Lost Cause Monuments and Public Controversy Through Bruno Latour and Henri Lefebvre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Follow in Lincoln's Footsteps in Virginia

FOLLOW IN LINCOLN’S FOOTSTEPS IN VIRGINIA A 5 Day tour of Virginia that follows in Lincoln’s footsteps as he traveled through Central Virginia. Day One • Begin your journey at the Winchester-Frederick County Visitor Center housing the Civil War Orientation Center for the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields National Historic District. Become familiar with the onsite interpretations that walk visitors through the stages of the local battles. • Travel to Stonewall Jackson’s Headquarters. Located in a quiet residential area, this Victorian house is where Jackson spent the winter of 1861-62 and planned his famous Valley Campaign. • Enjoy lunch at The Wayside Inn – serving travelers since 1797, meals are served in eight antique filled rooms and feature authentic Colonial favorites. During the Civil War, soldiers from both the North and South frequented the Wayside Inn in search of refuge and friendship. Serving both sides in this devastating conflict, the Inn offered comfort to all who came and thus was spared the ravages of the war, even though Stonewall Jackson’s famous Valley Campaign swept past only a few miles away. • Tour Belle Grove Plantation. Civil War activity here culminated in the Battle of Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864 when Gen. Sheridan’s counterattack ended the Valley Campaign in favor of the Northern forces. The mansion served as Union headquarters. • Continue to Lexington where we’ll overnight and enjoy dinner in a local restaurant. Day Two • Meet our guide in Lexington and tour the Virginia Military Institute (VMI). The VMI Museum presents a history of the Institute and the nation as told through the lives and services of VMI Alumni and faculty. -

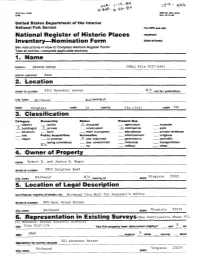

Nomination Form Date Entered See Instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type All Entries-Complete Applicable Sections 1

OM6 No.1024-0018 Erp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory-Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries-complete applicable sections 1. Name hlstortc BRANCH HOUSE (VHLC File 6127-246) -- ----- - - and or common Same 2. Location 8 number 2501 Monument Avenue - N/Anot for publication city, town Richmond Fk4\ vicinity of stale Virginia code 5 1 county (in city) code 750 3.- Classification- - ~~ Category Ownership Status Present Use -district -public X occupied agriculture -museum X building@) X private unoccupied _.X_ commercial - _park -structure -both -work in progress -educational -private residence -site Public Acquisition Accessible -entertainment -.religious -object - in process x yes: restricted -governmani -scientific being considered yes: unrestricted -industrial -transportation TA -no -military -other: 4. Owner of Property name Robert E. and Janice W. Pogue street & number 3902 Sulgrave Ibad Virginia 23221 city, town N/Avicinity of state -- -- 5. Location of Leaal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Richmond City Hall Tax Assessor's Off ice street & number 900 East Broad Street - city, town Richmond state Virginia 23219 6. Representation in Existing $urveys(see continuation Sheet iil) (I) Monument Avenue HlstOrlc ulstrlct titleFile 11127-174 has this properly been determined eligible? -yes -noX - X 1969 -federal slate county .- local date ---- - --.-- 221 Governor Street depository for survey records -- - -. -- - - - Richmond Virginia 23219 state city, town -- . - 7. Description Condition Check one Check one _X excellent -deteriorated & unaltered -L original site -good -ruins -altered -moved date -..-.___--p-N/ A A fair -unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance SUMMARY DESCRIPTION The Branch House at 2501 Monument Avenue is situated on the southeast corner of Monument Avenue and Davis Street in the Fan District of Richmond. -

Human Rights, Collective Memory, and Counter Memory: Unpacking the Meaning of Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia Melanie L

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Art Education Publications Dept. of Art Education 2011 Human Rights, Collective Memory, and Counter Memory: Unpacking the Meaning of Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia Melanie L. Buffington Virginia Commonwealth University, [email protected] Erin Waldner Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/arte_pubs Part of the Art Education Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Social Policy Commons Copyright © 2011 Journal of Cultural Research in Art Education Downloaded from http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/arte_pubs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Dept. of Art Education at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art Education Publications by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Human Rights, Collective Memory,' and Counter Memory: Unpacking the Meaning of Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia M ELANIE L. BUFFI" GTO'l ' ''D ERI" W ALD " ER ABSTRACT Th is article addresses human rights issues of the built environment via the presence of monuments in publi c places. Because of their prominence, monuments and publi c art can offer teachers and students many opportunit ies for interdiscip li nary study that directly relates to the history of their location Through an exploration of the ideas of co llective memory and counter memory, t his articl e explores the spec ific example of Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia, Further; the aut hors investigate differences in t he ways monu ments may be understood at the time they were erected versus how they are understood in the present. -

Confederate Monument REMIX"

Proposal for: Intent to Acquire Civil War Monument AKA: "Confederate Monument REMIX" City of Richmond, VA Richmond City Counsel Notice: Richmond City Council News Release, AuGust 17, 2020 Ord. No. 2020-154 DARNstudio 18 Forest Farm Drive Roxbury, CT 06783 www.DARNstudio.com 917.482.1142 CONFEDERATE MONUMENT REMIX SEPTEMBER 2020 1. LETTER OF INTENT September 8, 2020 Richmond City Council Richmond City Hall 900 E. Broad Street, Suite 305 Richmond, Virginia 23219 USA 804.646.2778 (tel) Attn: RE: Proposal to Acquire Civil War Monument September 8, 2020 Dear Chairperson, We are pleased to present our proposal for the City of Richmond's Civil War Monument DeaccessioninG Request. DARNstudio is a collaboration of artists David Anthone and Ron Norsworthy. Our work investigates the built, designed, or otherwise manifested world we live in, breaks down its components and uncouples them from their implicit and inherited meaninG(s). We then re- assemble in a way that disrupts its original function. Our work encourages alternative ways of understanding objects, ideas and structures through a process we refer to as “re:meaning” ThrouGh reassiGnment, remixinG, inversion, or juxtaposition DARNstudio’s work examines the purpose of things. These things may range from the macro and intangible (cultural institutions and norms) to the micro and concrete (mundane objects, words, expressions or phrases). We glean new meanings from these things in their disrupted reconfigurations which triggers new dialogue on the commonplace, the happenstance, and the “extraordinary ordinary”. Our Goal is to cast the familiar in an unexpected context so that it can be seen in an unfamiliar and new way. -

Monument Avenue Historic District Richmond, Virginia ______Aerial View of Monument Ave

18 JuM south (left) of Monument Avenue, Park Avenue traces the htstonc path at the IP,*; ihe old Sydney grid (nou the Fan District) from the avenue precinct Virginia Si.tte ! Monument Avenue Historic District Richmond, Virginia ____________ Aerial view of Monument Ave. looking west ——————————————————— Photo: Sarah Driggs, June 1997 ————— Monument Avenue Historic District I Richmond, Virginia Aerial view of Monument Ave. looking west Photo: Sarah Driggs, June 1997 -k - !1 i ' ' . > •>* n , t \ • '• i; i " • i 1 ,. • i i •• ' i k , 1 kl 1 *• t •* j Uj i ~a K • it «• ' t:i' - : : t ,r.*• "' tf ' "ii ~"'~"m*•> » *j -. '.— 1. .1 - "r r. A ""~«"H "i •«• i' "j —— „ T~ . ~_ ———."•".' ^f T. i_J- Y 22 Somewhat idealized plal of the AJIen Addition, 1888, two ycare before the Monument Avenue Historic District Richmond, Virginia Lee Monument & 1800 Monument Ave., The JefFress House looking northwest Photo: Sarah Driees, June 1997 IT* Monument Avenue Historic District Richmond, Virginia 2314, 2320, & 2324 Monument Ave. looking west Photo: Sarah Driggs, June 1997 ——49Ktta£E£i Monument Avenue Historic District Richmond, Virginia 2200 & 2204 Monument Ave., porches looking west Photo: Sarah Driggs, June 1997 ,, f-ftf? Monument Avenue Historic District Richmond, Virginia Stuart Monument looking northwest Photo: Sarah Driggs, June 1997 Monument Avenue Historic District Richmond, Virginia Stonewall Jackson Monument & 622 North Boulevard looking southwest Photo: Sarah Driees, June 1997 Monument Avenue Historic District Richmond, Virginia Matthew Fontaine Maury Monument & 3101 Monument Ave., the Lord Fairfax Apartments Photo: Sarah Driggs, June 1997 !?*-sf* • •«.« r*x. • • V- ^-SK. ^*-'VlBr v» Monument Avenue Historic District I Richmond, VA Arthur Ashe Monument Photo: Sarah Prises. -

St.Catherine's

fall 2008 vol. 67 no. 1 st.catherine’snow inside: The Essence of St. Catherine’s Spirit Fest Highlights Alumnae and Parent Authors 1 Blair Beebe Smith ’83 came to St. Catherine’s from Chicago as a 15-year-old boarding student with a legacy connection - her mother, Caroline Short Beebe ’55 - and the knowledge that her great-grand- father had relatives in town. “I didn’t know a soul,” said Blair, today a Richmond resident and kitchen designer with Heritage Woodworks. A younger sister – Anne Beebe ’85 – shortly followed her to St. Catherine’s, and today Blair maintains a connection with her alma mater through her own daughters – junior Sarah and freshman Blair Beebe Smith ’83 Peyton. Her son Harvard is a 6th grader at St. Christopher’s. Blair recently shared her memories of living for two years on Bacot II: Boarding Memories2 The Skirt Requirement “Because we had to Williams Hotel “We had our permission slips signed wear skirts to dinner, we threw on whatever we could find. and ready to go for overnights at Sarah Williams’ house. It didn’t matter if it was clean or dirty, whether it matched Sarah regularly had 2, 3, 4 or more of us at the ‘Williams the rest of our outfit or not…the uglier, the better.” Hotel.’ It was great.” Doing Laundry “I learned from my friends how Dorm Supervisors “Most of our dorm supervi- to do laundry (in the basement of Bacot). I threw every- sors were pretty nice. I was great friends with Damon thing in at once, and as a result my jeans turned all my Herkness and Kim Cobbs.” white turtlenecks blue. -

Save Outdoor Sculpture!

Save Outdoor Sculpture! . A Survey of Sculpture in Vtrginia Compiled by Sarah Shields Driggs with John L. Orrock J ' Save Outdoor Sculpture! A Survey of Sculpture in Virginia Compiled by Sarah Shields Driggs with John L. Orrock SAVE OUTDOOR SCULPTURE Table of Contents Virginia Save Outdoor Sculpture! by Sarah Shields Driggs . I Confederate Monuments by Gaines M Foster . 3 An Embarrassment of Riches: Virginia's Sculpture by Richard Guy Wilson . 5 Why Adopt A Monument? by Richard K Kneipper . 7 List of Sculpture in Vrrginia . 9 List ofVolunteers . 35 Copyright Vuginia Department of Historic Resources Richmond, Vrrginia 1996 Save Outdoor Sculpture!, was designed and SOS! is a project of the National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, and the National prepared for publication by Grace Ng Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Property. SOS! is supported by major contributions from Office of Graphic Communications the Pew Charitable Trusts, the Getty Grant Program and the Henry Luce Foundation. Additional assis Virginia Department of General Services tance has been provided by the National Endowment for the Arts, Ogilvy Adams & Rinehart, Inc., TimeWarner Inc., the Contributing Membership of the Smithsonian National Associates Program and Cover illustration: ''Ligne Indeterminee'~ Norfolk. Members of its Board, as well as many other concerned individuals. (Photo by David Ha=rd) items like lawn ornaments or commercial signs, formed around the state, but more are needed. and museum collections, since curators would be By the fall of 1995, survey reports were Virginia SOS! expected to survey their own holdings. pouring in, and the results were engrossing. Not The definition was thoroughly analyzed at only were our tastes and priorities as a Common by Sarah Shields Driggs the workshops, but gradually the DHR staff wealth being examined, but each individual sur reached the conclusion that it was best to allow veyor's forms were telling us what they had dis~ volunteers to survey whatever caught their eye. -

Righting History: Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia

Public History Review Righting History: Vol. 28, 2021 Monument Avenue, Richmond, Virginia Paul Kiem DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/phrj.v28i0.7786 Despite the widely accepted view that only victors get to write history, commemoration of the losing Confederate cause has been far more widespread in the United States than Union commemoration. While there may have been only a limited long- term impact on the writing of scholarly history, Confederate commemoration has been able to impose its often heavily sanitised Southern heroes and dubious history – that the ‘lost cause’ was about defending states’ rights – on many public spaces. This commemoration has taken many forms, including the erection of statues, the placement of plaques and the naming of schools, military bases and public buildings.1 © 2021 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article Confederate commemoration has always been contested. Black American politicians, who distributed under the terms had been elected to the post- Civil War Virginia legislature prior to black disenfranchisement of the Creative Commons at the start of the twentieth century, spoke out against the first efforts at Confederate Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https:// commemoration. As early as 1871, Senator Frank Moss objected to a proposal to display a creativecommons.org/licenses/ portrait of General Robert E. Lee in the state Capitol. ‘Gen. Lee had fought to keep him in by/4.0/), allowing third parties slavery’, Moss reasoned, ‘he couldn’t vote to put his picture on these walls.’2 In 1890, when to copy and redistribute the Confederate commemoration in Richmond began in earnest with the erection of a statue material in any medium or format and to remix, to Lee on Monument Avenue, black newspaper editor John Mitchell Jr was prescient in his transform, and build upon the understanding of the deeper ramifications: ‘The South may revere the memory of its chieftains. -

Tributes to the Past, Present, and Future: Confederate Memorialization in Virginia, 1914-1919 Thomas R. Seabrook Thesis Submitte

Tributes to the Past, Present, and Future: Confederate Memorialization in Virginia, 1914-1919 Thomas R. Seabrook Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History Paul D. Quigley, Chair Kathleen W. Jones David P. Cline 30 April 2015 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Confederacy; Monuments; Memorials; Memorialization; Virginia; 1910s; Civil War; World War I Copyright 2015 by Thomas R. Seabrook Tributes to the Past, Present, and Future: Confederate Memorialization in Virginia, 1914-1919 Thomas R. Seabrook ABSTRACT Between 1914 and 1919, elite white people erected monuments across Virginia, permanently transforming the landscape of their communities with memorials to the Confederacy. Why did these Confederate memorialists continue to build monuments to a conflict their side had lost half a century earlier? This thesis examines this question to extend the study of the Lost Cause past the traditional stopping date of the Civil War semicentennial in 1915 and to add to the study of memorialization as a historical process. Studying the design and language of monuments as well as dedication orations and newspaper coverage of unveiling ceremonies, this thesis focuses on Virginia’s Confederate memorials to provide a case study for the whole South. Memorialization is always an act of the present as much as an honoring of the past. Elite white Virginians built memorials to speak to their contemporaries at the same time they claimed to speak for them. Memorialists turned to the Confederacy for support in an effort to maintain their status at the top of post-Reconstruction Southern society. -

Arthur Ashe and Monument Avenue

Arthur Ashe and Monument Avenue Andy Perez UNIV 112 MWF11:00 Background ❖ Richmond’s Monument Avenue runs from the west end of the city to The Fan neighborhood, near the main campus of Virginia Commonwealth University ❖ Largely known for the 6 monuments that exist on its pavement ➢ 4 of those are commemorated to Confederate leaders during the American Civil War, including CSA President Jefferson Davis and General Robert E. Lee The Arthur Ashe Monument ❖ Located on the intersection of Monument Avenue and Roseneath Road ❖ Sculpted by Paul DiPasquale ❖ Was unveiled in 1996 Cross Hatching: Location ❖ When the Ashe monument location was determined through a council meeting, Richmond residents voiced their displeasure with the council’s decision ❖ People that do not know Richmond’s history and culture like the city’s residents would not understand the controversy of placing the Ashe Monument on Monument Avenue ❖ Richmond residents see the Ashe monument as misplaced: ➢ Some believe that the monument breaks the continuity of Confederate statues on the avenue; considering that Arthur Ashe was African American and the men being commemorated were from a place that promoted slavery and white supremacy ➢ Others see the monument at the Arthur Ashe Athletic Center, like how some stadiums have statues of notable past players Differences in Design ❖ In comparing the design of the Arthur Ashe Monument and the other monuments, there are some obvious contrasts: ➢ Size ➢ Style of Monument Cross Hatching: Differences in Design ❖ A main gripe that residents have when comparing the Ashe Monument to the Confederate memorials is the size comparison. ➢ One side sees the fact that a successful colored man who was a prominent figure in the education of HIV/AIDS has a smaller monument than a couple of men that represent inhumane; so someone like Ashe has to have a monument that better represents the grand importance of Ashe’s life and humanitarian work. -

Architectural Reconnaissance Survey, GNSA, SAAM, and BBHW

ARCHITECTURAL RECONNAISSANCE Rͳ11 SURVEY, GNSA, SAAM, AND BBHW SEGMENTS ΈSEGMENTS 15, 16, AND 20Ή D.C. TO RICHMOND SOUTHEAST HIGH SPEED RAIL October 2016 Architectural Reconnaissance Survey for the Washington, D.C. to Richmond, Virginia High Speed Rail Project Greendale to SAY/WAY (GNSA), SAY/WAY to AM Jct (SAAM) and Buckingham Branch/Hospital Wye (BBHW) Segments, Henrico County and City of Richmond Architectural Reconnaissance Survey for the Washington, D.C. to Richmond, Virginia High Speed Rail Project Greendale to SAY/WAY (GNSA), SAY/WAY to AM Jct (SAAM) and Buckingham Branch/Hospital Wye (BBHW) Segments, Henrico County and City of Richmond by Caitlin C. Sylvester and Heather D. Staton Prepared for Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation 600 E. Main Street, Suite 2102 Richmond, Virginia 23219 Prepared by DC2RVA Project Team 801 E. Main Street, Suite 1000 Richmond, Virginia 23219 October 2016 October 24, 2016 Kerri S. Barile, Principal Investigator Date ABSTRACT Dovetail Cultural Resource Group (Dovetail), on behalf of the Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT), conducted a reconnaissance-level architectural survey of the Greendale to SAY/WAY (GNSA), SAY/WAY to AM Jct (SAAM) and Buckingham Branch/ Hospital Wye (BBHW) segments of the Washington, D.C. to Richmond Southeast High Speed Rail (DC2RVA) project. The proposed Project is being completed under the auspices of the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) in conjunction with DRPT. Because of FRA’s involvement, the undertaking is required to comply with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended. -

Thanks for the Memories: Former FDA Presidents Recall Highlights of Their Administrations Part Three: the Eighties by Gail Zwirner, FDA Historian

Thanks for the Memories: Former FDA Presidents Recall Highlights of Their Administrations Part Three: The Eighties By Gail Zwirner, FDA Historian James Stutts (1980‐81) began his presidency after completing a term as Zoning Committee Chair. In an interview Drew Carneal did with him for the November 1979 Fanfare, he said while he felt “overcrowding, excessive traffic and inappropriate commercial uses can quickly deteriorate any neighborhood, zoning policy must remain flexible to encourage the healthy diversity which gives the Fan its distinctive personality.” Zoning review has been and continues to be a primary responsibility of the FDA. City Council finally addressed the issue of returning to two‐way traffic on West Grace Street on May 12, 1980 and the ordinance passed successfully after years of strategizing over this important residential change. The change was scheduled for New Year’s Eve, but was postponed until March 18, 1981. The April 1981 Fanfare reported contagious excitement generated by the change – homes being spruced up and “sold signs replacing sale signs.” A well‐represented Fan contingent appeared before Council again in December 1980 to support a proposed ordinance that would have restricted the number of licensed adult homes in residential districts. The FDA felt that in any district there needs to be a sense of balance, proportion and scale for diverse uses, and the Fan District, most notably West Grace Street, had borne more than its equitable share of such establishments. The proposed ordinance was defeated. The FDA gained tax‐exempt status in 1980. “Being President of the Fan District Association was one of my life’s supreme accomplishments,” says Robert “Bob” Taylor (1981‐82), who now resides in Waynesville, NC.