for better housing and improved services by a new, urban middle class who spurred architects, builders, and real estate speculators to develop entire blocks of town houses sprinkled with conveniently located small commercial establishments. Scattered in the neighborhood are several churches, apartment houses, two public schools, and a hospital. The district conveys a unity that depends not so much on consistent architectural style as on intrinsic qualities of good urban design, such as uniform heights and setbacks, compatibility of textures and building materials, and consistent building footprints of mostly three-bay town houses. The Fan District encompasses the Monument Avenue Historic District, the West Grace Street Historic District, and the West Franklin Street Historic District. Each of these areas have been designated a National Historic Landmark and a Richmond Old and Historic District. -

NPS Form 10 900 OMB No. 1024 0018

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property Historic name Three Chopt Road Historic District Other nameslsite VA DHR No. 127-6064 number 2. Location Street & Both sides of a 1.3 mile stretch of Three Chopt Rd from its not for number intersection with Cary St Rd on the south to Bandy Rd on the north. City or Richmond town State zip - Virginia code VA county .- In9endentCity code 760 code --23226 3. StatelFederal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this xnomination -request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and / meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property xmeets -does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: - natiob - statewide -x local Signature of certifyiirg officialmitle Virginia Department of Historic Resources State or Federal agencylbureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property - meets -does not meet the National Register criteria.